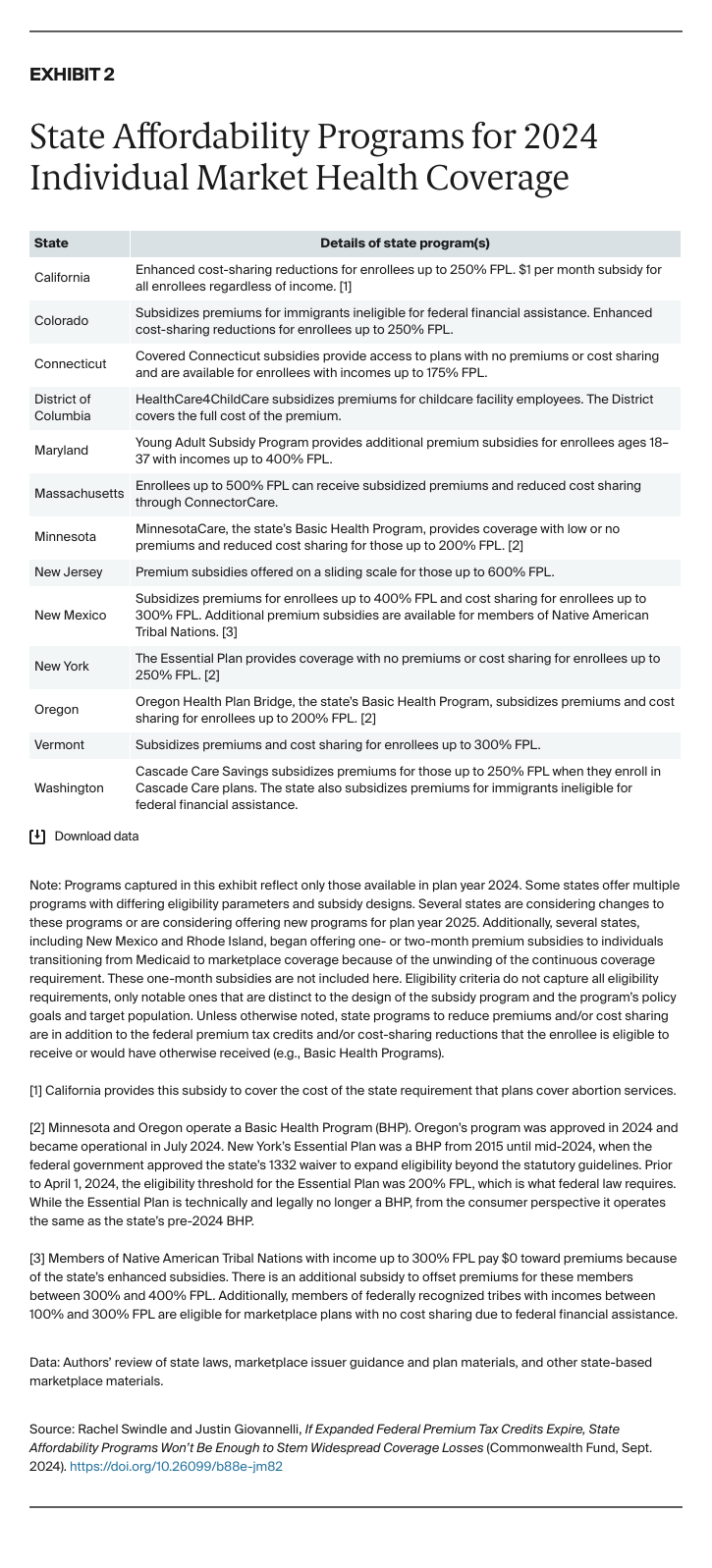

The District of Columbia’s HealthCare4ChildCare program subsidizes marketplace premiums for employees of child care centers, and nearly half the eligible facilities and their employees had enrolled just nine months into the program’s launch in 2023.5 By September 2024, that number increased to 76 percent.6 Since its inception three years ago, Maryland’s Young Adult Subsidy Program, which provides additional marketplace premium assistance for those ages 18 to 37, has significantly increased coverage rates among eligible but uninsured young adults.7 New Mexico’s Native American Premium Assistance program builds on the state’s other marketplace premium subsidy and federal PTCs to ensure that qualifying enrollees with incomes up to 300 percent FPL will have a $0 premium, while those with incomes between 300 percent and 400 percent FPL also receive subsidies on a sliding scale.8 While the total number of enrollees is relatively small compared to overall marketplace enrollment, the state’s targeted subsidies help ensure that enrollees can access low- or no-cost coverage that they might otherwise be unable to afford.9

