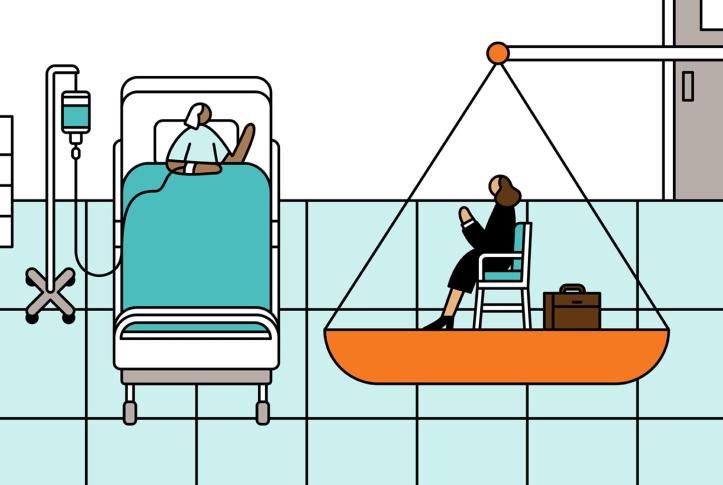

Getting and staying healthy depends on more than just medical care. In some instances, a patient also needs legal services. What if doctors could “refer” their patients to lawyers for help in dealing with a housing dispute, immigration status, or any number of legal issues?

On the latest episode of The Dose, we hear from Norma Tinubu and Emily Foote about how attorneys from the New York Legal Assistance Group work with health care providers at NYC Health + Hospitals, the largest public health care system in the U.S.

Through this medical-legal partnership, some of the city’s poorest patients can get the support they need to resolve legal problems that, if ignored, could take a toll on their health.

Transcript

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Hey Dose listeners, in this episode you won’t hear us talk about COVID-19 because we recorded it in February, before the pandemic disrupted all our lives. What you will hear us talk about is public charge, a Trump administration rule that says, “If an immigrant uses public services, like health care, it may be more difficult for them to apply for a green card or U.S. citizenship in the future.” What’s changed?

On March 27th, U.S. Customs and Immigration Services said that immigrants with COVID-19 symptoms should get testing and treatment. Seeking this medical care would not be used against them under the public charge rule, but the rule is still in place, which means the fear it causes among immigrants — and we’ll talk more about that — is still a real problem.

We’re airing this episode today because right now we’re all confused and scared about our health, but for many people this year was just a way of life even before the pandemic. Here’s the show.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Hi, everyone. Welcome to The Dose. On today’s episode, we’re going to talk about what happens when a lawyer, so needing legal help, becomes a standard part of someone’s health care. Now, worries about immigration, housing disputes, domestic violence — these are some of the common legal issues that people usually need to see a lawyer for. When they go unresolved, they can actually make it really difficult for someone to get healthy or to stay healthy.

Some hospitals work with legal aid organizations and form medical-legal partnerships. Today we’re going to be talking about one of the oldest ones in the United States. This is between the New York City Health and Hospital System, which is the largest public health care system in the U.S., and New York Legal Assistance Group, or NYLAG, which provides free legal support to people living in poverty.

My guests are Norma Tinubu, who is an attorney with NYLAG, and Emily Foote, who works in the Office of Population Health at New York City Health and Hospitals. Norma, Emily, thanks for joining me.

EMILY FOOTE: Thank you for having us. We’re happy to be here.

NORMA TINUBU: It’s great to be here. Thanks.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: To get us started, Emily, tell me about the medical-legal partnership at Health and Hospitals. How does it work?

EMILY FOOTE: The medical-legal partnership that Health and Hospitals has with NYLAG’s legal health division is based on the very simple and practical concept that doctors, and nurses, and social workers, and lawyers working together can do more to help a patient or a family than any one of them can alone.

For my team, whose work focuses largely on the social determinants of health and elevating social needs of patients at H and H to the same level as medical needs.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: That’s like food, housing . . .

EMILY FOOTE: Exactly. It’s the social determinants of health are defined as the conditions in which people eat, work, live, play, worship. They’re made up of sort of concrete social needs like food, and housing, and income, and in this case legal services, which also get at indirectly or directly, many of the other social needs through advocacy.

This partnership for us really represents a cornerstone in our strategy for addressing social determinants of health, because it allows for solutions at this individual and family level practical solutions and interventions that help people with these individuals circumstances.

We hope ultimately that one of these interventions might interrupt the cycle of poverty in which many of our patients find themselves; not every referral can do that. Equally as important as the individual work is the upstream policy advocacy and what we think of as systems engineering.

