Advancing Community Health Center Involvement in Reentry Care

Expanding CHC involvement in reentry care has its challenges. Addressing these challenges is crucial to the success of reentry efforts, including the new Medicaid reentry initiatives now underway.

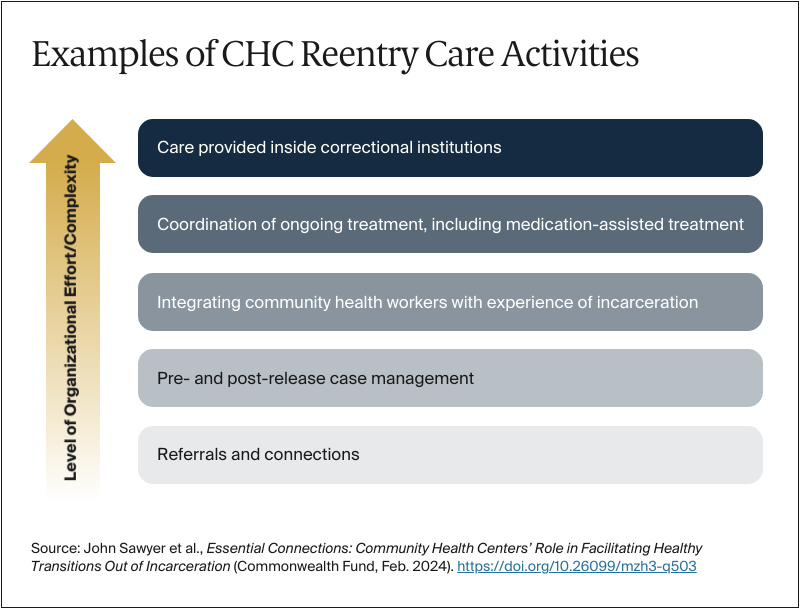

Need for clear federal guidance on CHCs and permissible reentry activities. While Medicaid is only just beginning to cover medical care provided while an individual is incarcerated, CHCs have been heavily involved in a range of pre-release and post-release reentry activities as described above, supported by state and local funds and CHCs’ non-Medicaid revenue. Yet as this capacity among CHCs grows, including in response to new Medicaid policies, there is a need for federal guidance on when, and to what degree, the costs of developing and operationalizing dedicated reentry approaches can be drawn from CHCs’ federal operational grant funding. All CHCs operate within a federally approved scope, including guidelines covering their services, providers, service delivery sites, service area, and target population. These guidelines determine the kinds of activities covered by grant funds and federally provided medical malpractice insurance. CHCs can undertake programs outside this scope, but such programs must operate without federal funding, presenting a major operational barrier to most CHCs. In playing a larger role in reentry-related activities, CHCs would benefit from additional clarity regarding what types of reentry-related services and activities are permissible, as well as the settings in which such services can be furnished. Alongside this clarification, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) could provide dedicated training and technical assistance resources to build CHC capacity in this area, including through implementation of models of care tailored to meet the needs of the formerly incarcerated population.

Workforce and service capacity. A leading barrier to more fully meeting people’s health needs at reentry, identified by nearly all respondents, was building and maintaining the care workforce. Workforce recruitment and retention are broad challenges for CHCs, but they are magnified when it comes to workers with special skills and knowledge.12 One issue is that funding for CHWs who were formerly incarcerated can be difficult to sustain. CHWs who have been incarcerated can also find it particularly difficult to get licensed as other types of health providers because of past convictions. Correctional leaders echoed concerns over staff shortages and the need for training for both clinical and correctional staff.

Aligning a new service model with payment. As noted, the FQHC payment system enables state Medicaid programs, managed care organizations, and CHCs to negotiate alternative payment models. Currently, each health center’s FQHC payment rate is derived from the cost of providing care under its scope of project. An alternative payment model focused on reentry care would entail a change in scope with increased allowable costs, which can translate into advance payments for the cost of implementing a new type of care, selecting the performance measures that will guide payment, and then supporting care over time. While such a model has numerous precedents, technical experts could translate a CHC-based reentry initiative into an FQHC alternative payment model enhancement.13

Building CHCs’ role as a service “hub” in a reentry context. CHCs in most communities represent not only an access point for primary care and other health services, but also a connection point between patients and other social service organizations and resources, including those related to housing, nutrition, transportation, and employment. These connections are especially critical for people returning to communities from incarceration because they often face multiple overlapping needs, and health care access may not be a top priority. Given these connections, CHCs are well-positioned to act as a hub for needed services and should build on partnerships with local reentry service providers (in addition to the types of organizations referenced above) to work toward a seamless, “no wrong door” approach to accessing needed services.

