One effect of the reform is that more than 90 percent of information needed for budgeting is now consolidated into one financial management system. The nation has not yet been able to fund investment in interoperable electronic health records, however.

Before reform, public hospitals were given budgets by their respective district health boards, based primarily on historical usage and projections of population health needs. Nationwide, Te Whatu Ora is moving to rolling multiyear forecasting and budgeting, so budgets will be updated on an ongoing basis. Allocations for individual hospitals — effectively, their global budgets — will be determined based on inpatient, outpatient, and operating room activity levels, both past and projected, along with labor costs and inflation. Hospitals’ budgets include costs of specialty care physicians, who are salaried, though many specialists also have separate private practices.

Norway

Norway has a system of universal, compulsory health care coverage funded and administered by the national government in concert with municipalities. Public financing of health care, at more than 85 percent of total spending, is the highest of all 51 nations in the World Health Organization’s European region, and total health expenditures as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) are the fifth highest.18 Private insurance does exist, mainly offering speedier access to private specialists, but it accounts for less than 3 percent of all health spending.

Municipalities organize and run primary care and other basic services. The national government funds specialized care including hospital services. Its Ministry of Health and Care Services governs four regional health authorities that own and control 20 hospital trusts. The hospitals either employ specialty care physicians or contract for their services on a lump-sum basis.

Hospital funding starts with the parliament budgeting annually for health care spending. The ministry apportions that budget among the regional health authorities based on population characteristics and health needs. Each regional health authority splits its hospital spending budget among its hospitals and has latitude to pay hospitals mostly as it chooses, though they all use the same methodology.

Before 1980, hospitals in Norway were compensated on a per diem basis, with fixed daily rates for services provided. Block grants (fixed global budgets) were used from 1980 to 1997. Since then, a combination of fixed and variable payments has been in operation.

The fixed component is a block grant that amounts to 60 percent of the target global budget. The remaining 40 percent of funding is activity-dependent, using DRG-style case payments. The expectation is that the hospital will deliver a quantity and mix of services that will bring its revenues to within 1 percent to 2 percent of its global budget. The regional health authorities customarily set high activity targets relative to hospitals’ actual capacity, however, so few hospitals ever realize their full potential global budget revenues.

Quality-based payments were introduced in 2014 and amount to just 0.5 percent of hospital funding. Quality measures focus on patient experience of care.

In theory, at least, a hospital that strives to build up volume may receive little extra money if actual activity exceeds the target. However, under limited circumstances, such as if a hospital sees an extraordinary caseload and other hospitals in the region do not reach their budgeted variable pay levels, the regional health authority may grant it more funding.

Generally, Norway’s hospital trusts fund capital investment out of their regular allocations from the regional health authorities. For large capital projects, a trust may apply to the ministry for 70 percent of the funding.

