Abstract

- Issue: The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) is the primary federal law that aims to safeguard access to behavioral health treatment for those with private health insurance. However, enforcing the legislation can be complex, and many health insurers have yet to fully comply with the law’s requirements.

- Goals: Identify challenges, effective regulatory tools, and considerations for policymakers looking to improve access to behavioral health care under the MHPAEA.

- Methods: We interviewed insurance regulators in 10 states and reviewed applicable federal and state law and reports documenting MHPAEA oversight.

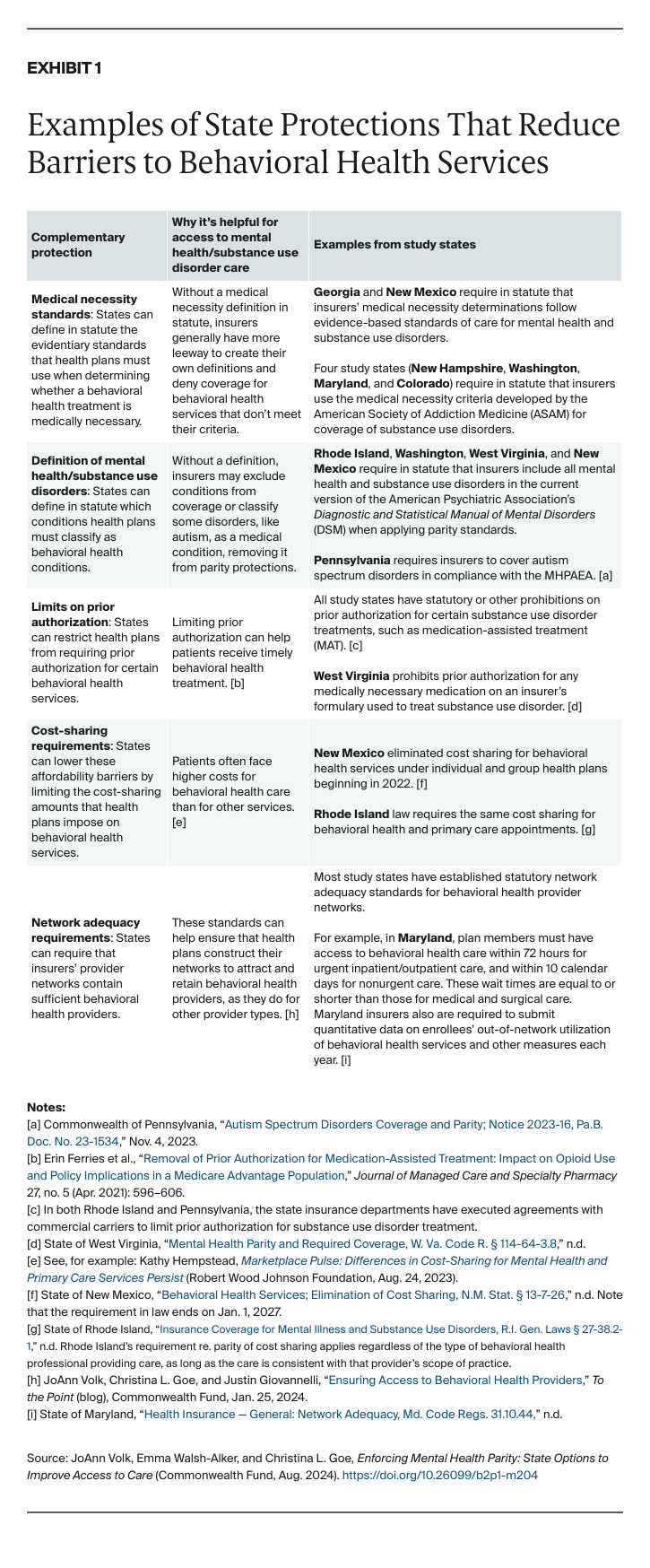

- Key Findings and Conclusion: States rely on several approaches for MHPAEA oversight, including the collection of access and utilization data to identify treatment disparities and market conduct examinations to review claims for MHPAEA compliance. Regulators also evaluate insurers’ comparative analyses of how they determine behavioral health benefits as compared to medical benefits. Many states also have implemented consumer protections that, while not directly linked to the MHPAEA, advance the law’s goals and support regulators’ efforts to enforce it. Supplementing the law with strong standards to ensure adequate provider networks, combined with efforts to grow the behavioral health workforce, would further expand patient access to behavioral health treatment.

Introduction

High demand for behavioral health services, coupled with a shortage of providers and high out-of-pocket costs, has left many U.S. patients — including those with health insurance — struggling to access needed care.1 One important safeguard for consumers is the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA), which aims to ensure that patients do not face greater difficulty getting care for behavioral health conditions than they do for any other care.2 This federal law requires health plans that cover treatment for mental health and substance use disorder conditions to do so on par with their coverage of other health conditions.3 However, enforcing this protection can be complex, in part because the law targets a broad range of potential barriers to care.

The federal government has provided guidance and tools to help insurers and group health plans meet their responsibilities under the law. But in most cases, state insurance regulators are responsible for monitoring insurer compliance with the MHPAEA within their state’s individual and group markets.4 This brief examines what 10 states (Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Washington, and West Virginia) are doing to ensure compliance with the MHPAEA and to help inform other states as they implement strategies to improve patient access to behavioral health care.5 (See “How We Conducted This Study” for more details.)