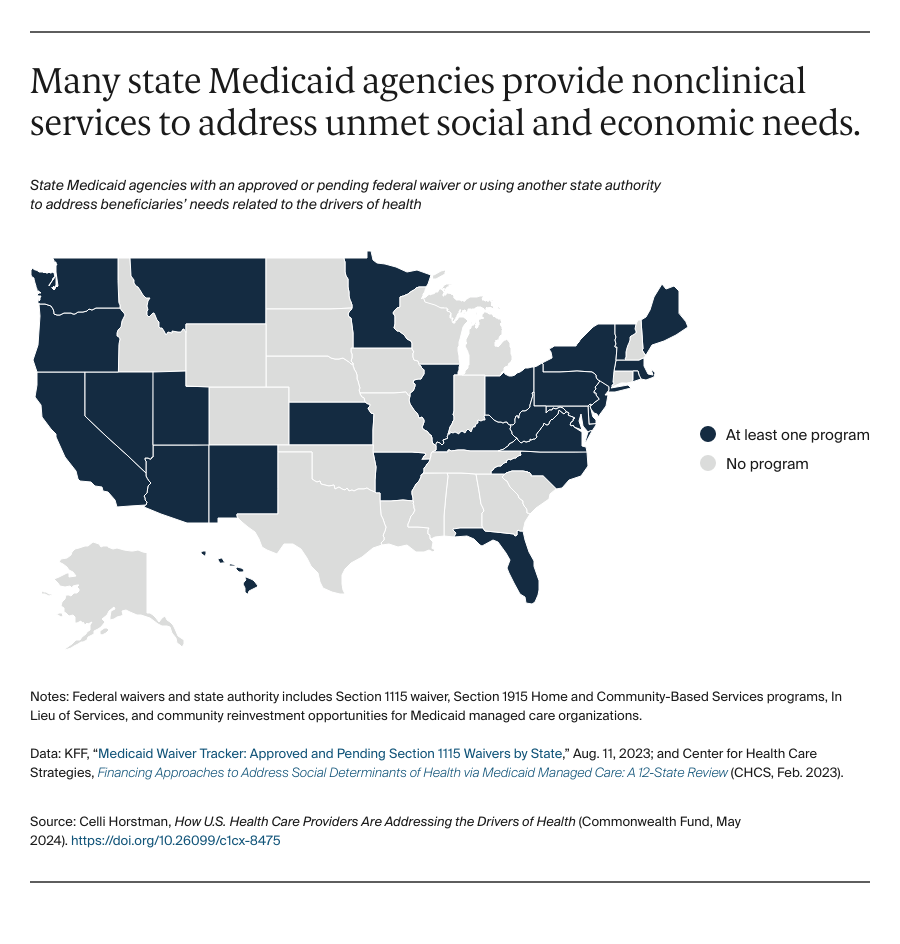

CMS has created state pathways for addressing drivers of health-related needs, which offer a learning opportunity for other payers on how to address the drivers of health. In addition to regulatory efforts to support addressing social needs in Medicare, CMS has created several avenues to provide nonclinical but medically appropriate services to Medicaid beneficiaries, including through home and community-based service (HCBS) programs for older adults and patients with disabilities, Section 1115 waivers that allow states to use federal funds to develop targeted initiatives, and “in lieu of services” that allow managed care plans to address needs through Medicaid benefits. Over half of state Medicaid programs are engaged in such programs.

