Introduction

Elderly patients with complex care needs may receive services from multiple specialists, as well as primary care physicians. In addition, they may visit emergency departments, have frequent hospitalizations and post-hospital rehabilitations, and receive long-term care services at their home or in nursing facilities. Jönköping County in Sweden focused on improving care coordination and the experiences of elderly patients through the “Esther model.” This case study describes the model and summarizes available evidence about its impact based on published materials and interviews with program leaders in Jönköping and Stockholm.

Care coordination in Sweden is complicated by a legal structure that gives the country’s 21 counties responsibility for funding and providing hospital and physician services while the 290 municipalities are responsible for funding and providing community care. Home health care — largely nursing services for sick patients — and home care (e.g., assistance with activities of daily living) are provided by different professionals.

The Esther model was developed in the Höglandet (Highland) region (population: 110,000) to improve the care of elderly people with complex conditions. Its operation is coordinated at Qulturum, a center in in Jönköping County that focuses on improving care and developing innovations for patients, as well as on work flow, teams, leadership, management, and health care design.1

The Esther model began in the late 1990s, originally as a three-year project. Founder Mats Bojestig,2 then head of the medical department of Höglandet Hospital in Nässjö, used the negative experiences of an elderly patient, known as “Esther,” as inspiration. Esther’s experience, as described by Nicoline Vackerberg, coordinator of the Esther model, is as follows:

|

ESTHER LIVED ALONE and one morning developed breathing difficulties. After contacting her daughter, who did not know what to do, Esther sought medical advice. She was seen by a district nurse and told to visit her general practitioner (GP). The GP said she needed to go to hospital and called an ambulance. After being admitted to emergency care she retold her story to a variety of clinicians at the hospital during a five-and-a-half-hour wait. Esther saw a total of 36 different people and had to retell her story at every point, while having problems breathing. This process caused Esther to become confused. (In a worst-case scenario, she could have been misdiagnosed with dementia). After her long wait, a doctor finally admitted her to a hospital ward and treatment began.3 |

