Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder with no known cure. There are an estimated 630,000 to almost 1 million people with Parkinson’s in the United States.1 The number of cases may double by 2040, as the population ages.

Early symptoms include barely noticeable tremors, but as the disease develops, patients experience problems that may include thinking difficulties, depression and other emotional changes, swallowing problems, sleep disorders, bladder problems, stiffness, blood pressure changes that may induce dizziness or lightheadedness (and associated risk of falls and hip fractures), smell dysfunction, fatigue, pain, and sexual dysfunction.2 Patient care focuses on quality of life and reduction in disability.3

Patients with degenerative chronic diseases like Parkinson’s require specialty medical care, nursing, and various supportive services. Access to services can be difficult and available personnel do not necessarily have disease-specific expertise. In addition, the standard of care can vary, and care coordination presents challenges.

Background

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder with no known cure. There are an estimated 630,000 to almost 1 million people with Parkinson’s in the United States.1 The number of cases may double by 2040, as the population ages.

Early symptoms include barely noticeable tremors, but as the disease develops, patients experience problems that may include thinking difficulties, depression and other emotional changes, swallowing problems, sleep disorders, bladder problems, stiffness, blood pressure changes that may induce dizziness or lightheadedness (and associated risk of falls and hip fractures), smell dysfunction, fatigue, pain, and sexual dysfunction.2 Patient care focuses on quality of life and reduction in disability.3

Patients with degenerative chronic diseases like Parkinson’s require specialty medical care, nursing, and various supportive services. Access to services can be difficult and available personnel do not necessarily have disease-specific expertise. In addition, the standard of care can vary, and care coordination presents challenges.

Parkinson’s Care in the Netherlands

In the Netherlands, about 50,000 people have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.4 While all have health insurance through one of several nonprofit companies, they must contend with the Netherlands’ complex health care delivery system. General practitioners (GPs) make referrals to neurologists when symptoms of Parkinson’s appear. Care may include medications, surgery, and referrals to allied health professionals such as physiotherapists for supportive services. GPs, however, continue to address patients’ general health care needs.

Care coordination is not a billable service and is thus not routinely provided. Service providers may be salaried hospital employees or self-employed and paid on a fee-for-service basis. The various providers do not have access to a shared electronic medical record. No one provider is responsible for outcomes.

Focus groups and online patient forums in 2004 showed that PD patients were often dissatisfied with their care.5 They complained of treatment that focused exclusively on suppression of symptoms with drugs or neurosurgery, referrals to allied health professionals (e.g., physical or occupational therapists) and care management approaches that seemed arbitrary, and difficulty identifying allied health professionals with PD expertise.

Patients also complained about not being involved in treatment decisions, receiving insufficient attention to quality-of-life concerns, and experiencing a lack of coordination and communication among their various providers.6

The problem of coordination and communication was less severe among health professionals who had higher caseloads of patients with PD.7 However, a 2008 survey found that, on average, allied health professionals treated only three PD patients a year.8

Development of ParkinsonNet and How It Works

ParkinsonNet (PN) was created in 2004 by Bastiaan Bloem, a neurologist, and Marten Munneke, a physiotherapist, at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen after they concluded that the lack of PD-specific knowledge among allied health professionals along with an absence of practice guidelines was producing “unacceptable variations in the quality of care, with suboptimal health outcomes and high costs as a result.”9 ParkinsonNet was developed with the goal of providing the best possible care to PD patients and their families, with an emphasis on home- and community-based care. The program has since expanded to cover the whole country.

ParkinsonNet consists of a set of geographically based, multidisciplinary networks of allied health professionals who are committed to providing services to PD patients using evidence-based practice guidelines. The program is facilitated by an IT platform to which patients and their families have access and that enables the provision of quality-related feedback.

Using Multidisciplinary Networks of Health Professionals

ParkinsonNet’s 69 regional networks include some 3,000 allied health professionals—primarily nurses and physical, occupational, and speech therapists—that are organized around hospitals. To be in a network, allied health professionals are required to receive training in care of PD patients and pay an annual membership fee (115 euros) that helps defer the costs of the Radboud national coordination center. The networks also include neurologists,10 nursing home physicians, rehabilitation specialists, psychiatrists and psychologists, pharmacists, social workers, and sex therapists. Local coordinators—generally nurses or physical therapists—tend to the network and organize local educational programs.

