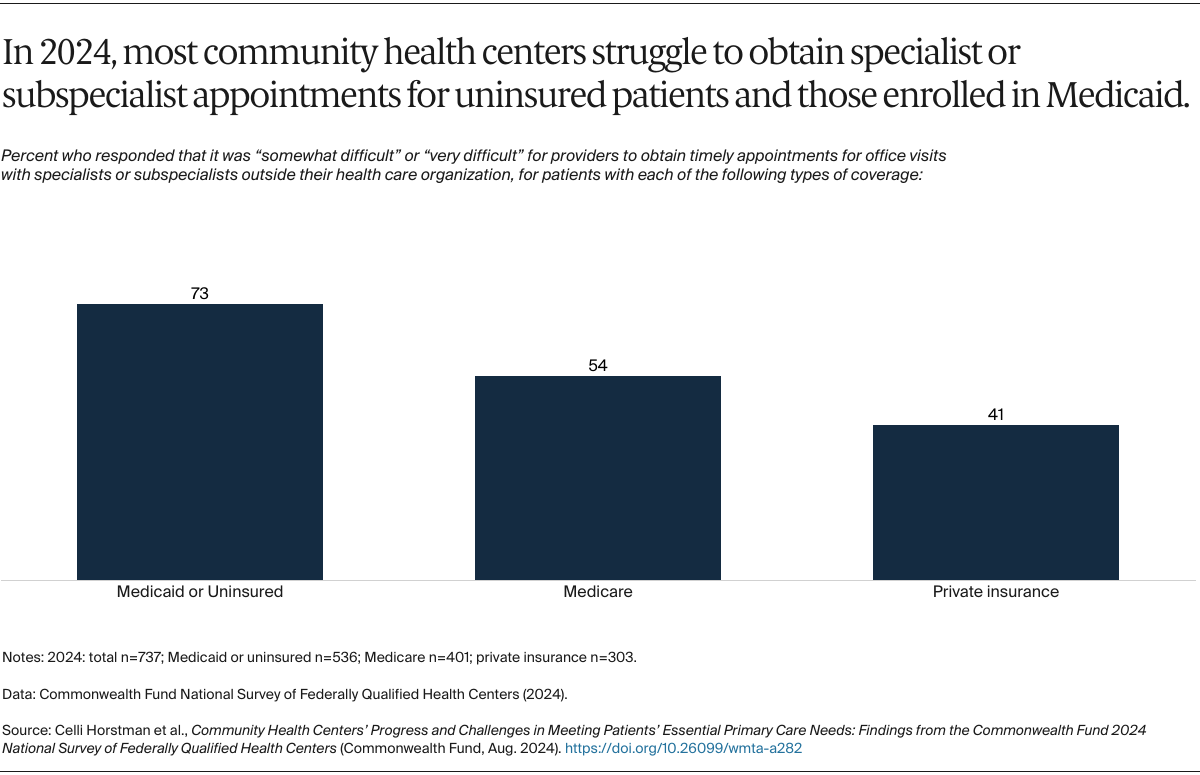

While community health centers accept all patients regardless of their insurance, the same is not true of specialists outside health centers. The majority of CHCs reported difficulty getting timely specialist appointments for their Medicaid patients or those without insurance, more so than for Medicare or privately insured patients. This aligns with other research showing fewer specialists accept Medicaid compared to Medicare or private insurance.26

eConsults, a coordination tool where providers receive advice to inform patient care from specialists without the specialist having to see the patient, may be a solution. However, only 20 percent of CHCs in 2024 reported that they usually or often use eConsults to connect with specialists (data not shown), indicating gaps in access to specialty services.

