Introduction

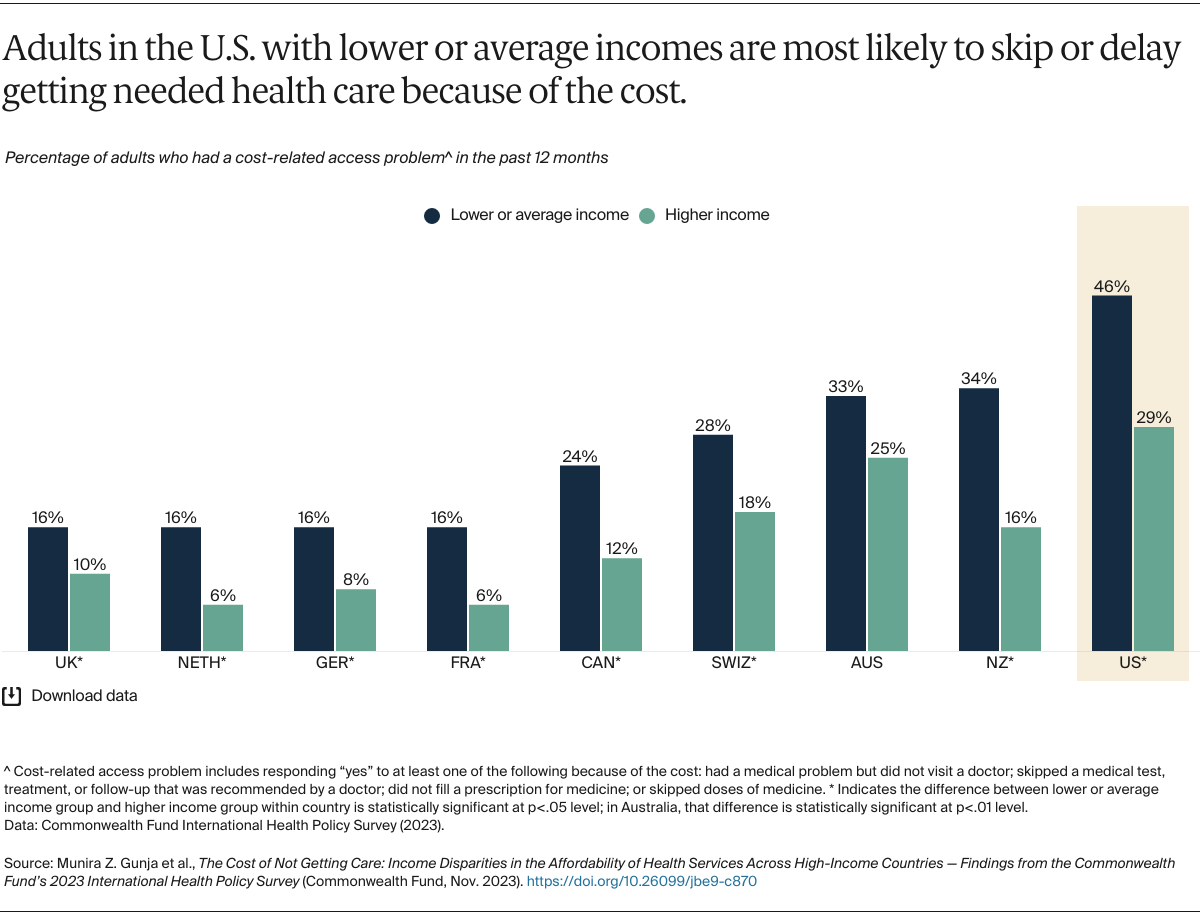

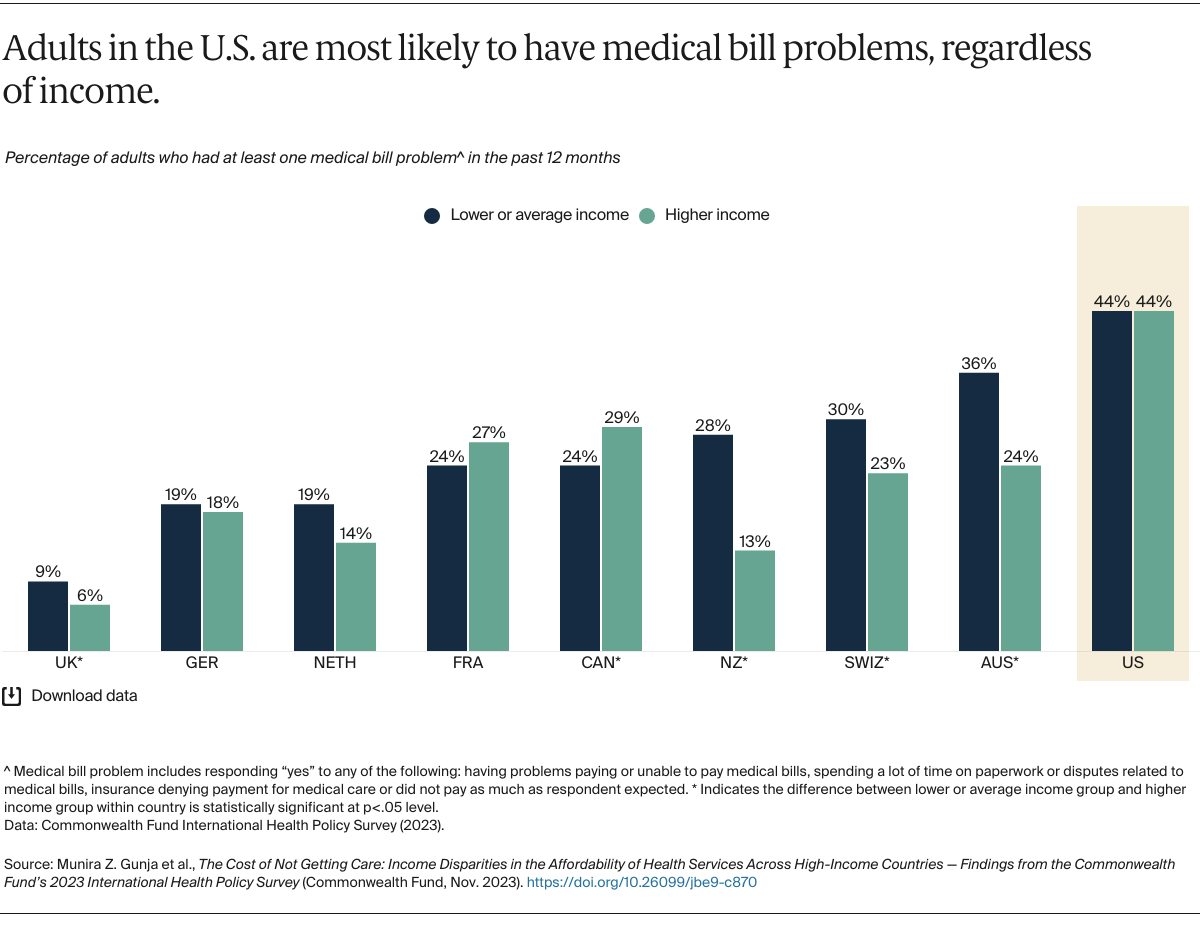

Over the past four decades, government and individual health spending as a share of the overall economy has been steadily rising around the world, partly because of advances in medical technologies and greater demand for health services.1 In the United States, where administrative costs and health care prices are higher than in other high-income countries, this increased spending has meant higher insurance premiums and deductibles.2 Nearly a quarter of the U.S. population is covered by a health plan all year that doesn’t ensure affordable access to care.3