Minnesota’s HCBS program offers housing stabilization and transition services for older adults and those with disabilities to access reliable, stable housing.13 Through their 1115 waivers, North Carolina offers enhanced case management and nonclinical services, like housing modifications and transportation vouchers via community partners, and Massachusetts provides nutrition counseling and medically tailored meals.14 California has 14 in-lieu-of services, including housing modifications, housing deposits, and medically tailored meals.15

Beyond these efforts targeting individual patient needs, several Medicaid programs are investing in their communities. In Arizona, Medicaid managed care organizations are required to invest 6 percent of their profits into communities, while California and Ohio are planning to implement similar requirements in the future.16

Discussion

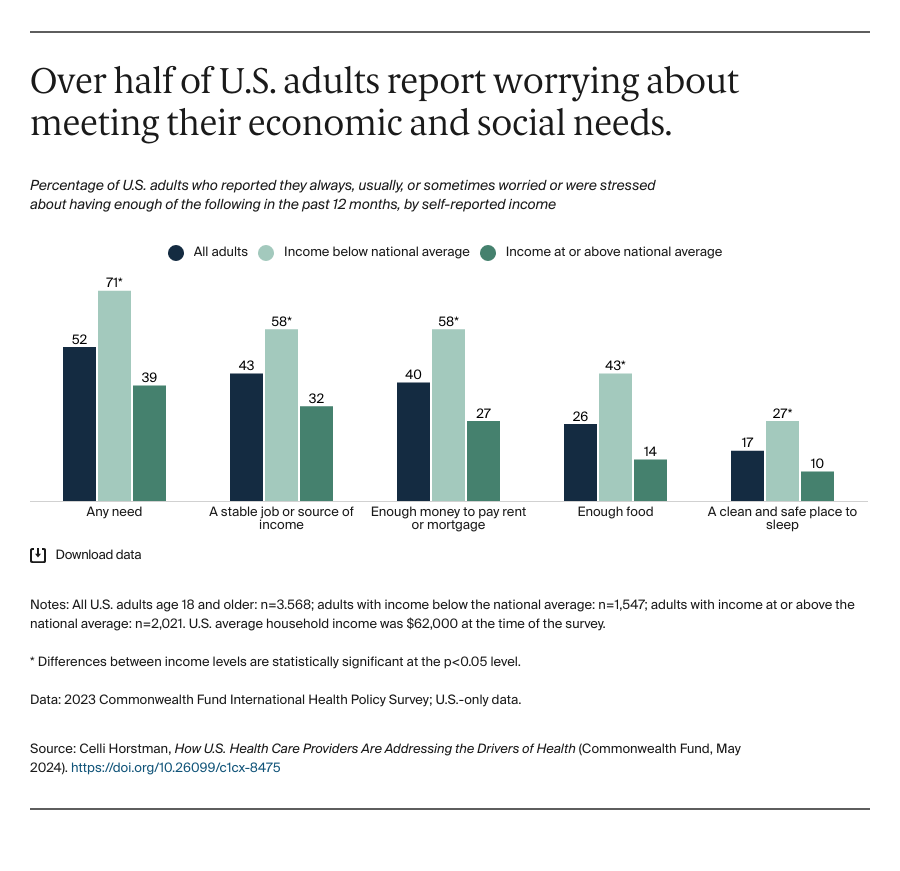

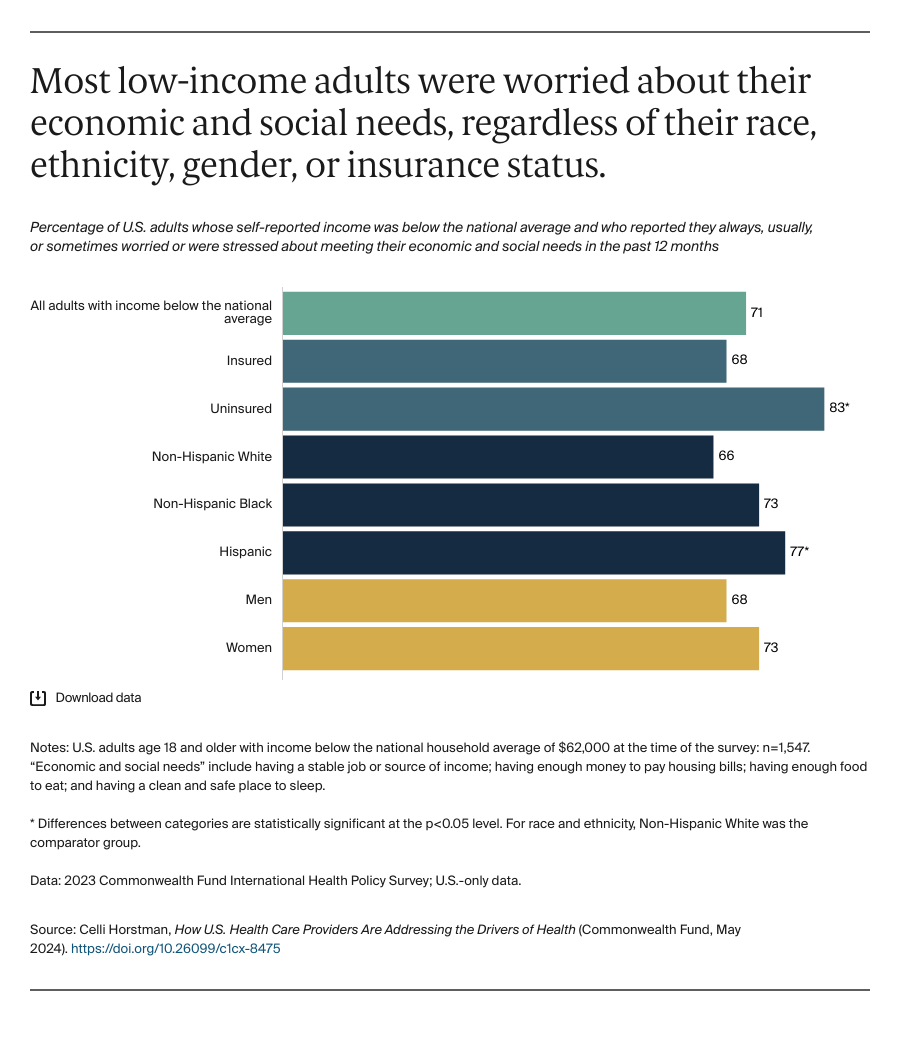

Our survey data revealed that many U.S. adults, especially people with lower incomes and those who are uninsured, are regularly concerned about meeting their social and economic needs, something research shows significantly affects our health and well-being. Evidence suggests that if left unaddressed, these drivers of health can cause new health problems to develop, complicate existing health conditions, and undermine access to care.17