Discussion

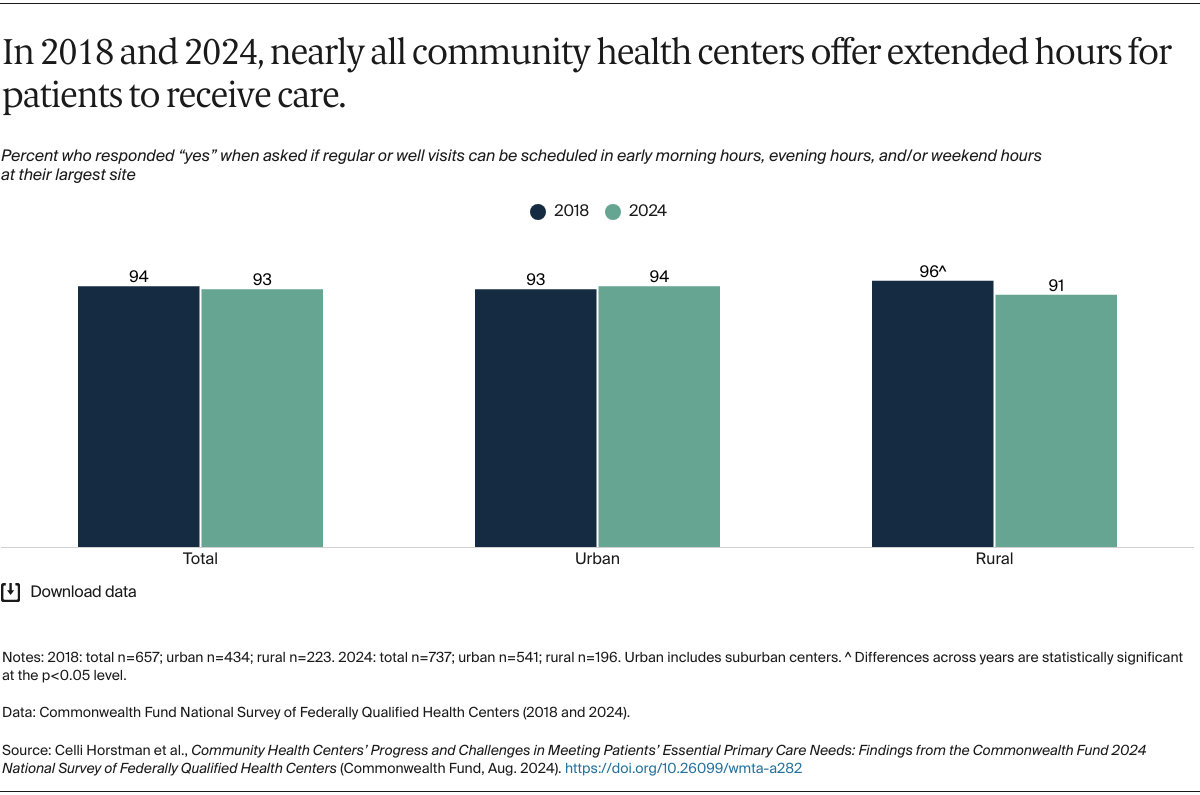

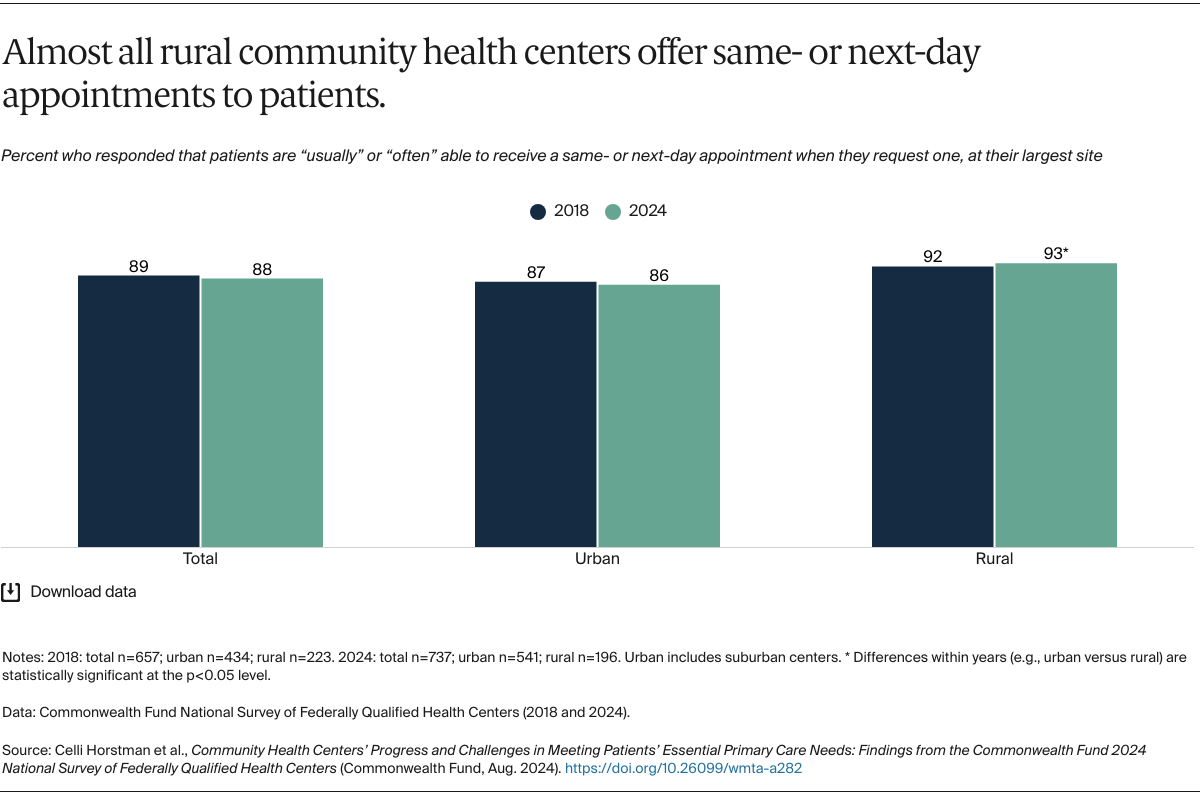

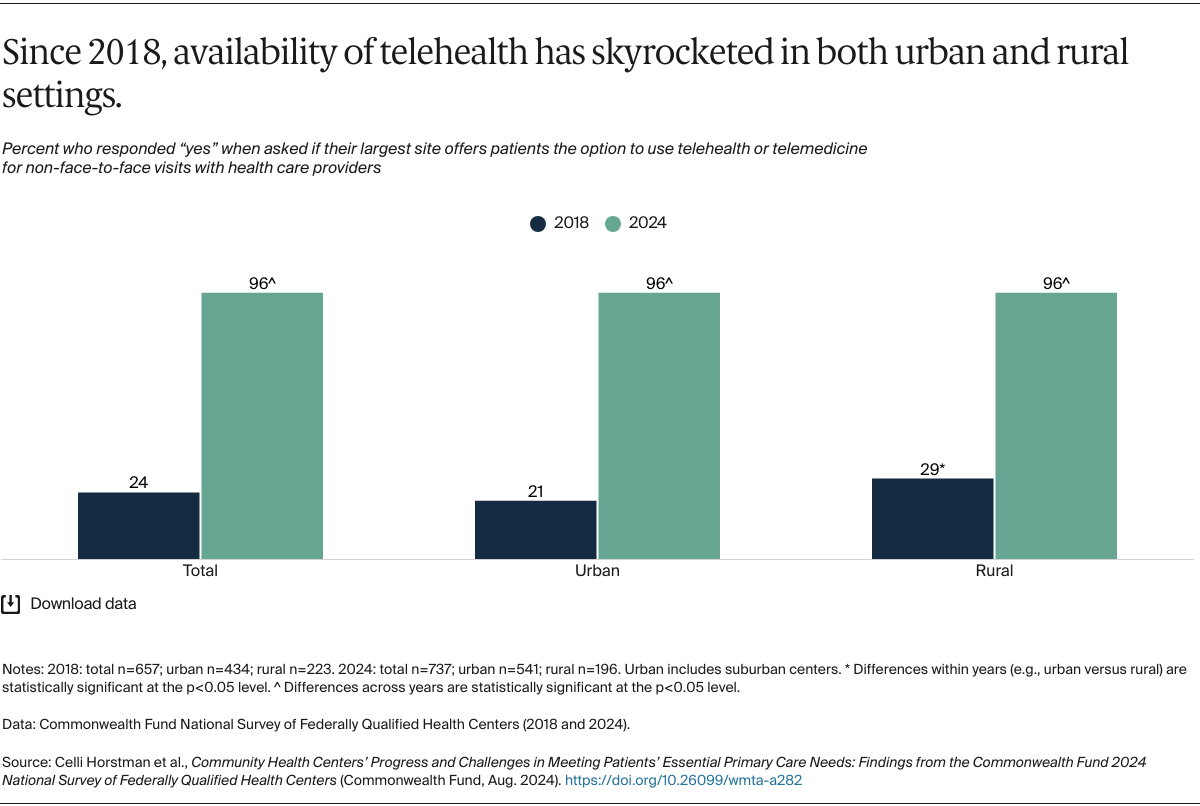

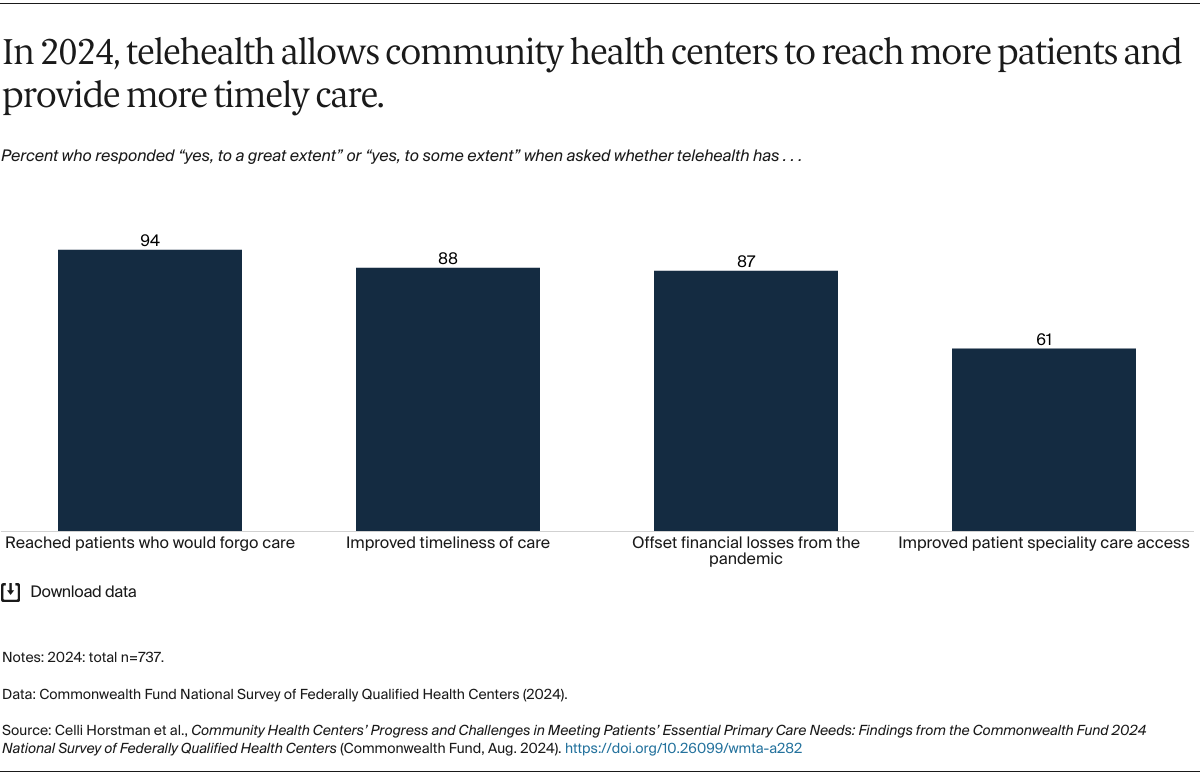

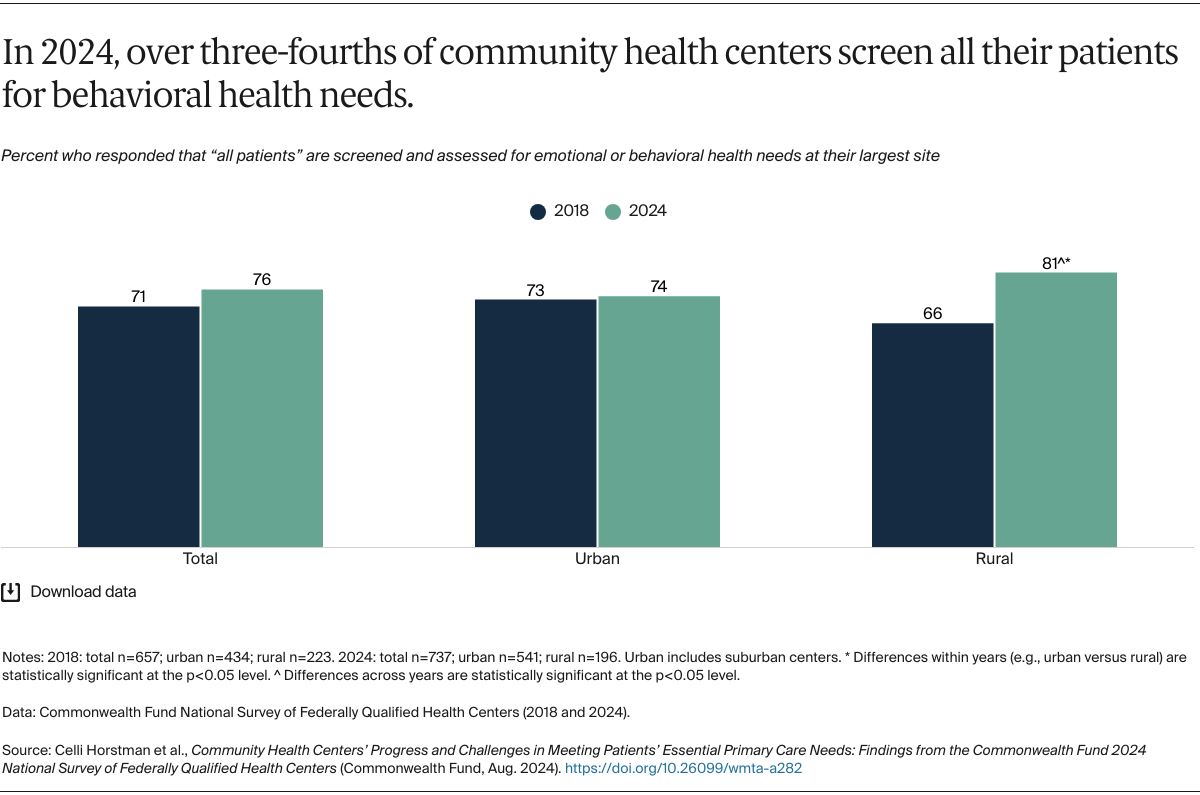

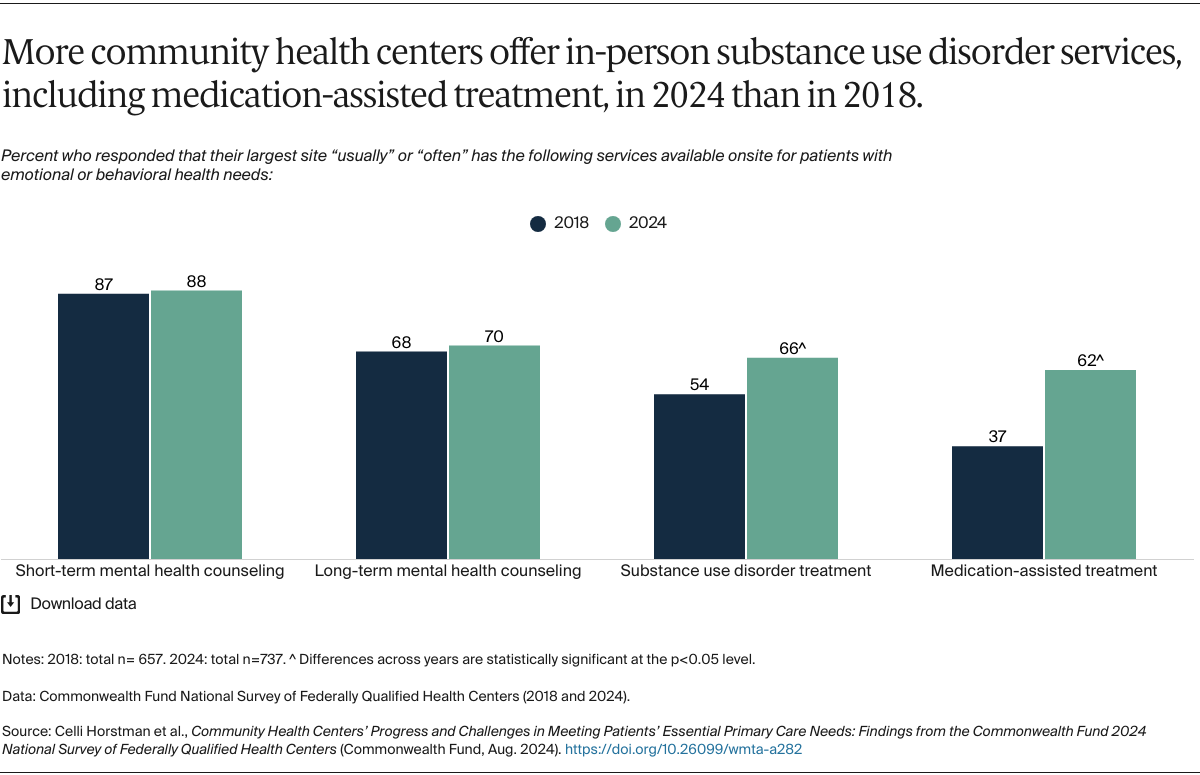

