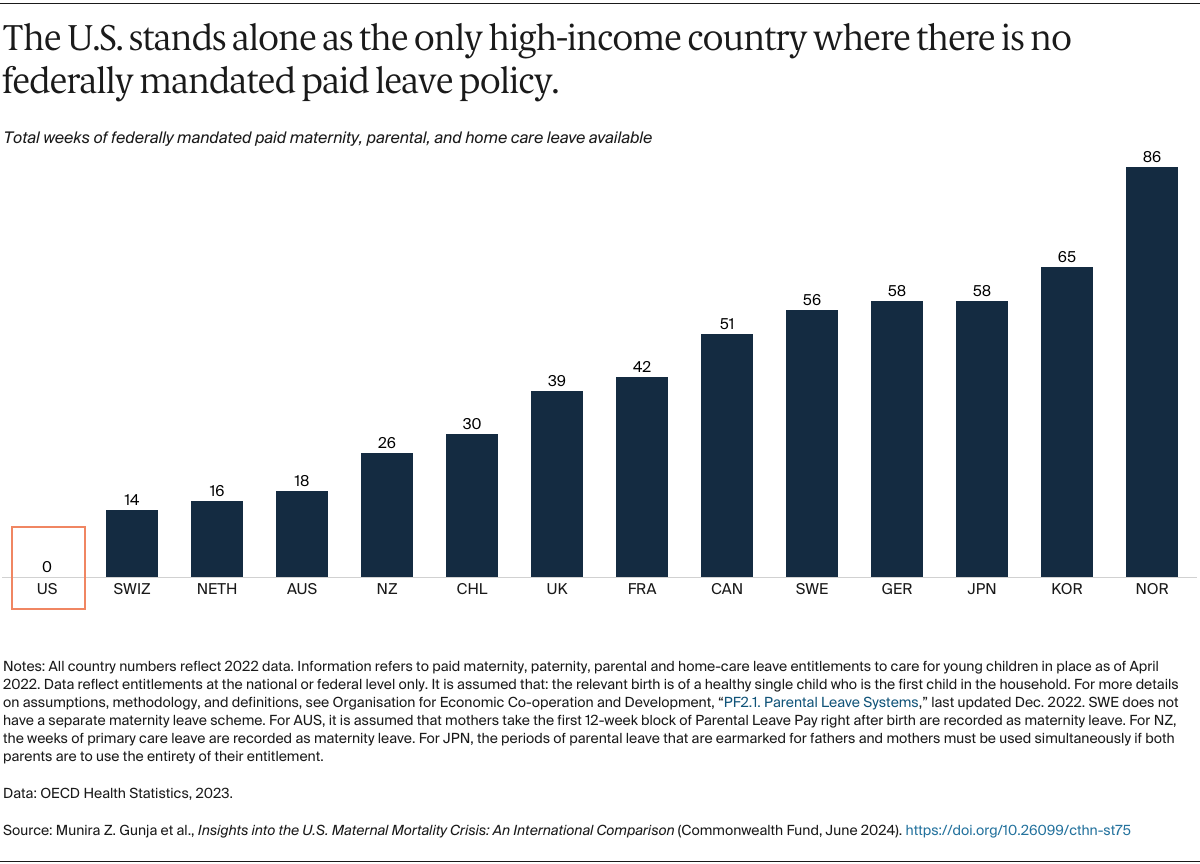

Paid maternity leave allows women to better manage the physiological and psychological demands of motherhood, helps ensure financial security for families, and leads to lower infant mortality.18 All countries included in this study, apart from the U.S., mandate at least 14 weeks of paid leave from work. Several countries provide more than a year of parental or home care leave. While U.S. states and employers can opt to provide paid leave, just over a quarter of American workers have access to paid family leave through either their employer or the state where they reside.19 In the U.S., women who are white and have higher incomes are more likely to take paid leave than Black women. Women who are able to take paid leave have lower rates of postpartum depression.20