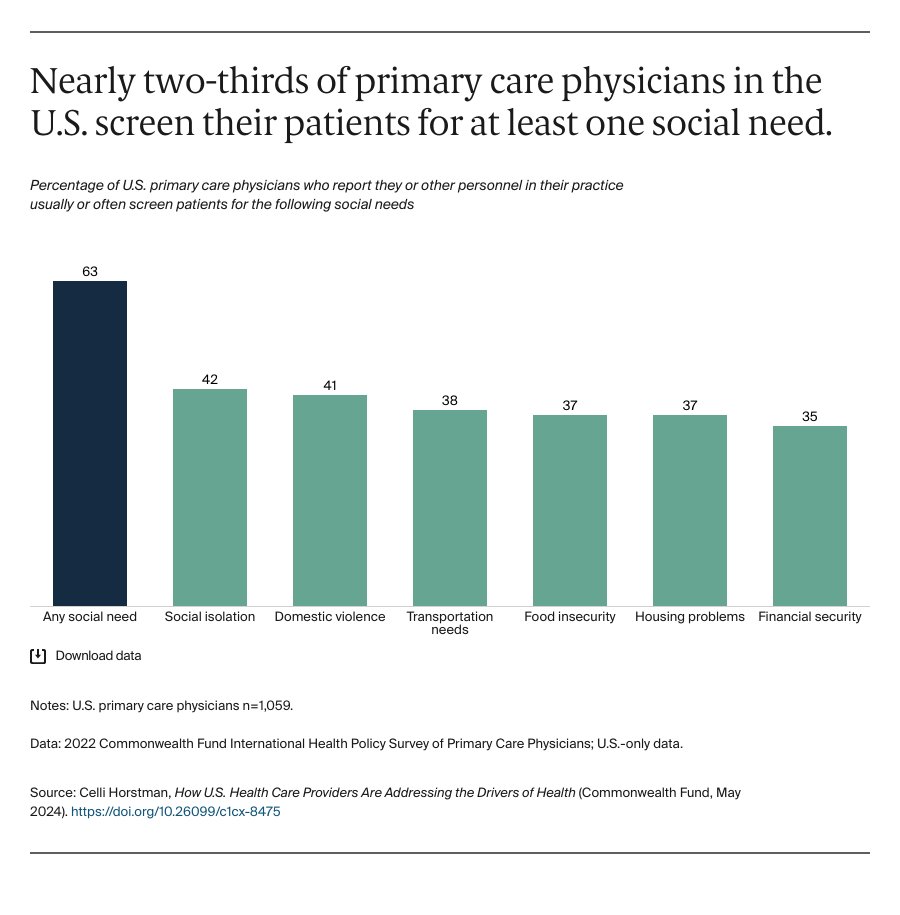

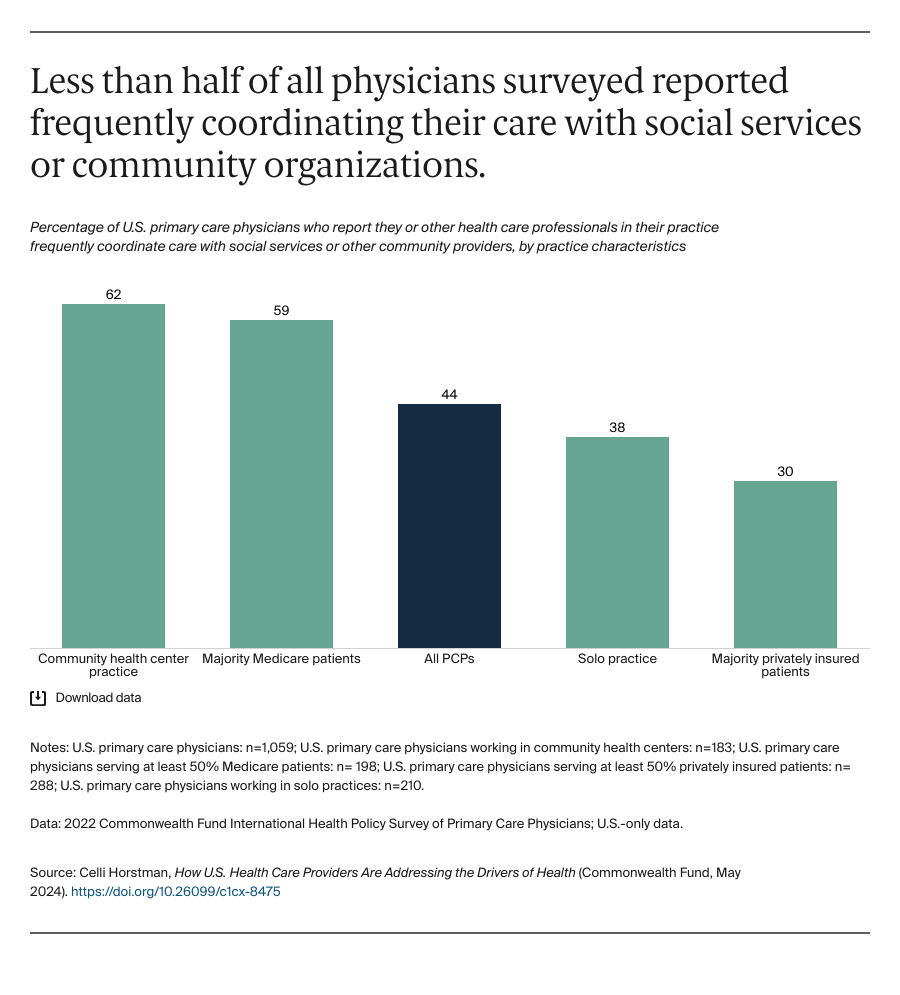

In response, providers and health care organizations are attempting to mitigate these downstream health effects by screening patients and coordinating care with local organizations. While we found high rates of physicians screening their patients for issues like food and housing insecurity, there was a disconnect between the needs patients most worried about and what they screened for. As payers and policymakers encourage physicians to screen patients through data reporting and quality measurement efforts, there is an opportunity to better align screening to patients’ needs.18

