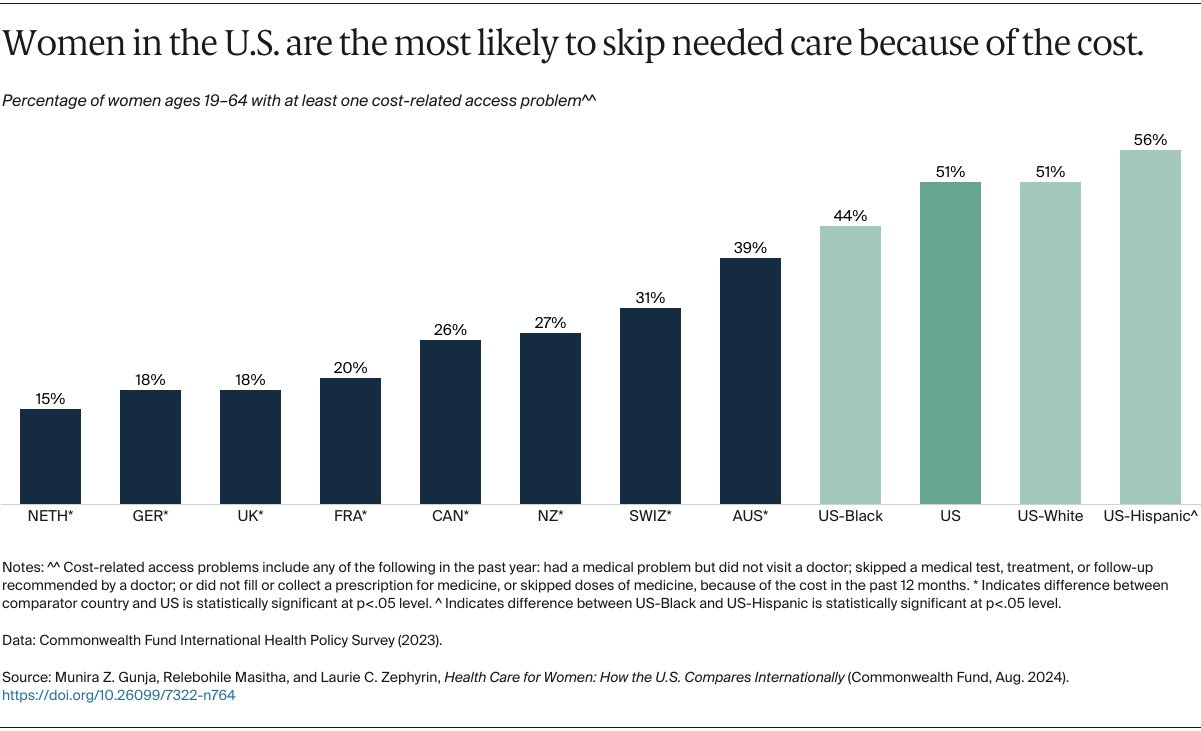

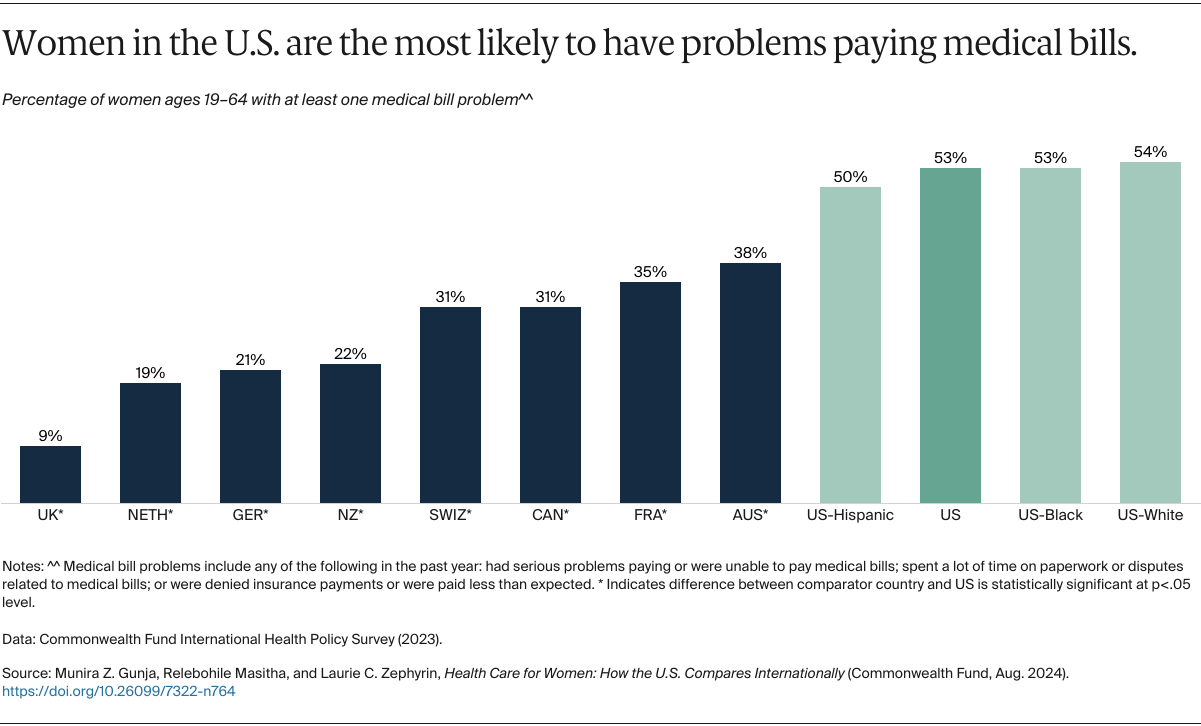

The Commonwealth Fund survey asked women whether they’d had at least one medical bill problem in the past year, including: having serious difficulty paying for care they’d received or being unable to pay a medical bill; spending a lot of time on paperwork or disputes related to medical bills; or having their insurer deny payment or pay less than expected for a claim.

Compared to their counterparts in the other eight countries, women in the U.S. were significantly more likely to report one or more of these medical bill problems, with over half saying they had experienced one or more. Only one in 10 women in the U.K., which provides free care to all residents through the country’s National Health Service, reported a medical bill problem. There were no racial and ethnic disparities in the U.S.

