Abstract

- Issue: Childhood vaccination rates fell worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, reductions in childhood vaccination were not universal, which may be related to differences in vaccine eligibility, vaccine hesitancy, and vaccine administration programs across countries.

- Goals: Explore how childhood vaccination rates changed during the COVID-19 pandemic in five high-income countries with varying approaches to vaccine policy.

- Methods: Surveys of in-country experts and analysis of secondary data sources in Australia, Germany, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

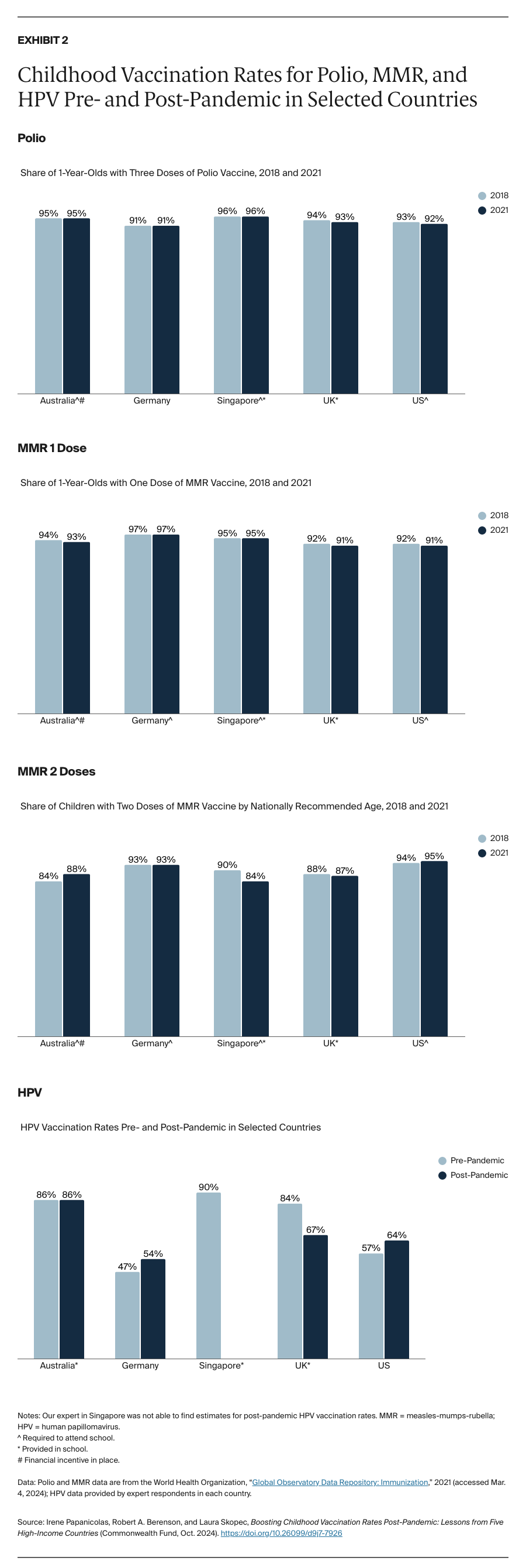

- Key Findings and Conclusion: While vaccination rates fell worldwide during the COVID-19 pandemic, the high-income countries in our study maintained high childhood vaccination rates for polio and measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) near or above the herd immunity threshold (80% for polio and 95% for measles). Australia and Singapore, which have the strictest vaccine requirements, boasted the highest polio vaccination rates in both 2018 and 2021. No countries require the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination nationwide, but Australia, Singapore, and the U.K. have school-based HPV vaccination programs and high vaccination rates. Strong vaccine requirements, combined with school-based immunization or catch-up programs, may help boost childhood vaccination rates where they lagged during the pandemic.

Introduction

In 2022, public health authorities detected polio in wastewater in London and in New York, where a polio infection was also reported.1 Reductions in childhood vaccination rates during the COVID-19 pandemic and increasing vaccine hesitancy in the United States may have contributed to polio’s reemergence, as well as to measles outbreaks in the U.S. in 2024.2

Across high-income countries, vaccine policies, including where routine vaccines are administered, vary significantly. The likelihood of parents or guardians delaying or refusing vaccines for their children also varies.3 These differences partly are a result of variation in the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic across countries and the extent of disruptions in preventive care, including childhood vaccinations.4 These factors may have contributed to the variability in vaccination rates during the pandemic across countries.

