Scorecard Highlights

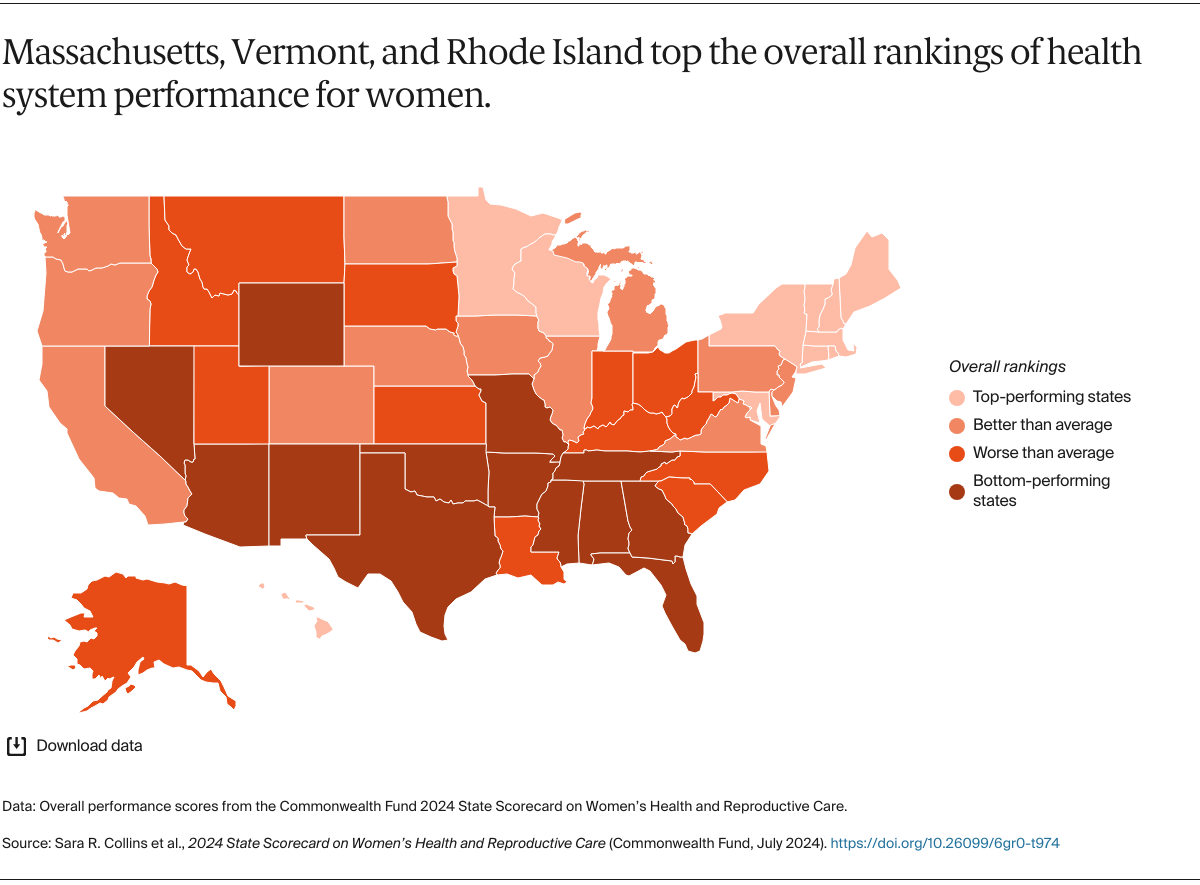

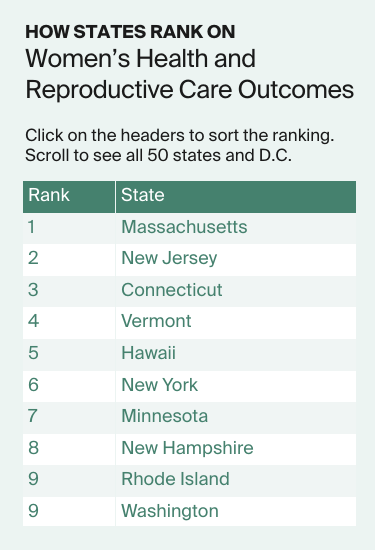

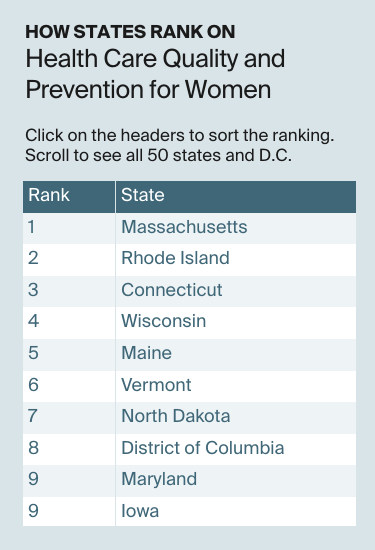

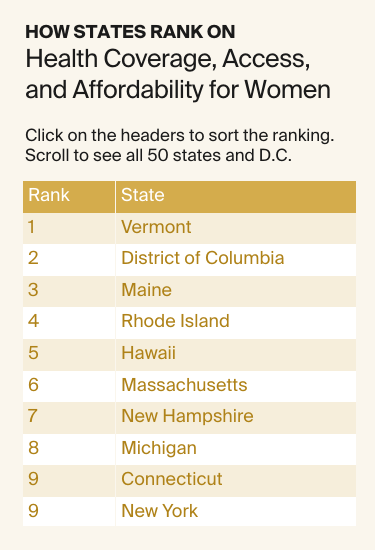

- Massachusetts, Vermont, and Rhode Island top the rankings for the 2024 State Scorecard on Women’s Health and Reproductive Care, which is based on 32 measures of health care access, quality, and health outcomes. The lowest performers were Mississippi, Texas, Nevada, and Oklahoma.