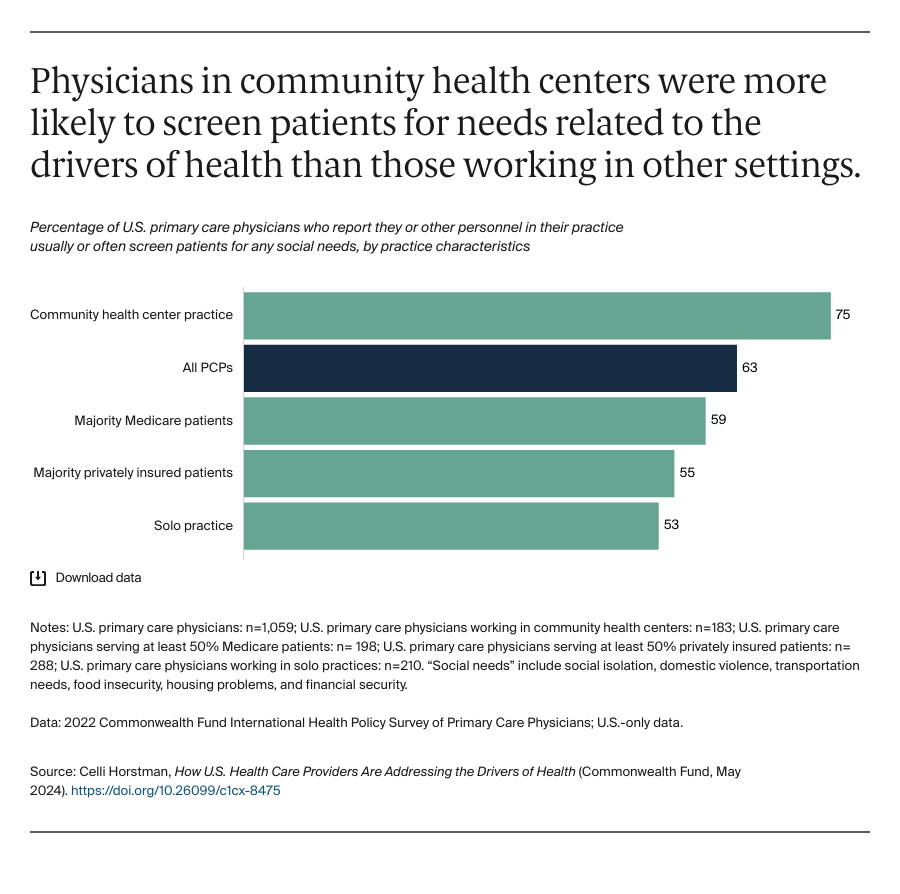

Three-quarters of physicians in community health centers screened their patients and nearly two-thirds reported coordinating their care with local organizations. CHCs were designed expressly to offer comprehensive and accessible health care for underserved populations, and they often employ members of the community.19 Their patients’ needs, strong community ties, and mission-driven operations likely enable them to address unmet social and economic needs. CHCs may offer a learning opportunity for policymakers and practices looking to increase screening and coordination in other care contexts.

