Abstract

- Issue: The first wave of COVID-19, from March to September 2020, had significant health, social, and financial consequences for older Americans and their European peers. Comparing their COVID-19 experiences is important for understanding the variable impacts of the pandemic.

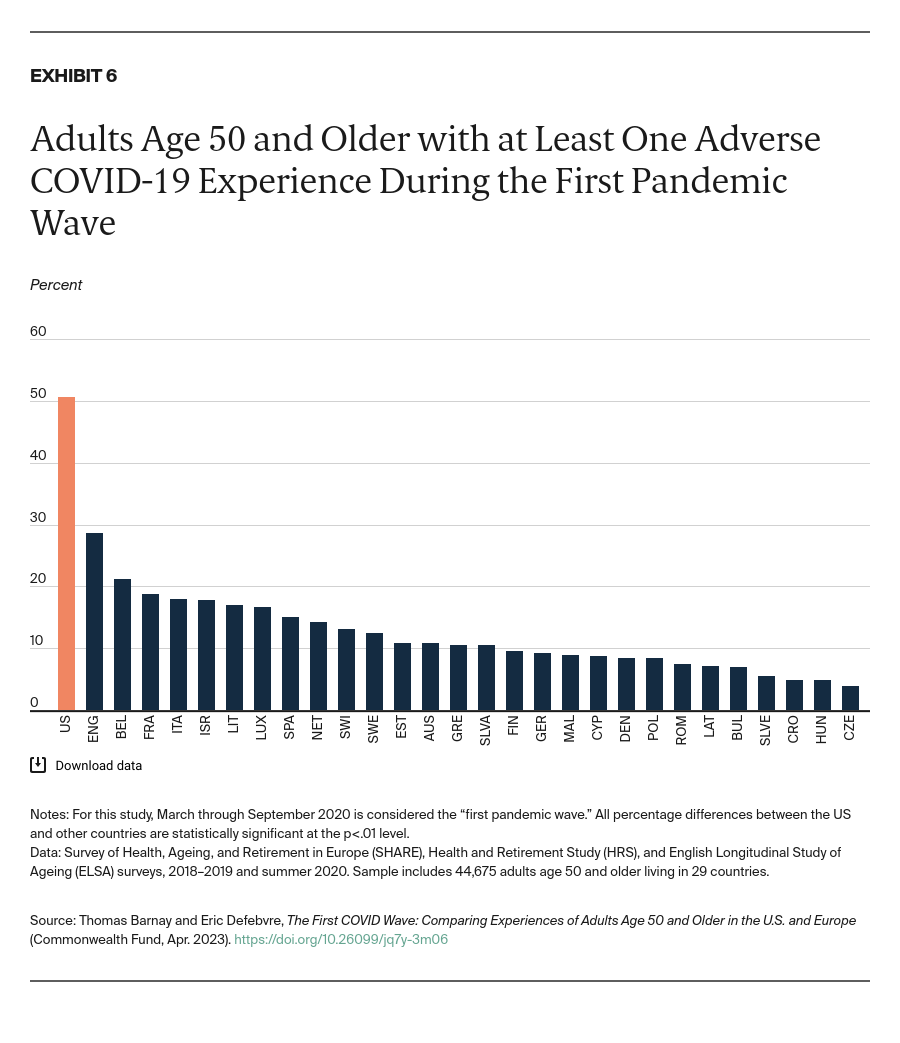

- Goals: Analyze and compare how older adults, who are more vulnerable to the health consequences of COVID-19, were affected during the first wave of COVID-19. We examined how adults in 29 countries were affected by four adverse COVID-19 experiences: being infected with or hospitalized because of COVID-19; forgoing care; experiencing the death of a friend or relative from COVID-19; and losing a job.

- Methods: Responses to three representative and longitudinal household surveys, involving nearly 44,700 adults age 50 and older in the United States and 28 European countries, were analyzed for our assessment of impact: the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), and the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE).

- Key Findings and Conclusion: During the first COVID-19 wave, older Americans were much more likely than their European peers to report at least one of the four adverse COVID-19 experiences we studied. These experiences could have lasting effects on older adults in the U.S.