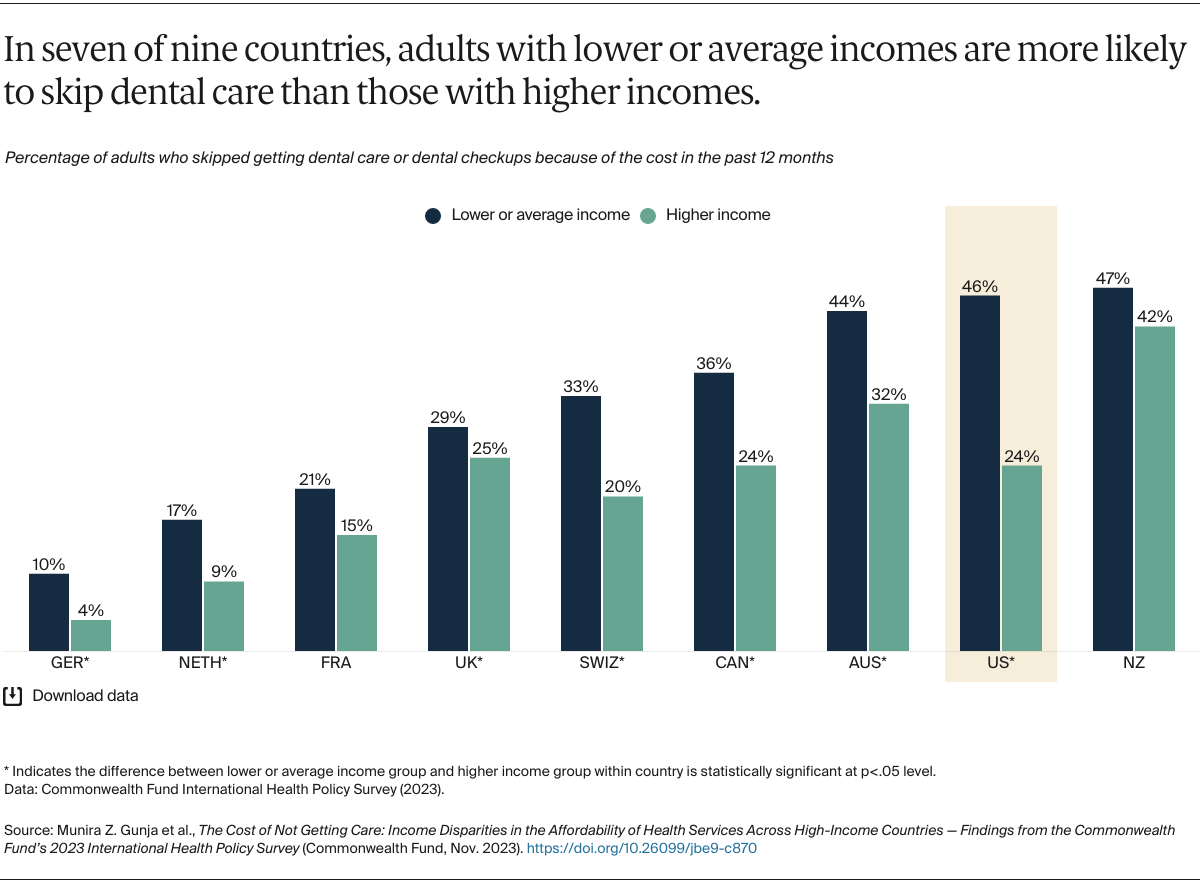

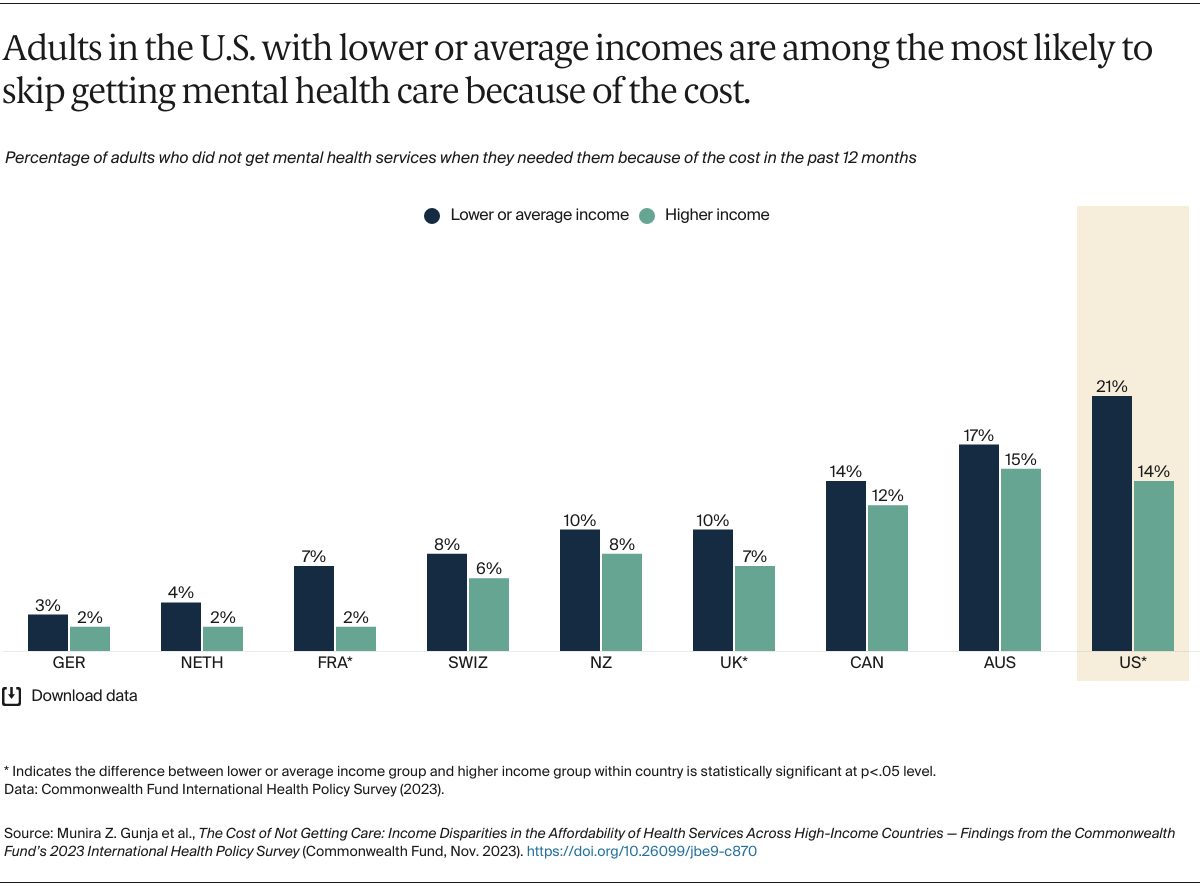

The U.S. is the only high-income country without universal health coverage; about 8 percent of the population is uninsured.4 But universal coverage — while critical to ensuring that health care is accessible and affordable — is not always enough. Even some countries that provide coverage to all their citizens grapple with rising health care costs, which can trickle down to patients in the form of higher out-of-pocket costs and, for those with private plans, higher premiums. These costs most severely impact households with low incomes, people of color, and rural residents.5