The networks were developed as a way to implement evidence-based practice guidelines, increase patient volume (and, thus, experience) for professionals serving PD patients, and support communication among those professionals. They serve as a resource for neurologists and other health professionals, as well as for PD patients and their families.

The creation of evidence-based practice guidelines for allied health professionals was an important early step in the program’s development. The guidelines are based on systematic reviews of research evidence and clinical experience. The guidelines are discipline-specific and include advice for physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, dietetics, nursing, and nursing homes.

To be selected for PN, allied health professionals must be committed to the care of Parkinson’s patients and be willing to follow PN’s practice guidelines and collaborate with the professionals, patients, and families in the PN community. Multidisciplinary training sessions cover general information about Parkinson’s disease, the patient’s perspective, types of services patients may need, and interdisciplinary communication and collaboration. There are also discipline-specific sessions on topics like skill development and the use of practice guidelines. Nurses can complete a 10-day course to become a certified Parkinson’s nurse.

New scientific knowledge is built into updates of the practice guidelines and annual educational programs and is disseminated to professionals, patients, and families via PN’s information platform.11

Information Technology

ParkinsonNet’s information technology platform includes a dedicated website (www.ParkinsonNet.nl) with a search engine that enables patients to identify conveniently located professionals and view their PD-specific expertise. Patients and professionals also can participate in web-based communities. In addition, there is a decision-support tool that allows patients to find information about the disease and treatment options, which helps them make informed decisions about their care as the disease progresses. An additional tool provides patients the chance to build their own virtual network of care providers, encouraging information exchange and collaboration.12

Quality Improvement Registry

ParkinsonNet launched a national quality registry in 2015 in collaboration with neurology and Parkinson’s patient associations. The registry, which was in part a response to some patient complaints that the PN label did not assure quality, collects patient-specific information from neurologists about patients’ health status, outcome indicators such as hip fractures, and structure indicators such as the presence of a Parkinson nurse.13 In addition, patients are asked to complete questionnaires about their quality of life and their health care experiences, using a consumer quality index that the ParkinsonNet team developed. This tool was also validated in the United States and Canada.14

The registry allows professionals to add information relevant to their discipline. Initial resistance from neurologists declined after the data entry requirement was lessened from every visit to once per year for each patient; 75 percent of neurologists now participate.15 More than 5,000 patients have been entered into the registry. The registry will enable ParkinsonNet to offer regional teams feedback about the cost, quality, and outcomes of care. Comparisons across regions will enable teams to identify and learn from best practices.16

Impact of ParkinsonNet

ParkinsonNet is the best example I’ve seen anywhere in the world that turns the transformational idea of interdisciplinary, team-based care focused on improving health into action.