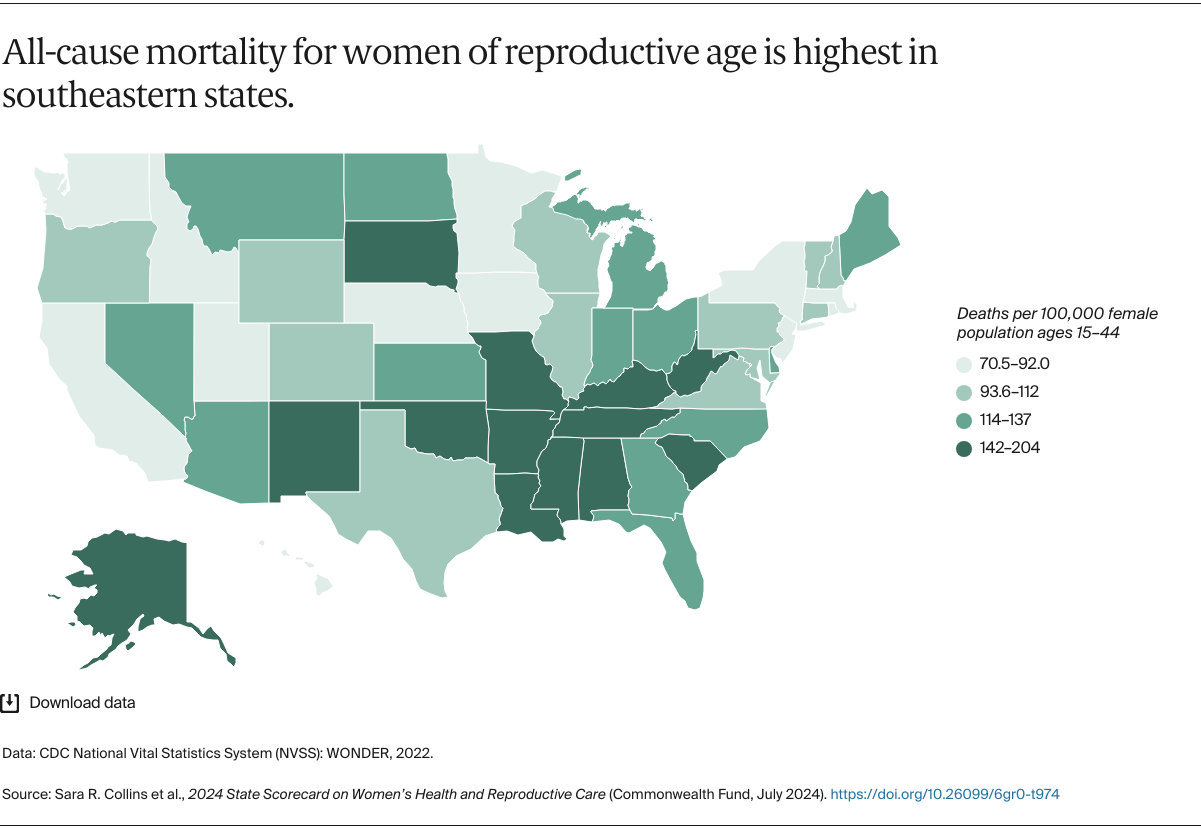

- Deaths from all causes among women of reproductive age — 15 to 44 — were highest in southeastern states. Causes of death include pregnancy and other preventable causes such as substance use, COVID-19, and treatable chronic conditions.

