Abstract

- Issue: Nine years since the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid coverage expansions took effect, 10 states have yet to expand eligibility for their Medicaid programs. Some residents with low income are falling through the resulting “coverage gap” — their incomes are too high to qualify for their state’s Medicaid program but too low to qualify for marketplace plan subsidies, thereby impeding their access to health care.

- Goals: Assess how being in the Medicaid coverage gap affects insurance coverage and health care utilization.

- Methods: Analysis of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2011–2013 and 2017–2019, to compare outcomes for people who potentially fall in the coverage gap (those with incomes between pre- and post-ACA eligibility levels) in comparable states that did and did not expand Medicaid.

- Key Findings and Conclusion: In expansion states, people who would otherwise be in the Medicaid coverage gap had increased health insurance coverage, lower rates of avoiding seeking medical care, and greater utilization of certain preventive care measures.

Introduction

A key provision of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was the requirement that states expand Medicaid eligibility to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level. After the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that the penalty associated with this requirement was unconstitutionally severe, states could choose whether to adopt the reform.1 Twenty-six states including the District of Columbia expanded Medicaid initially, and 15 others followed suit. As of September 2023, 10 states have not expanded eligibility.2

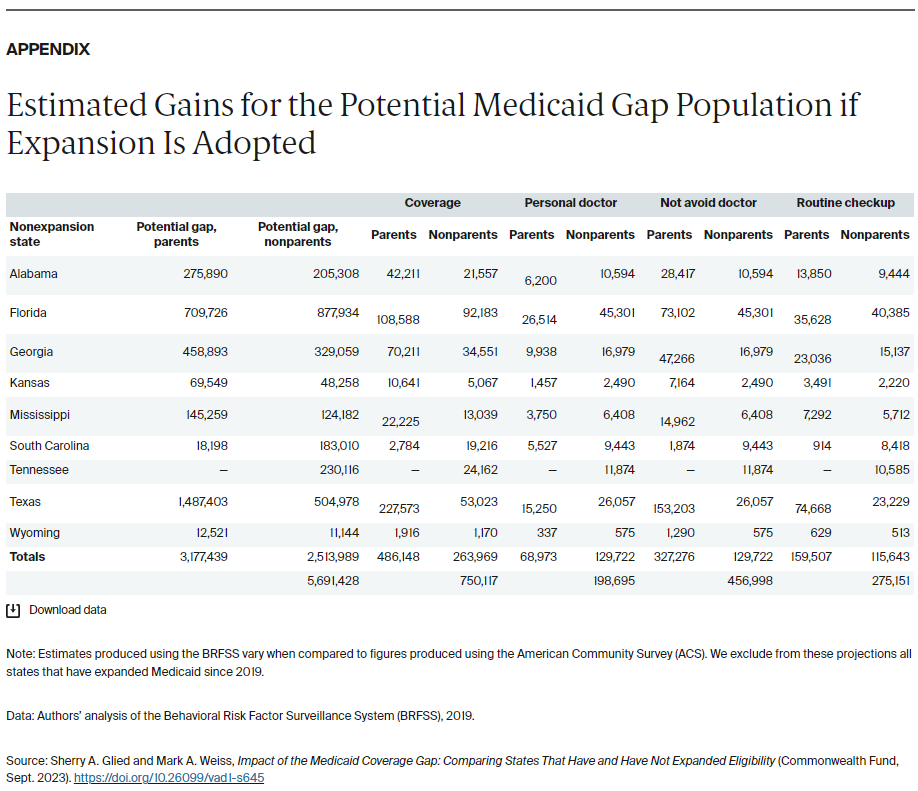

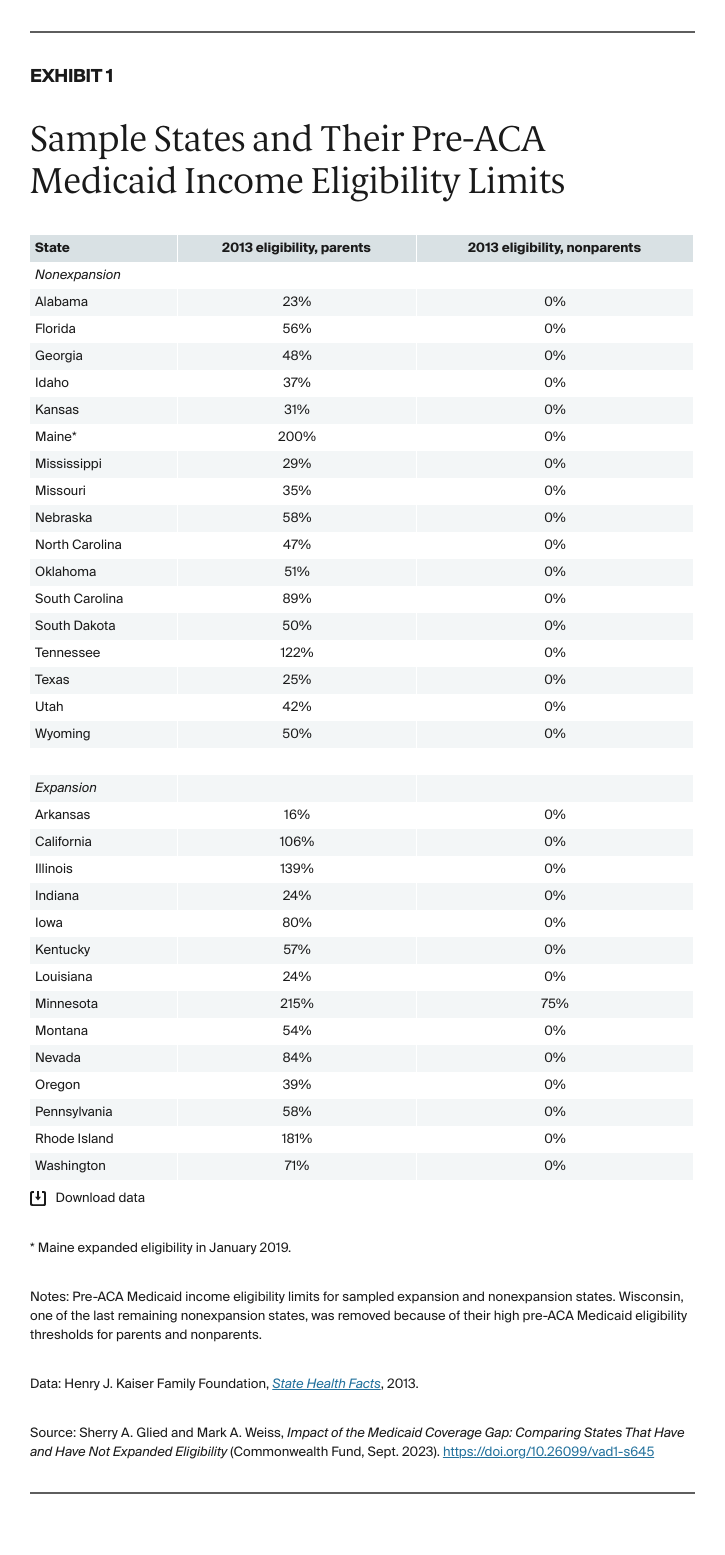

The effects of expansion varied because, prior to the ACA, states could set their own Medicaid income eligibility thresholds for nondisabled adults who were not pregnant. They also could vary these thresholds by population, typically setting different eligibility thresholds for parents and nonparents (Exhibit 1).3 As well as establishing a standard national income eligibility threshold of 138 percent of poverty for Medicaid, the ACA introduced marketplaces offering subsidized coverage to people with incomes above 100 percent of poverty. This structure