Introduction

With enrollment growing in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, the private alternative to traditional fee-for-service Medicare, it is important to understand how they affect the health care delivered to their enrollees. While evidence largely indicates that access to care is similar for beneficiaries in MA plans and traditional Medicare, the data around quality of care has been mixed. Little information is available about how the type of coverage affects social drivers of health, care coordination, and other components of care.1

To incentivize the provision of efficient, high-quality care, the federal government makes capitated payments to MA plans, meaning payments are not directly tied to enrollees’ use of services. In contrast, there is no limit on government spending on beneficiaries in traditional Medicare and few incentives to provide efficient care. MA plans may, in turn, either directly or indirectly pass these efficiency and quality incentives along to providers, such as by enabling care to be coordinated more easily, sharing financial risk with providers, and reducing the time they spend on administrative tasks. MA plans may be more likely to pass incentives along to primary care physicians (PCPs), who often help prevent costly, long-term health issues. PCPs also provide referrals to specialists, and MA plans that work closely with PCPs may be able to ensure that their enrollees are referred to less costly in-network providers.

Prior research suggests that MA plans’ incentives for providers may substantially spill over from MA patients to also affect the care and costs of patients in the same clinic covered by traditional Medicare.2 MA plans could also decrease the amount of time PCPs can spend with all their patients if the plans’ utilization management techniques, such as prior authorization or billing requirements, are more time-intensive.

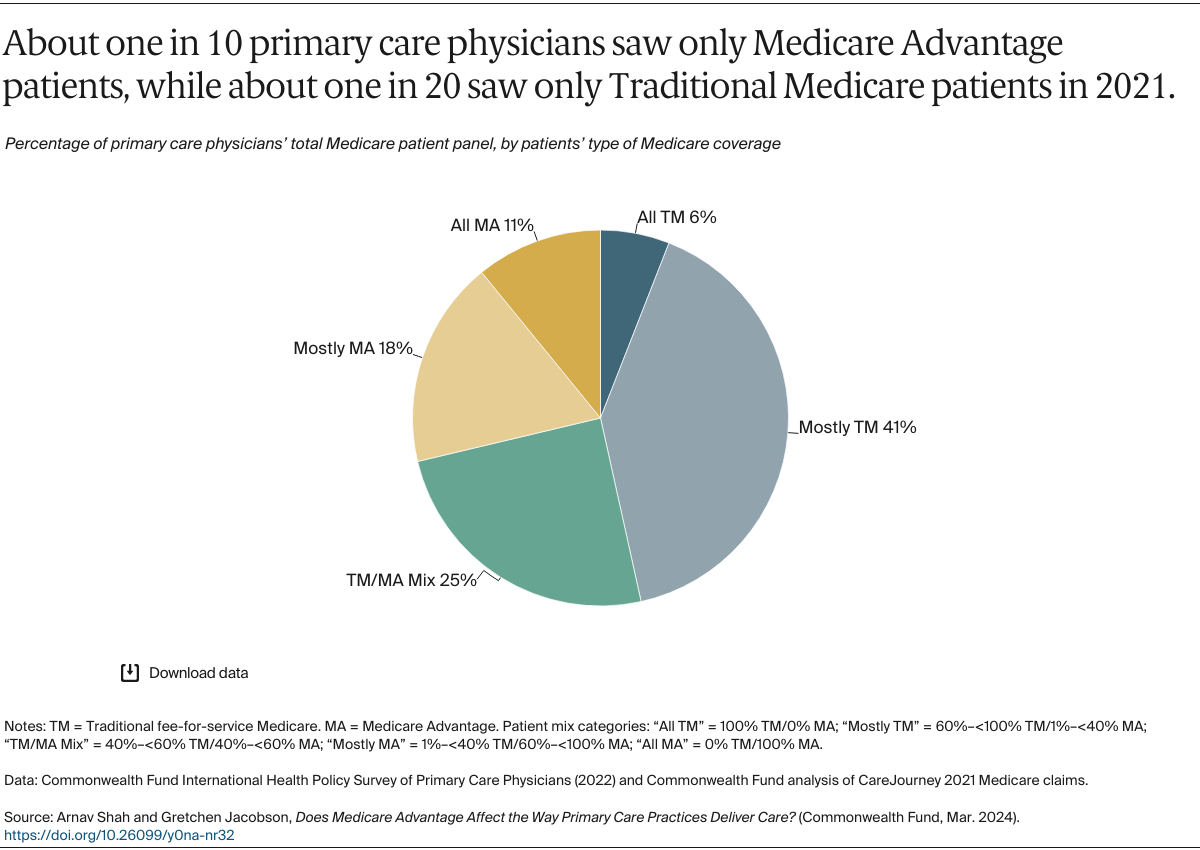

This data brief examines whether PCPs who primarily serve MA patients report differences in care delivery, care coordination, and administrative burden compared to those who mostly serve traditional Medicare patients. The analysis relies on United States–specific data from the Commonwealth Fund’s 2022 International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians, involving 453 PCPs. We also used 2021 Medicare claims data to classify PCPs into three groups (see “How We Conducted This Study” for details):

- PCPs who predominantly serve traditional Medicare patients, meaning 60 percent to 100 percent of their Medicare patient panel was covered by traditional Medicare.

- PCPs who predominantly serve MA patients, meaning 60 percent to 100 percent of their Medicare patient panel was covered by MA.

- PCPs who had a patient panel with a mix of both types of coverage, meaning fewer than 60 percent traditional Medicare but more than 40 percent MA.

We analyzed survey responses with a specific focus on questions about care practices that MA plans could be incentivizing or otherwise encouraging. We discuss how aspects of care reported by PCPs vary across these different patient panel mixes. All respondents included in this analysis had Medicare patient panels greater than 10 people to minimize the likelihood of responses reflecting PCP experiences with non-Medicare patients.