Abstract

- Issue: In response to the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, a number of states have passed, or are planning to pass, partial or complete bans on abortion. A key question is whether these restrictions will result in reduced overall access to maternal and infant care, as well as worse health outcomes, in these states.

- Goals: Compare the current status of maternal and infant health in states that have or are likely to have bans or restrictions on abortion access with states that will preserve abortion access and consider how new abortion restrictions could affect maternal and infant health in the future.

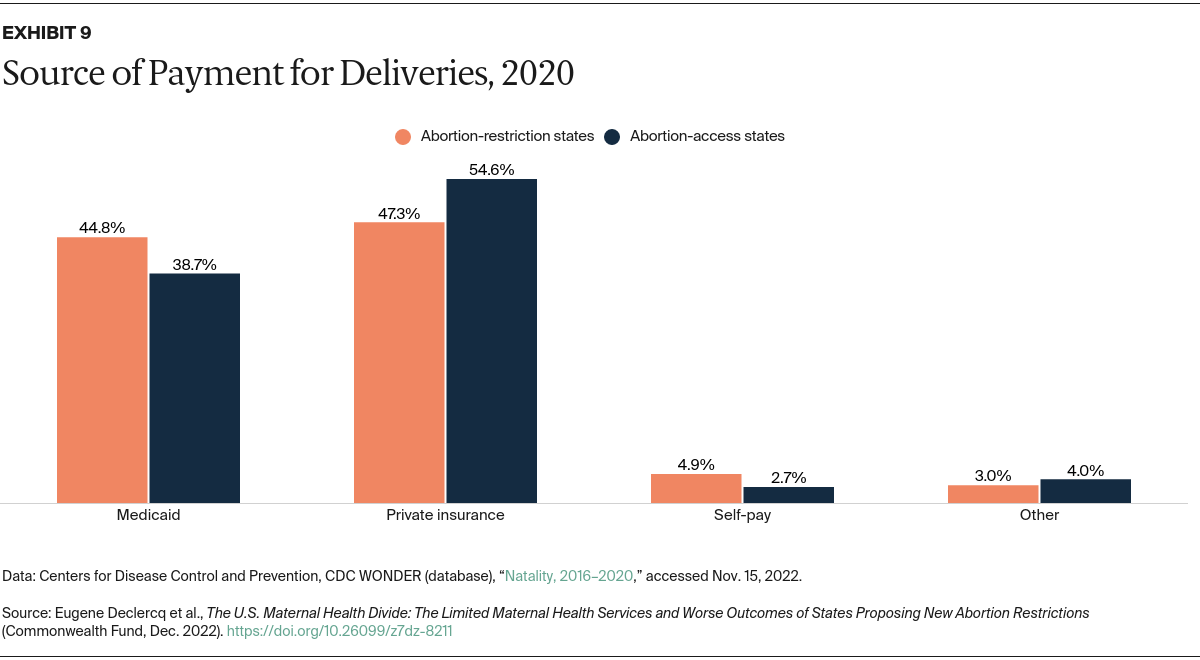

- Methods: We drew on public data sources such as the CDC WONDER birth and death files, Area Health Resources Files, and the March of Dimes maternity care deserts report. We stratified states based on Guttmacher Institute ratings of the restrictiveness of state abortion policies.

