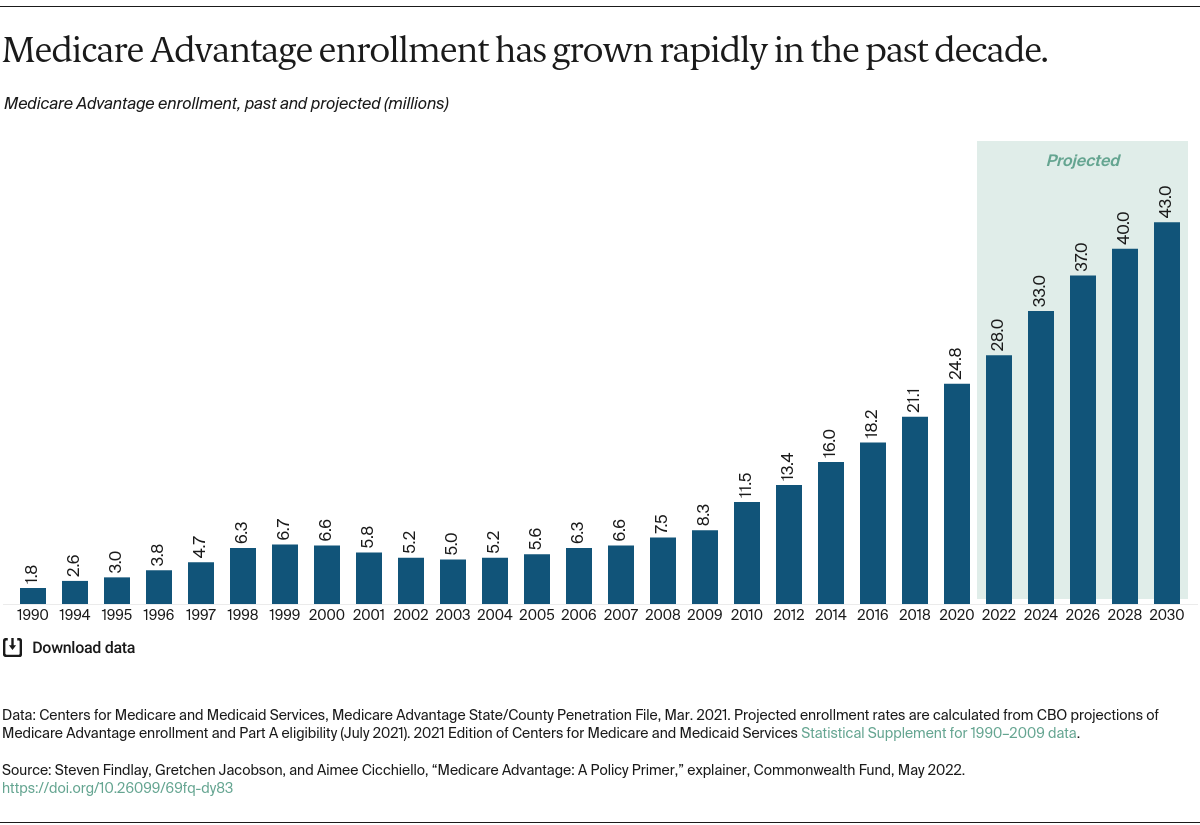

In 2023, 49 percent of Medicare beneficiaries were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans.2 By 2025, these plans are projected to account for over half of total Medicare enrollment — 35.4 million beneficiaries, up from 21.3 million in 2018.3