Introduction

Three years after the COVID-19 pandemic began, the United States remains one of the hardest-hit countries, with more than 1 million confirmed coronavirus deaths, of which more than 91 percent involved people 50 years and older.1 Beyond causing this enormous loss of life, the pandemic has had other significant adverse consequences, including hospitalizations, job loss, and delayed care for millions of Americans.

In this brief, we examine how U.S. adults age 50 and older fared during the first wave of the pandemic in the summer of 2020, compared with their peers in European countries. Using three different databases and questionnaires, we focused on four adverse experiences:

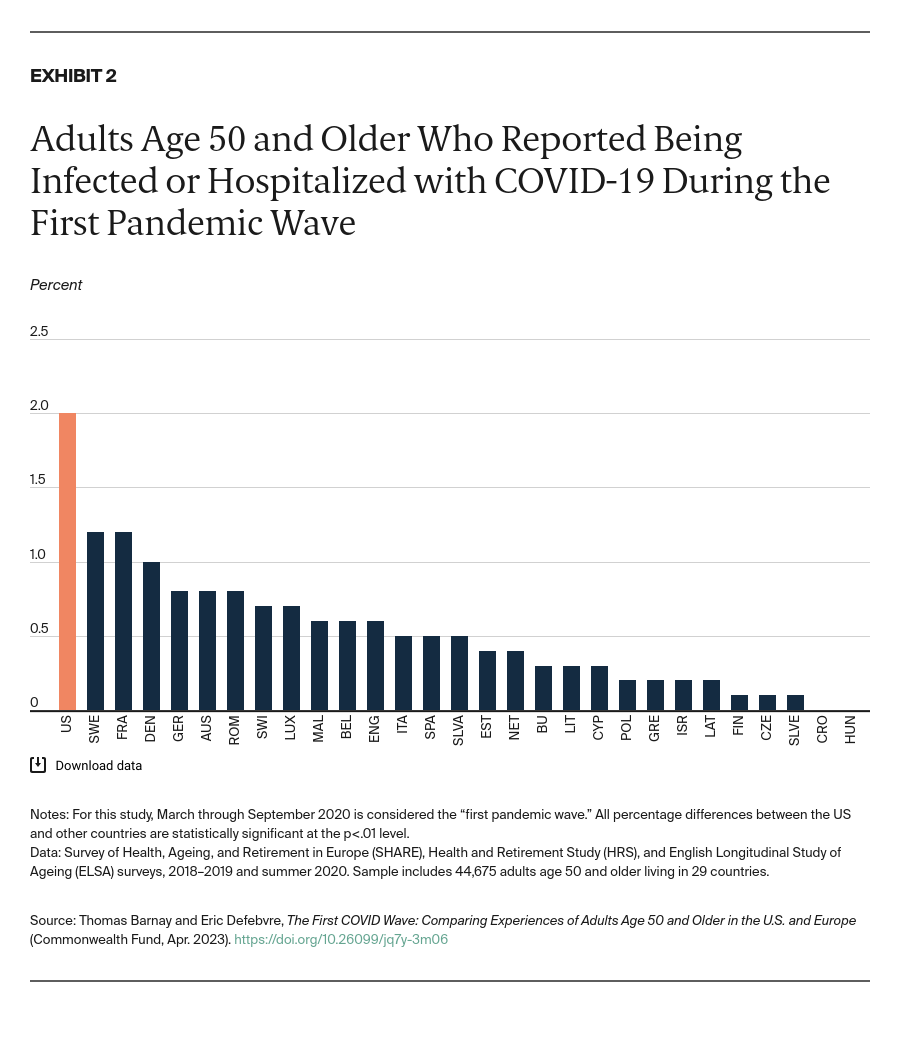

- Being infected or hospitalized with COVID-19: This includes older adults who reported testing positive for COVID-19 or being hospitalized because of the coronavirus.2 Even though these events may result in different health outcomes (e.g., those who are infected could be asymptomatic), we combined them to increase the sample size.