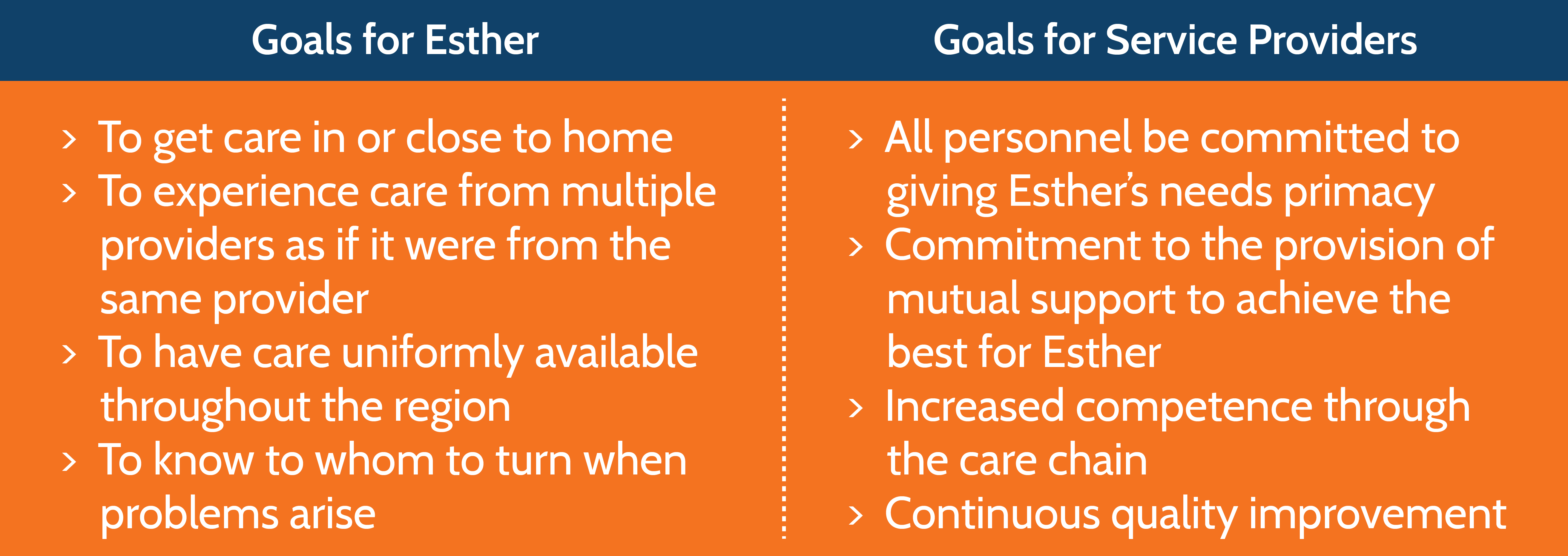

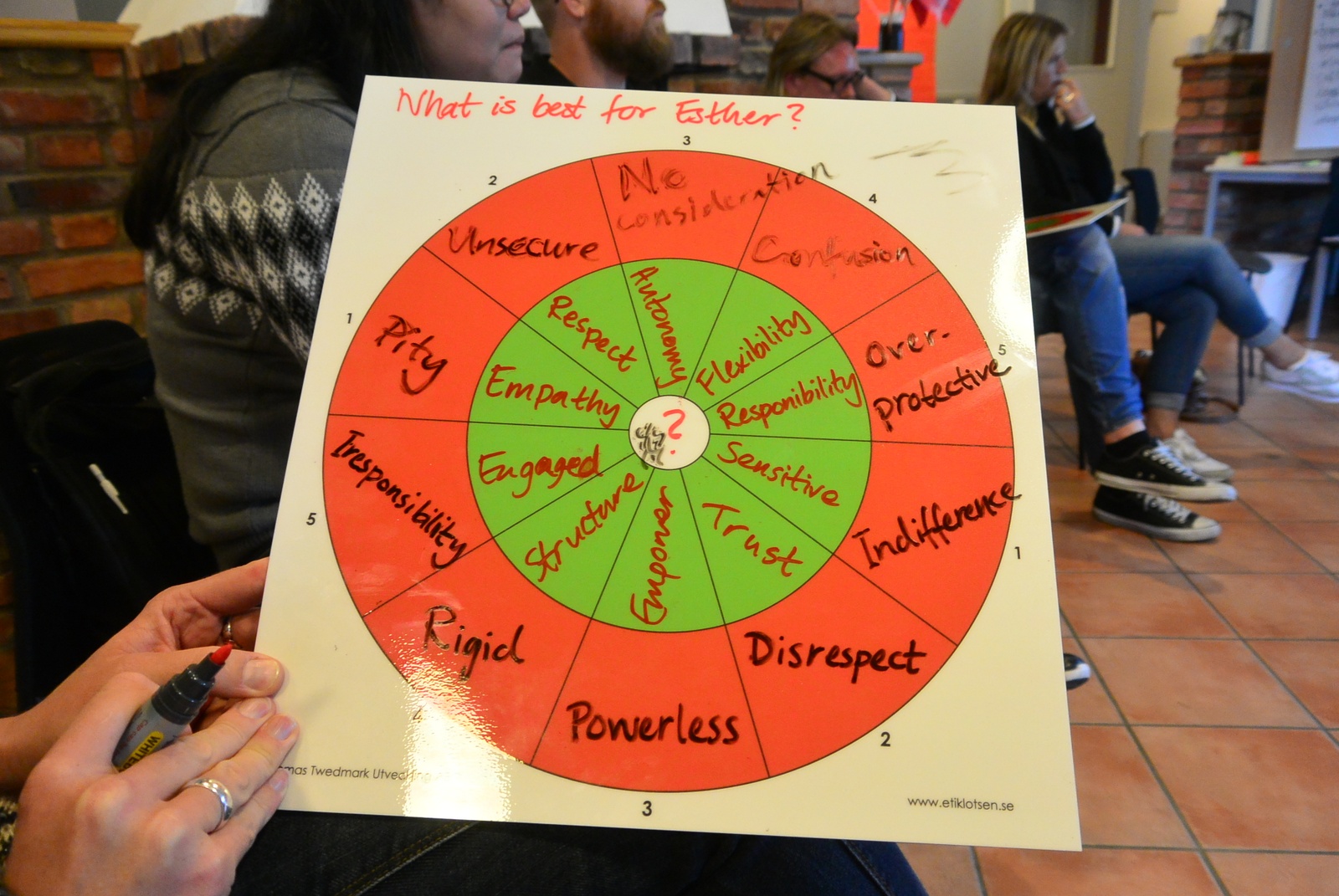

With Esther’s experience in mind, Bojestig initiated an extensive series of interviews and workshops between 1997 and 1999 to identify redundancies and gaps in the medical and community care systems and develop an action plan for improvement. “Esther” came to represent elderly persons who have complex care needs that involve a variety of providers. Creating a persona for the patient helps caregivers focus on the needs, preferences, hopes, and concerns of real people who need care. The central idea was that care should be guided by the following questions: What does Esther need? What does she want? What is important to her when she is not well? What does she need when she leaves the hospital? Which providers must cooperate to meet Esther’s needs?

