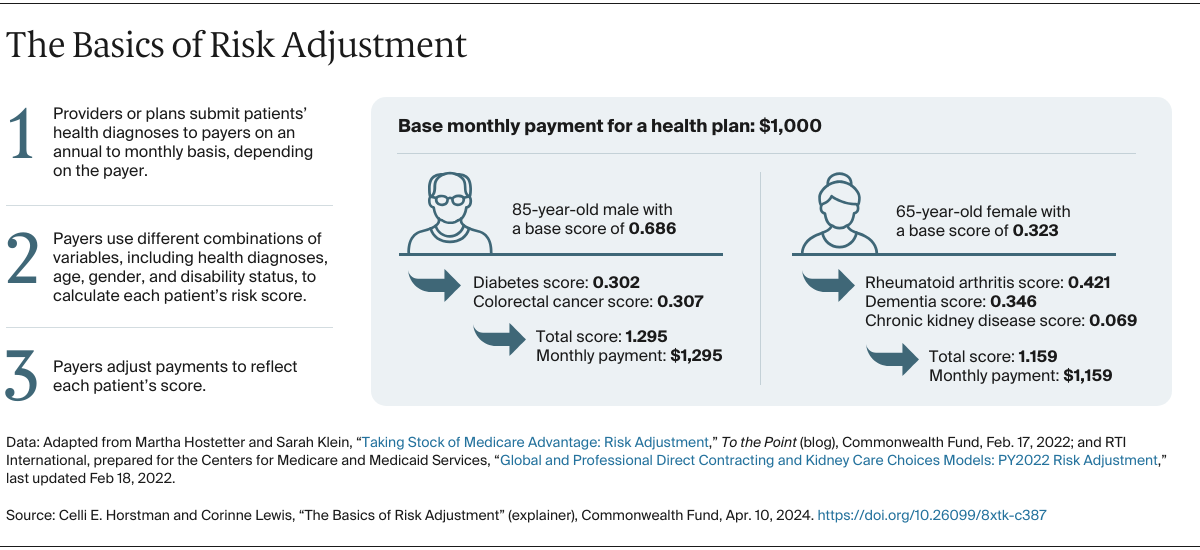

Risk adjustment methods vary across payers and programs. For example, state Medicaid managed care programs choose which statistical model to apply, which patient health factors to consider, how frequently risk scores are updated, and how to account for new enrollees without documented health information. Meanwhile, in Medicare Advantage, payments are adjusted annually, and plans use the same statistical model and set of risk factors. There are also other adjustments for Medicare Part D and for patients enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid.

Risk adjustment assumes that all data are complete, accurate, and consistent. But that may not be the case for all patients, and coding practices may be inconsistent across plans. This can make it challenging to arrive at accurate and properly adjusted payments.

What factors into risk adjustment?

Risk adjustment traditionally uses a limited set of characteristics to predict the cost of a patient’s care, including age, sex, and chronic health conditions. Social drivers of health, like having stable housing and food security, have historically not been included in risk adjustment models, even though there is extensive evidence of their impact on health care costs and outcomes. This is largely because of a lack of accurate, standardized data.

Some payers and policymakers, however, are considering incorporating social drivers of health in risk adjustment. They say that since it’s more expensive to treat patients with social needs, providers may not have adequate financial resources to care for them without risk-adjusted payment. In the United States, providers treating a greater share of patients with social needs report worse quality outcomes and face larger financial penalties than providers treating a smaller share of these patients. In the United Kingdom — where capitated payments, particularly for primary care, have been common for years — provider payments are lower in socially disadvantaged areas, partly due to the exclusion of individual social risk factors. These lower payments have contributed to regional provider shortages and inequities in access to care.

Some payers and policymakers have considered whether risk adjustment should also incorporate race and ethnicity, as these individual patient characteristics are associated with health inequities. However, this information is not systematically collected by health care delivery systems and providers in the U.S., and adjusting based on incomplete data could simply mask existing inequities. For example, research has shown that people of color face structural barriers to accessing health care, which may result in decreased use of services. In turn, this leads to lower risk scores and payments, which may not accurately reflect patients’ true health needs. Inclusion of these factors would also likely lead to legal challenges, given that resources would likely shift from one racial or ethnic group to another.

How could risk adjustment account for the social drivers of health?

There are two ways. First, risk scores could rely in part on individual-level measures, like information on social needs that patients self-report. Individual measures like chronic conditions are already incorporated in traditional risk adjustment. The problem is that providers are not collecting these data in a consistent way. Some experts are also concerned that this approach could reduce payments to providers treating a greater share of patients with social needs. That’s because even though social needs are associated with worse health outcomes, they often are also correlated with reduced use of health care. When predicting these patients’ future care needs, individual-level models could therefore underestimate future spending and reduce payments accordingly.

Community-level measures of social risk or social deprivation, which are used to adjust risk scores to reflect social needs within the patient’s community, are often viewed as more actionable and appropriate. This is because validated data, such as U.S. Census data, are readily available. Community-level measures have already been successfully added to risk adjustment methodologies, including in Massachusetts’s Medicaid program and Maryland’s all-payer program. However, community-level measures may be less precise than individual-level measures in predicting the relationship between health care outcomes, costs, and the drivers of health.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center is piloting a community-level social risk adjustment model. Under this model, providers treating a larger share of patients with social needs receive an additional payment, and those serving fewer such patients receive a lower additional payment.

When carefully designed and implemented, social risk adjustment may support providers that treat a greater share of patients with social needs. Experts say one of the keys is to set payments high enough to address not just the health effects of social needs but also the social needs themselves — without creating additional burden for providers. And while social risk adjustment is important to advancing health equity, it is just one part of using payment for this purpose.

Are there potential drawbacks to risk adjustment?

While necessary, risk adjustment could exacerbate inequities, particularly those relating to income, if it’s not designed and implemented well. In many payment programs, providers can be financially penalized for not achieving specific outcomes, such as improvements in quality of care. To ensure fairness, quality measures could be adjusted so that providers serving patients with a higher risk score are granted more flexibility if they perform worse on certain measures. However, this may have the unintended effect of incentivizing the provision of poorer care for higher-risk patients, instead of ensuring they receive additional, appropriate care. Experts recommend that risk adjustment for quality be done carefully, if at all, and applied only to limited metrics.

Another potential drawback is that risk adjustment can be gamed by plans and provider organizations to increase revenue. There is some evidence that plans and providers, particularly in Medicare Advantage, are intentionally “upcoding” — reporting that their patients have health issues more severe than they actually are — in order to receive higher payments for them. CMS is attempting to address this in two ways: by implementing stronger auditing rules, which will allow them to collect funds from insurers that inaccurately code patients’ health, and by reducing the number of chronic conditions that can be included in risk scores.