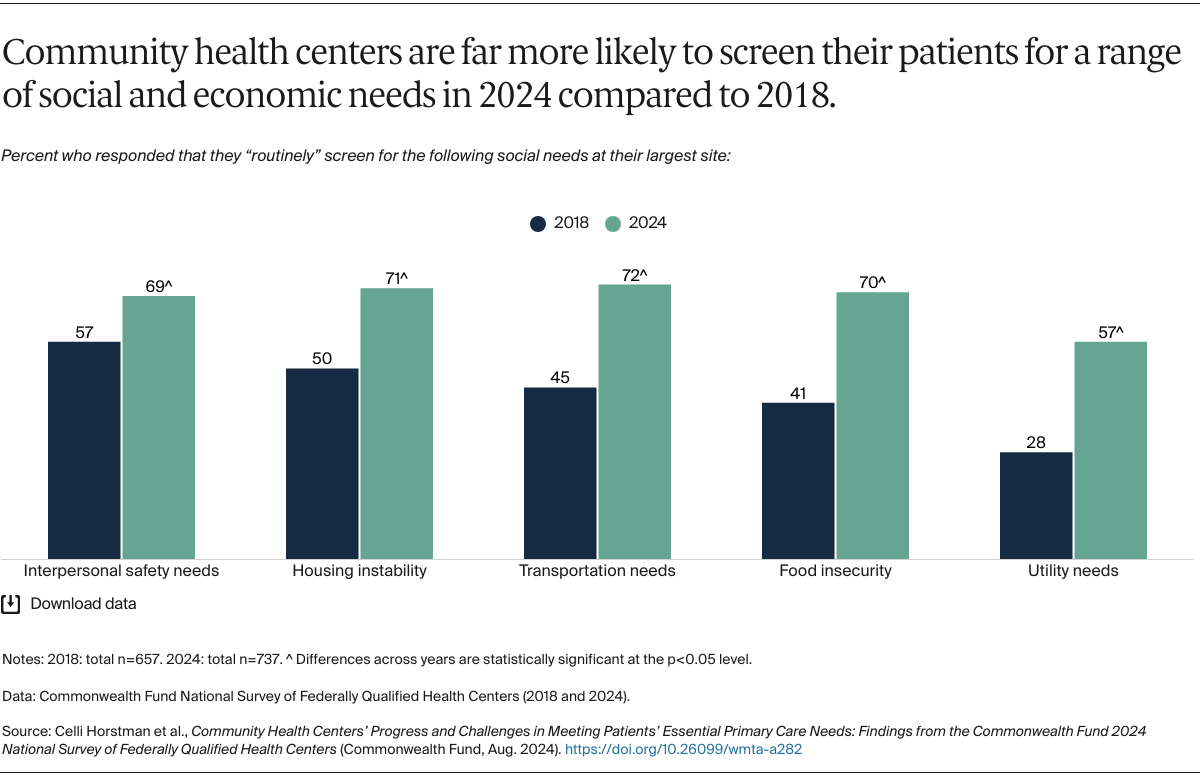

Our findings demonstrate that amid several major public health challenges — from COVID-19 to the behavioral health crisis — community health centers are continuing to provide millions of patients with accessible, comprehensive, and coordinated health care.27 Since 2018, CHCs have maintained timely access to care for their patients, with nearly all consistently offering expanded hours and same- or next-day appointments, accompanied by a substantial rise in telehealth services. They also have made strides in making care more comprehensive for their patients by offering behavioral health services, particularly treatment for substance use disorders, and screening patients for social needs.