The main focus, however, is determining, “What is best for Esther?” The Esther model uses continuous quality improvement, cross-organizational communication, problem-solving, and staff training to provide the best care for elderly patients with complex care needs.

Key Program Features

Interorganizational Mechanisms

Because many of the problems experienced by Esthers involve more than one organization, a central issue was how to bring together people from different levels at various organizations. Components developed include:

- A steering committee of the community care chiefs from municipalities, hospitals, and primary care centers to address challenges across organizations.4

- Four “Esther cafés” in municipalities each year. These are cross-organizational, multiprofessional meetings for sharing and learning from the experiences of specific patients who were hospitalized in the last year and have continued on to home care or other services.

- Interorganizational training workshops on palliative care, nutrition, and fall prevention, among other topics.5

- An annual “strategy day” in which nurses and other staff, physicians, managers, Esther coaches, as well as Esthers themselves come together to team-build and generate priorities and ideas for addressing problems in care.

All meetings involve at least one Esther to be sure that the patient’s perspective is included. The model is a collaboration of organizations that participate voluntarily as equals. Coordinators at Qulturum facilitate the various activities, but there is not a hierarchical structure and no single organization has ownership of the process.6 The idea that Esther is cared for by a network of organizations is essential to addressing the care problems that can arise when multiple organizations are involved. Organizations caring for an Esther should not only focus on the services they provide but also think about who the next provider will be and what needs to be conveyed to smooth Esther’s movement through the care chain.

Esther Coaches

In 2006, the program began to train “Esther coaches” — clinical and administrative staff members (i.e., not managers) from the participating organizations. Coaches are most commonly nurse assistants and nurses, but they also include physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and administrators. Coaches are not paid extra — the work is part of their jobs. To become a coach, employees receive eight days of structured training over eight months in problem analysis, quality improvement, and client focus.

The energy in the Esther model comes from the coaches, said Vackerberg.7 In their organizations, coaches are expected to support improvement projects at the frontline, introduce ideas to improve competencies, make connections between daily work and performance improvement, inspire and motivate colleagues to improve, and introduce “lean thinking” — that is, using the right resources in the right place at the right time to minimize waste, retain flexibility, and make workflows smoother.

Organizational Changes

The Esther model has resulted in many change over the years.8 For instance, transitions have been streamlined through telephone and email communication between patients’ primary care physicians and hospital-based specialists to allow patients to be admitted directly to a ward rather than through the emergency department. Hospital discharges have been improved by giving patients a “safety receipt” that includes a checklist of items that hospital personnel are supposed to review with the patient. This document is also used to convey information to organizations that provide other health care and social services to the patient.

In addition, there is now systematic follow-up within 72 hours of patients being discharged from the hospital, and patients have a care plan and a designated GP. Patients receive a “Welcome Back Home” package from municipal social care staff. Staff members are present when patients return home from the hospital to make sure everything is in order — that there is food, a clean bed, the right equipment and medication, and a personal wrist alarm, if needed. Special attention is paid to the needs of “focus patients” — that is, those who have had three or more hospital admissions in a year or for whom personnel have a gut feeling they will return to the hospital.

A “virtual competence center” is used to transmit knowledge to practitioners along the care chain.9 For example, individual professionals can sign up for online workshops on topics such as dementia or palliative care. Evaluations by participants found that use of the center strengthened teamwork and staff members’ understanding of different roles in the care chain.10

Results

We must be cautious in assessing the impact of the Esther model. It was not designed as a research project and involved many organizational and process changes that were introduced in different components of the model at different times. Positive changes are noted, but it is difficult to attribute them to the Esther model in the absence of comparative information.

With these caveats in mind, program leaders cite the following outcomes:

- Admissions to the medical department of Höglandet Hospital declined from 9,300 in 1998 to 6,500 in 2013.11 Hospital days in the medical and geriatric ward declined from 48,222 in 2002 to 44,769 in 2013. However, similar changes were reported elsewhere in Sweden.