This partnership, again, is so critical because the frontline work of this sort of really extended care team — the doctor, and the social worker, and the attorney working together — they can draw from very real-life patient stories and cases to inform policy advocacy. Whether it’s at the city, the state, the federal level in the media. Telling important stories that need to be told based in really profound fact. This work enables us to do that together with our senior Health and Hospitals leadership, along with NYLAG senior leadership, and other community organizations partnering together to do really strong advocacy work.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: I’d like to talk more about how the changes to our current immigration system under this administration might be affecting your clients. Are you seeing more people seeking asylum or a larger volume of cases?

NORMA TINUBU: Yeah, so we are seeing a larger volume of cases. A lot of it is really driven by fear. A lot of people are fearful of the current administration, the rhetoric coming out of the executive branch, all of the changes that have occurred.

One of the main changes being implemented is a new public charge rule being implemented on the 24th of February. We are seeing a volume of patients from the hospitals who need to file their cases before then, so that they are able to regularize their status and become lawful permanent residents under more current and relaxed rules.

The new rules will prevent people from becoming lawful in the U.S. for a variety of reasons that were never considered before. People with certain health conditions, people who have certain income levels, people who’ve received public benefits that were never before considered are now probably in danger of not being able to regularize their status because of their circumstances.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: The idea of public charge literally means that a person who is applying for permanent resident or citizenship status in the U.S. is deemed to be a charge or drain on public resources. So, that is actually jeopardizing their immigration status.

NORMA TINUBU: Exactly, or their ability to change and become legal. It’s really addressed that people who are applying to become legal, applying for a green card, not really citizens. It’s addressed to people who are applying to become green card holders and people who are seeking to come to the U.S. or remain in the U.S. as visitors. It’s being applied to really those two groups for the most part. It really could prevent many, many people — especially people who are vulnerable — populations from remaining in the U.S. on a permanent basis.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: What actually sounds more complicated is that the patients at Health and Hospitals are already very vulnerable and are already dealing with perhaps living in poverty. They have a health condition, obviously, that’s why they’re in the health system. Now they have to worry about their immigration status as well.

NORMA TINUBU: Exactly. So this is what’s driving the work right now. We are so busy trying to make sure that people are going to be eligible to live permanently in the U.S., receive a green card, and remain reunited with their families in the United States. So that we’re driven to at least file everything before the 24th of February, before this deadline.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: What are some of the other legal issues you work with? Obviously, it sounds like immigration is taking up the bulk of your attention right now?

NORMA TINUBU: Yes, right now we have a lot of immigration going on. We always had, it’s a pretty large part of our practice, but we do also housing. We help people with events planning, wills, health care proxies, and other advance directives. We also help people with guardianships. Right now, a lot of immigrants who are worried about the possibility of deportation under this administration now have the ability to appoint people who might be caretakers for their children in the event that they are deported or detained by the Immigration Service. We help people with various forms of government benefits.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Could you give me an example of a housing issue that you would typically see?

NORMA TINUBU: A lot of the housing cases we see involve housing condition issues. We do see a lot of people across the hospital come to us with housing problems. Maybe they have a leak that’s not being addressed and there’s mold growing in the apartment or the house where they’re living with their families and their young children, or they have other really serious housing conditions like pest control issues.

What the attorney at the clinic would do, after a referral by their doctor, is contact the landlords or the superintendent and really outline what the problems are, what their legal obligation to the tenant is, and ask them to fix the problem.

We do have a high rate of success in doing that. I can recall a case where the client had a baby from pediatrics, referred by pediatrics, whose body was covered with bruises and bumps, because I think he was being bitten by pests in the apartment.

We contacted the landlord after sending a letter and spoke to him about the problems and explained to him that he really needs to address them, he immediately needs to fix them. I think landlord was very surprised to get this call and promised to fix things as soon as possible. As a matter of fact, he was in the process of speaking to the contractors at the moment, at the time of the call, who were in the process of fixing and addressing some of the issues that we put in our letter to him.

I think about two weeks later we followed up with this patient and she was able to tell us that the problems were addressed and that she was happier in the apartment and that her child was more comfortable. That I think was a relief for the doctor, for the patient, and for us that we didn’t have to take it further.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: I think I remember, Norma, when we first talked that you had a story about a woman who was pregnant and was not on Medicaid, but you helped her to establish Medicaid eligibility.

NORMA TINUBU: Yes. This patient came to us at one of our H and H clinics from a referral through the OB/GYN unit. She was eligible for Medicaid but was refusing to accept coverage despite the fact that she’s pregnant and New York State does cover Medicaid for pregnant women, even though they’re undocumented. She was undocumented at the time and steadily refusing care because of the chilling factor of the new rules and the rhetoric of the current administration.

