Abstract

- Issue: The Affordable Care Act (ACA) includes a “firewall” provision that prohibits workers with an affordable offer of employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) from receiving premium tax credits in the individual insurance marketplace. Eliminating the firewall could help certain low-income workers find more affordable coverage options in the marketplace.

- Goals: Simulate the effects of removing the firewall on health insurance coverage, household premiums, and overall costs to federal and state governments.

- Methods: We use the Urban Institute’s Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model to estimate the effects of firewall removal.

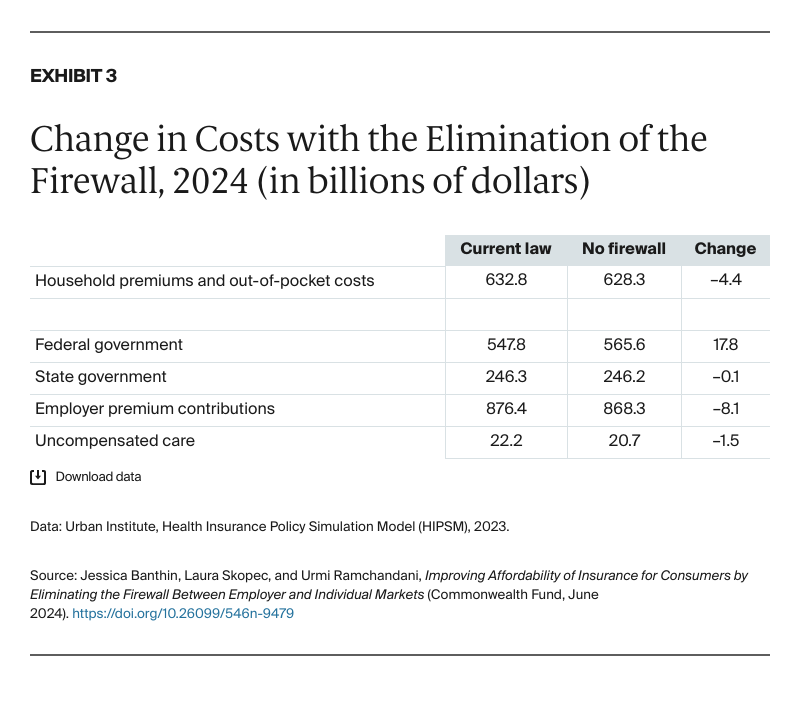

- Key Findings and Conclusion: Eliminating the firewall leads to 1.8 million people (1.2%) shifting out of ESI, with many finding more affordable coverage in the marketplace (and a few in Medicaid) and a reduction of 1.4 million uninsured people. However, the tax subsidies for ESI are large enough that most of those with ESI benefit by staying enrolled in that coverage. Removing the firewall would save households $4.4 billion in premiums and other health care spending. The federal government would increase spending by $17.8 billion, primarily for marketplace premium tax credits. This would represent an increase of 18 percent in federal spending on premium tax credits.

Introduction

The U.S. tax system is structured to enhance the affordability of private health insurance coverage through tax-based subsidies. In 2022, about 156 million people with employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) benefited from excluding the cost of ESI from their taxable compensation.1 Additionally, approximately 13.5 million people were enrolled in subsidized nongroup coverage through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) health insurance marketplaces, available to those without access to an affordable offer of ESI.2 For 2022, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the federal government spent $316 billion on ESI tax subsidies and $89 billion on marketplace subsidies.3 The generosity of these subsidies varies between the individual and employer markets and by income.

The ESI tax exclusion effectively offers larger subsidies to those in higher tax brackets, as the marginal tax rate they would have to pay if health insurance coverage were taxed is higher. The tax exclusion is also proportional to the cost of coverage: the higher the cost of coverage, the larger the amount excluded. For that reason, the tax exclusion encourages many employers to offer more comprehensive benefits and wider provider networks that increase the cost of coverage. However, not all employers offer generous coverage. A small share of employees are offered plans that meet the minimum value required by law: a plan that covers just 60 percent of expected costs, although the exact number of employees with such plans is uncertain.4

The ACA’s marketplace premium tax credits (PTCs) work in the opposite manner to the ESI tax exclusion, offering larger premium subsidies to enrollees with lower incomes. Moreover, enrollees with incomes below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) are also eligible for cost-sharing reductions that substantially increase the generosity of the coverage; available plans may cover 94 percent, 87 percent, or 73 percent of expected costs. Additionally, expected employee contributions in ESI are set by individual employers, but the marketplaces offer standardized, income-based subsidies, with enrollee contributions set by formula. Depending on the expected employee contribution for ESI, some low-income employees may be able to purchase similar or better coverage in the marketplace for lower out-of-pocket premiums than in ESI.