Discussion

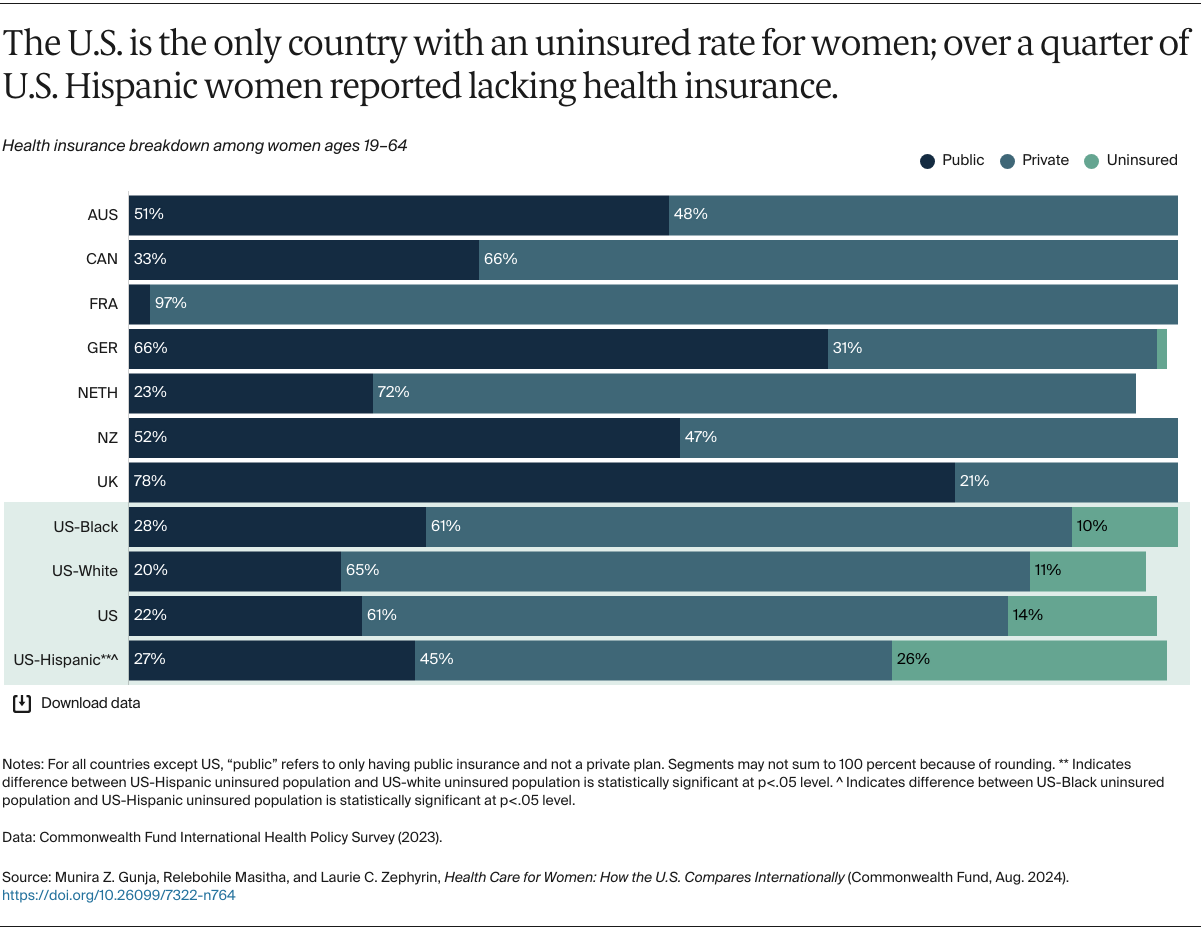

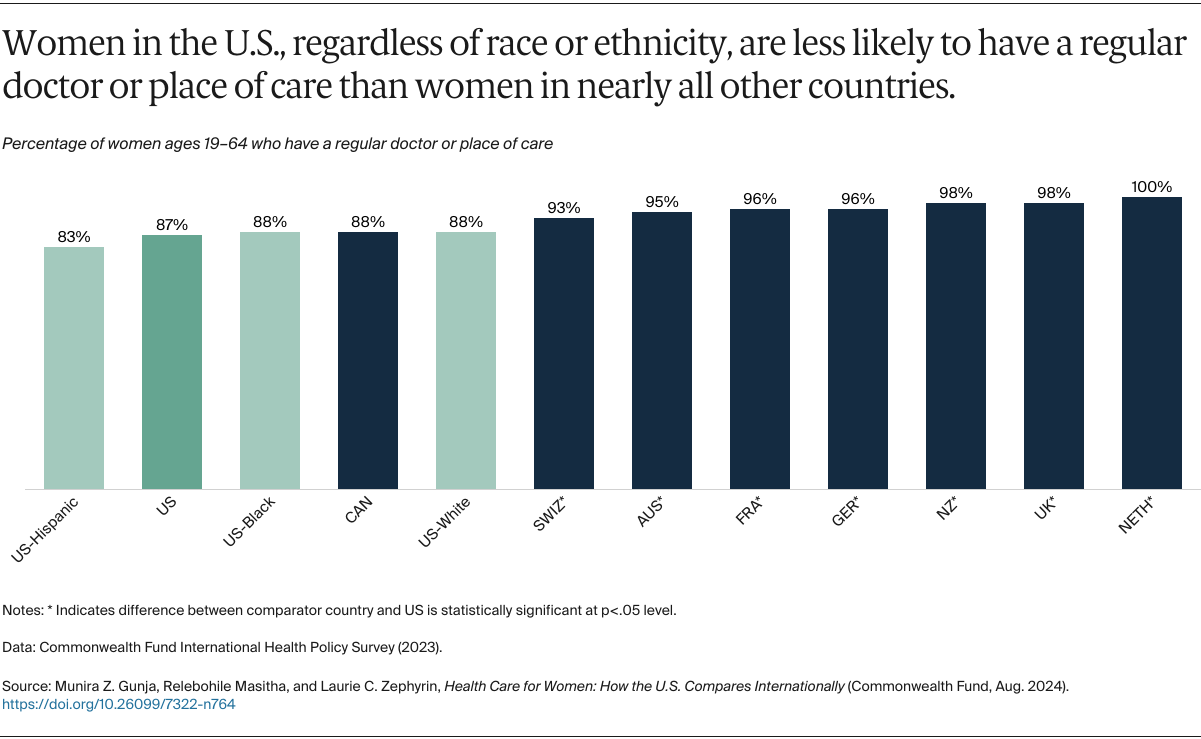

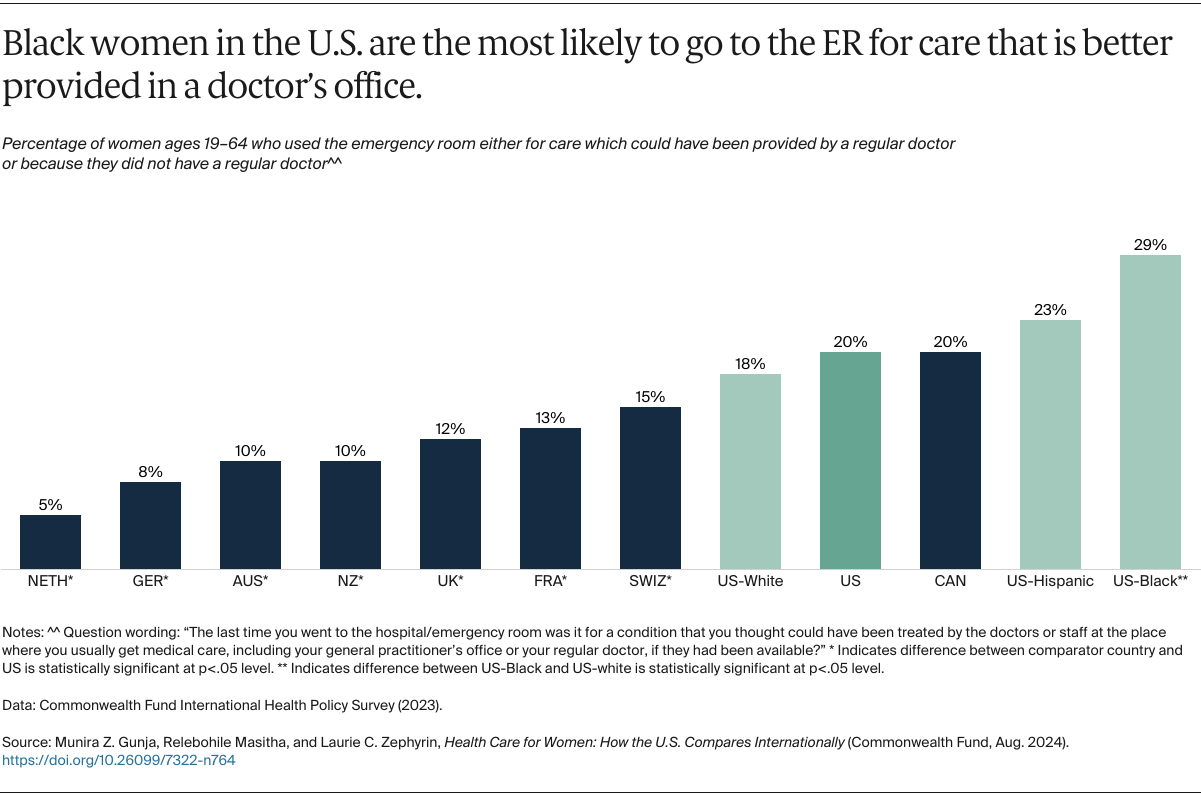

Research shows that investing in women’s health results in a healthier overall population, healthier future generations, and greater social and economic benefits.19 While there is much variation across states on access to care, quality of care, and health outcomes, the United States remains the only wealthy country without universal health care.20

Other countries have made substantial efforts to ensure women are able to get needed health care, which includes primary, mental, maternal, and social care. In addition to ensuring coverage for all, the other nations in this analysis generally cap annual out-of-pocket costs for covered benefits, provide cost-sharing exemptions for primary care and certain other services, and offer additional safety nets based on income and health status.21 For example, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, and the U.K. impose no cost sharing for primary care visits, and France waives all copayments for care related to long-term chronic mental illnesses. Maternal care, including postpartum care, is free in most of the countries we studied and includes home visits by a nurse.22