Policy Implications

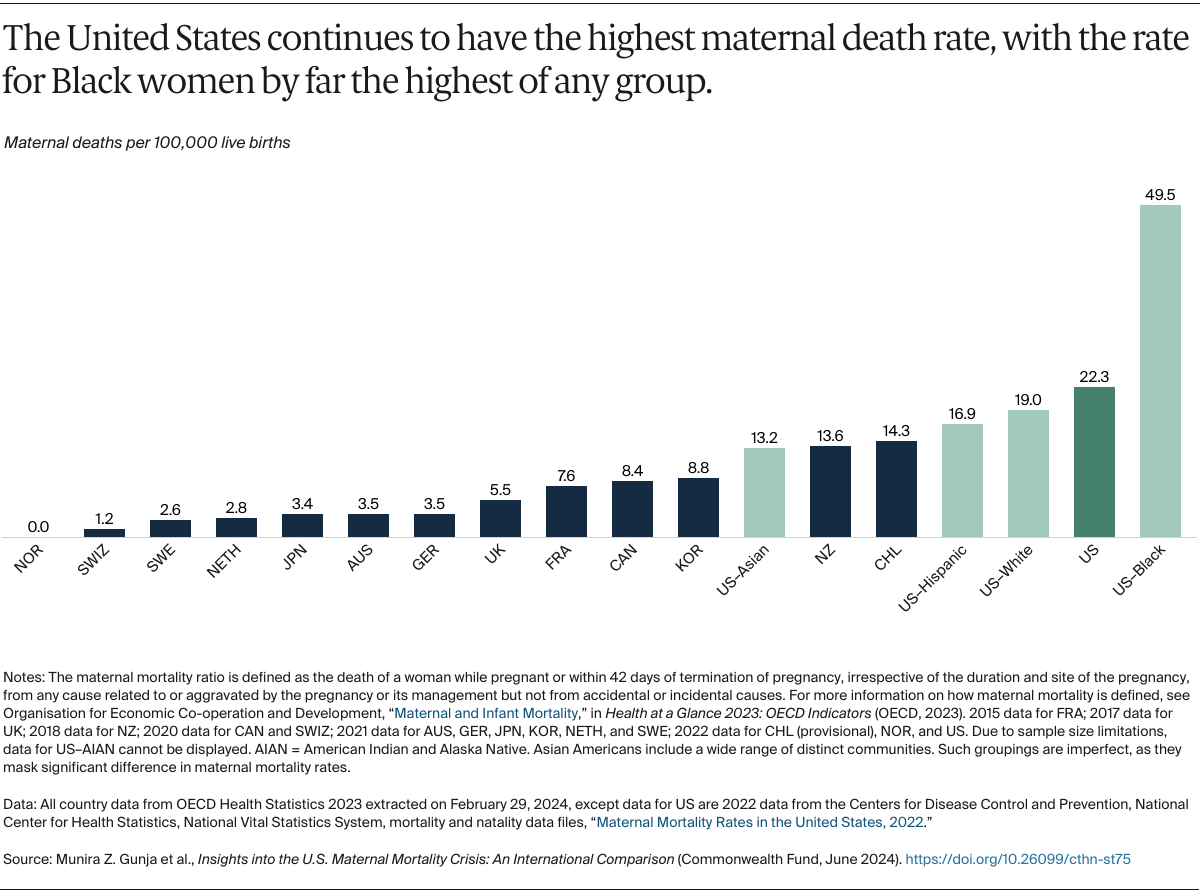

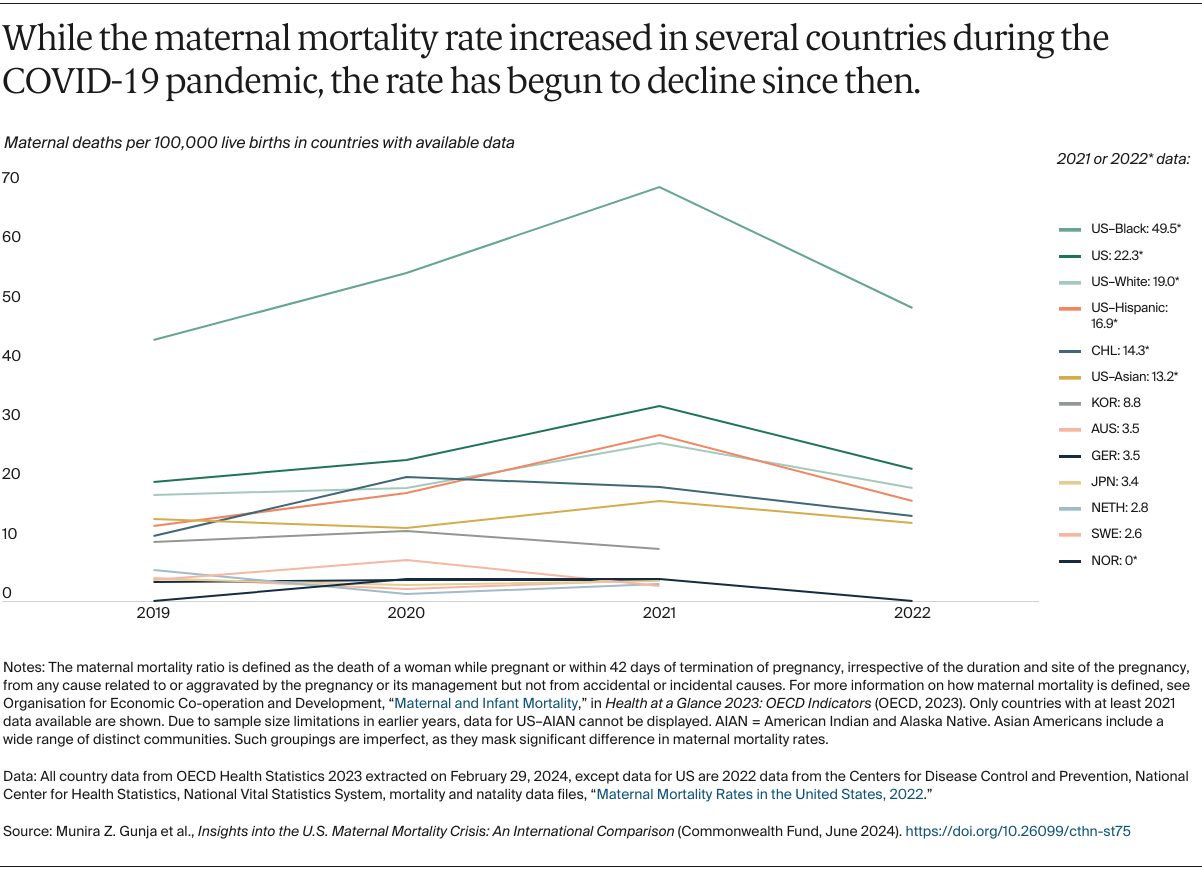

Black women continue to die from pregnancy and childbirth complications at unacceptably high rates, and U.S. women overall are more likely to die from maternal complications than women in other high-income countries. While the number of maternal deaths is lower in 2022 than in earlier years — primarily because there were fewer COVID-related maternal deaths — the United States faces continuing challenges in reducing maternal mortality.

Our findings suggest that an undersupply of maternity providers, especially midwives, and lack of access to comprehensive postpartum support, including maternity care coverage and mandated paid maternity leave, are contributing factors. Because both these factors disproportionately affect women of color, centering equity in any future policy changes will be a key to addressing the crisis.

Although overall maternal mortality rates in the other high-income countries we studied are lower than in the U.S., it should be noted that health inequities among women exist in these other countries, too.21 In the United Kingdom, for example, Black women are four times more likely to die than white women are.22 In Australia, Aboriginal women are about twice as likely as non-Aboriginal women to die from maternal complications.23