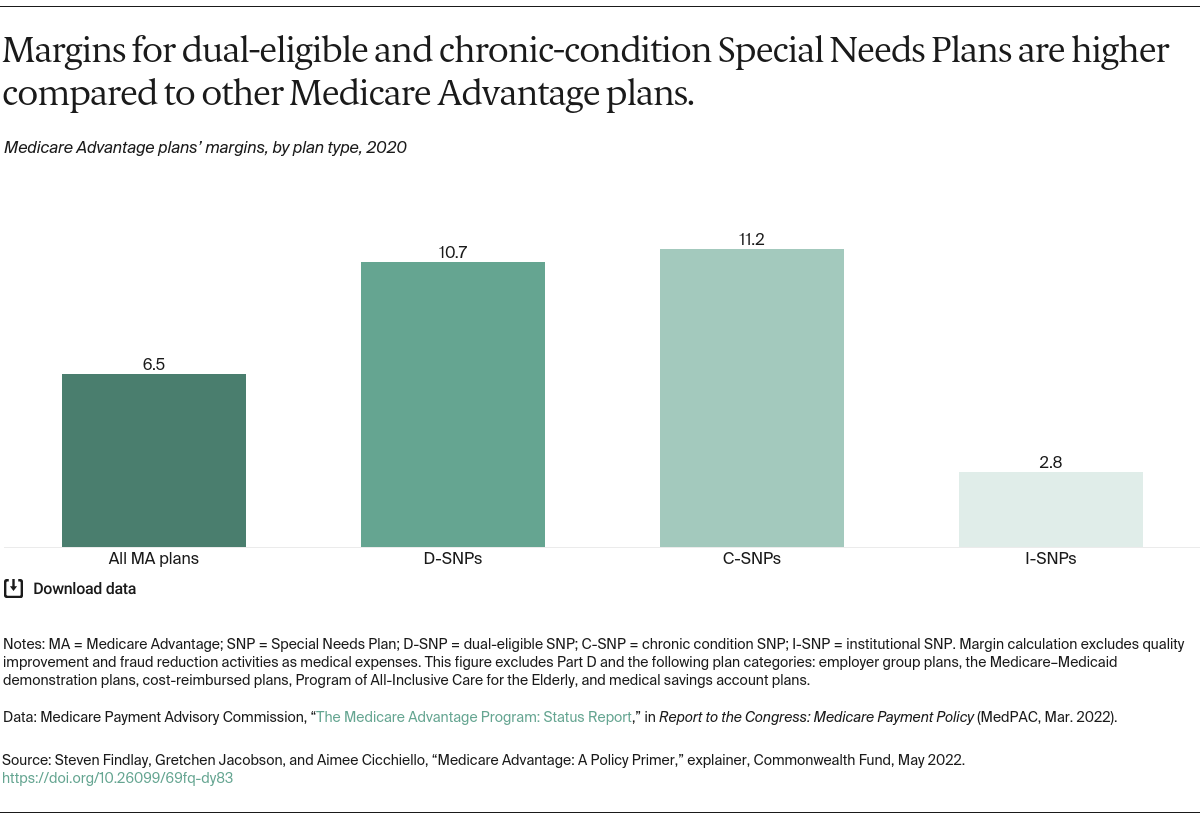

More than 6 million beneficiaries in 2023 were enrolled in Special Needs Plans, which are Medicare Advantage plans designed for people with high health care needs, including those who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, have specific chronic conditions, or require an institutional level of care. About 5.5 million beneficiaries were enrolled in Employer Group Plans, which are Medicare Advantage plans for employers’ retirees.

What are the differences between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage?

Access to providers. People with traditional Medicare have access to any doctor or hospital that accepts Medicare, anywhere in the United States. That’s the vast majority of doctors and virtually all hospitals.

In contrast, Medicare Advantage enrollees can access providers only through more limited provider networks. All Medicare Advantage plans are required to have such networks for doctors, hospitals, and other providers.

Provider participation in these networks can vary greatly. A 2017 analysis found that Medicare Advantage networks included fewer than half (46%) of all Medicare physicians in a given county, on average. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which administers Medicare Advantage plans, has stated that it will strengthen its oversight of plan networks starting in 2024, based in part on an analysis finding that some plans were not in compliance in recent years with “network adequacy” standards.

It’s not clear if broader or narrower networks equate to better or worse care. While many experts note that narrow-network plans can have more control over costs and quality of care, some Medicare Advantage plans tout their broader networks. Unfortunately, access to reliable information on plan networks is typically not easy for enrollees or their family members to obtain. That’s because provider directories are frequently out of date and formatted in ways that make it difficult to directly compare networks. Moreover, prospective enrollees may be less apt to compare networks for postacute care services like home health and skilled nursing care that they might not anticipate needing.

Managed care. Nearly all Medicare Advantage enrollees are required to obtain prior approval, or authorization, for coverage of some treatments or services — something generally not required in traditional Medicare. Plans that require prior authorization can approve or deny care based on medical research and standards of care. For services not subject to prior authorization, plans can deny coverage for care they deem unnecessary after the service is received, as long as they follow Medicare coverage rules and guidelines.

It’s long been a concern that such denials of care via prior authorization, or payment denials after care was delivered, were more widespread than Medicare Advantage plans claimed. A recent government report sheds light on this. It probed coverage denials during one week in June 2019 at 15 Medicare Advantage plans and found that 13 percent of denials were inappropriate and should have been covered under Medicare rules. That extrapolates to some 85,000 denials at those 15 plans for all of 2019. The study also probed payment denials, finding 18 percent were inappropriate and the care should have been paid for. That extrapolates to an estimated 1.5 million wrongful payment denials for all of 2019 at the 15 plans studied. These findings suggest an unacceptably high rate of inappropriate denials of care and payment by some Medicare Advantage plans. Yet, it’s important to balance the findings against the well-established and unacceptable level of inappropriate care delivered by providers in traditional Medicare. Both denials of care and inappropriate, unnecessary care can be harmful as well as costly.