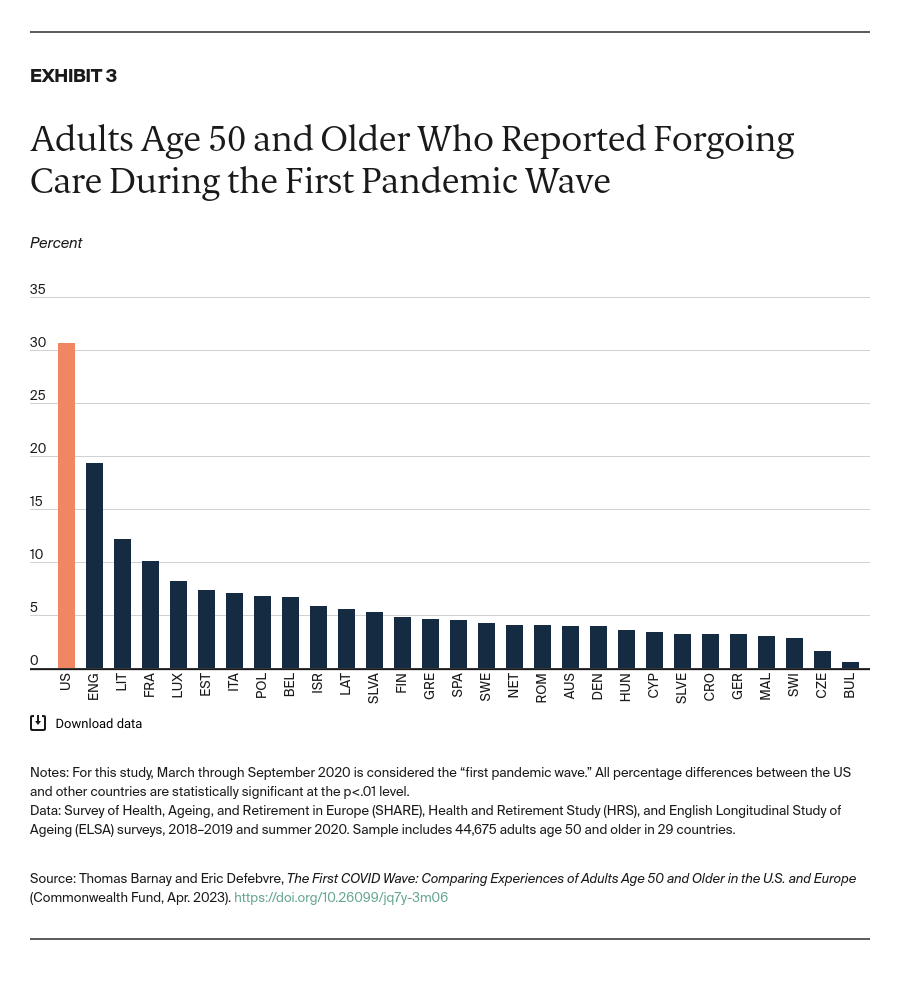

- Forgoing care: This includes older adults who reported that they needed medical or dental care but delayed getting it or did not get it at all; asked for an appointment for medical treatment and did not get one; or had a hospital operation or treatment cancelled or were unable to see or talk to a general practitioner.