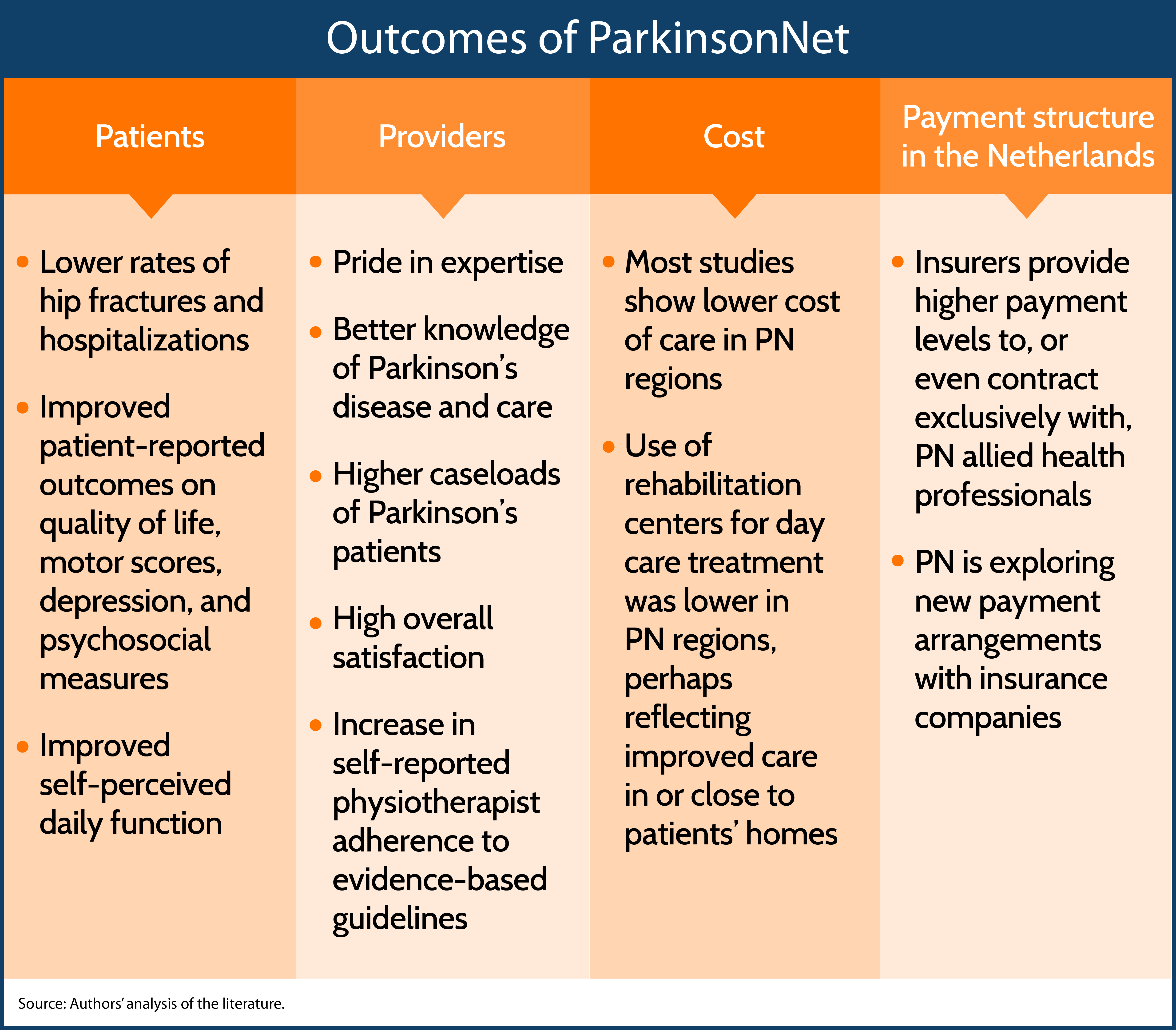

ParkinsonNet now covers the entire country. From 50 percent to 70 percent of Parkinson’s patients use physical, occupational, and speech therapists from a PN network.17 With its emphasis on nonpharmacological, multidisciplinary care in home and community settings, ParkinsonNet has changed the care that patients receive and the experience and expertise of the health professionals who provide care. For example, an observational study of physiotherapists in the first PN network showed their caseload of PD patients increased from 8.1 to 17.6 between 2003 and 2006 and that they had more PD-specific knowledge.18 PN’s annual survey of its health professionals found they “take pride in being recognized as experts in the disease and value being part of a professional network with similarly interested colleagues with whom they can communicate easily.”19

ParkinsonNet is also viewed positively by patients. Feedback from patients has been collected via focus groups, patient-experience questionnaires, and in web-based communities.20 A recurrent theme is the fact that patients value the ability to be seen by trained experts who understand the complexity of their condition. Most patients appreciate being able to identify these experts using the web-based search engine because it allows them to select experts who fit their needs.