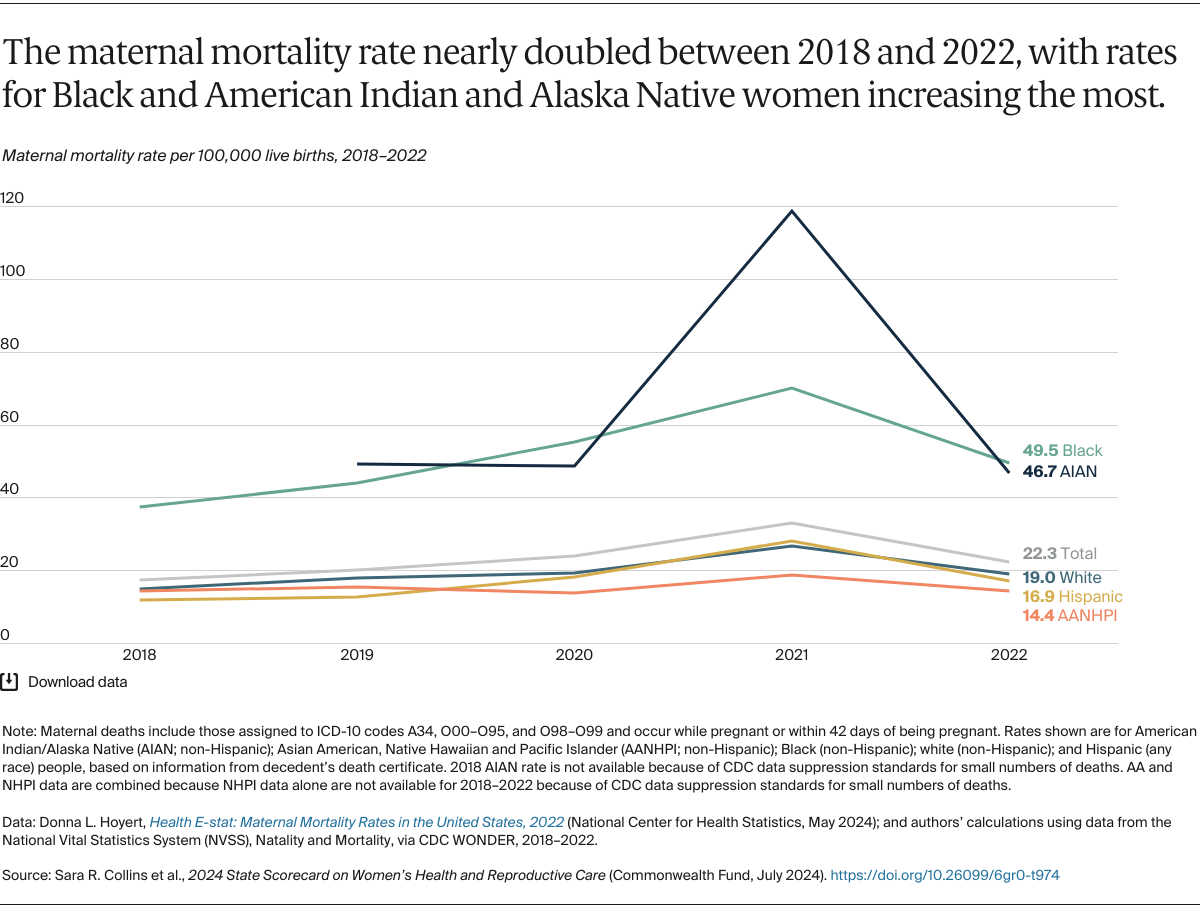

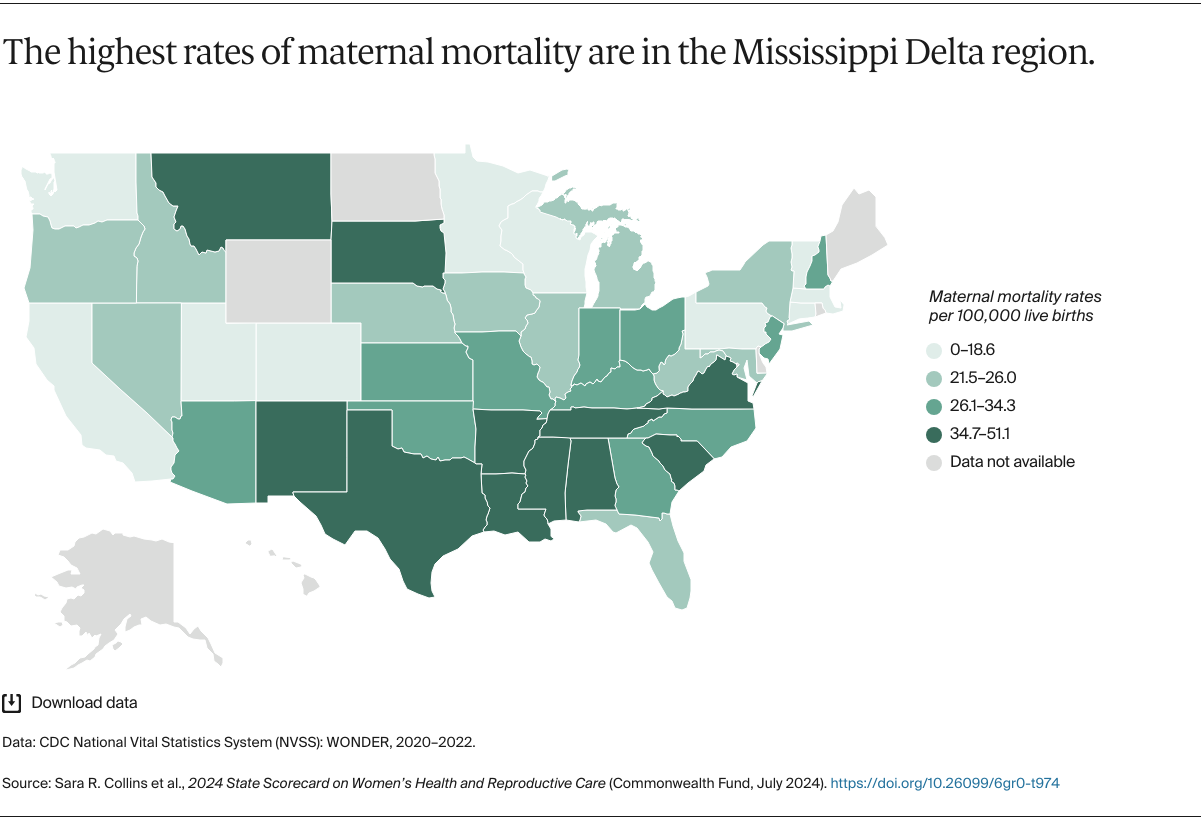

- The highest maternal death rates were in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Vermont, California, and Connecticut had the lowest rates. Nationally, rates were highest for Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) women.