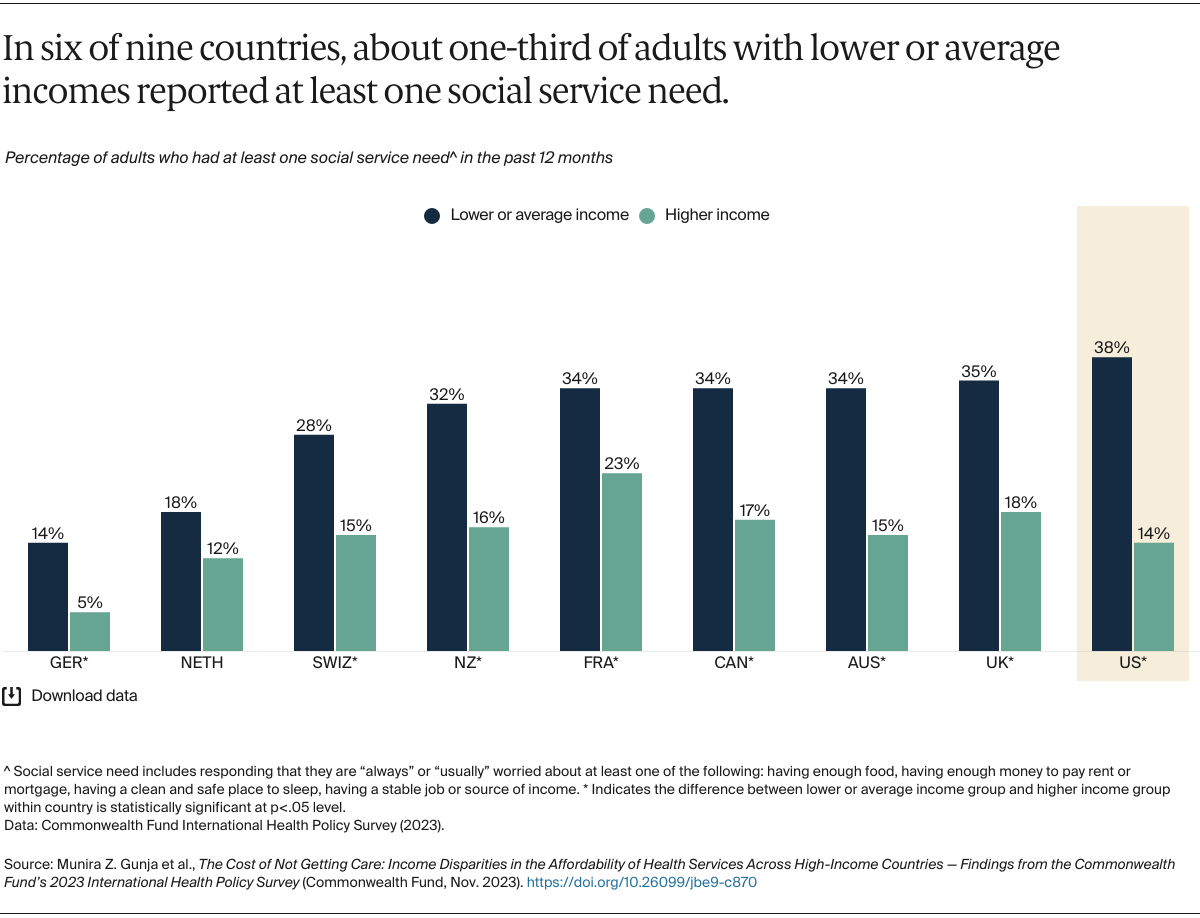

This brief presents the first findings from the Commonwealth Fund 2023 International Health Policy Survey, which engaged adults age 18 and older in 10 countries to explore how financial barriers affect their health care decisions. The survey findings were analyzed by self-reported income level relative to the average annual household income to identify differences in each country between those with lower or average incomes and those with higher incomes. (See “How We Conducted This Survey” and “How We Conducted This Analysis” for more details. Because of data protection and privacy laws, data could not be provided on average annual household income in Sweden. Respondents from Sweden, therefore, were not included in this analysis.)