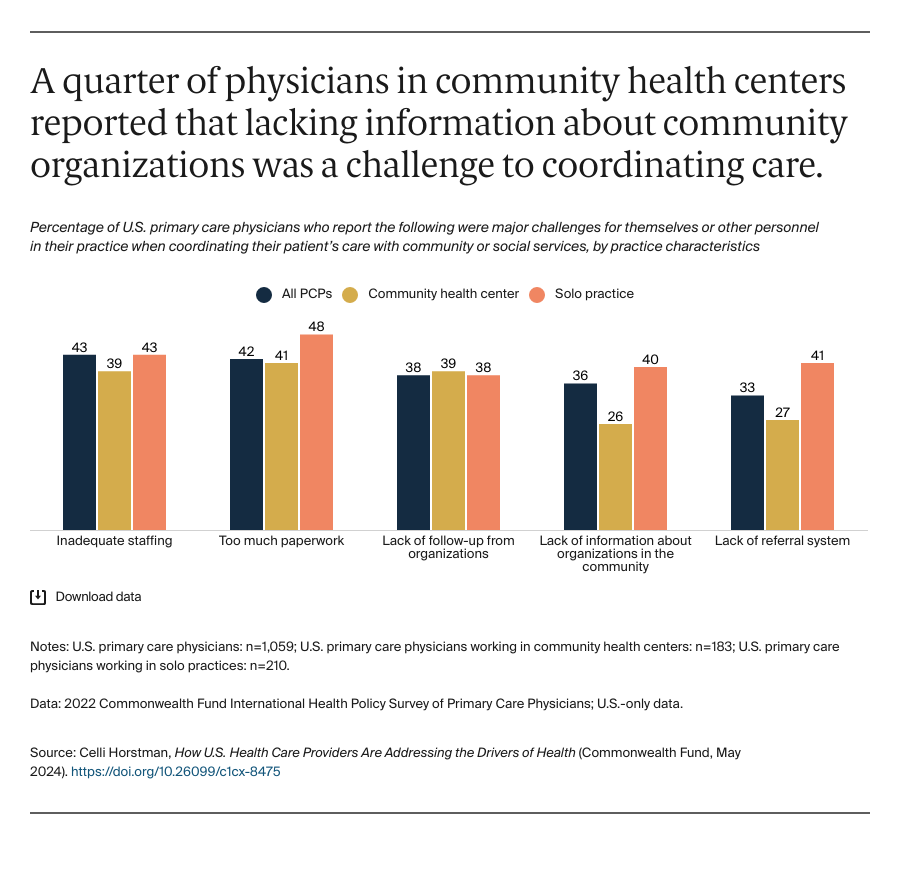

Fewer than half of physicians in solo practices coordinated their care with social service organizations. They reported challenges to coordination like too much paperwork and inadequate staffing. Prior research has found that lack of infrastructure for screening and coordination, including insufficient staff time and financial support, and the need to change workflows, can deter practices from identifying the unmet needs of their patients.20 Policymakers and payers may consider opportunities to better support solo practices, like providing technical assistance to help streamline coordination and referrals, as well as additional funding to hire case managers or care coordinators.

As efforts to address patients’ social needs become more common in clinical settings, some experts warn that practices should avoid assuming that their patients are not already aware of available services, or that organizations within the community have the capacity to take on referrals.21 Instead, health care organizations can engage patients and local organizations throughout the process, from developing a screening methodology to using their resources to invest in their communities and local services. This also may help ensure that practices are screening for needs that their patients are more likely to face.

Through Medicaid, states have several options to address people’s economic and social needs, but not all states are leveraging these opportunities. Many states, particularly in the Midwest and South, have yet to offer nonmedical services through CMS’s waivers and other programs. Through reporting changes, guidance documentation, and more, CMS is making it easier to apply for and use these programs, which could encourage additional states to participate.22