How the Firewall Limits Access to Premium Tax Credits and More Affordable Coverage

The ACA includes a “firewall” provision that prevents workers from receiving PTCs and cost-sharing subsidies in the marketplace if they had an affordable offer of ESI. This provision was intended to keep the employment-based system intact. Under the ACA, ESI is considered affordable if the employee’s premium contribution is less than 8.39 percent of household income in 2024.5 However, many lower-income workers could access more affordable coverage via the marketplaces, where premiums are limited to up to 8.5 percent of household income under current law.6

Employees with household income less than 150 percent of FPL would be eligible for $0 premium silver plans with generous cost-sharing reductions on the marketplace if the firewall were removed, and employees with household income at 200 percent of FPL would pay a premium of 2 percent of income for a silver plan with additional cost-sharing reductions.7 Right now, these lower-income employees cannot access marketplace coverage if their employer offers affordable ESI, even if marketplace coverage would be less expensive or more comprehensive. For example, in 2023, a single worker with income of $25,000 (172% of FPL) would pay $220 (0.9% of income) for the entire year for marketplace coverage after receiving a PTC. But an ESI offer requiring the worker to pay $2,250 (9% of income) for coverage would trigger the firewall and disqualify the worker from receiving any PTC.

Some workers with an ESI offer that is deemed affordable under the ACA remain uninsured because of the firewall policy. Dropping the firewall could allow these adults to access marketplace coverage with PTCs. Additionally, some people who are barred from receiving PTCs by the firewall policy choose to pay full price for a private nongroup plan rather than enroll in ESI. If the firewall were eliminated, these people could also access PTCs and reduce their out-of-pocket premium costs.

Removing the firewall goes further than recent administrative changes to Internal Revenue Service (IRS) regulations that eliminated the “family glitch.” Prior to those changes, entire families were barred from marketplace subsidies if one family member’s employer offered an affordable individual-level plan.8 The IRS now has an affordability test for family coverage that allows dependents to receive marketplace subsidies if an employer offer of family coverage exceeds 8.39 percent of their household income in 2024.9 However, the employee may still be barred from marketplace subsidies if individual ESI coverage is considered affordable, and dependents may still be barred if family ESI coverage is considered affordable. Getting rid of the firewall opens access to marketplace subsidies and prevents families from having to enroll in separate plans.

Eliminating the Firewall Would Allow Some Lower-Income Employees to Attain Generous Coverage

Many employers offer comprehensive ESI coverage with low deductibles and copayments that is comparable to gold or platinum plans available in the marketplace in terms of actuarial value.10 However, not all employers offer such benefits, and evidence suggests the generosity of ESI has been eroding over time.11 In contrast, marketplace plan premium tax credits and plan generosity are defined by law. Therefore, some low-income employees whose employers offer less generous coverage with high employee premium contributions may be able to find more generous coverage for a lower cost on the marketplace if the firewall were removed.

This brief estimates the effects of dropping the firewall on health insurance coverage and spending by households, states, and the federal government. We assess changes in coverage and household spending by income. We also conduct sensitivity analyses lowering the affordability threshold for ESI to 4 percent of family income, since some policymakers have advocated a reduction in the threshold as an alternative to the complete elimination of the firewall.12 (For more details, see “How We Conducted This Study.”)

