The Commonwealth Fund Health Care Affordability Survey, fielded for the first time in 2023, asked U.S. adults with health insurance, and those without, about their ability to afford their health care — whether costs prevented them from getting care, whether provider bills left them with medical debt, and how these problems affected their lives.

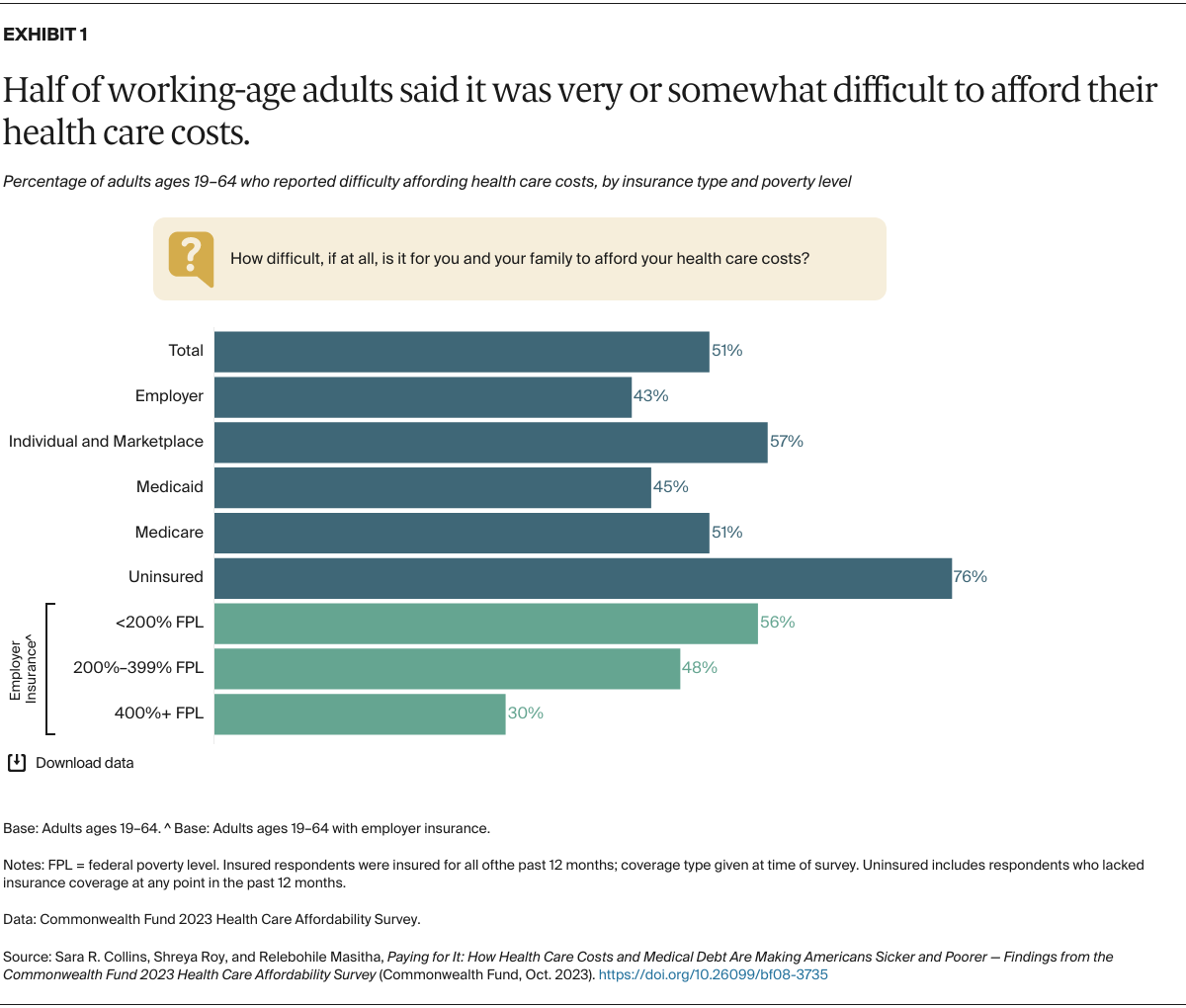

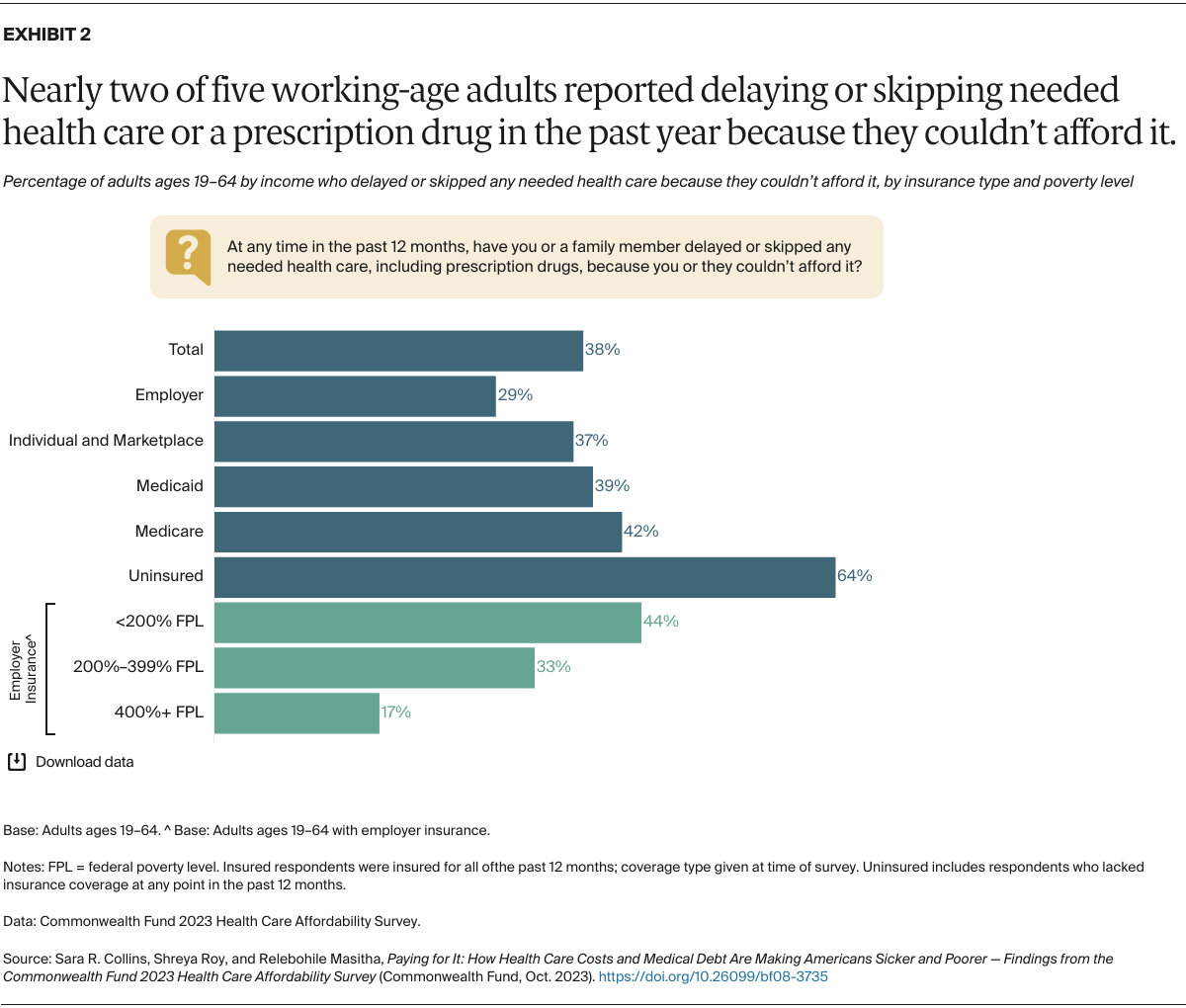