means that those in nonexpansion states with incomes above their state’s Medicaid eligibility threshold but below 100 percent of poverty are not eligible for any subsidized coverage. According to prepandemic estimates, about 2.2 million Americans fall into this Medicaid coverage gap, the majority of whom are people of color and people living in the South.4

Research has overwhelmingly established that Medicaid expansion increased health care coverage, access, and utilization among low-income Americans.5 Evidence on health outcomes is sparser, reflecting the complex relationship between health insurance coverage and health outcomes.6 However, a recent study found that the ACA Medicaid expansions reduced disease-related mortality among older adults.7

Few studies have assessed the impacts of nonexpansion on the millions of low-income Americans who fall into the Medicaid coverage gap, and what evidence exists is often dated and state-specific. A study in North Carolina found that people in the Medicaid coverage gap are less likely to have a regular source of care, less likely to have had a routine checkup in the past year, more likely to forgo a doctor’s visit and skip medication because of cost concerns, and more likely to have multiple chronic conditions or live with a disability.8 Zhang and Wu found similar results in Texas, and Han et al. found that chronic condition patients were less likely to adhere to prescription medication if they fell into the Medicaid coverage gap.9

In this study, we look across states to see how the Medicaid coverage gap population was faring immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic. We use the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) to compare outcomes for the potential Medicaid coverage gap population — those with incomes between their states’ pre-ACA eligibility level for their population group and 100 percent of poverty — in nonexpansion states and comparable expansion states (for details, see “How We Conducted This Study”). We studied the experience of parents and nonparents separately, as these two groups differ in average age and health. Our analyses controlled for sex, race, age, education, employment status, and whether the respondent owns their home; included state and year fixed effects; and clustered standard errors at the state level.