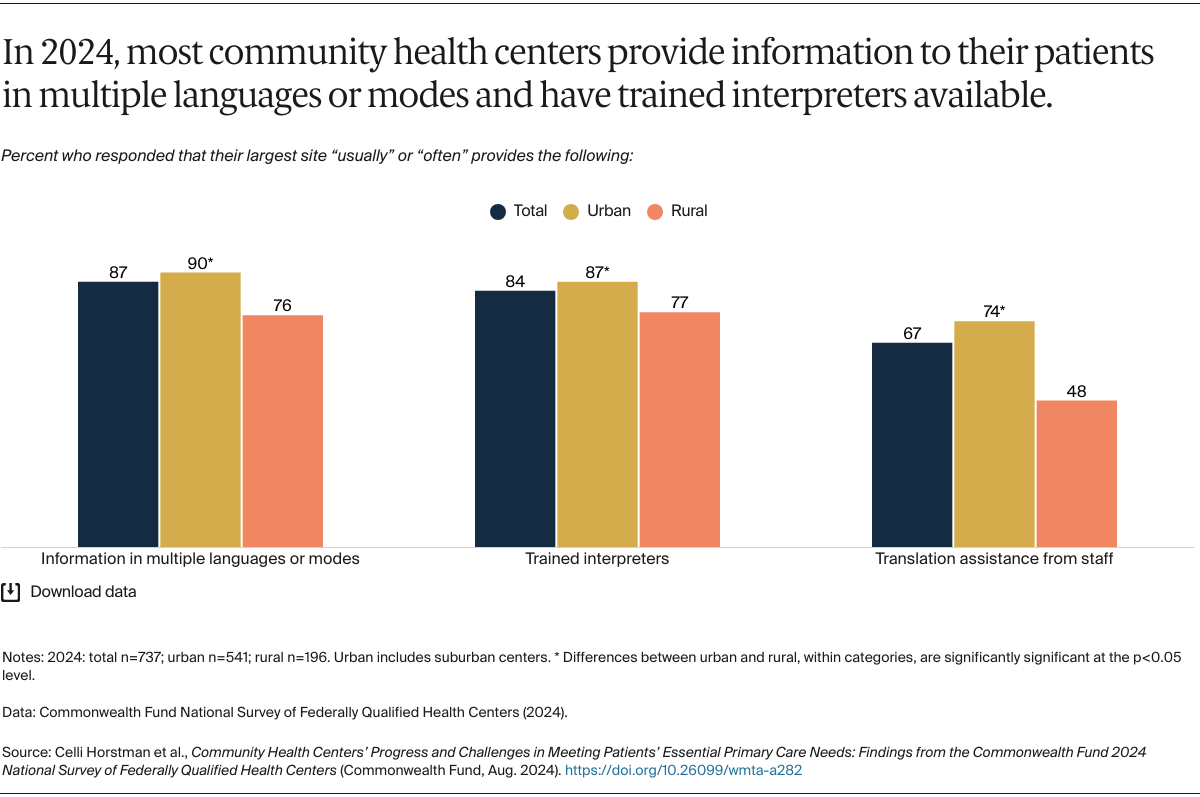

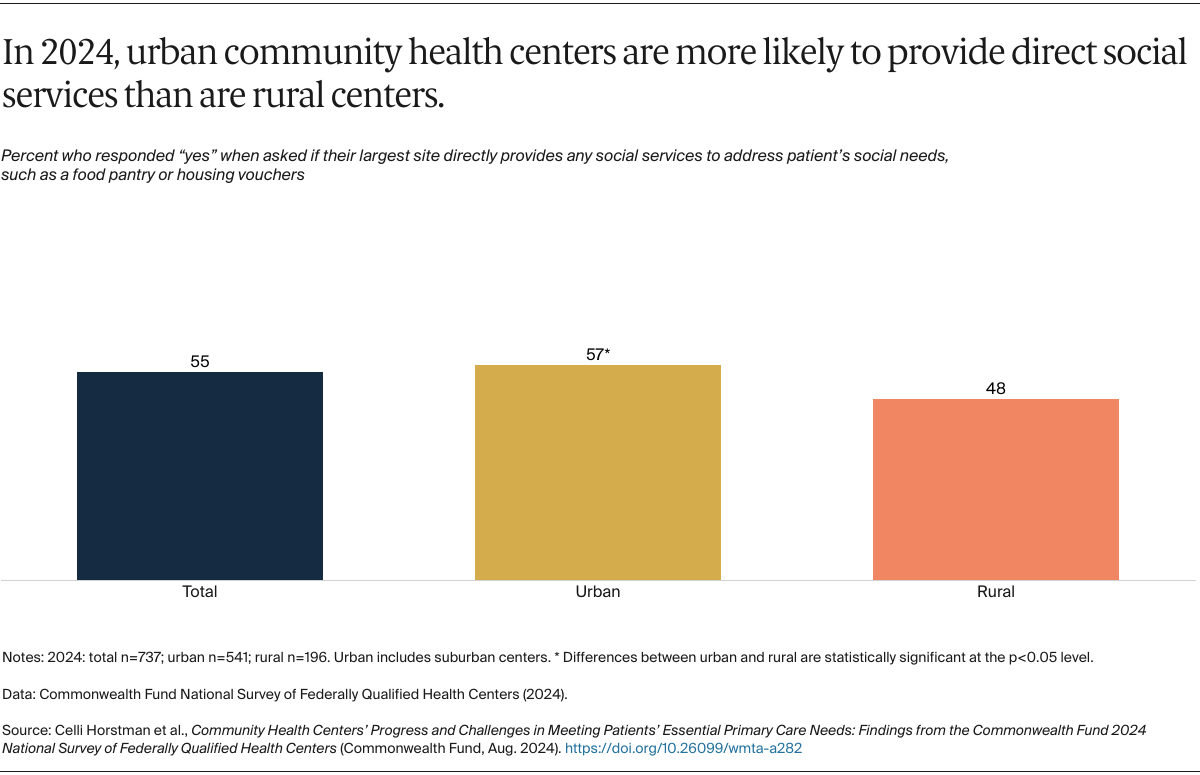

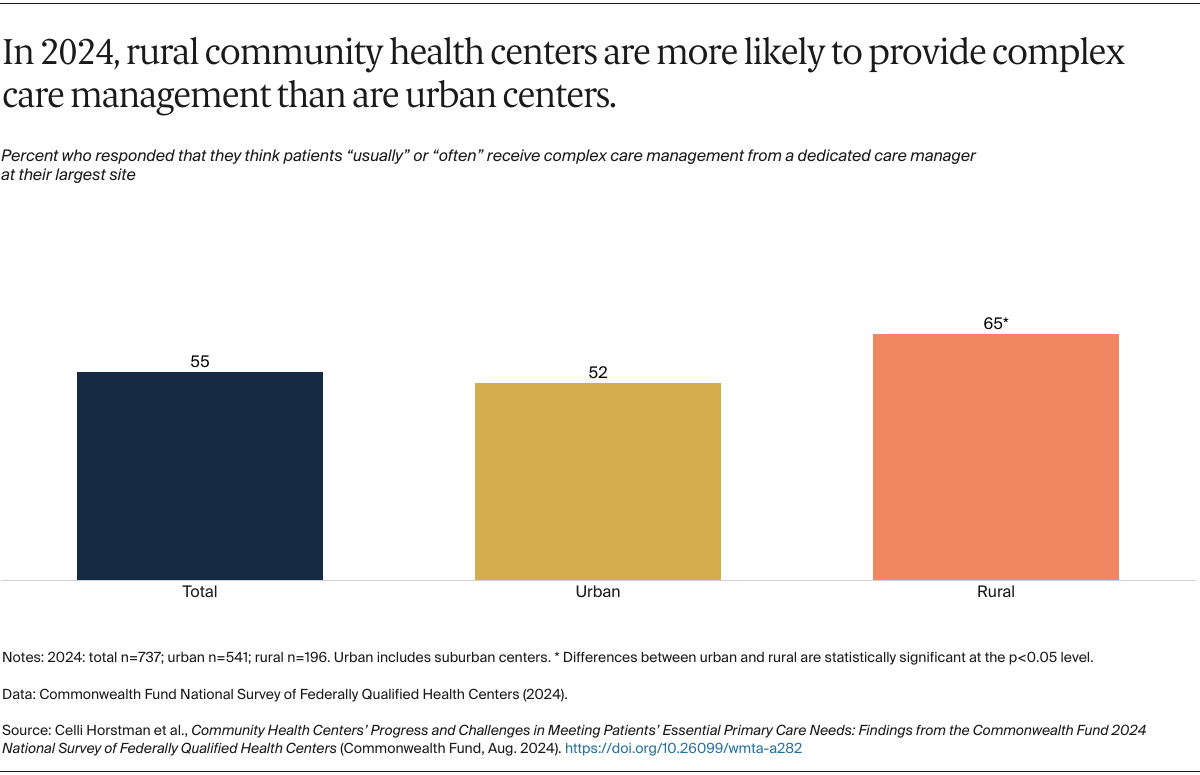

We found some differences between urban and rural community health centers. Urban CHCs were more likely to offer direct social services and translation assistance, while rural CHCs reported higher rates of same- or next-day appointments, behavioral health screening, and complex care management — although overall health centers reported high rates of offering these services regardless of geography. These differences could reflect CHCs adapting to the needs of their unique patient populations or differing financial and staffing capacities in rural and urban settings.

