In August 2022, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, giving the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) the authority to negotiate prescription drug prices for certain high-cost drugs in Medicare. When this provision takes effect in 2026, it will mark the first time the federal government has negotiated with drug manufacturers.

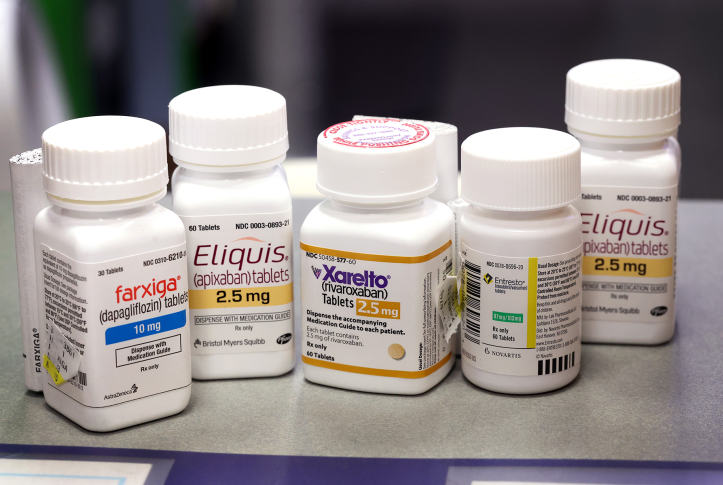

Recently, CMS selected the first 10 drugs for negotiation based on criteria outlined in the law. The agency will now begin collecting data and information from drug companies, clinicians, researchers, and the public to inform CMS’s initial offer prices to manufacturers for each of the 10 drugs. CMS will determine the starting point using information on therapeutic alternatives — that is, different drugs or therapies that have a similar clinical effect or benefit. The agency will first look at therapeutic alternatives in the same drug class (based on “properties such as chemical class, therapeutic class, or mechanism of action”) before considering therapeutic alternatives from another drug class.

Building an Initial Offer Price Using Therapeutic Alternatives

CMS will develop its starting point for prices by determining the average 30-day Part D net price1 or the average sales price (ASP) of an identified therapeutic alternative. When there are multiple therapeutic alternatives, CMS will develop a range of alternative Part D net prices or ASPs and select a starting point within that range. Once a starting point is determined, CMS will adjust it by analyzing clinical evidence to determine if the negotiated drug offers more, less, or similar clinical benefit compared to alternatives.

CMS guidance clarifies that information about therapeutic alternatives provides the agency with a starting point for determining an initial offer price. Once that is determined, CMS will increase or decrease the offer price based on information from the drug’s manufacturer, such as the cost of producing and distributing the drug or the extent to which the manufacturer has recouped the costs of research and development.

When there is no therapeutic alternative, or if the therapeutic alternative price is greater than the highest price CMS is allowed to pay for a negotiated drug under the law (known as the “statutory ceiling price”), then CMS will determine a starting point based on two other federally recognized sources. These are the Federal Supply Schedule price, which is the price negotiated by the Veterans Administration, or the Big Four price, which is the maximum price manufacturers may charge the big four federal agencies (i.e., Veterans Affairs, the Department of Defense, the Public Health Service, and the Coast Guard). If those are above the statutory ceiling price, then CMS will use the ceiling price as a starting point and adjust it based on information provided by manufacturers.

Benefits of Using Therapeutic Alternatives in Medicare Drug Negotiation

By using data on therapeutic alternatives as the basis for an initial offer price, CMS is establishing a novel framework to systematically compare drugs based on their value.

Although the law does not permit the negotiation of prices for drugs with generic competition, under this framework CMS may be able to consider the price of generic therapeutic alternatives and use these generic prices to drive down the initial offer price of brand-name drugs selected for negotiation. This process not only achieves a primary aim of the statute — that is, to meaningfully reduce prescription drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries — but also helps quantify the clinical benefits of a brand-name drug compared to alternatives with an approved generic for Medicare beneficiaries and taxpayers.

This framework is reliable and applicable across many drugs. The law requires negotiated drugs to be on the market for at least seven years for small-molecule drugs (e.g., aspirin or penicillin) or 11 years for biologics — for example, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, such as Humira and Enbrel, used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. This will mean a total of nine (for small-molecule drugs) and 13 (for biologics) years including the two-year negotiation period.

Potential Challenges

CMS has only four months to collect and analyze the information it receives from drug manufacturers and other stakeholders, including data on therapeutic alternatives, to determine initial offer prices. This short time frame may pose challenges. CMS may be inundated with clinical data, as well as information from manufacturers and the public. It will need a process for acquiring data and identifying the most relevant submissions. At the same time, it will be incumbent on CMS to demonstrate that it has conducted a thorough and impartial review. Additionally, there is some question whether the agency’s initial focus on alternatives within the same drug classes could limit potential savings in negotiations because the brand-name drugs likely to emerge from this process may have similar prices. Time and implementation will tell if CMS has adequately managed these challenges.

Conclusion

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services must implement a novel program for prescription drug price negotiation under an abbreviated timeline, and the agency may face some challenges in the program’s early years. However, CMS’s decision to use information about therapeutic alternatives to inform negotiations can bring systematization and reliability to efforts to lower drug prices in the Medicare program.