Key Findings

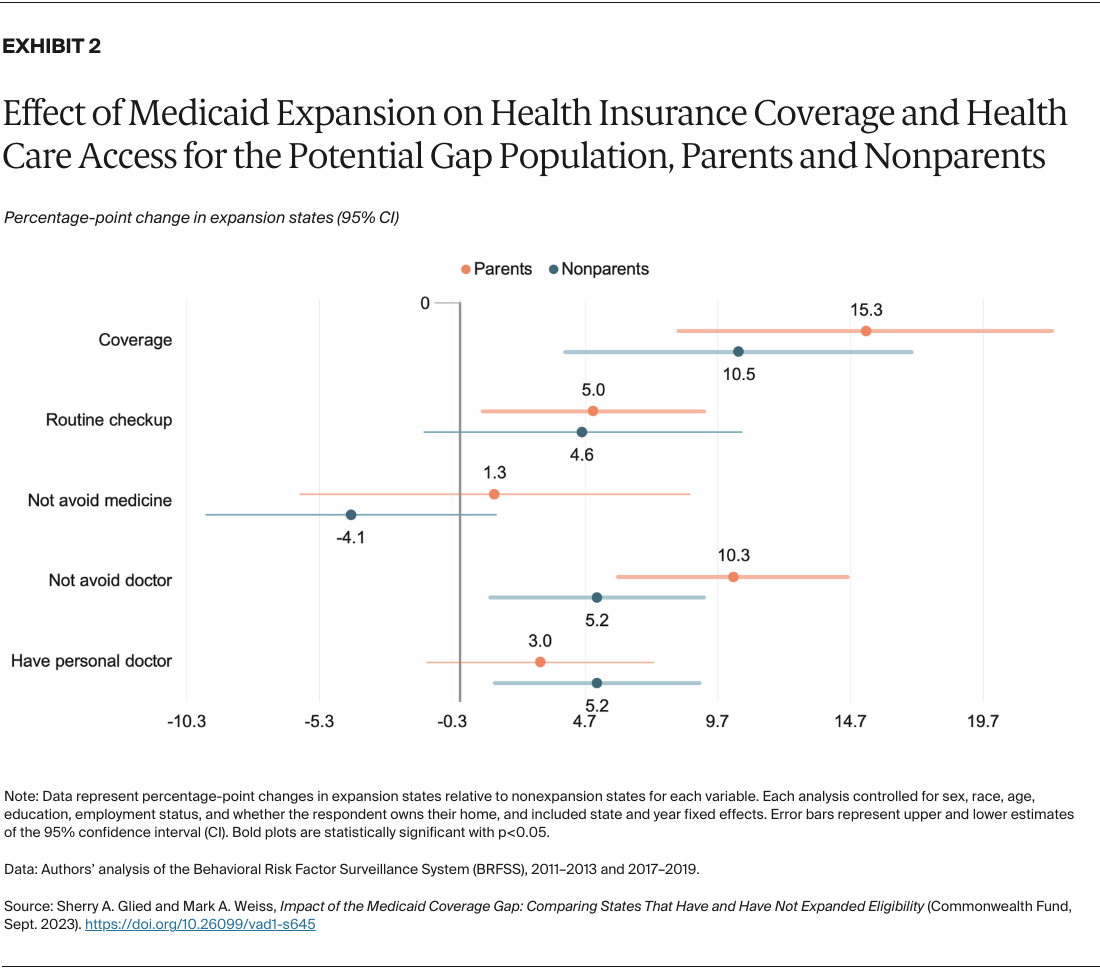

Medicaid expansion increased health insurance coverage and access for the potential gap population.

The most direct effect of Medicaid expansion was to substantially increase health insurance coverage rates for the potential gap population. In expansion states, insurance coverage rates among parents increased by 15.3 percentage points and rates among nonparents increased by 10.5 points (Exhibit 2). These improvements in coverage led to reductions in the rate at which financial considerations impeded access to care.