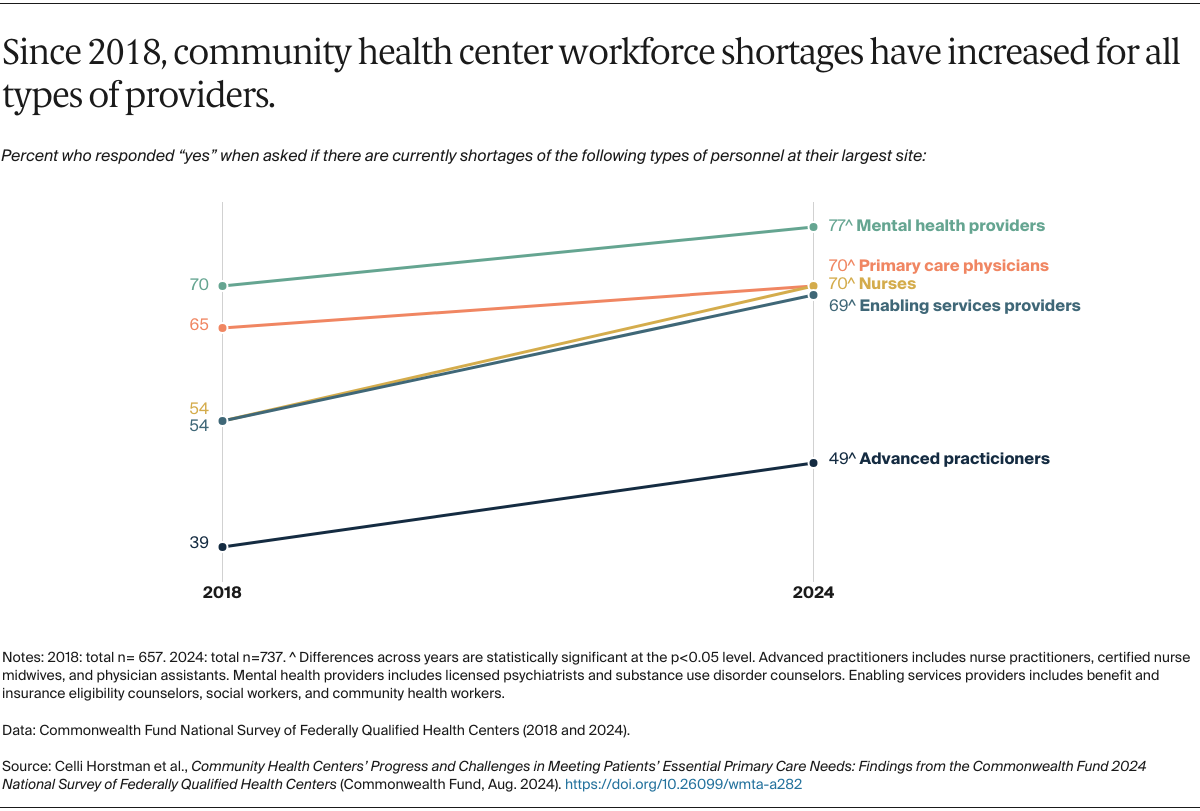

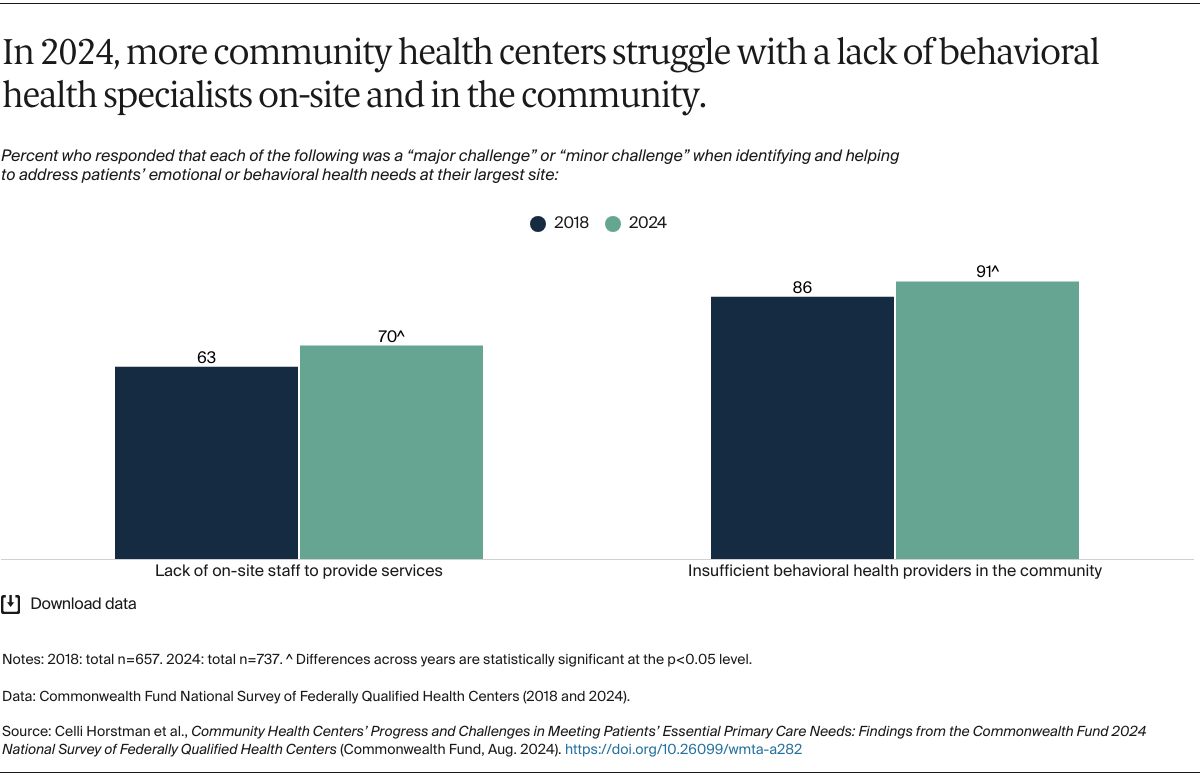

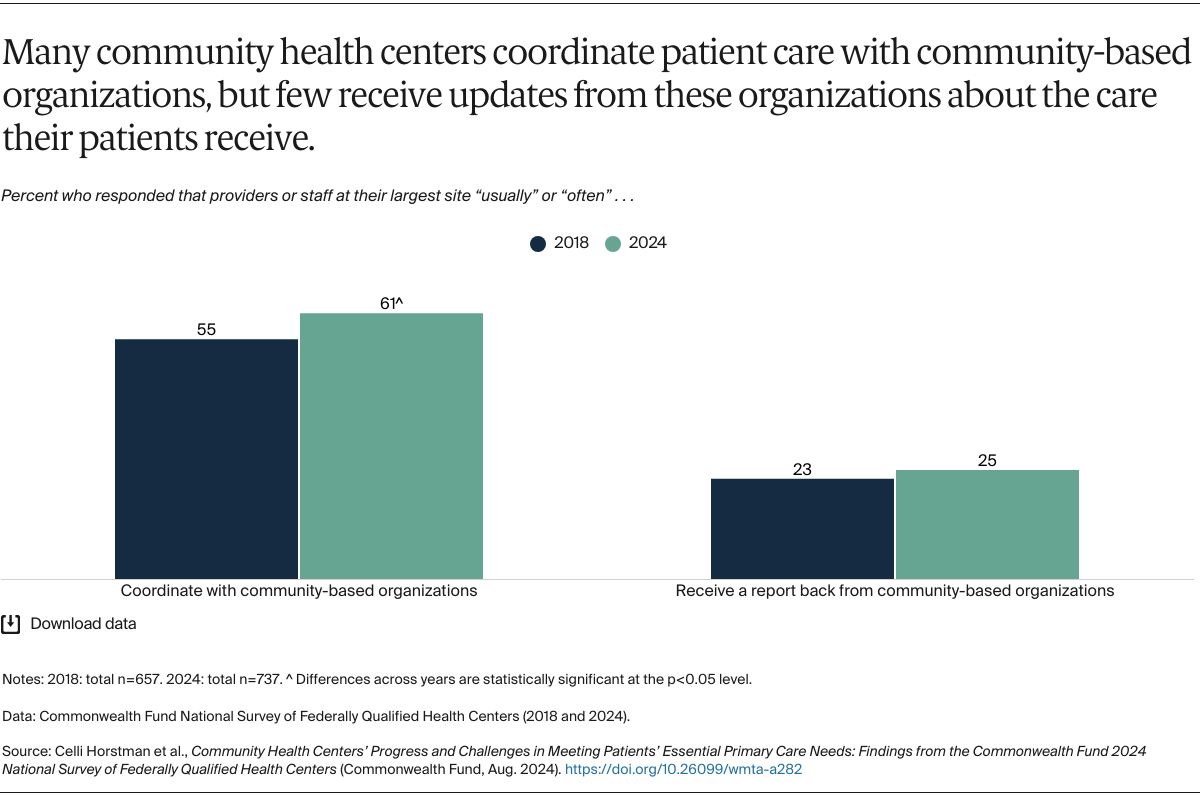

Despite their progress, community health centers are facing challenges that threaten their ability to continue offering high-quality care. They are increasingly reporting shortages across their workforce, and they struggle to coordinate with off-site specialists, behavioral health care, and community-based organizations.

These challenges could be exacerbated in the future, as community health centers already operate on thin financial margins due to their reliance on low Medicaid reimbursements and federal funds that have not kept up with inflation or the increased number of health centers.28 Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and Medicaid eligibility redeterminations will likely continue to stress their finances.29

Policymakers can take several steps to maintain improvements among community health centers and address remaining challenges:

- Reauthorize and expand the Community Health Center Fund. The Community Health Center Fund, a key source of federal funding, is periodically reauthorized by Congress and is currently slated to expire at the end of 2024. Congress can alleviate the funding uncertainty that CHCs are facing by reauthorizing multiyear funding for the program and increasing the amount of funding to keep up with inflation.30 A recent report by the Congressional Budget Office found that increases in CHC funding, which Congress is considering, would yield savings by lowering Medicare and Medicaid expenditures through reductions in high-cost utilization like hospitalizations.31