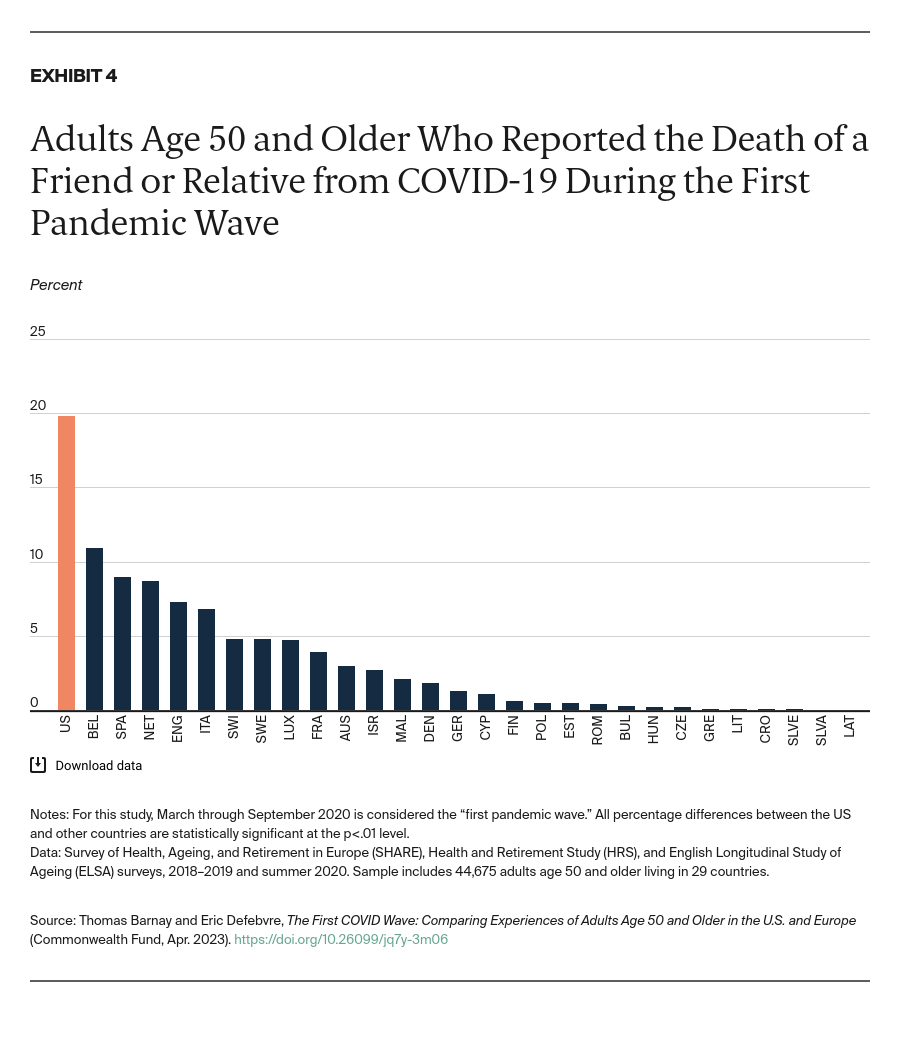

- Having a friend or relative die from COVID-19: This includes older adults who reported experiencing the death of someone they knew or someone close to them, such as a friend or family member.