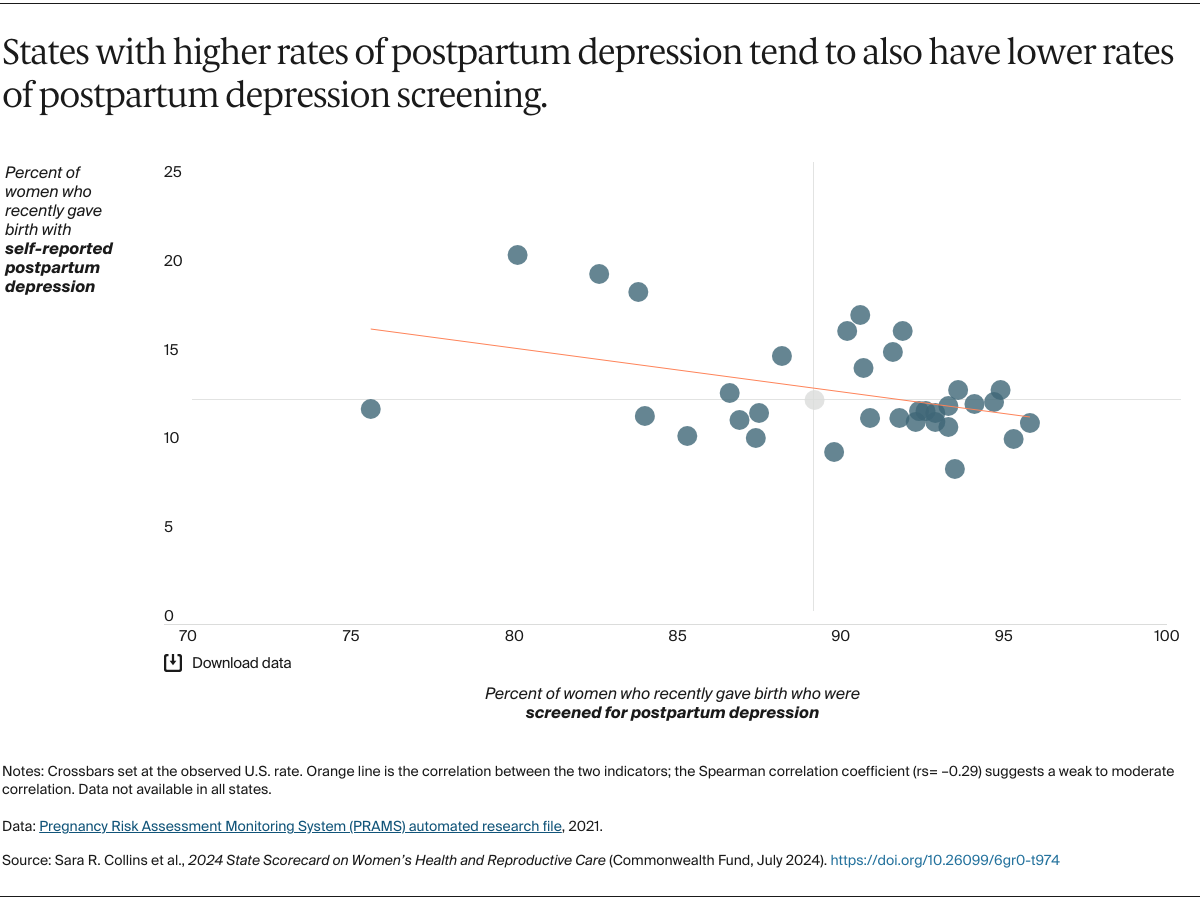

- Mental health conditions are the most frequently reported cause of preventable pregnancy-related death, including deaths by suicide and overdoses related to substance use disorders. States that screened for postpartum depression at the highest rates also had lowest rates of postpartum depression.