- Grow the community health center workforce. To address the growing workforce shortages experienced by CHCs, Congress can expand recruitment, retention, and training programs that encourage providers to practice in medically underserved or rural areas, such as the National Health Service Corps and the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education Program.32

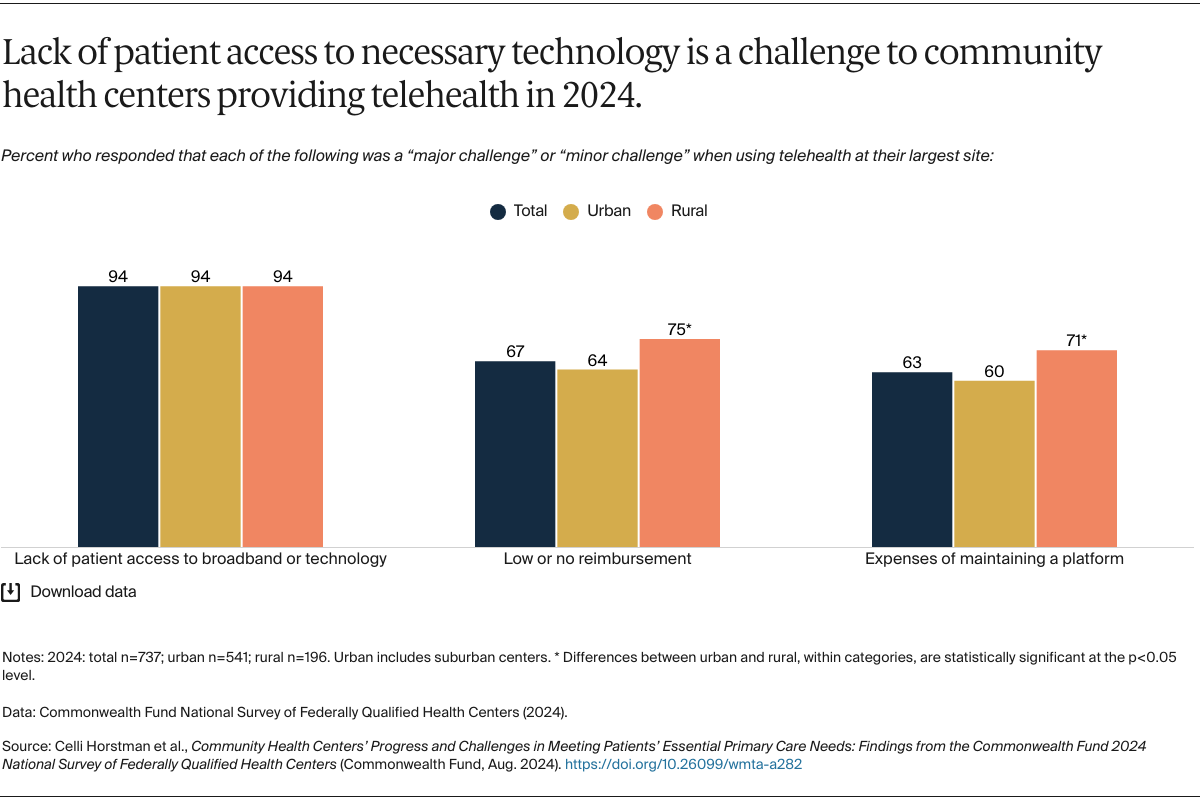

- Support the provision of telehealth. Given the reported benefits of telehealth for patients’ access to care and CHC finances, Congress can take steps to ensure CHCs have sufficient resources to continue offering telehealth, including by aligning telehealth reimbursement more closely with reimbursement for in-person care. Financial assistance could be targeted to rural community health centers, which reported financial challenges to offering telehealth at higher rates, and where telehealth could be critical for ensuring access to care. Congress also could extend federal flexibilities that enabled CHCs to implement and expand telehealth use during the pandemic, such as increased payment rates, which are set to expire at the end of 2024.

- Engage community health centers in payment reform. Beyond grant funding, policymakers can support CHCs’ engagement in value-based payment models, which offer more predictable, flexible funding and reward the provision of high-quality, comprehensive care.33 Models could be designed to intentionally encourage and enable coordination between CHCs and specialists or other providers outside the CHC, which we found was a key gap. To ensure that CHCs engaging in value-based payment are successful, policymakers can offer upfront funding and technical assistance to support their transition.34