With support from the Commonwealth Fund and its network of international health care leaders,5 we explored differences in eligibility, administration, requirements, and pandemic-related disruptions for three routine childhood vaccinations: polio, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), and human papillomavirus (HPV). We selected these vaccines because they are administered at different ages, face differing requirements and penalties, and were approved for use at different times.6 Our research focused on five high-income countries that have varying childhood vaccination policies: Australia, Germany, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The selected countries are among those regularly studied by the Commonwealth Fund’s International Health Policy and Practice Innovations program.7

Key Findings

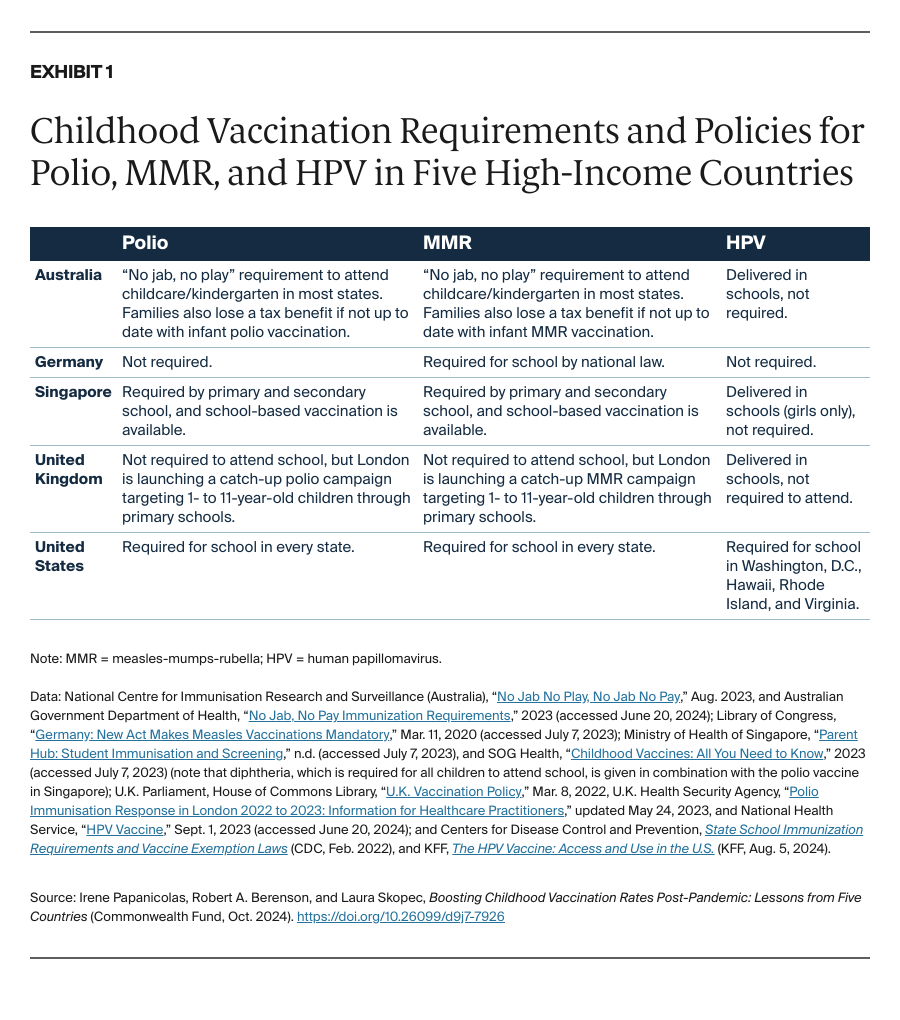

Childhood vaccination policies vary across the five countries and by vaccine type (Exhibit 1). Australia, Singapore, and the U.S. require polio and MMR to attend school, while Germany only requires MMR. Accordingly, Germany has higher immunization rates for MMR than polio, for which vaccination is not mandated (Exhibit 2).