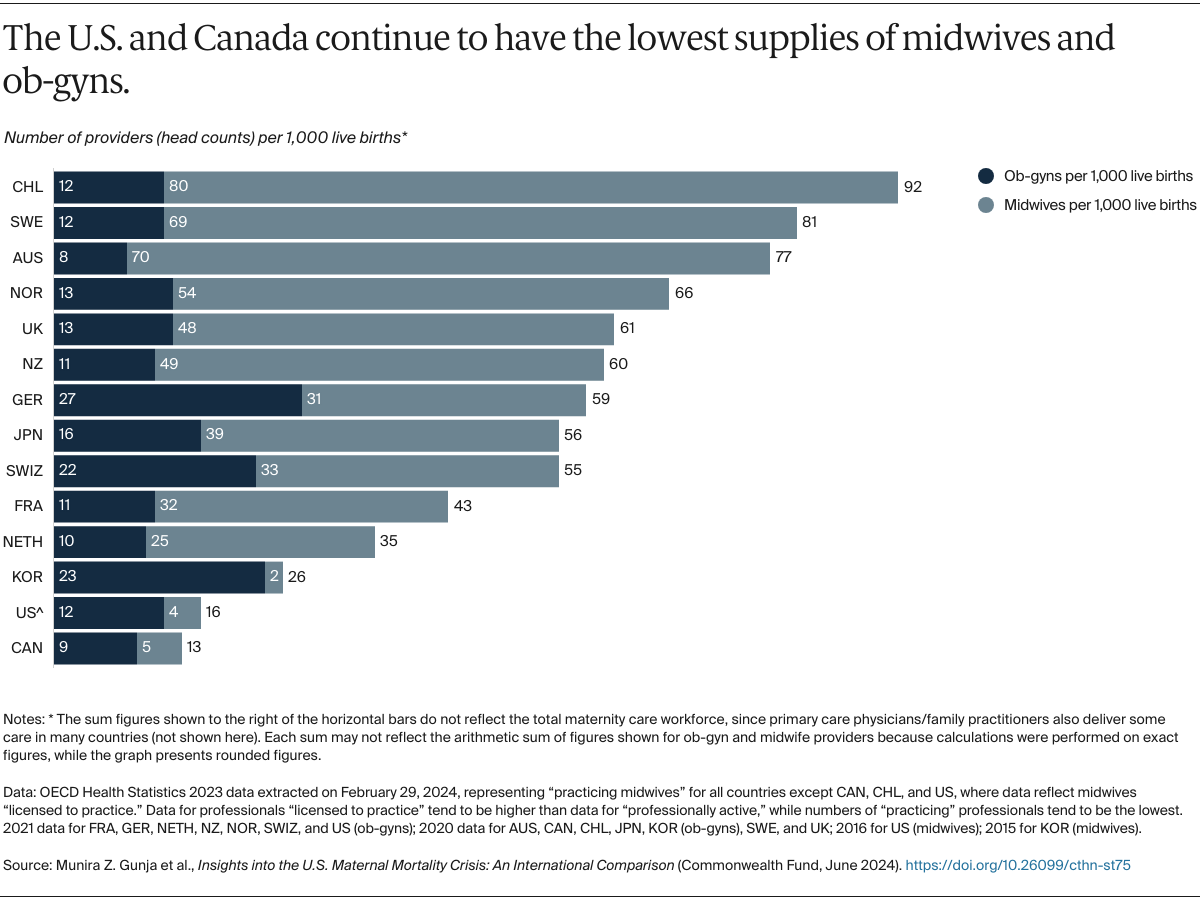

Midwifery Care

Outside the U.S., midwives are often considered the backbone of the reproductive health system. But the U.S. health system does not systematically incorporate midwives into the provision of essential maternity care services, even though these clinicians could improve the quality of care and experience of care for women, particularly women of color.

Some U.S. states have strengthened access to midwives and achieved positive outcomes, but midwifery services are not uniformly covered by private insurance plans across the country. While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires state Medicaid programs to cover midwifery care, Medicaid’s low provider reimbursement rates, coupled with a low supply of midwives, often mean that beneficiaries are unable to access these services.