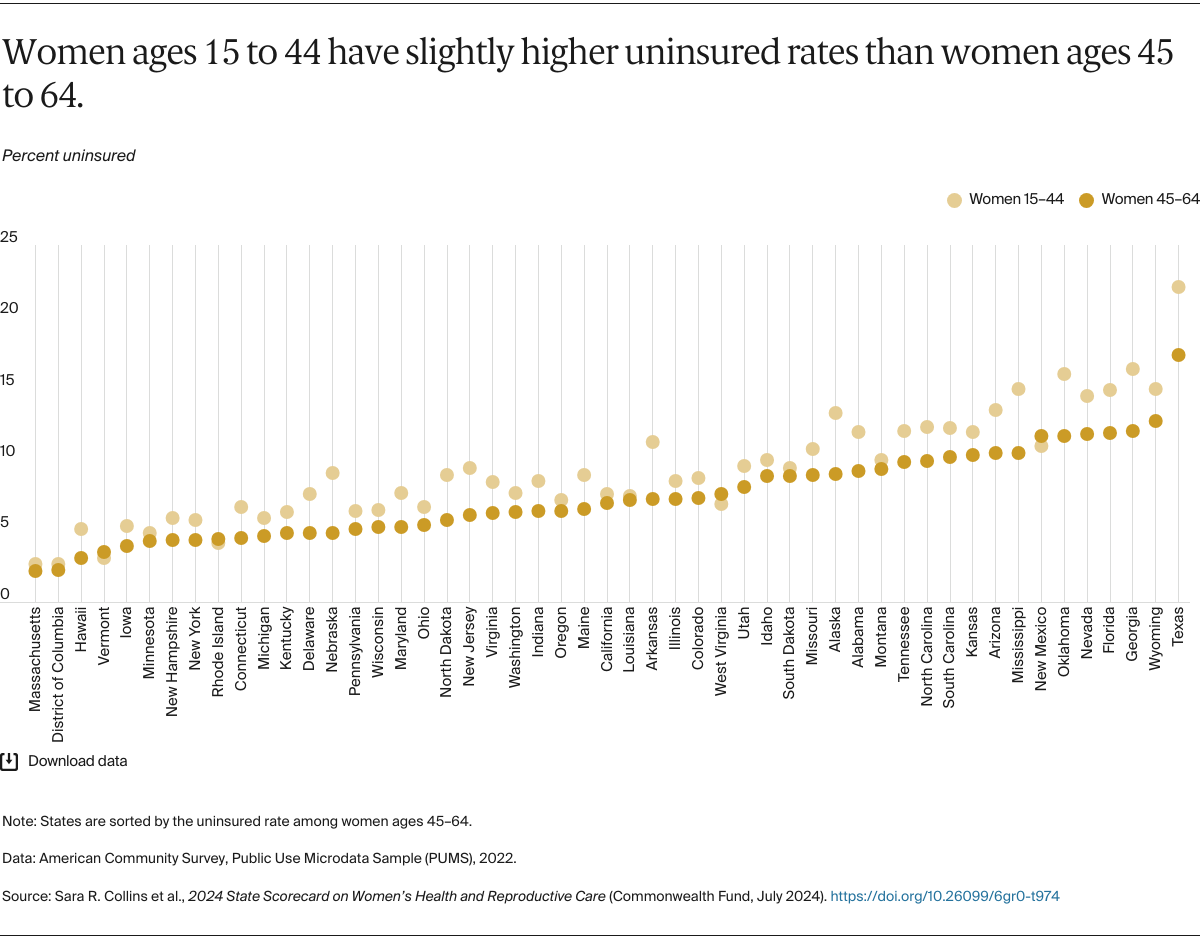

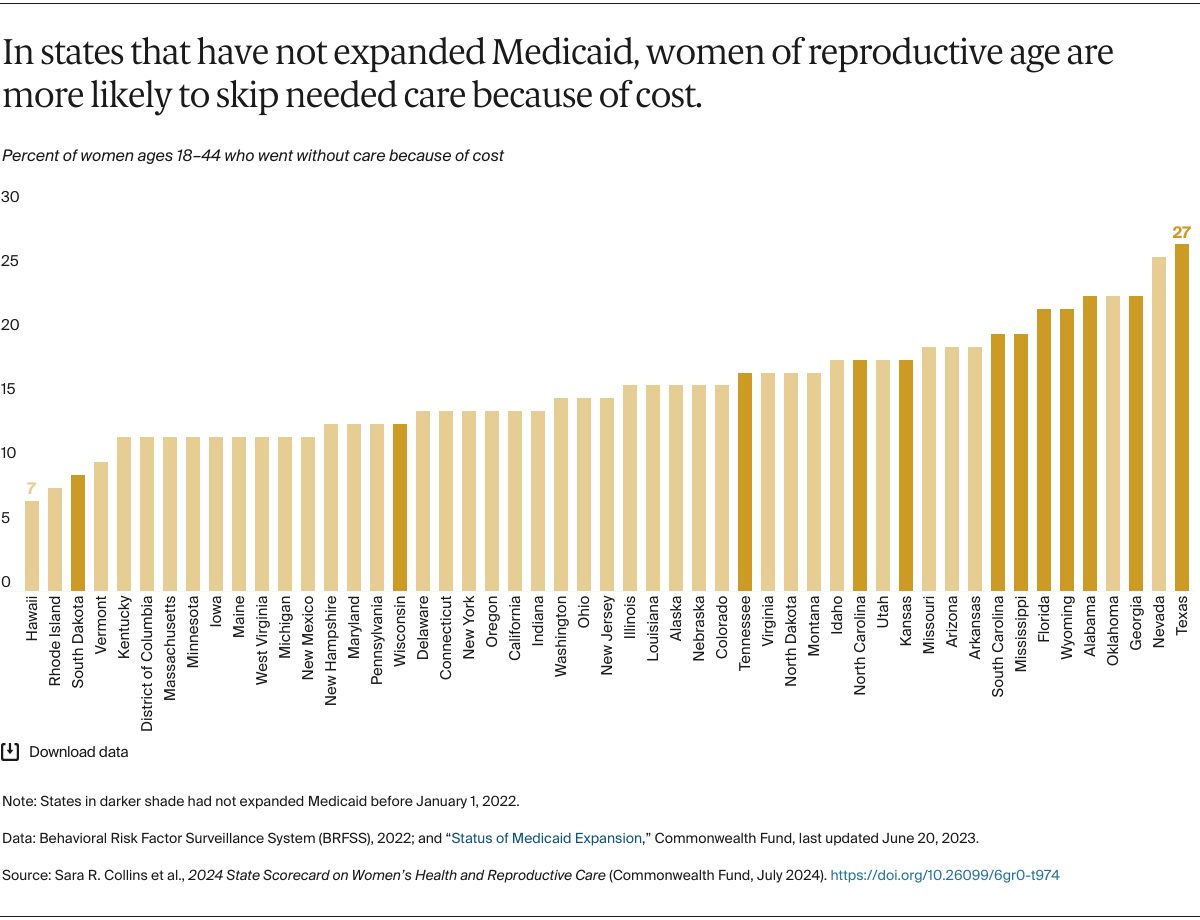

- Among women of reproductive age (ages 15–44), those in Texas, Georgia, and Oklahoma were uninsured at the highest rates; those in Massachusetts, the District of Columbia, and Vermont had the lowest uninsured rates. Women in states that had not expanded Medicaid eligibility were among those most at risk of lacking coverage.