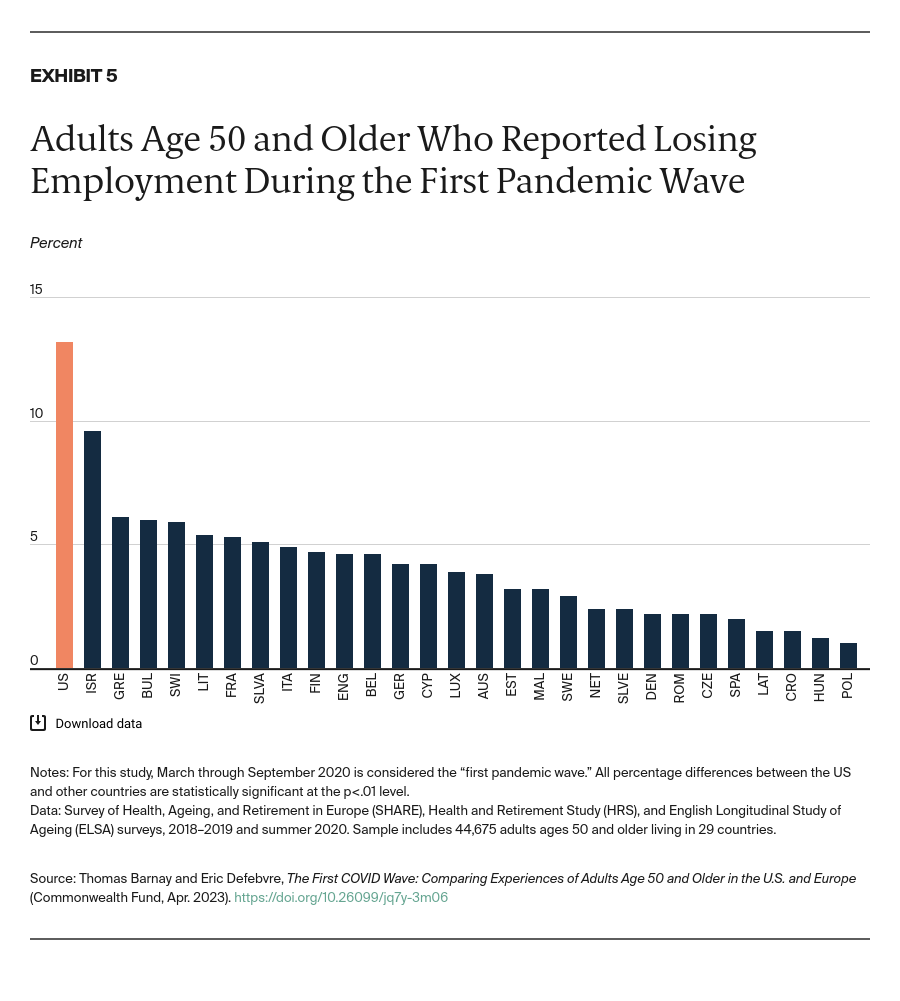

- Losing employment: This includes older adults who reported that they stopped working entirely because of losing their job, being furloughed, quitting, or for another reason; or became unemployed, were laid off, or had to close their business because of the coronavirus.

Key Findings

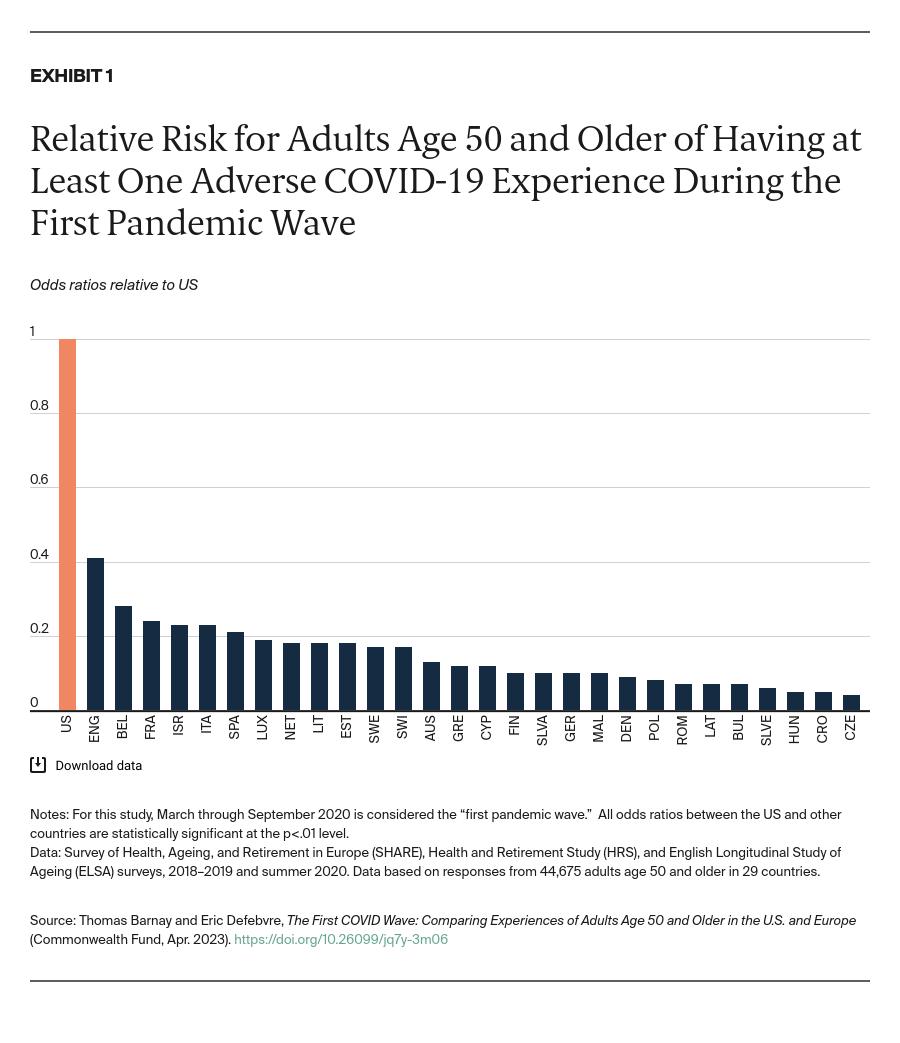

After calculating the relative risk (odds ratios relative to the U.S.) and controlling for age, gender, education level,3 and self-assessed health, we found that older adults in the U.S. were significantly more likely to report having at least one adverse COVID-19 experience, compared with their peers in all European countries (Exhibit 1).4