States also have sought to provide and subsidize marketplace-quality coverage for immigrants ineligible for federal PTCs.10 Colorado’s program has an enrollment cap due to funding constraints; sign-ups reached capacity within two days of the start of open enrollment in each of its first two years.11 When Washington State rolled out its Immigrant Health Coverage program in November 2023, over 2,200 enrolled in 2024 plans.12

States can also structure premium subsidies to target low-income enrollees more generally.13 Thirty-eight percent of Washington’s marketplace enrollees receive state-funded subsidies through Cascade Care Savings — available for those up to 250 percent FPL — and 38,000 pay less than $10 per month through a combination of state and federal subsidies.14 In 2023, 40 percent of marketplace enrollees in New Mexico received additional subsidies through the state’s premium assistance program, and 30 percent paid $0 for coverage as a result of combined federal and state subsidies.15 Because the Covered Connecticut program covers the portion of enrollees’ costs after federal PTCs, eligible residents (those with incomes below 175% FPL) are able to get coverage with no premiums.16 In 2023, more than one in five of Connecticut’s marketplace enrollees received coverage through the program.17

Finally, one state has taken the approach of providing a small premium subsidy to all marketplace enrollees to offset a cost affecting everyone. California, in common with several other states, requires commercial plans to cover abortion services; however, federal law precludes federal dollars, including PTCs, from being used for these benefits. Thus, some enrollees who otherwise would have a $0 premium because of expanded PTCs would instead face a nominal premium connected to these services. In light of a large and ever-growing body of research showing that even minimal costs can discourage uptake and maintenance of coverage, California implemented a $1 per enrollee per month subsidy to offset this cost.18 Under the state program, enrollees maintain access to these essential health services and those who otherwise qualify can receive a plan with a $0 premium.19

Federal Efforts to Improve Affordability Have Enabled States to Relieve Cost-Sharing Burdens

While premium subsidies make it more affordable for consumers to enroll in marketplace coverage, the high and increasing cost of copayments, deductibles, and coinsurance can make it difficult for those with insurance to access care.20 Federal cost-sharing reductions (CSRs) help offset some of these costs for enrollees between 100 percent and 250 percent FPL, and some states have used funds to further reduce consumers’ cost sharing. In 2024, the second year Colorado offered state-funded CSRs on top of the federal CSRs, Colorado increased the eligibility cutoff from 200 percent to 250 percent FPL, and the number of enrollees receiving these state CSRs doubled from 2023 to 2024.21 The state projected that annual deductibles for newly eligible silver-plan enrollees would decrease by 98 percent — from almost $3,500 to $65.22

In 2024, California is for the first time offering enhanced cost-sharing reductions for enrollees up to 250 percent FPL.23 These CSRs increase the value of silver plans to the level of gold or platinum plans, reducing enrollee out-of-pocket expenses and eliminating deductibles — a key barrier to accessing care — in all silver CSR plans.24 In the first open enrollment period with these enhancements, there was a 49 percent increase in silver-plan enrollment among new consumers compared to the prior year’s enrollment trends, and over 800,000 people benefited from the state-enhanced CSRs.25

New Mexico’s cost-sharing assistance program, which is available for those with incomes up to 300 percent FPL, ensures that enrollees’ out-of-pocket costs will be significantly lower than the federal limitations and expands access to higher-value plans for enrollees with incomes between 250 percent and 300 percent FPL who would otherwise be ineligible for federal CSRs.26 In 2023, these enrollees constituted 44 percent of marketplace enrollment, which increased to nearly 54 percent of total enrollment by July 2024 — illustrating the need for, and responsiveness to, reduced out-of-pocket expenses.27

The Most Comprehensive Affordability Programs Receive Significant Federal Funding