- The U.S. Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade in June 2022 has significantly altered both access to reproductive health care services and how providers are able to treat pregnancy complications in the 21 states that ban or restrict abortion access.

Sections

Overview

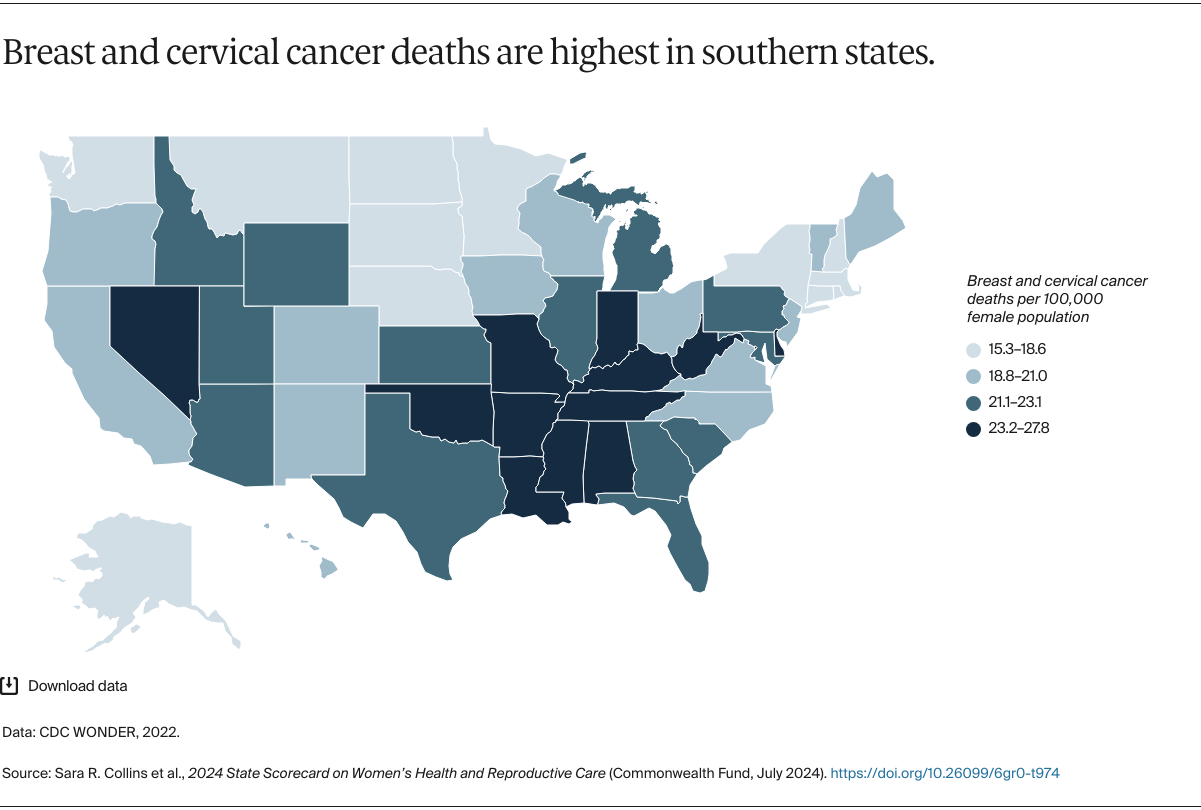

The health of women in the United States is in a perilous place. Deaths from preventable causes are on the rise and deep inequities persist, leading to stark racial differences in maternal mortality and deaths from breast and cervical cancers. Despite a small rebound in women’s life expectancy in 2022, it remains at its lowest since 2006.1