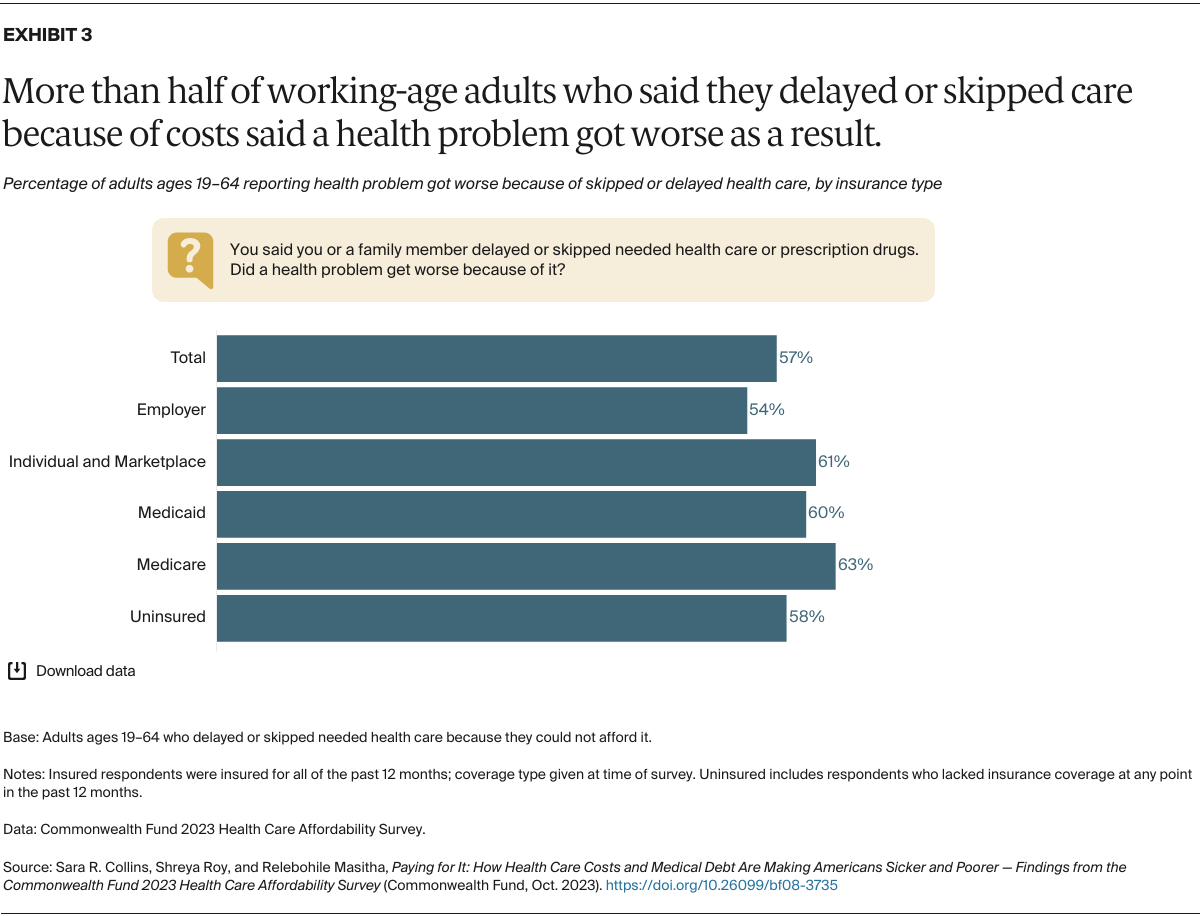

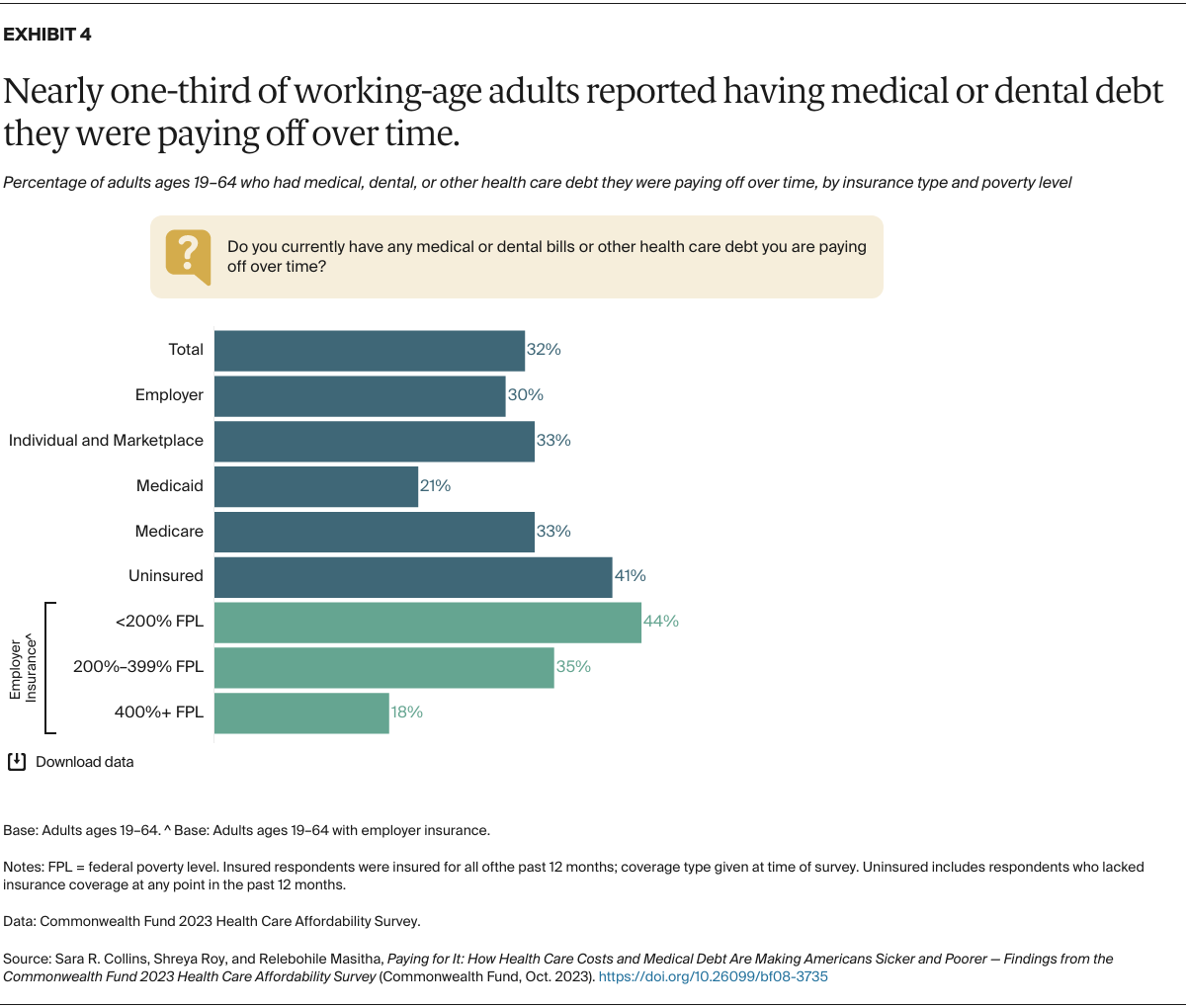

As the responses show, many Americans, regardless of where their insurance comes from, have inadequate coverage that’s led to delayed or forgone care, significant medical debt, and worsening health problems. While having health insurance is always better than not having it, the survey findings challenge the implicit assumption that health insurance in the United States buys affordable access to care. Difficulties affording care are experienced by people in employer, marketplace, and individual-market plans as well as people enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare.

In this brief, we present findings for survey respondents who were insured for the full year and those who spent all or part of the year uninsured. People who were insured all year are grouped by the coverage source they reported at the time of the survey, though it should be noted that some may have switched insurance during the year.

For the survey, SSRS interviewed a nationally representative sample of 7,873 adults age 19 and older between April 18 and July 31, 2023. Our analysis focuses on 6,121 respondents of working age, those 19 to 64. To learn more about the survey, see “How We Conducted This Survey.”