Midwives also could help address maternity workforce shortages in the U.S., where nearly half of counties lack a single ob-gyn. An estimated 8,000 more ob-gyns are needed to meet demand — a number that may rise to 22,000 by 2050.24

Insurance Coverage

Universal, comprehensive maternity care coverage, along with exemptions from cost sharing, also are the norm in other high-income countries.25 The U.S. is the only one of these countries that does not have universal health care, leaving nearly 8 million women of reproductive age uninsured. The racial or ethnic groups that are the least likely to have health insurance and the most likely to face cost-related barriers to getting care are Black, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders.26

The ACA’s expansion of eligibility for Medicaid coverage has been associated with better maternal health outcomes in the states that have opted in, particularly rates of maternal mortality for Black and Latina mothers.27 Ten states have yet to expand their Medicaid programs, leaving hundreds of thousands of women of reproductive age, disproportionately Black or Latina, in the Medicaid coverage gap and vulnerable to having their coverage terminated 60 days postpartum, as current policy allows. (Forty states have extended their postpartum Medicaid coverage, with several more states planning to do so.28) In addition to gaining postpartum support, expanding Medicaid would improve access to preconception health care for women of reproductive age who are in the Medicaid coverage gap.

The unwinding of the pandemic-era policy of continuous Medicaid enrollment — states restarted eligibility redeterminations in April 2023 — poses an imminent threat to pregnant and postpartum women, who stand to lose their health coverage during this critical period.