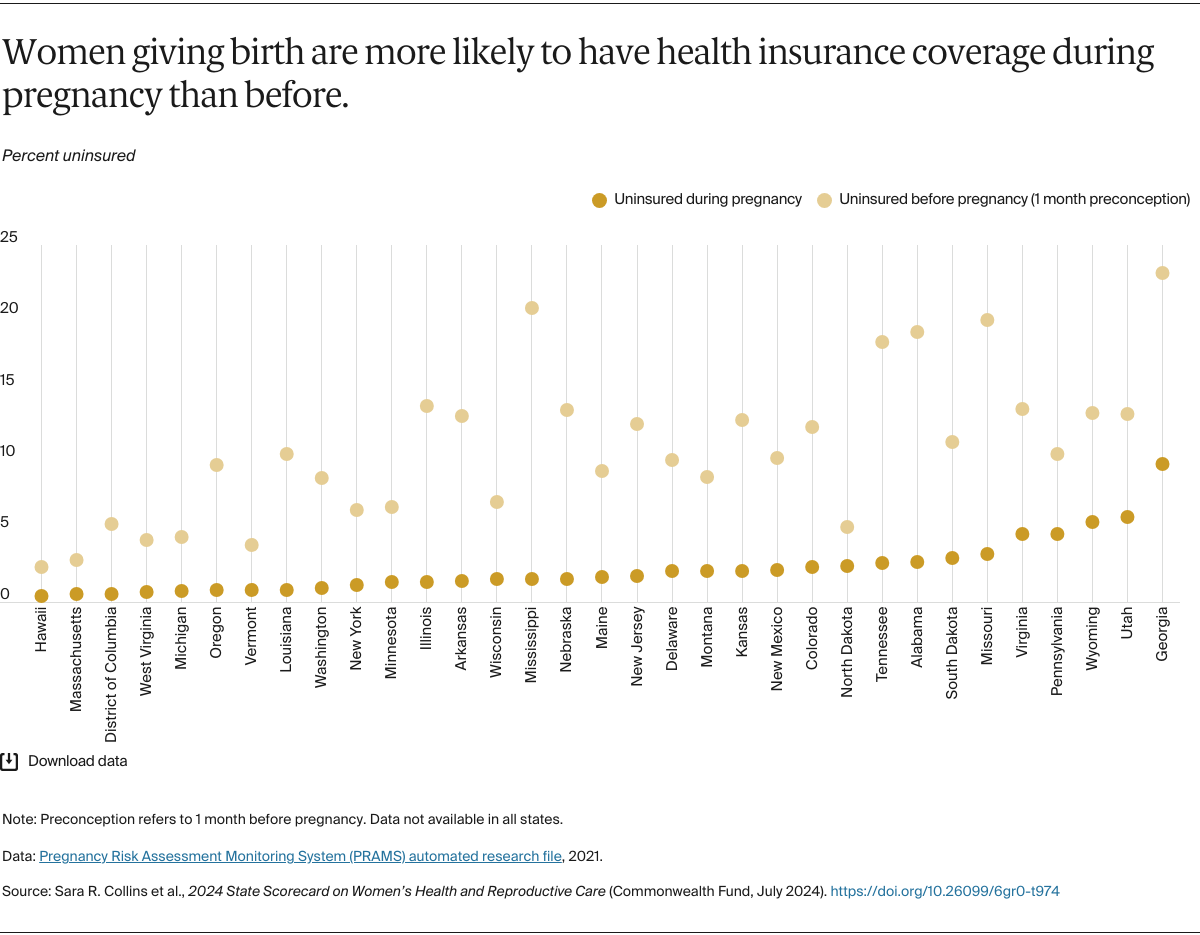

These troubling health trends are occurring while women are experiencing the consequences of state policy choices and judicial decisions that limit their access to the full range of health services and reproductive care. Ten states have yet to expand eligibility for Medicaid, leaving nearly 800,000 women uninsured.2 A highly variable state-by-state approach to the unwinding of pandemic-era Medicaid coverage has left millions of women either newly uninsured or with significant gaps in their coverage.3

These coverage losses are not only interfering with women’s access to care, but they’re also leaving providers that serve low-income women at risk of closure. A recent survey found that 95 percent of community health centers, which care for 40 percent of low-income women nationwide — almost half of whom are covered by Medicaid — reported having patients who were disenrolled.4

