After a two-and-a-half-year lull in which no state took up the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) provision to expand Medicaid eligibility to more Americans living in poverty, 2019 has already ushered in an expansion in Virginia. And as many as six more states are waiting in the wings. In November, voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah overwhelmingly approved state ballot initiatives to expand Medicaid. And in January, new governors supportive of expansion took office in Kansas and Wisconsin. The prospect of Medicaid expansion in these five states plus Maine, where implementation is finally under way following a 2017 ballot referendum, means that as many as 300,000 uninsured Americans may gain coverage this year.

But concerns about the cost of expanding eligibility for Medicaid have been a roadblock to implementation in these states, along with the dozen others that have yet to expand the program. Here, we look at the cost to states of expanding eligibility for Medicaid, and what expansion means in practice for state budgets.

The Federal Government Pays 90 Percent of the Total Cost of Medicaid Expansion

Beginning in 2014, the ACA offered states the option to expand eligibility for Medicaid to individuals with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or roughly $17,000 per year for a single person. (Previously, the federal government required Medicaid be available only to children, parents, people with disabilities, and some people over age 65, and gave states considerable discretion at setting income eligibility levels.) While Medicaid is a jointly funded partnership between the federal government and the states, the ACA provided 100 percent federal funding to cover the costs of newly eligible enrollees until the end of 2016 in states that took up the expansion. The federal government currently pays 93 percent of the total costs, and this year alone will provide an estimated $62 billion to fund expansion, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

In 2020, the federal share will drop to 90 percent where, barring a change to the law, it will stay. This leaves states on the hook for at most 10 percent of the total cost of enrollees in the new eligibility category — considerably less than the roughly 25 percent to 50 percent of the cost that states pay for enrollees eligible for Medicaid under pre-ACA criteria.

States Realize Savings from Expansion

Opponents of Medicaid expansion in states that have yet to implement it worry that even a 10 percent contribution to the cost of extending Medicaid coverage to more people will result in a large increase in state spending. But the experience of a long list of states suggests otherwise. That’s because expansion allows states to realize savings by moving adults who are in existing state-funded health programs into expansion coverage. Expansion also allows states to reduce their spending on uncompensated care as uninsured people gain coverage.

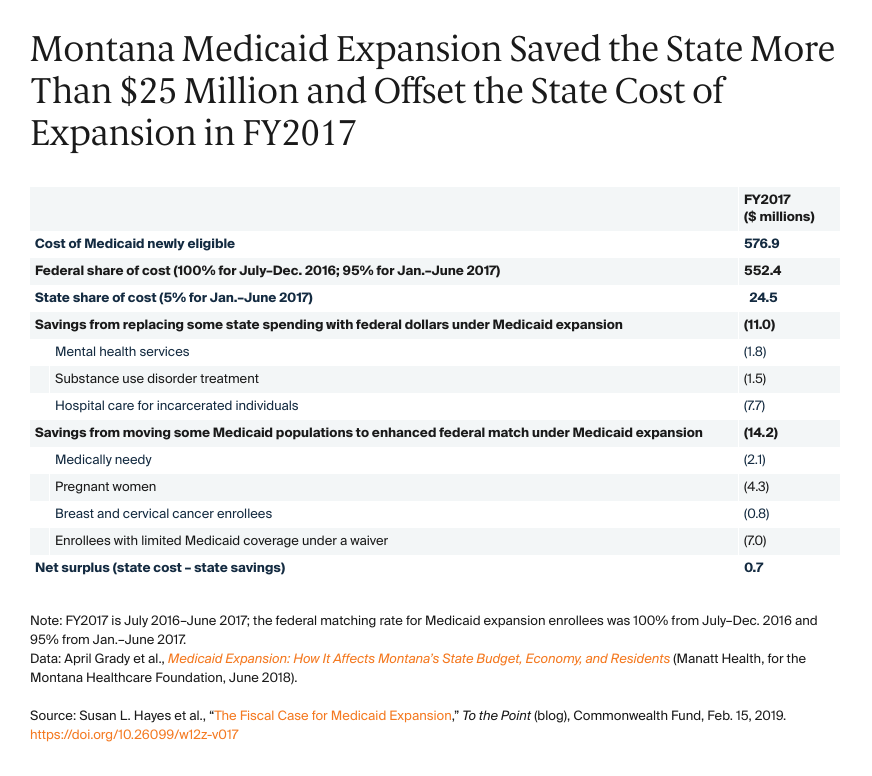

The table below offers a snapshot of what this looked like in Montana, where Medicaid expansion took effect in January 2016. In FY2017, the total cost of Medicaid expansion was $576.9 million. Because the federal match was 95 percent to 100 percent during this time, the state’s share was $24.5 million. But the state then experienced a series of offsets, or savings it realized from not spending money on separate health-related programs fully funded by the state, such as substance use disorder programs. The state also realized savings when some groups who were previously covered under existing Medicaid were moved to the expansion population, which has a higher federal matching rate. Taken together, these offsets added up to $25.2 million, leaving Montana with a surplus of $700,000 in FY2017. One study found that Arkansas and Kentucky amassed enough surplus because of offsets during the first two years of expansion, when the federal government was footing the entire bill, to cover the costs of expansion through FY2021.

Net Costs Are a Minuscule Portion of States’ Overall Budgets

It’s also worth noting that even if Montana had been responsible for 10 percent of the total cost in FY2017, or $57.7 million, after offsets were applied, the net cost to the state — or the amount it actually spent on Medicaid expansion — would have been $32.5 million, only about 1 percent of Montana’s general fund expenditures of $236.5 billion in FY2017. In Nebraska1 and in Kansas, two of the states that may be among the next to implement expansion, estimates have shown that the state cost after offsets is less than 1 percent of the general fund.

Paying the Balance

Of the 32 states that, along with the District of Columbia, have implemented Medicaid expansion, nine are using taxes — on cigarettes; alcohol; or hospital, provider, or health plan fees — to help pay for it. The ballot initiative approved by voters in Utah in November increased the state’s sales tax by 0.15 percent with the requirement that the new revenue be used to pay for the cost of expansion there. (Even so, earlier this week, Utah Governor Gary Herbert signed into law a bill approved by the Republican-led legislature that will scale back the full Medicaid expansion that voters approved.)

States that expand Medicaid also realize economic benefits beyond increased federal funds. For example, a Commonwealth Fund-supported study found that as a result of new economic activity associated with Medicaid expansion in Michigan, including the creation of 30,000 new jobs mostly outside the health sector, state tax revenues are projected to increase $148 million to $153 million a year from FY2019 through FY2021.

A U.S. Senate bill cosponsored by Senator Doug Jones (D–Ala.), who has advocated for his state to adopt expansion, could help reassure states skittish about expanding because of the impact on their budget. The legislation would grant states, regardless of when they adopt expansion, the same levels of federal matching funds that states that expanded the program in 2014 received (100% federal funding for the first three years, phasing down over three more years to 90%).

Indeed, a national study confirmed that during the two years when the federal government paid all of the costs for newly eligible enrollees, Medicaid expansion did not lead to any significant increases in state spending on Medicaid or to reductions in spending on other priorities such as education. But even at a lesser percent match, the fiscal case for expansion is compelling.

A future To the Point post will examine the broader economic benefits associated with Medicaid expansion.