While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) did away with cost sharing for preventive services like wellness visits, immunizations, and cancer screenings, U.S. women still can face high out-of-pocket costs for other care. Moreover, although a recent circuit court ruling has preserved this ACA provision in Braidwood Management v. Becerra — a case that challenges the guarantee of free preventive services for privately insured individuals — that could change as the case winds its way through the courts.23 With a future ruling in the plaintiffs’ favor, we could see less use of these services, especially among women with lower income, and worsening health outcomes.24

U.S. policymakers could expand on the ACA’s reforms to allow all women to get comprehensive and affordable health care. For example, by enhancing marketplace plan subsidies and covering those low-income individuals who fall into Medicaid’s coverage gap, they could allow all women to receive primary care services without cost barriers. While the enhanced premium subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act have led to historic gains in coverage in the marketplaces, the subsidies expire at the end of 2025; Congress will need to make those permanent to keep marketplace plans affordable.25 U.S. policymakers also could extend the ACA’s requirement to cover essential health benefits, including mental health care, to the large-group employer plans that cover most Americans.

In terms of maternity care, the ACA’s expansion of eligibility for Medicaid coverage has been associated with better health outcomes in the states that have opted in, particularly lower rates of maternal mortality for Black and Latina mothers.26 Yet 10 states have opted not to expand their Medicaid programs, leaving 800,000 low-income women, who are disproportionately Black or Latina, in the Medicaid coverage gap.27 The 2022 U.S. Supreme Court case overturning Roe v. Wade has also threatened women’s access to reproductive care. Twenty-two states have so far imposed bans or restrictions on abortions. Additional bans and tighter restrictions may further limit women’s health care access.28

The U.S. health care system too often fails women. American women face increasing threats to reproductive health care access, including abortion services, that could have a lifelong impact on physical and mental health. While the nation awaits the outcomes of legal challenges to state restrictions on these services, U.S. policymakers have a number of options to improve health and health care for women.