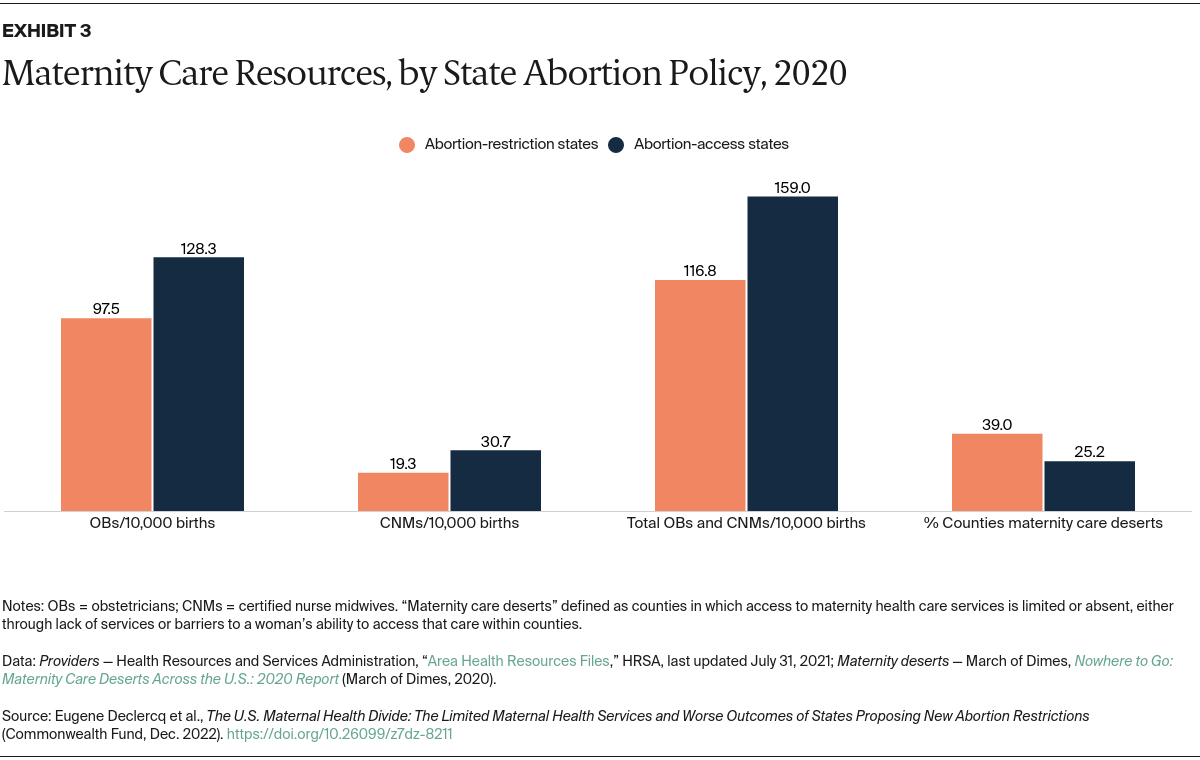

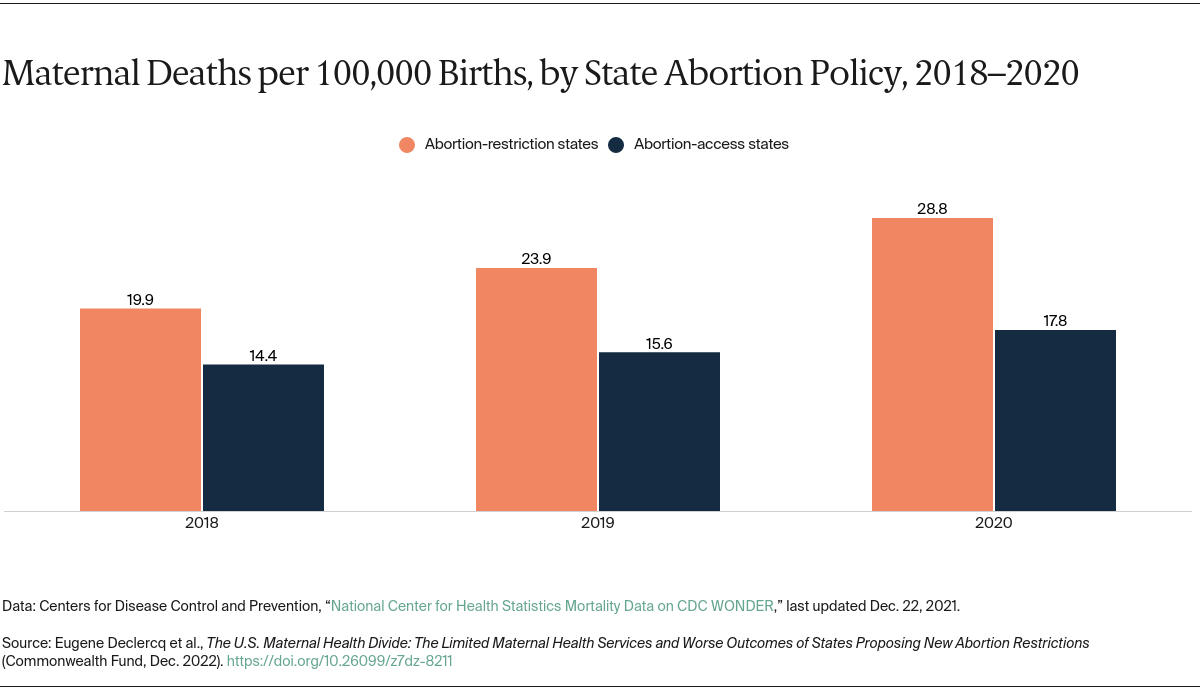

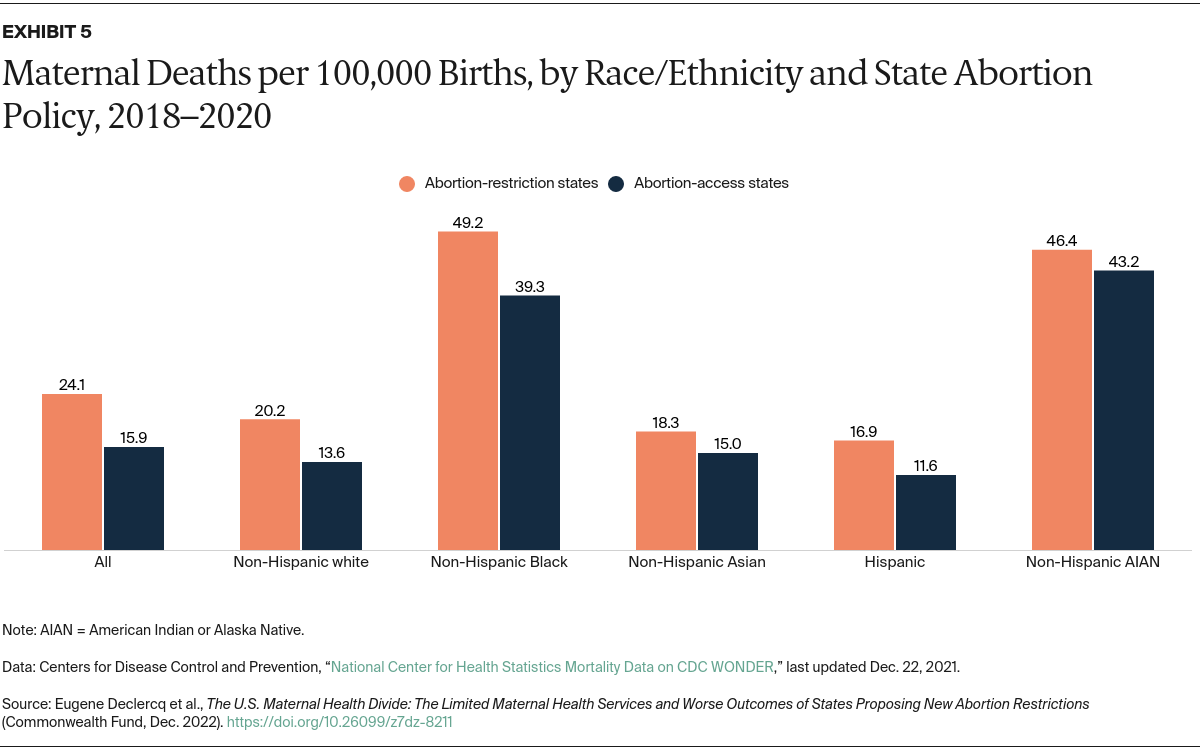

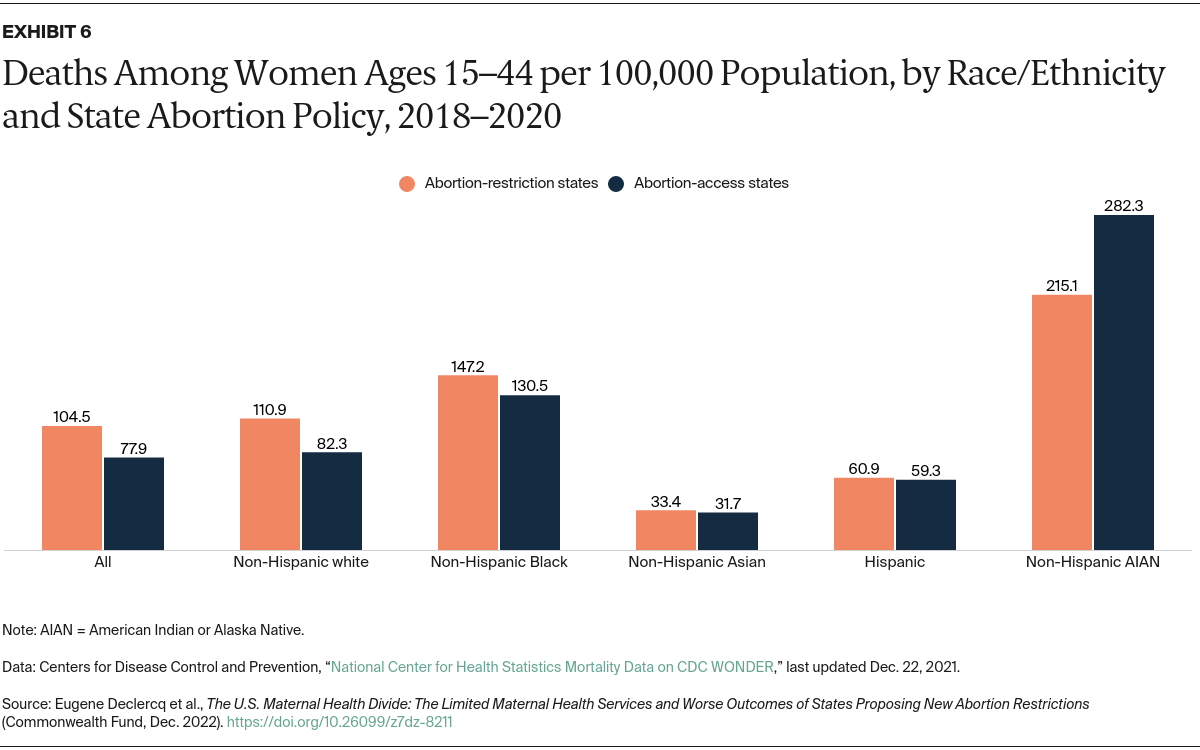