Comparison of Global Budgeting Approaches

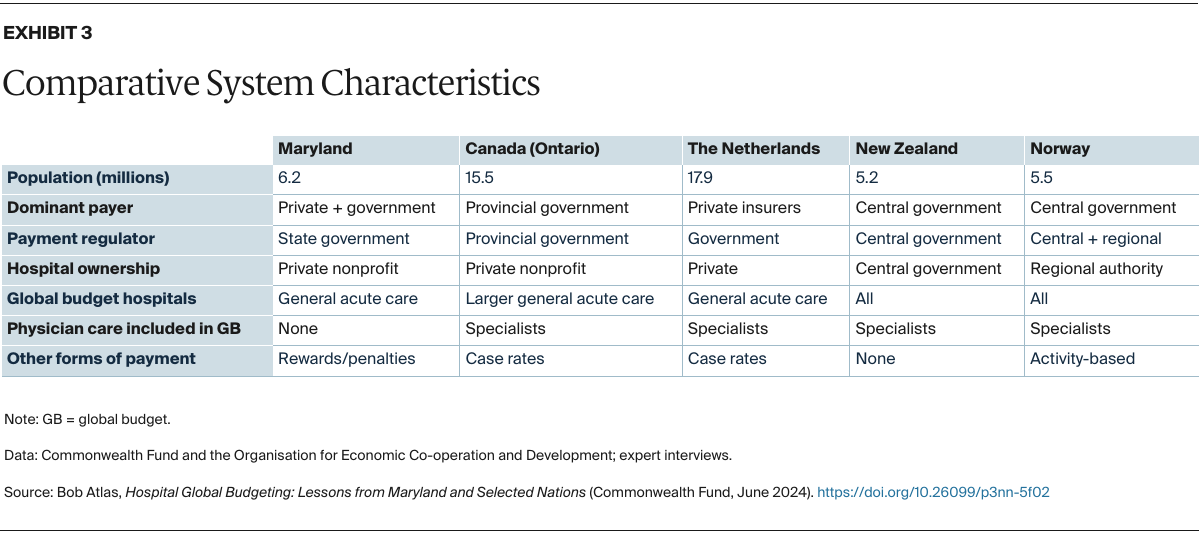

To borrow from an old adage: When you’ve seen one nation’s hospital global budgeting scheme, you’ve seen one nation’s hospital global budgeting scheme. Comparing the five global budgeting models described above demands understanding the characteristics of their broader health care financing and delivery systems.

Where Government Runs Everything

The national governments of New Zealand and Norway both own the facilities that deliver almost all hospital care and fund health coverage using social insurance. So, for those countries, hospital global budgeting could be equated to departmental budgeting within a single corporation. No negotiation is needed between independent parties.

Total funding for hospitals and methods of allocation to individual hospitals reflect national sentiment about what is most important in both nations. New Zealand’s government aims to redirect resources to prevention and primary care, hoping to lessen the need for acute and curative hospital care. Norway also prizes prevention, plus social supports that boost well-being, such as childcare and housing. Another priority is to ensure access to the full range of care for the 20 percent of Norwegians who live well outside the urban areas. Efficiency is certainly desired, but is not given the most weight, as reflected by Norway’s comparatively high investment in health care.

Where Hospitals Are Privately Owned

In Canada, the Netherlands, and Maryland, almost all hospitals are private nonprofit institutions that operate at arm’s length from the government. Yet they depend on government for much of their funding and are regulated by government in many respects. A common thread in all three cases is that hospitals assertively advocate for their interests.

There are clear differences, though. Canada’s federal and provincial governments provide social insurance to pay for health care. In the Netherlands, private nonprofit health insurers — heavily regulated by the national government, which also contributes more than half of all premiums — bear the insurance risk and pay for care. In Maryland, health insurance is furnished by multiple public and private insurers, and the state has a statute and special federal government dispensation to regulate how all those payers pay hospitals.

In Ontario, the Netherlands, and Maryland, hospital global budgeting takes different forms, and all three of their programs are continually evolving.

Experience Drives Changes to Payment Policies

Since 2012, Ontario has pointedly moved away from the classic model of global budgeting, believing that it stifled provider initiative and innovation. Ontario’s health system funding reform was meant to “strengthen the link between the delivery of high-quality care and fiscal sustainability.”19 So now, hospital payment in the province is only about one-third fixed. The rest is variable, partly to reward the more efficient hospitals and partly to acknowledge intrayear differences in hospital volumes.

Hospital representatives in Ontario nevertheless point to the funding model as a cause of capacity limits and associated waiting lists for many procedures. Rapid population growth in recent years stemming from international immigration further strains hospitals’ finances.

In the Netherlands, all-encompassing fixed global budgets were discarded in 2006 along with the dismantling of the single-payer system. Now, competing insurers negotiate independently with hospitals to set global budgets based on their own price schedules and utilization forecasts, somewhat like capitation — which involves a fixed prepayment per person per unit of time — but without the prepayment feature. Additionally, there are signs that global budgets in the Netherlands are becoming more like targets than definitive commitments.