- Hospital readmissions within 30 days for patients age 65 and older dropped from 17.4 percent in 2012 to 15.9 in 2014. In the community of Tranås, where a new “Welcome Back Home” package was introduced for discharged patients, the readmission rate dropped to 12.1 percent in 2014.12

- Hospital lengths of stay decreased between 2009 and 2014 for surgery (from 3.6 to 3.0 days) and rehabilitation (from 19.2 to 9.2 days). Shortened hospital lengths-of-stay was a general trend in Sweden, but the rehabilitation change was a response to a specific effort within the Esther model to move rehabilitation into or close to the patient’s normal environment.13

- Surveys conducted in Jönköping in 2008 and 2011 showed that Esthers felt safe and were appreciative of the personal contacts.14

Challenges

Making frontline personnel into agents of change by empowering them with a vision and knowledge of quality improvement tools can create tension. For instance, if changes are made in a particular service component without the advance knowledge of organizational leadership, leaders may be caught off guard.15 Leaders play a big role in generating change: supportive leadership can bring about positive changes, while conservative, hierarchical leadership can block changes that would benefit Esthers. Model leaders encourage organization heads to commit to supporting changes proposed by the Esther coaches, but such commitment cannot be forced, and there is a general tendency for organizations to return to their traditional attitudes and practices.16

Privacy laws that limit information-sharing by hospitals and the organizations that provide home and nursing home care also pose problems. However, with an Esther’s consent, professionals can use an electronic communication system to share admitting, discharge, and care planning information across boundaries.

Maintaining an adequate budget has proved difficult. The budget was 1.8 million Swedish kronor (about $300,000) in 2011, which covered the salary of the coordinators, education of the coaches, and new improvement projects.17 The current budget comes from the Jönköping County Council and covers meeting expenses and coach education. Coordinators are paid from their home organizations’ budgets.18

Potential for U.S. Replication

The Esther model developed as a voluntary collaborative effort in a small region that allowed for face-to-face meetings among all care-providing organizations. It is difficult to envision the model exported in its entirety to more complex settings. Nevertheless, many of its strategies are applicable well beyond a subregion of a Swedish county. In fact, cousins of the Esther approach are now operating elsewhere in Sweden,19 and replication is occurring in locations in other countries as well.20

The problems that the Esther model addresses certainly exist in the United States, where the care chain involves multiple provider organizations and payers with conflicting financial incentives. Establishing Esther or a similar model in the U.S. might be most feasible in places where single organizations are responsible for multiple levels of care or where hospitals serve reasonably well-defined geographic regions. Mechanisms that consolidate economic and medical responsibilities for patients, like accountable care organizations, would likely facilitate adoption of the model, as would financial incentives that deter practices that are harmful to patients and wasteful of resources, like unnecessary hospital readmissions. Adoption also might be aided by continuing to survey patients and caregivers about the care they are receiving.

In the U.S., the model could perhaps shift from the question ‘What is best for Esther?’ to simply asking Esther what she believes would be best for her.

According to Eric Coleman, M.D., M.P.H., director of the Care Transitions Program at the University of Colorado Denver, the Esther approach not only represents an innovative approach to coordination across care settings but addresses another element of care that the U.S. struggles with: operationalizing person-centered or person-directed care. Coleman believes that in the U.S., the model could “perhaps shift from the question ‘What is best for Esther?’ to simply asking Esther what she believes would be best for her.”

Importing the model to the U.S. would require the willingness of health care leaders to make “high-level organizational commitments and long-term investments of substantial interorganizational quality improvement resources,” says Chad Boult, M.D., medical director of geriatrics and palliative care at Saint Alphonsus Healthcare System. In turn, this willingness would depend, he says, on the “allure of financial incentives” and the belief in “substantial economic benefit by collaborating with others, such as participants in some value-based contracts.”

Numerous “cousins” of the Esther approach are currently being tested in communities throughout the U.S., notes Mary Naylor, professor of gerontology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. She believes that sharing lessons from these “islands of innovation will accelerate the movement toward the person-centered, seamless care system” that the Esther model strives for.

Conclusion

Taking a system approach to meeting the needs of the frail elderly is unusual, difficult, and necessary. The Esther model depends on what project leader Nicoline Vackerberg calls “the power of patients’ stories.”21 These stories, which are elicited and collected as part of the model, show how patients’ lives are affected by their health challenges and their experiences in getting care. The model also creates mechanisms, including the annual retreat and development of action plans for the forthcoming year, to help members of different professions think together to solve problems and help to motivate coaches.