In 2023, more than 650,000 people in the U.S. were homeless — the highest number since the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development started tracking these data. While 60 percent of people who are homeless live in shelters or transitional housing, the remaining 40 percent are unsheltered, meaning they live in places that aren’t considered suitable for human habitation, such as streets, abandoned buildings, or parks. People who are unsheltered tend to have significant health challenges; the health care system has historically failed to meet their needs.

Poor health is a driver of and a result of homelessness. The links between poverty and poor health are well established, and the living conditions that people who are homeless face can pose serious health risks or exacerbate existing health problems. Compared to people living in poverty who are housed, people experiencing any type of homelessness are 60 percent more likely to die in a given year. People who are unsheltered have unique health challenges, with disproportionately high rates of communicable diseases and chronic conditions such as behavioral health conditions, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and heart disease.

Accessing health care services is challenging for people who are unsheltered. Barriers include a lack of transportation or insurance, inability to pay for care, and limited access to technology or other resources to make or track appointments. Some people may avoid seeking care because of previous medical trauma or mistreatment or because their living situation requires them to prioritize immediate needs (e.g., finding their next meal) over health maintenance.

Street Medicine Brings Care Directly to People

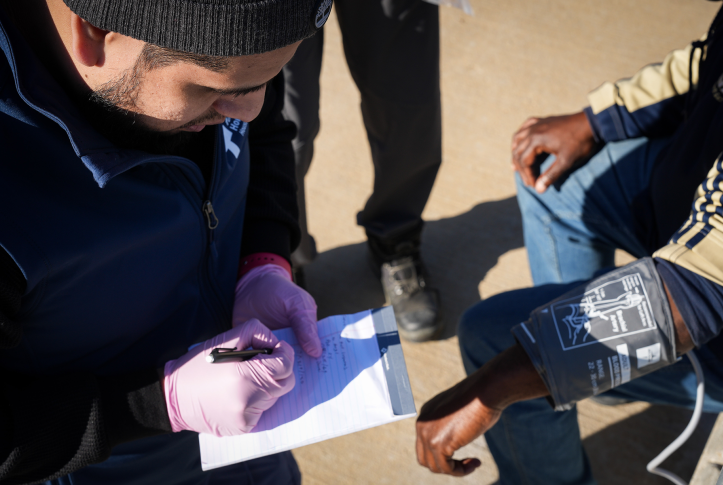

For decades, clinicians and other service providers have tried to meet the needs of people who are homeless by creating street medicine programs, which bring care directly to people in their current environments. This model allows providers to offer many services traditionally administered in clinics instead in a street setting. These can include prescribing and administering medication and vaccinations; labs, diagnostics, or point-of-care testing; and health education. Street medicine is also a promising approach for expanding access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment.

Relationship-building is central to success. That means delivering care where and when people feel comfortable, letting patients define their goals for care, and listening to their priorities. Street medicine uses a team-based model, which typically includes at least one medical provider paired with an outreach worker like a community health worker. Outreach workers establish relationships with people and connect them with resources to meet nonmedical needs, such as referrals to transitional housing or nutrition assistance programs.

A New Option: Paying for Street Medicine with Medicaid

Street medicine started as a grassroots movement but has become increasingly organized, with more than 150 programs nationwide. However, many programs rely on grants or volunteers and have been limited by a lack of funding.

Until recently, street medicine providers in most states (except California and Hawaii) could not bill public insurance programs because there was no federal billing code for care provided in street settings. In October 2023, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services added a place of service (POS) code to allow Medicare and Medicaid providers to bill for these services. The addition of the POS code could significantly expand street medicine’s reach, particularly because of its potential to unlock funding through Medicaid. Many people who are homeless — particularly those living in states that have expanded eligibility under the Affordable Care Act — are eligible for Medicaid because of their low income.

How State Medicaid Programs Can Support Street Medicine

The new POS code for street medicine is a first step, but more work is needed to support the expansion of street medicine in Medicaid. State policymakers should consider the following actions:

- Educate providers about the POS code and offer technical assistance to street medicine providers interested in billing Medicaid. Billing Medicaid can be administratively burdensome; street medicine providers may need guidance on how to set up the necessary data collection and reporting systems.

- Encourage more Medicaid managed care organizations to include street medicine providers in their provider networks.

- Issue policies and guidance for billing the various provider types included in street medicine teams, including nonclinical providers like community health workers.

- Ensure sufficient payment rates for street medicine services. Providers in states that are already paying for street medicine via Medicaid have called for higher payment rates that more accurately reflect the cost of delivering services.

- Make it easier for people who are homeless to enroll in and maintain Medicaid coverage. Research suggests that a significant portion of people who are homeless and qualify for Medicaid are not enrolled, likely because of barriers to obtaining coverage, like not knowing they qualify, not knowing how to apply, finding the application process too complicated, or lacking access to the resources they need to enroll. While street medicine outreach workers can address some of these challenges, states can also make enrollment and renewal processes easier. For example, Massachusetts is using an 1115 waiver to provide older adults experiencing homelessness with 24 months of continuous Medicaid eligibility.

As states grapple with increases in homelessness, many are leveraging their Medicaid program and managed care contracts to connect people to housing. Financing street medicine through Medicaid is one piece of the puzzle to address health needs and connect people to the resources they need to become stably housed.