Data infrastructure and data-sharing. Any community reentry project requires sharing data across community and institutional settings. CHCs are especially experienced in capturing and reporting data because of their federal patient, service, expenditure, and performance reporting obligations. This experience is an asset to correctional and CHC collaborations. To support this work, future data-sharing capacity investments should prioritize the integration of CHCs and other community providers.

Conclusion

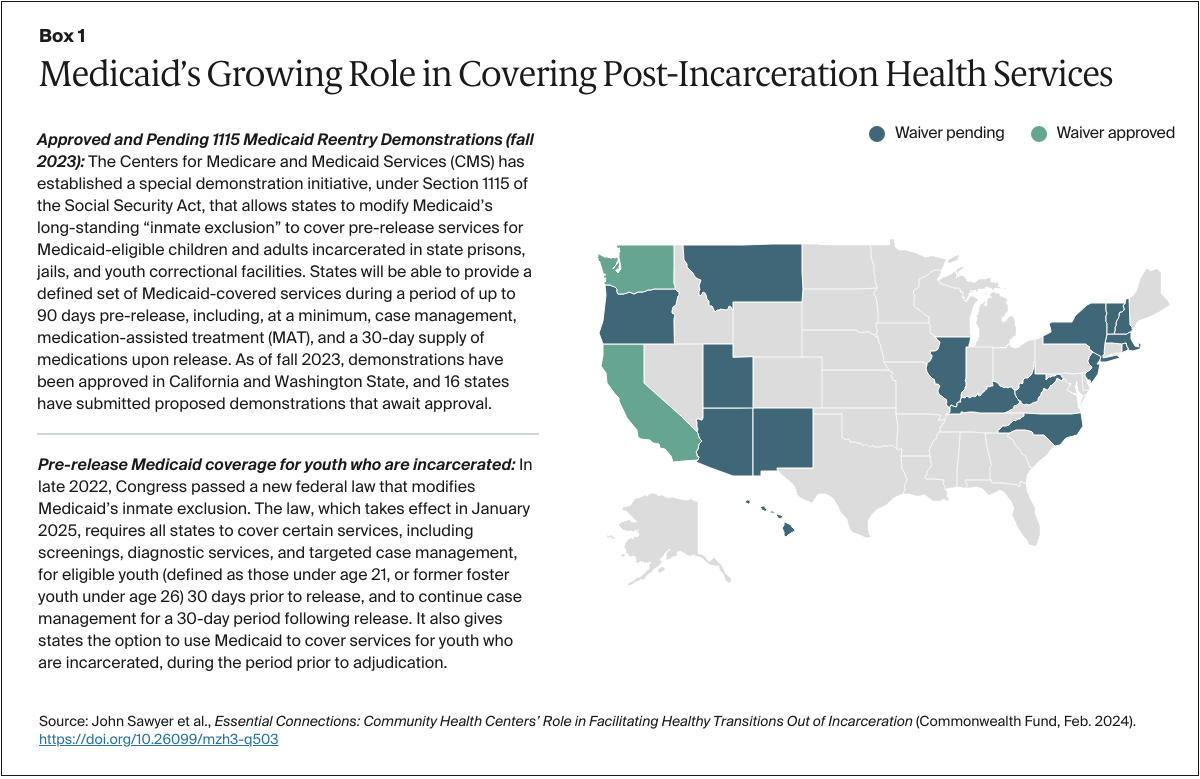

Through statutory changes to Medicaid policies and through Medicaid’s 1115 reentry demonstration, Congress and the Biden administration have signaled the importance of strengthening reentry support and innovation. Additional proposals to enhance Medicaid’s role in this area have been introduced in Congress and are under active consideration. Yet fully realizing the aims of the new Medicaid policies will require a care delivery system capable of operationalizing these reforms.

Community health centers could be important partners for state Medicaid programs and other system leaders working to strengthen reentry care. By both statute and mission, CHCs already serve many of the lower-income, underserved people and communities most affected by incarceration. They also aim to deliver accessible, equitable, integrated care, to have a large role in Medicaid-financed care generally, and to have considerable experience in reentry care.

Achieving these goals means addressing the financing, workforce, data-sharing, and operational challenges that inevitably arise in any initiative to improve health outcomes and health care equity. Because CHCs are experienced in care innovation and offer a unique payment approach through Medicaid, these goals, while challenging, are achievable over time. These efforts may be strengthened through investment in the dissemination and financing of evidenced-based programs, through additional study of how CHCs currently serve formerly incarcerated patients, and through evaluation of innovative care and payment models, including through Medicaid reentry demonstrations. Progress will depend, in part, on efforts to align CHC policy with the new models of health care needed to advance the national goal of enhanced reentry care and better outcomes for people and communities.