Coverage and Cost Impact of Eliminating the Firewall

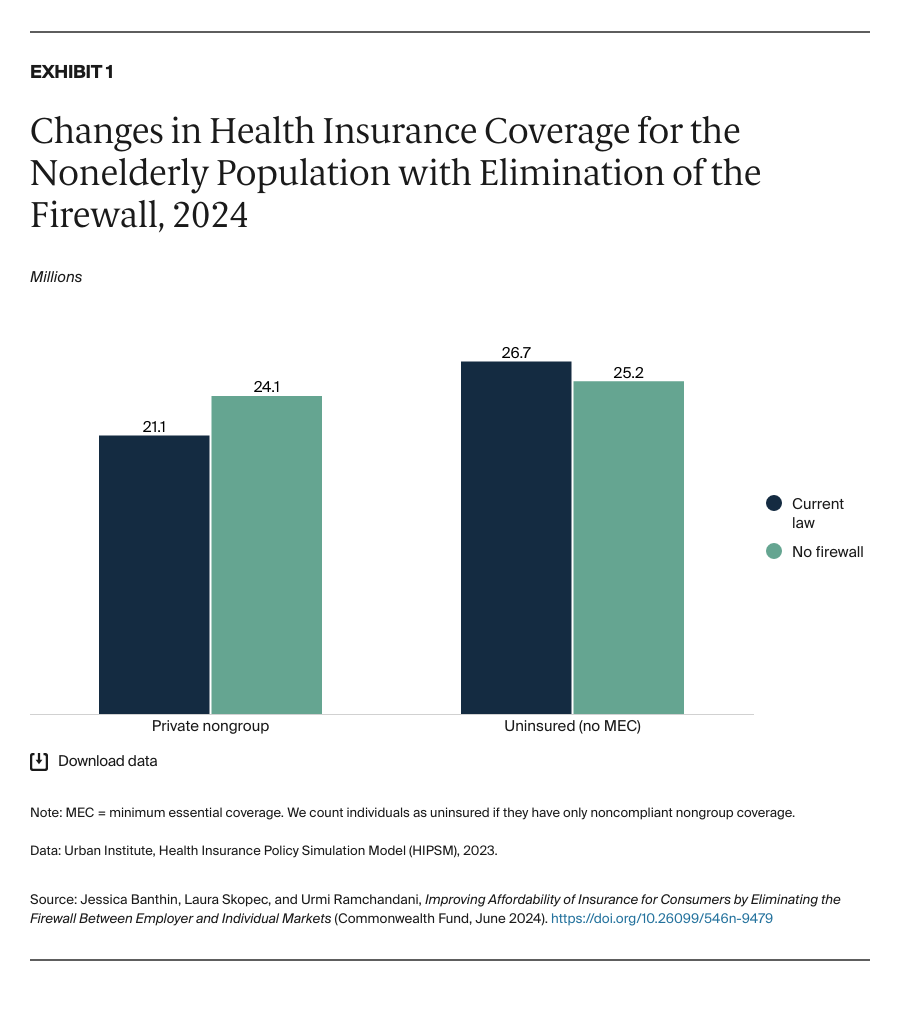

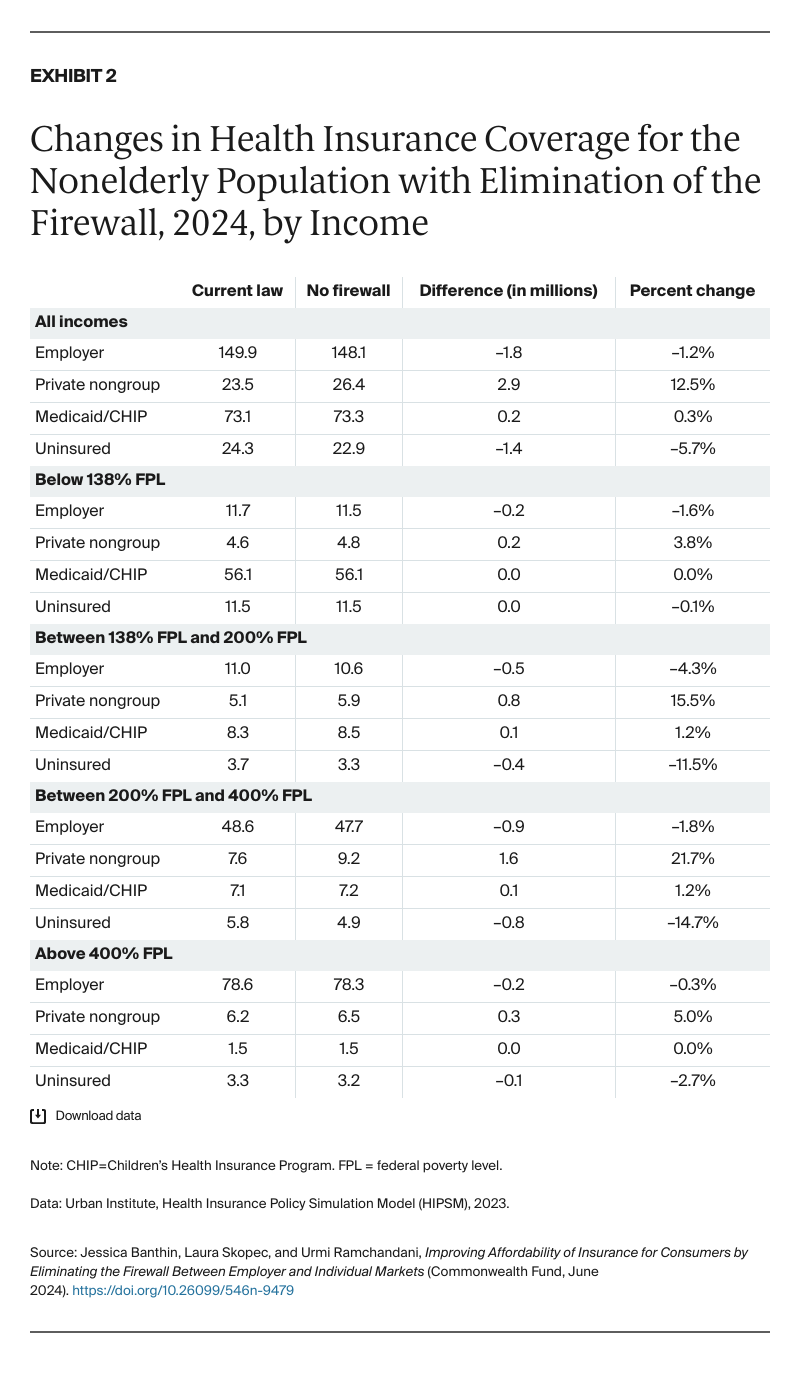

If the firewall policy were eliminated in 2024, ESI coverage would fall from 149.9 million to 148.1 million, meaning 1.8 million individuals under age 65 would drop or lose ESI (Exhibit 2). This loss of ESI would be offset by 2.9 million people gaining private nongroup coverage, primarily through the marketplace. About 0.2 million people, mostly children, would gain coverage through Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) when family members enrolled in the marketplace. Overall, 1.4 million fewer people would be uninsured. ESI coverage would fall by 1.2 percent, private nongroup coverage would increase 12.5 percent, and the number of uninsured would decrease by 5.7 percent (Exhibit 2).