Covered benefits. Medicare Advantage plans must cover all services covered by traditional Medicare under Part A (hospital services, some home health, hospice care, skilled nursing care) and Part B (physician services, durable medical equipment, outpatient drugs, mental health, ambulance services). The vast majority of plans (89% in 2024) also cover Part D prescription drug benefits. Most plans offer additional benefits such as eyeglasses, hearing aids, and some coverage of dental care, such as cleanings.4

In 2020, the government began allowing Medicare Advantage plans to include a wide range of telehealth benefits as part of their basic benefit package. Some plans also cover fitness club memberships, caregiver support, meal delivery, or acupuncture.

Traditional Medicare has notable gaps in coverage. For example, it does not cover eyeglasses, hearing aids, basic dental care, or long-term care. It also requires cost sharing for most services. Traditional Medicare also does not have prescription drug coverage, and beneficiaries must choose a separate “stand-alone” Part D plan if they want drug coverage. Part D coverage is offered entirely through private insurance plans; there is no government-run option.

Because of those gaps, many people with traditional Medicare buy Medigap or Medicare Supplemental coverage as well as Part D prescription drug coverage. Medigap plans cover many of the additional costs not covered by traditional Medicare — for instance, the 20 percent copayment for most routine Part B doctor’s services. Some Medigap plans also include services not covered by traditional Medicare, such as access to dental care or eyeglasses.

Medigap coverage is provided through private insurers. The premium that enrollees pay is in addition to the Medicare Part B premium and the Part D premium for those who choose to buy prescription coverage.

In most states, Medigap insurers are required to issue policies to any interested beneficiaries only during certain enrollment windows; at all other times, Medigap insurers can deny coverage or set premiums for policies based on health status (underwrite) of new policyholders. These limited enrollment windows are known as “guaranteed issue” rights. Medigap insurers are prohibited from selling policies to Medicare Advantage enrollees.

Out-of-pocket costs. Like other Medicare beneficiaries, Medicare Advantage enrollees must pay their Part B premium ($174.70 per month in 2024, with higher amounts for higher-income people). A small number of Medicare Advantage plans pay all or a portion of Part B premiums.

As mentioned, Medicare Advantage plans also can charge an additional monthly premium, which typically includes Part D prescription drug benefits. The average premium for a Medicare Advantage plan that includes Part D coverage in 2023 is $15 per month. Some plans cost nothing, while others can be $100 or more. Seventy-three percent of Medicare Advantage enrollees had no premium in 2023; about 7 percent paid $50 or more per month.

Since 2011, the government has required Medicare Advantage plans to limit enrollees’ out-of-pocket expenses for services covered by Parts A and B. In 2024, the maximum is $8,850 for in-network services (for HMOs, and for PPOs if only in-network services are used) and $13,300 for in-network and out-of-network services combined (for only PPOs, when out-of-network services are used).

Some Medicare Advantage plans compete for enrollees by offering a lower-than-required cap on out-of-pocket expenses for doctor and hospital services. In 2023, the average out-of-pocket limit was $4,835 for in-network services.5

Traditional Medicare has no out-of-pocket maximum for doctor or hospital service costs. As a consequence, most beneficiaries in traditional Medicare have Medigap, to make their out-of-pocket expenses more manageable and predictable, or another form of supplemental coverage, such as coverage from a former employer or Medicaid. In 2020, the average Medigap premium was about $138 per month; in 2024, the average total monthly premium for a Part D plan is $55.50.

Many factors influence whether a beneficiary would pay more with traditional Medicare or with a Medicare Advantage plan. Those factors include: health status and health care use; supplemental coverage and premiums for that coverage; Medicare Advantage plan benefits and cost sharing; and plan provider networks.

Quality of care. Most evidence shows that the quality of care delivered through Medicare Advantage plans and through traditional Medicare is equivalent overall. However, some studies suggest that Medicare Advantage plans, on average, are associated with better-quality care on certain metrics, particularly those related to preventive care and unnecessary hospital admissions.6 Other evidence suggests that Medicare Advantage does not outperform traditional Medicare on several significant measures, including mortality, readmission rates, patient experience, and racial and ethnic disparities.7

CMS rates Medicare Advantage plans based on more than 40 quality measures and uses a star rating system, with five stars the highest. In 2023, 71 percent of enrollees were in plans with an overall quality rating of four or more stars, down from 86 percent in 2022.8 This drop stemmed largely from the expiration of public health emergency–era measures that held plans harmless for lower performance on certain quality measures.