Four states provide individual market consumers access to comprehensive coverage on notably more generous terms than the subsidy programs described above. Massachusetts offers substantial marketplace premium and cost-sharing assistance to individuals with incomes up to 500 percent FPL via the ConnectorCare program, a cornerstone of its pre-ACA health reform efforts.28 Minnesota, New York, and Oregon have used ACA flexibilities to provide low-income individuals affordable coverage that bridges Medicaid and the marketplace. Minnesota and Oregon operate ACA-authorized Basic Health Programs (BHPs), which provide heavily subsidized insurance to individuals with household incomes up to 200 percent FPL who otherwise would be eligible for marketplace subsidies.29 Until recently, New York also administered a BHP, called the Essential Plan. In 2024, the state used an ACA waiver to implement a successor program with a similar structure — and the same name — but expanded eligibility to reach individuals up to 250 percent FPL.30

While Oregon’s program is new — its BHP launched in July 2024 — the other programs now have long track records of enrolling residents in affordable comprehensive coverage. Prior to its recent expansion, Essential Plan enrollment exceeded 1.1 million, for a take-up rate of 97 percent (compared to about 200,000 and 72% for New York’s marketplace).31 For individuals with incomes from 100 percent to 199 percent FPL — roughly the target population of the BHP — the uninsured rates in Minnesota (8.3%) and New York (8.0%) in 2023 rank among the lowest nationwide.32 Meanwhile, ConnectorCare has helped Massachusetts achieve the lowest overall uninsured rate in the nation (2.8% in 2023).33

All four states made important policy commitments and expended significant resources to establish and administer these programs. At the same time, the relative generosity of the financial assistance that they provide, and that makes them successful, is attributable in substantial part to federal dollars. ConnectorCare’s subsidies are supported by federal funds that flow to the state pursuant to a longstanding Medicaid Section 1115 waiver. States’ BHPs receive federal funding equal to 95 percent of what the federal government otherwise would have spent to subsidize enrollees’ marketplace coverage. In practice, these federal payments cover most BHP costs.34 In New York, federal BHP payments were sufficient to fund the Essential Plan in its entirety; the program is now fully financed by monies available under its new federal waiver.35

There is surely value in determining whether these programs’ achievements can be replicated. The answer is not straightforward, however, and depends on state-specific factors.36 For example, New York’s especially high enrollment and low state expenditures may reflect unique regulatory and market conditions not present elsewhere.37 Notably, because federal support for BHPs is a function of federal spending on PTCs, expanded federal premium assistance has provided a significant financial lift to these programs.38

If Expanded Federal PTCs Expire, States Will Not Be Able to Avoid Coverage Losses

The temporary federal PTC expansion has been a boon to state and federal efforts to reduce the uninsured rate and boost marketplace enrollment. But these gains will disappear if it is allowed to expire after 2025.39 The Congressional Budget Office has published increasingly dire estimates of these impacts. Its most recent projection shows marketplace enrollment decreasing precipitously — 7 million people dropping coverage — in the first two years after the temporary PTCs expire.40 Moreover, the loss of enhanced PTCs is expected to cause disproportionate numbers of younger, healthier enrollees to drop coverage. This will leave the remaining risk pool sicker and therefore more costly, contributing to even greater premium increases.41 While the uninsured rate is currently at a record low, it’s projected to increase in the coming years, due in large part to the loss of enhanced PTCs.42

These impacts would vary by state, but even states with generous affordability programs will not be able to shield marketplace enrollees from the sharp reduction in federal PTCs.43 For example, state officials estimate that more than 55,000 current enrollees in Washington State, between 187,000 and 246,000 in California, and over 40,000 in Colorado will drop coverage should the enhanced PTCs expire — this despite the fact that all three states invest substantial funds in subsidies for individual market enrollees.44

Discussion

Thirteen states administer programs that reduce premiums or cost sharing for individual market consumers, and these initiatives have produced real benefits that can inform state policymakers elsewhere.45 While several are long-running, most programs are fairly new, having launched or been substantially modified after the 2021 expansion of the federal PTC.

These recent state efforts were designed as a complement to expanded federal premium assistance, while the influx of federal support has made some older programs, such as Minnesota’s and New York’s, more financially secure. None of these initiatives is a substitute for expanded premium tax credits, nor is there reason to expect that any state could overhaul their program to replicate it. If Congress lets this valuable federal assistance expire, no state is likely to be able to deploy the resources needed to weather the loss.46