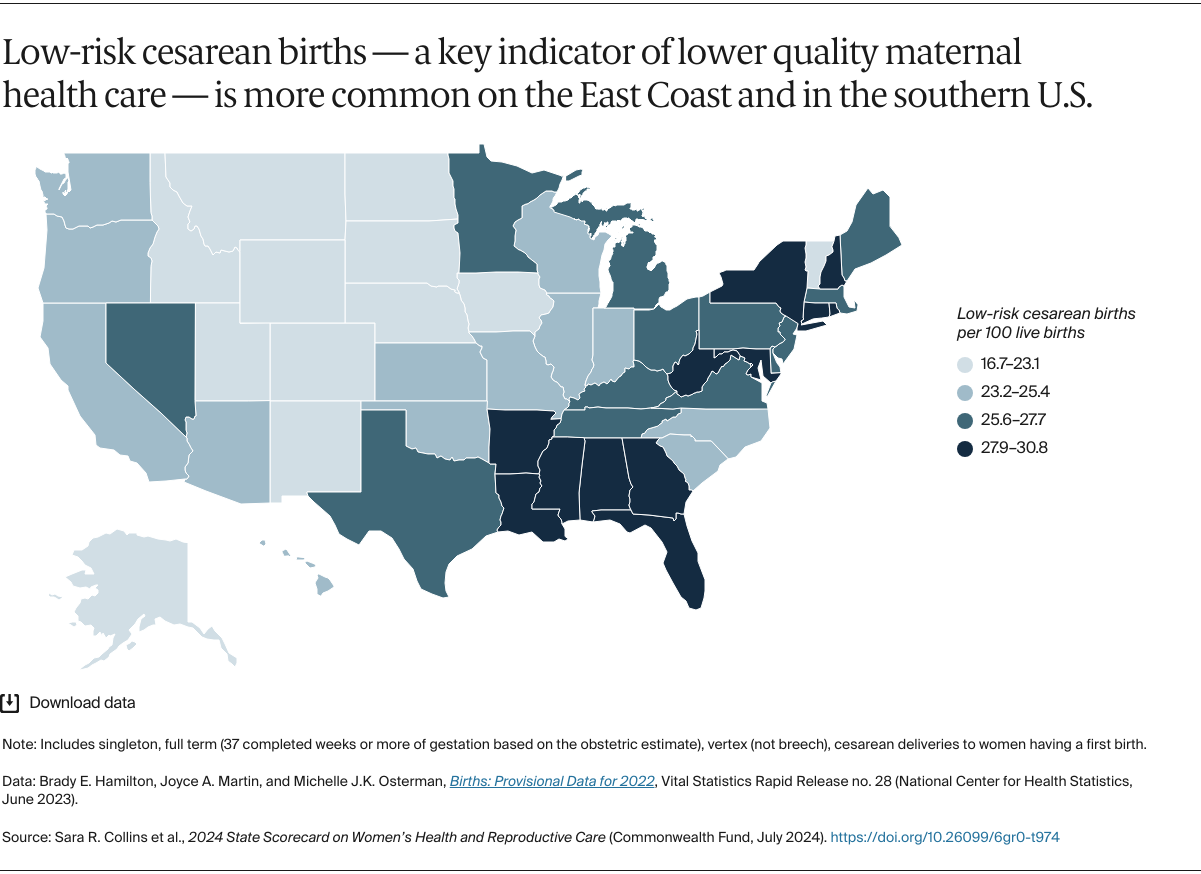

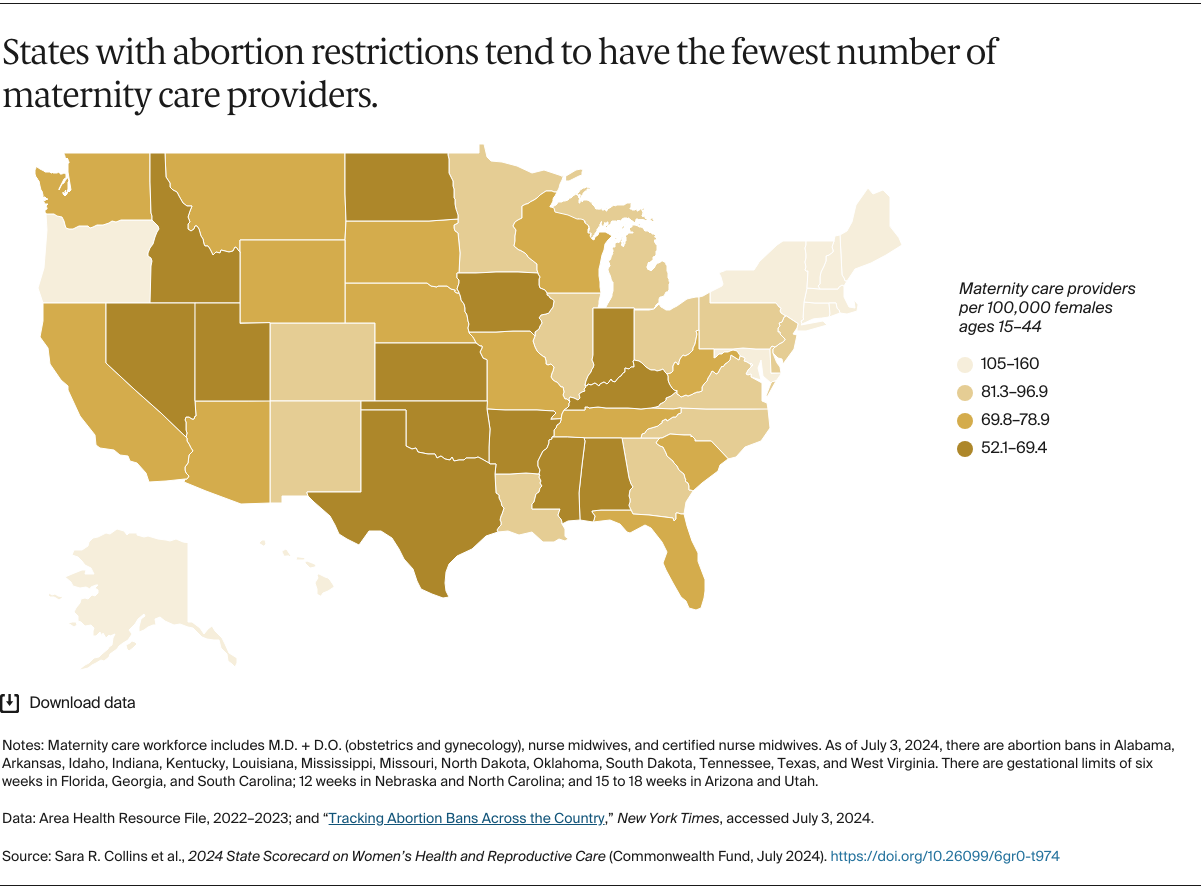

The 2022 U.S. Supreme Court case overturning Roe v. Wade has further fractured women’s health care access and dramatically affected the ability of providers to treat pregnancy complications. In the wake of the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, 21 states have tightened or imposed new limits or bans on abortion.5 Florida’s six-week ban went into effect in April 2024, severely limiting abortion access for women across the South, since all southern states now ban or restrict abortion. Even prior to Dobbs, most of these states had few maternity care providers; higher rates of maternal mortality, especially among women of color; and wide racial and ethnic disparities in their health systems.6 In 2022, the year of the Dobbs decision, residents of more than one-third of U.S. counties had little or no access to maternity care.7