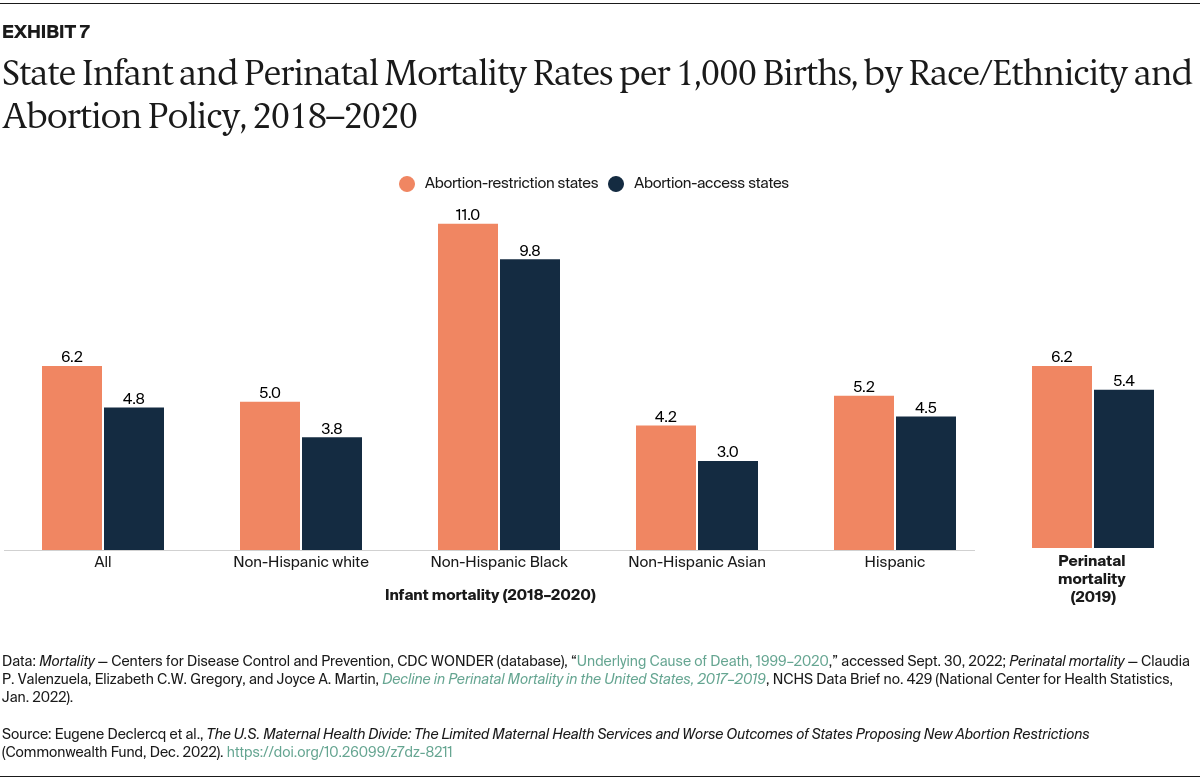

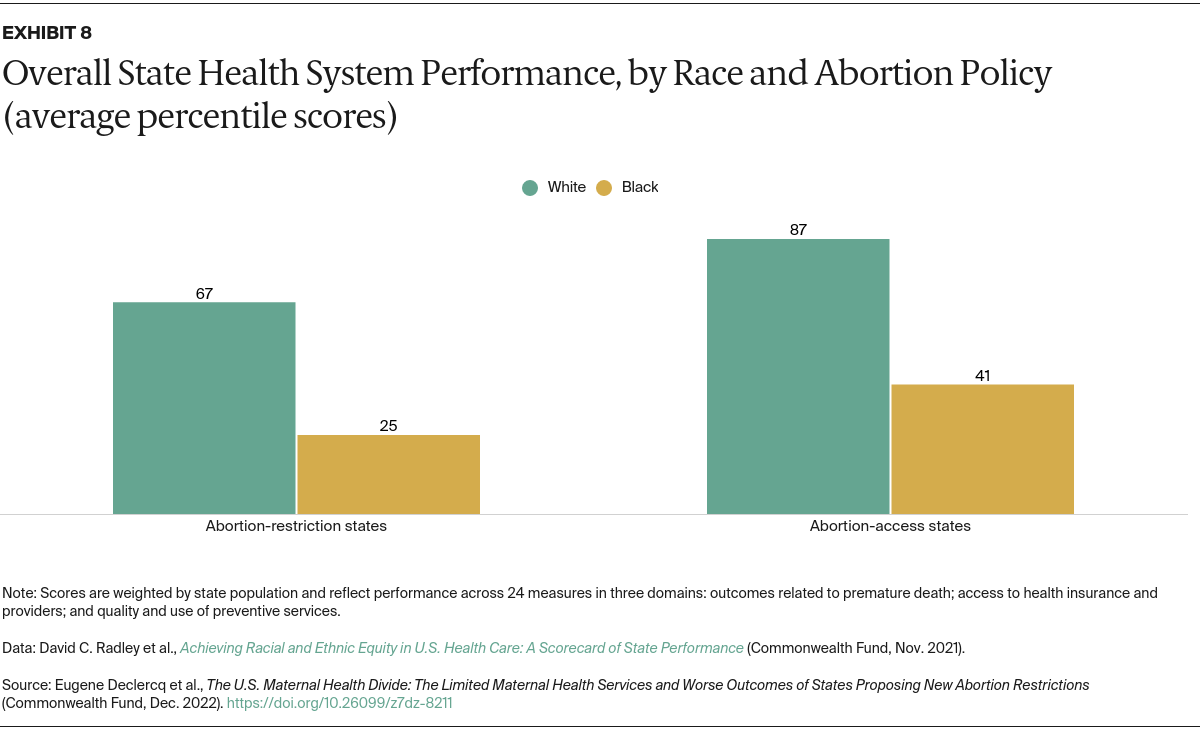

- Key Findings and Conclusions: Compared to states where abortion is accessible, states that have banned, are planning to ban, or have otherwise restricted abortion have fewer maternity care providers; more maternity care “deserts”; higher rates of maternal mortality and infant death, especially among women of color; higher overall death rates for women of reproductive age; and greater racial inequities across their health care systems.