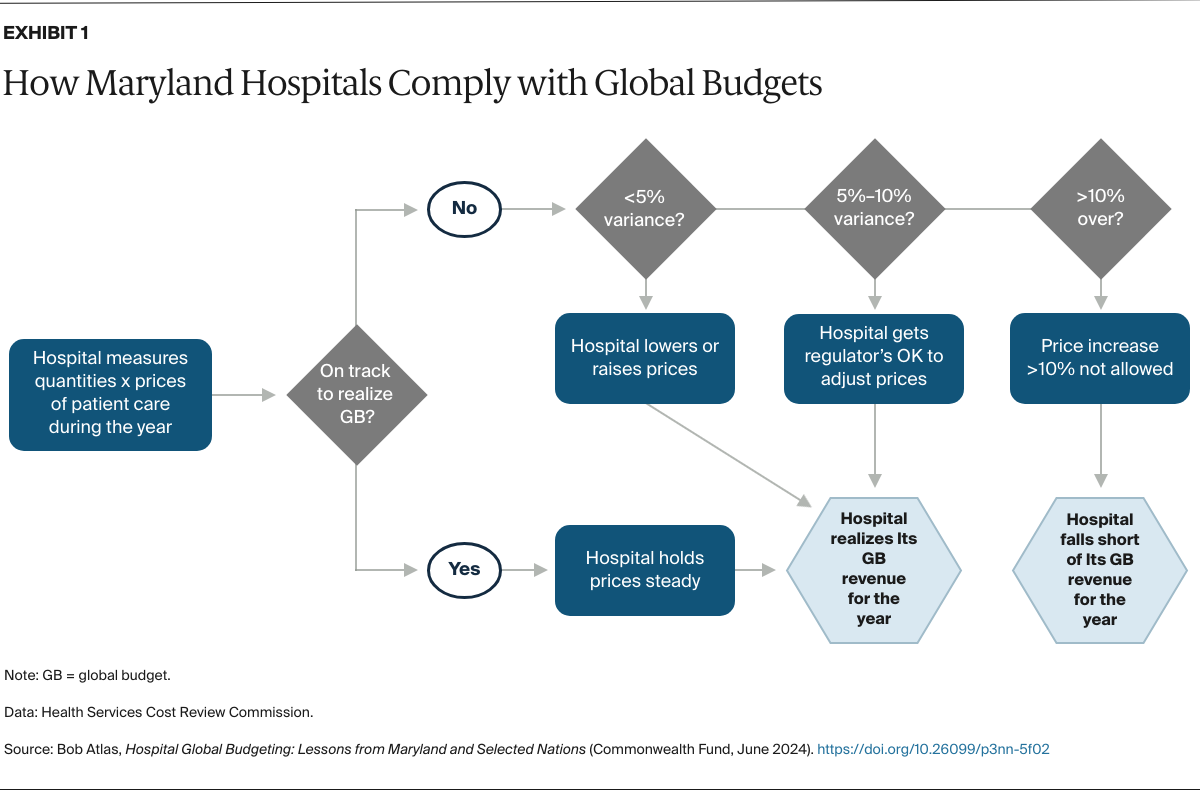

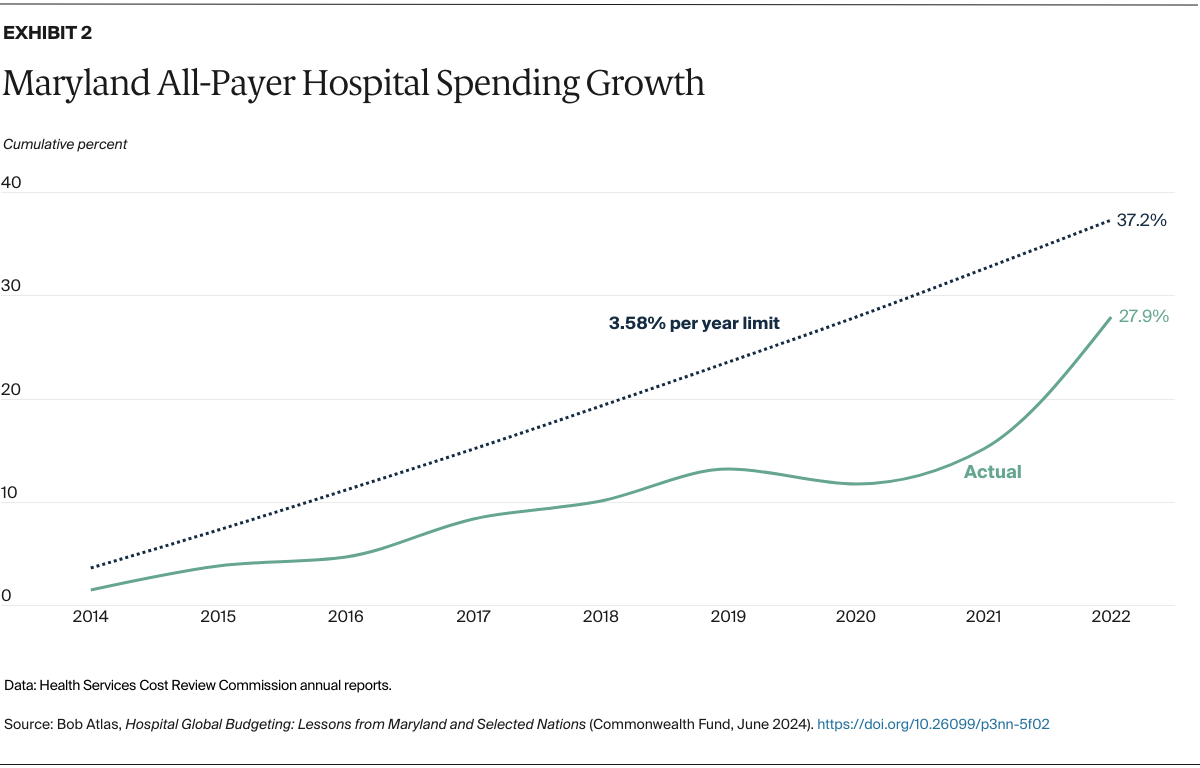

For the past 50 years in Maryland, a state commission has regulated hospital prices as if it were a single payer, despite the state’s multiplicity of payers. For the past decade, it also has set hospital global budgets. It also regularly introduces new policies, many that change the outcome of the global budget, to improve patient satisfaction and quality of care or to reduce emergency department overcrowding. And five years ago, a small amount of risk, just 1 percent of a hospital’s Medicare revenue, was added to motivate hospitals to control nonhospital spending.

The Maryland model has some distinctive wrinkles, which may also manifest in the other countries. First, individual hospitals that believe their global budgets are unfavorable can appeal their global budget in whole by filing a “full rate application” with the commission. Or they can ask the regulator to recognize certain extraordinary costs incurred to protect patients’ access to vital services.

At the same time, however, if a Maryland hospital begins to appear redundant, such as if utilization falls and there is another hospital nearby that could meet all the community’s needs, there is little incentive for the owner to downsize or close the facility. Doing so amounts to giving up revenue that is virtually guaranteed.

Perhaps the most prominent feature all five systems have in common is a constant drive for change. Every one of these payment systems has undergone major modifications since the beginning of this century, and all are continually scrutinized for opportunities to do better.

Financial sustainability is a key driver of change, whether for the funder or the hospitals, or both. Access to quality care for all residents is another motivator — concerns arise everywhere about patients’ long waiting times, growing travel distances for specialized care, and slow adoption of worthy technological innovations. Leaders broadly also recognize the importance of keeping the population healthy and changing the focus away from the curative care model.

Lessons for U.S. Policy

The U.S. government right now is grappling with issues related to patient access, population health, and financial sustainability, as are many states. In a recent publication pertaining to the AHEAD model, CMS gave this rationale (paraphrased) for promoting global budgeting wherever hospital revenue is now tied to fee-for-service payment:

Global budgets are a critical tool for containing cost growth, improving hospital quality, and generating revenue needed to invest in population health, primary care, behavioral health, and health equity. Where fee-for-service may promote overuse of services, duplication of complex services, or overinvestment in facilities and technology, global budgets give hospitals — including rural and urban safety-net hospitals — financial stability and flexibility. Global budgets also encourage hospitals to reduce avoidable care and to join with other health care providers and public health agencies to improve the health of the populations they serve.20

Our observations on several hospital global budgeting systems do not conflict with that rationale. However, our assessment also provides several considerations for next-generation global budgeting models:

- Global budgeting models must be simple and comprehensible for providers. Incentives do not work if the institutions and the people whose conduct is supposed to change cannot appreciate the benefits of making the change. This is especially true in the postpandemic era, when tightened resources and higher workforce turnover cut into opportunities for learning and change management.

- Choosing the right services to include in the global budget is important for promoting desired outcomes. Whether to put certain physician specialties and services in the global budget is a crucial decision. It affects whether providers who make clinical choices and perform procedures are aligned with those who manage resources.

- Thanks to technological advancements, many services that hospitals provide can be delivered no less safely in freestanding ambulatory care settings and even at patients’ homes. Global budgeting systems must be refreshed continually to reflect such changes.

Conclusion

Global budgeting can be a powerful tool for controlling hospital spending growth, encouraging preventive care in favor of acute curative care, and assuring hospitals of predictable revenue streams. Policymakers, however, will need to consider real differences between hospitals, including their varying capabilities and the distinct health needs of the populations they serve. And they will need to prevent free ridership by hospitals that find themselves advantaged not by doing better but simply by the way the rules work.