Her doctor called us and asked us to explain to her what the new rules would be about. Also, to apprise of her rights and just give her a very thorough legal consult. When we met with her, we were able to connect with her, explain what the rules were, sort of demystify what is going on with the changes in immigration and how they would not really impact her. Give her a really a thorough consult and also promise to assist her in legalizing her status because we identified that she was someone that we could help legalize status. She finally agreed to enroll in benefits after the consult. I think that was a pretty impactful appointment that we had.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: I mean, again, thinking about it and just hearing you tell the story again, this is a woman who’s pregnant and she is in a position where she’s thinking about her own health and the health of her child on one side, and then her legal status on the other side. With imperfect information, she was making a choice was actually jeopardizing her health and —

NORMA TINUBU: Exactly, and I think the doctor reached out to us, especially because she was someone with a high-risk pregnancy and really needed to be in care. She was steadily refusing because she was so worried about her immigration status and the impact of these new public charge rules and how they could possibly prevent her from legalizing status.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: If you had a patient who, for example, maybe they’re stuck in the waiting room, is there a way for an attorney to go out and meet them there? How do you make sure that— I guess what I’m trying to imagine is patients, particularly somebody who has a serious medical condition and is living in poverty, has a million competing priorities they’re trying to deal with. They need to get to work. They need to pick up their kids from school. Maybe they need to get to their second job. If they also need to see a lawyer, can this be built into the time they’re waiting to see their doctor?

NORMA TINUBU: I think we do have set number of hours, but our attorneys are also very flexible. Most of the appointments come through the social work unit or the doctors themselves and they set appointments. H and H has a great system for setting appointments to see attorneys at our legal clinics during the hours that we’re there.

If we have a patient who’s absolutely unable to come at those set hours, we can be flexible. People can come to our offices downtown. For people who are inpatient, for example, we do go to the bedside and we can make accommodations if a patient is really unable to see us during those set periods because our specialty is helping people who are chronically ill. Who have serious health conditions and so we have to be accommodating of that.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: I imagine that there’s a lot of, especially with public charge, but generally there must just be, people are nervous to go see a lawyer and are nervous to say that they need legal help. Maybe if it’s a dispute with a landlord, for example, you are scared that if you go in with a lawyer that they might try to evict you, or they might try to find some other pretext on which to make your life more difficult. I imagine this connection where you’re able to speak the same language provides some ease and helps to build trust.

NORMA TINUBU: It does. It definitely creates more of a connection with the client. They trust you more if you’re speaking their language and you’re really able to say, “Well, how are you today? And how hard was it to get here? Was it easy to come today? Who referred you?” And you’re able to do all of that in their own language. It does create a special comfort level for the patient. They know that you understand their culture. They know that if they say something that’s really culturally distinct, you understand and there won’t be any misunderstanding.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Do you also think that because the referral is coming from either the doctor, or the social worker, or this care team that they’re already interacting with, does that also help to build trust?

NORMA TINUBU: Absolutely. They already trust and have built up a level of trust with their doctor or their social worker. If that person sends them to us, they know that we’re really there to help and assist. Maybe take care of whatever the problem is that they were sent to the clinic for.

I think that it’s huge that someone made that referral. Someone that they may trust and that they’ve built a relationship with for maybe years. I think that’s what’s important. That’s the most important.

I think if you do speak the language, of course, that you can make an initial connection, but I think the real connection is the client knows that you’re there to help them. Your motive for being there is really to help people. All of us, whether we speak another language or not, can care about people. I think that’s the most important aspect of it.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Obviously, you’re doing your best with every single case, but there must be some cases that you don’t win. There must be some cases, some asylum cases, that are denied, but I think imagining a person who is dealing with a chronic medical condition, even if your asylum application is denied just in the process, having someone batting for you. Having someone helping you that’s a lot of the battle. One, just knowing that there’s someone on your side.

NORMA TINUBU: Exactly. I think when you do have the legal intervention, things don’t happen right away. It’s sort of maybe the bad things don’t happen right away. People have time to prepare. The delay alone gives people room and time to make decisions that are helpful to them in the end.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Well, as we’re wrapping up, it would be great to hear maybe just end on a happy note. A patient you’ve managed to help recently, Norma, who you feel really good about?

NORMA TINUBU: Okay. I can actually continue the story of the patient that was referred by her OB/GYN, who steadily refused to accept care on account of her immigration status. That patient, we since applied for her to become a lawful permanent resident through her spouse. She had her interview last week and she had a very successful interview. We fully expect that she will be granted lawful permanent resident status.

Her enrollment in care was not an issue at her interview. She was very relieved that things went well and that she was able to receive her care. She also had a beautiful baby boy and her son was at the interview as well. She was very happy that she received this really comprehensive legal services through the clinic and through the hospital.

SHANOOR SEERVAI: Well, that’s amazing. Amazing to know that there are so many other patients who you’re able to help in this way. Thank you both so much for joining me today.

NORMA TINUBU: You’re welcome.

EMILY FOOTE: Thank you for having us. It was great.

NORMA TINUBU: Thank you so much.

Show Notes

Illustration by Rose Wong