Some critics have raised questions about the star rating program and whether it’s appropriately incentivizing plans to meaningfully improve care — the program’s stated objective. In a 2021 report, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, or MedPAC, concluded that “the current quality program is not achieving its intended purposes and is costly to Medicare.”9

Do Medicare Advantage plans cost government and taxpayers less or more?

Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage can be compared in many ways, including benefits provided, quality of care, patient outcomes, and costs. Policymakers have focused mainly on comparing costs in traditional Medicare with those in Medicare Advantage, primarily because the original impetus for allowing private insurers to provide Medicare benefits was to reduce costs while maintaining or improving quality of care.

Older and more recent studies alike have largely found that Medicare Advantage plans cost the government and taxpayers more than traditional Medicare on a per beneficiary basis.10 In 2023, that additional cost was about 6 percent, down from a peak of 17 percent in 2009.11

Why do Medicare Advantage plans cost more, and how are they paid?

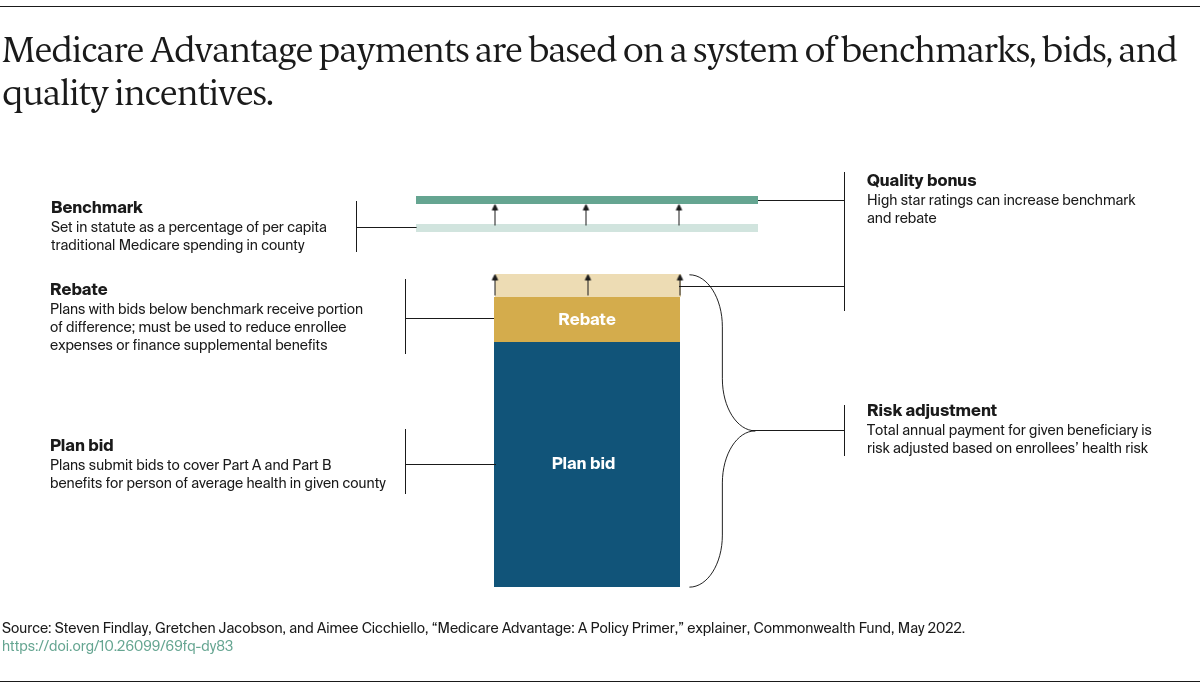

The government pays Medicare Advantage plans a set rate per person, per year (around $12,000 in 2019, not including Part D–related expenses) under what’s known as a risk-based contract.12 That means that each plan agrees to assume the full risk of providing all care for that inclusive amount. This payment arrangement, called capitation, is also intended to provide plans with flexibility to innovate and improve the delivery of care.

But there are layers of complexity built into and on top of that set rate that allow for various adjustments and bonus payments. While those adjustments have proved useful in some ways, they can also be problematic. They are the main reason why Medicare Advantage costs the government more than traditional Medicare for covering the same beneficiary.