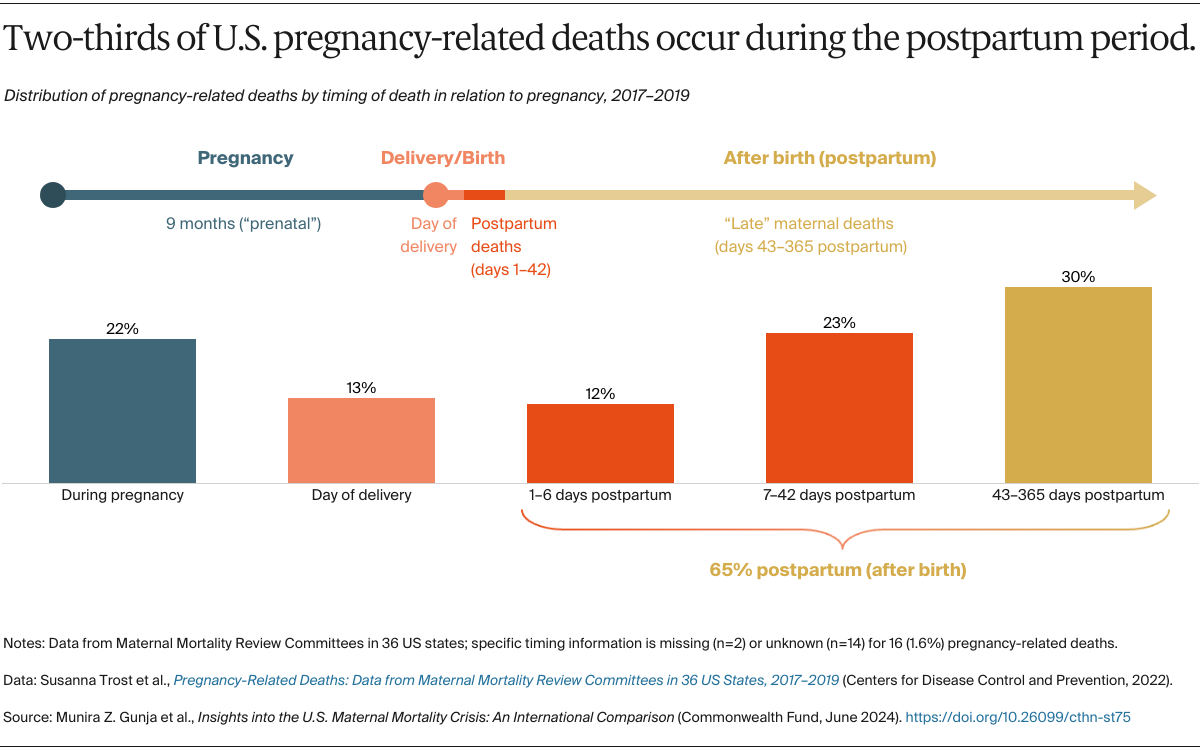

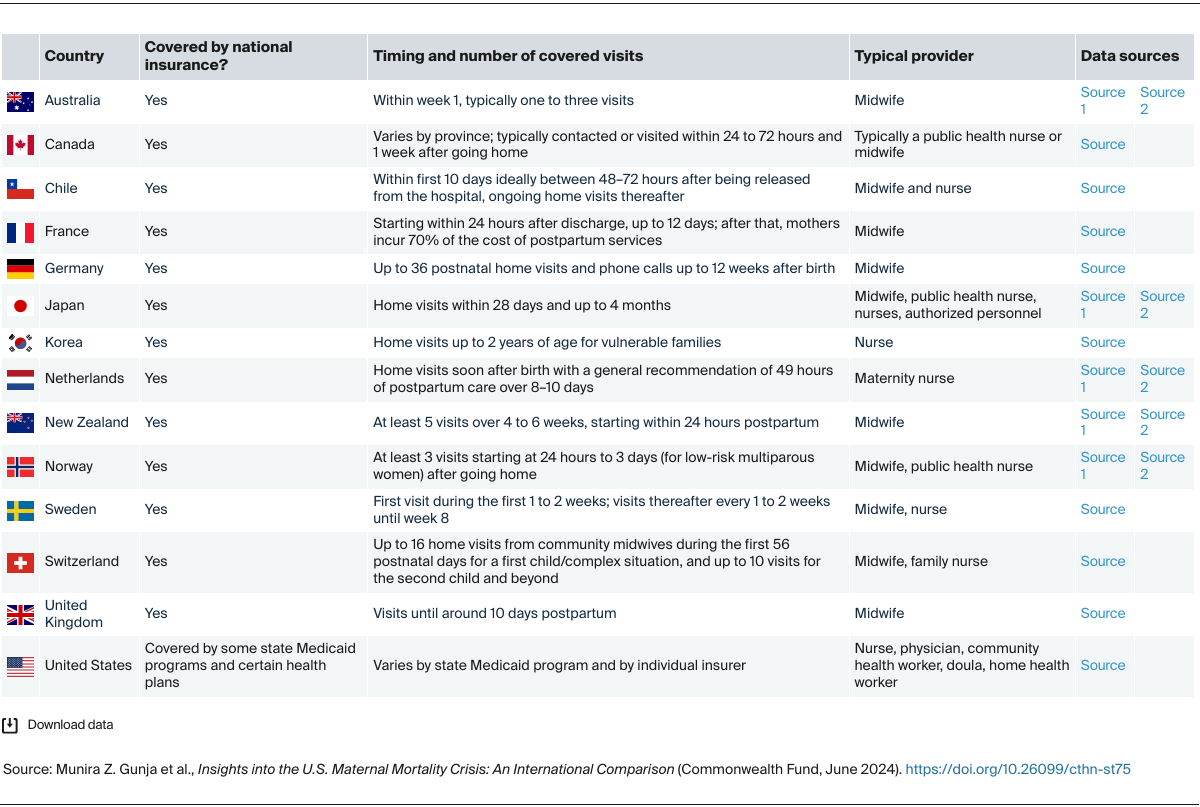

Postpartum Support

Since roughly two of three maternal deaths occur after birth, strengthening postpartum health services should be a priority. The World Health Organization recommends at least four health contacts in the first six weeks following birth, yet two of five U.S. women — more often than not younger, low-income, and uninsured — skip their one postpartum check-up.29 Eliminating barriers that cause people to skip postpartum visits is critical. In Chile, for example, conditional cash-transfer programs provide financial incentives to ensure that mothers can take advantage of health and social benefits, including home visits from midwives and nurses during the postpartum period. Such cash transfers have proven successful in increasing accessing to health services and reducing inequities within the country.30

The U.S. is the only high-income country that does not guarantee all mothers paid parental leave, although 13 states and the District of Columbia have introduced some mandatory paid leave, ranging from six to 12 weeks.31 A federally mandated paid leave policy would be especially beneficial to Black and lower-income women, who are less likely to have a paid leave policy through their employers.32

The well-being of mothers and babies should be a top policy priority in all countries. In the United States, which spends more on health care than any other high-income country, but has much worse maternal health outcomes, policymakers and delivery system leaders could learn a lot from international models of maternity care, including those related to postpartum support and workforce composition. In combination with equity-centered efforts, these examples could inspire the kind of reforms necessary to end the U.S. maternal health crisis.