Introduction

In anticipation of a U.S. Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, a number of states passed “trigger laws” that would ban all, or nearly all, abortions once national abortion protections ended. In the months since the Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in June 2022, several of these states have in fact banned abortion in most instances.1 Other states have enacted bans or severe restrictions since then, and others may do so in the coming months or years.2

In this brief, we assess the current state of maternal and infant health in these states, identify weaknesses in perinatal care systems, and consider how abortion bans may exacerbate these weaknesses. We compare states that have current or proposed abortion bans or restrictions with states that are unlikely to pass such restrictions, focusing on the following areas:

- the availability of maternal care resources such as maternity care providers

- maternal and infant health status and outcomes

- health coverage policies related to accessing maternity care

- performance of the health system in providing equitable access and care.

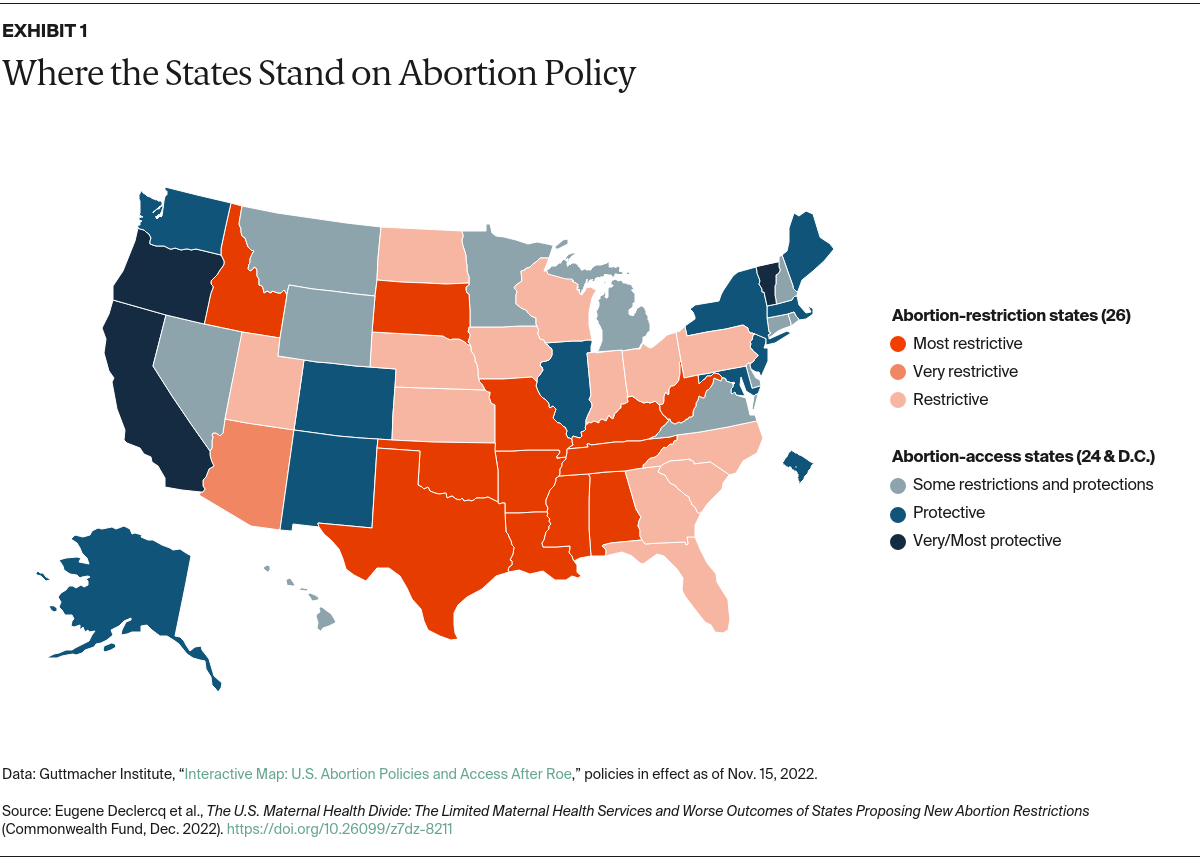

For our analysis, we compared health status and health care resources in the 26 states that the Guttmacher Institute has identified as having “restrictive,” “very restrictive,” or “most restrictive” policies on abortion — which we refer to as “abortion-restriction states” — to those in the 24 “abortion-access states” that, along with the District of Columbia, have not instituted bans or new restrictions on abortion.3

Findings

Demographic Comparison of States With and Without Abortion Restrictions

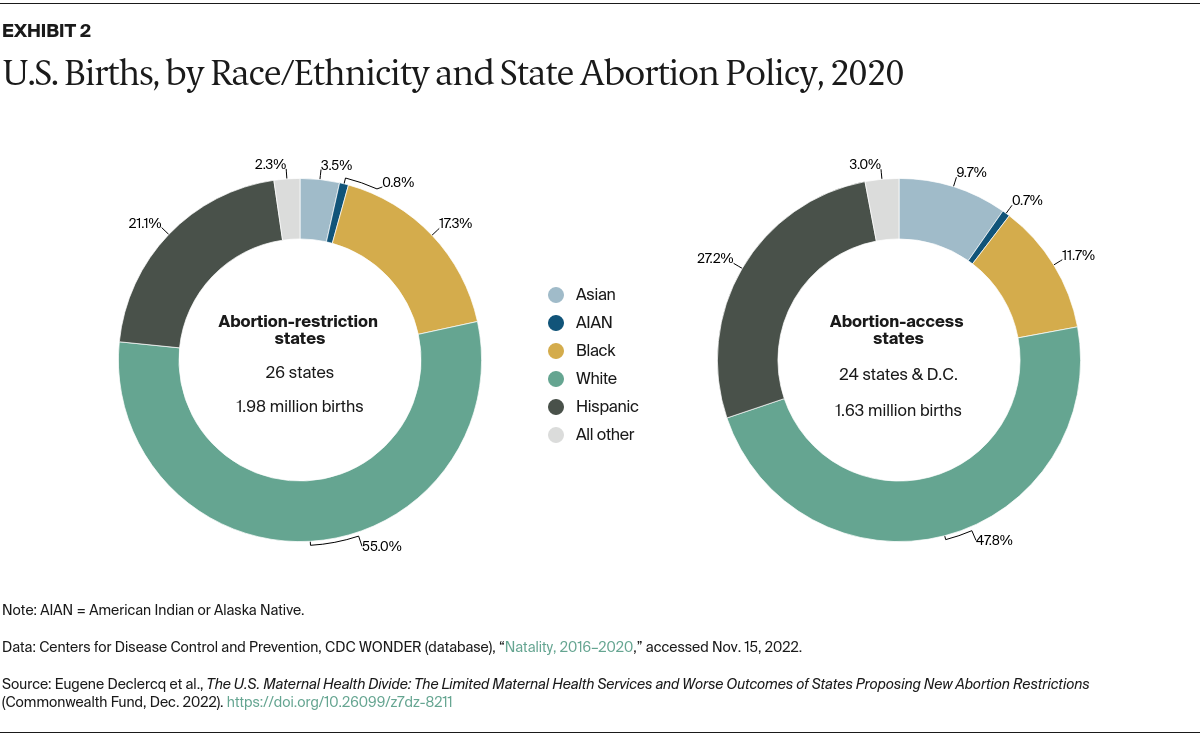

The 26 states with abortion bans or restrictions (Exhibit 1) had slightly more than half (55%) of U.S. births in 2020. These states differed demographically from states with abortion access, as shown in Exhibit 2, with larger proportions of births to non-Hispanic white mothers. Abortion-access states, meanwhile, had a majority of births to women of color.