ParkinsonNet also provides a platform to test innovative approaches for providing services. Trials have focused on several components of PN care, including:

- Occupational therapy: A randomized trial found that occupational therapy improved self-perceived daily functioning among patients,21 and while no significant impact was shown on total costs, caregivers experienced significantly reduced costs.22

- Multidisciplinary care: A randomized trial comparing care by multidisciplinary or specialist teams with standard care by a neurologist showed that the multidisciplinary teams had significant positive outcomes on several patient-reported measures: quality of life, motor scores, depression, and psychosocial dimensions.23

- Community-based networks: Comparison of PN network areas with randomly selected areas with no PN revealed no differences in disability and mobility outcomes, but costs were lower in the PN areas.24

There is additional evidence of cost savings with the PN approach. The Radboud group compared the care of 150 patients in two hospitals using the PN model to 151 patients in four hospitals that provided usual care. Though no differences were found on measures of disability and quality of life, costs of the interdisciplinary approach were substantially lower over the eight months of the study (489 euros vs. 1,950 euros).25

An observational study by KPMG compared insurance claims in 2009 in regions with and without ParkinsonNet and found that patients in PN regions were more likely to receive physiotherapy and were 55 percent less likely to suffer a hip fracture (a proxy measure for falls).26 Costs per patient were substantially lower (640 euros in 2008; 391 euros in 2009) in the PN regions.

Such savings have led to changes in the way care is paid for. Some insurers provide higher payment levels to or contract exclusively with PN health professionals. However, this has raised some concerns among patients with relationships with non-PN providers. Registry information could allow health insurers to tailor reimbursement levels to networks that offer the greatest value to patients, a possibility that has been challenged by some neurologists.

The way care is organized and financed in the Netherlands does not fit well with PN’s goal of having Parkinson’s patients cared for by integrated teams of practitioners who provide evidence-based care. A better model than paying various care providers on a fee-for-service basis, according to Bloem and some insurers, would be an annual capitation fee for PN patients along with a case manager—ideally a Parkinson’s nurse—to ensure appropriate, integrated care. At present, there are no financial incentives for keeping patients out of the hospital, as PN seeks to do. PN is working with insurance companies to experiment with new payment arrangements, like finding ways to base payment on outcomes. Outcome measures developed with the Dutch Association of Neurologists are now being collected (to some extent) at all hospitals that provide Parkinson’s care. These include: falls with injury; unplanned hospital admissions; hospital admissions for pneumonia; patient-reported quality of life using a special Parkinson’s scale; patient-reported experience measures, such as quality of coordination of care and communications with physicians; and total cost of Parkinson’s-related care. At present, outcomes-based payment is only being used at the Radboud medical center where ParkinsonNet was developed.

ParkinsonNet has been financed thus far by a combination of grant funding and experimental arrangements with insurance companies. The ongoing operation of PN costs about $150 per patient per year. But although research has shown and insurers believe that PN produces even greater cost savings because of lower rates of fractures and hospitalizations, the services that PN provides are not reimbursable as medical expenses.27 However, ParkinsonNet has a high profile and strong support among insurance companies and the government, so avenues for stable funding may be found.

Conclusion

ParkinsonNet has evolved from a way to improve care provided by physical therapists into a national transformation in PD care by creating multidisciplinary regional care networks, using information technology, empowering patients, facilitating clinical research, and implanting quality improvement tools.

Long-term financial stability for PN will require changes in how care is organized and paid for. Ideally, all caregivers would be covered by one annual payment rather than separate fee-for-service payments. Such a change would be politically difficult, but its feasibility may be enhanced by the evidence that patients in PN have fewer falls and fractures and lower rates of hospitalization.

The ParkinsonNet approach is being adopted in other countries. In the United States, Kaiser Permanente is implementing PN. Capitation that covers the services provided by Kaiser Permanente’s salaried professionals reduces the health system headwinds that PN has faced in the Netherlands. Amy Compton-Phillips, M.D., executive vice president and chief clinical officer at Providence Health and Services in Seattle, hopes the model continues to replicate. “ParkinsonNet is the best example I’ve seen anywhere in the world that turns the transformational idea of interdisciplinary, team-based care focused on improving health into action,” she said. “As the U.S. starts to move away from fee-for-service toward value-based care, the structural barriers preventing spread to the U.S. are coming down. I’m hopeful we’ll see successful prototypes stateside in the near future.”

In addition, the Netherlands is developing in ParkinsonNet-like approaches for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and dementia—other conditions in which patients see multiple types of care providers.

Parkinson’s disease remains a terrible, progressive disease for which there is no cure, but there is evidence that the ParkinsonNet approach can positively affect the functioning and quality of life of patients, reduce the incidence of negative events like falls, enhance the professionalism of allied health providers, and save money.