Abstract

In addition to its expansion and reform of health insurance coverage, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) contains numerous provisions intended to resolve underlying problems in how health care is delivered and paid for in the United States. These provisions focus on three broad areas: testing new delivery models and spreading successful ones, encouraging the shift toward payment based on the value of care provided, and developing resources for systemwide improvement. This brief describes these reforms and, where possible, documents their initial impact at the ACA’s five-year mark. While it is still far too early to offer any kind of definitive assessment of the law’s transformation-seeking reforms, it is clear that the ACA has spurred activity in both the public and private sectors, and is contributing to momentum in states and localities across the U.S. to improve the value obtained for our health care dollars.

Overview

In addition to its more familiar health insurance coverage reforms, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) contains numerous provisions that directly target how health care is organized, delivered, and paid for in the United States. These provisions take aim at the well-known shortcomings of the U.S. health system, from the inefficiency and high cost of our predominantly fee-for-service system to the extreme variability in the quality of care patients receive from region to region.

Building on existing reform models in the private and public sectors, the law takes multiple, complementary approaches to addressing the health system’s longstanding problems. These center on:

- testing new models of health care delivery

- shifting from a reimbursement system based on the volume of services provided to one based on the value of care

- investing in resources for systemwide improvement.

With the Affordable Care Act now five years old, this brief reviews these approaches and reports on the early impact of specific reforms and initiatives for which reliable data are available. Because many of these provisions are still in the early stages of implementation and testing, it is difficult, if not impossible, to make any definitive assessment of their impact. Nevertheless, it is useful at the five-year mark to review some of the law’s delivery and payment reforms in some detail and reflect on the experience of patients, providers, and payers as these profound changes unfold.

New Models for Delivering Health Care

Accountable Care Organizations

An accountable care organization (ACO) is an entity formed by health care providers—from primary care physicians and specialists to hospitals and postacute care facilities—that agree to collectively take responsibility for the quality and total costs of care for a population of patients. Beginning in 2012, the ACA established the Medicare Shared Savings Program to encourage the development of ACOs. If participating ACOs meet quality benchmarks and keep spending for their attributed patients below budget, they receive half the savings that result, with the rest going to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which administers the program. To keep a larger share of the savings (up to 60 percent), ACOs can choose to participate in a “two-sided risk” model, whereby they must repay a share of losses if health care spending for attributed patients exceeds the budget target.

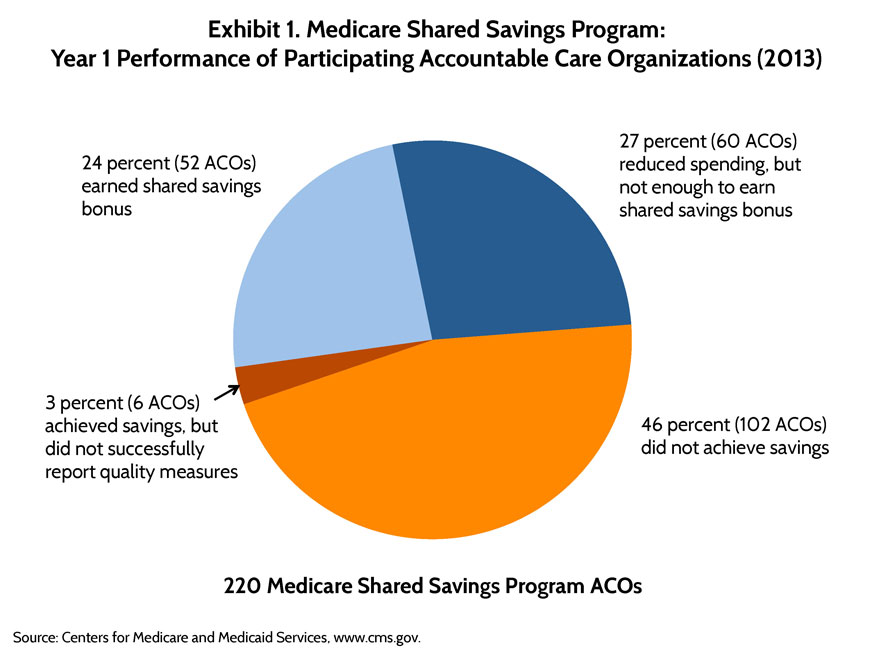

In 2015, there are more than 400 Shared Savings ACOs serving nearly 7.2 million beneficiaries, or 14 percent of the Medicare population. While these participation numbers have exceeded expectations, results from the program’s first year of operation, 2013, were mixed. Of the 220 Shared Savings ACOs that year, only 52 were able to meet quality-of-care benchmarks and keep spending below budget targets; these ACOs generated $700 million in total savings and roughly $315 million in shared-savings bonuses (Exhibit 1).1 Another 60 ACOs kept spending under their targets but either did not fulfill their requirements to measure the quality of care delivered to patients or did not reduce spending enough to meet the minimum criteria to share in savings.

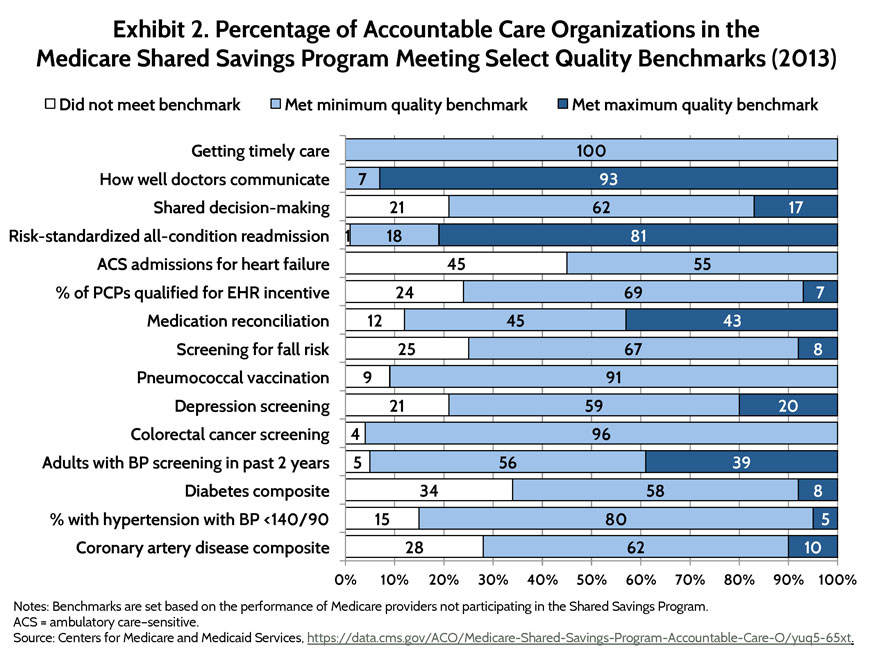

ACOs in the Shared Savings Program showed some improvement on most of the 33 quality measures—from diabetes care to depression screening—compared with other Medicare providers (Exhibit 2). However, these organizations were eligible to share in savings for simply reporting data on all measures, regardless of actual performance. Beginning in 2014, Shared Savings ACOs were required to meet minimum quality standards to qualify for a share in any savings, though performance data are not yet available.

The majority of the participating ACOs have opted for one-sided risk, which means they can share in savings produced but are not subject to paying a share of the losses incurred if spending exceeds targets. A key question for CMS officials is how they can sustain participation in the future while encouraging and supporting providers to assume greater financial risk. A global budget covering all patients is one potentially important strategy for encouraging clinicians to deliver care in innovative ways, invest in value-producing services that are generally not currently reimbursable (such as taking time to email or educate patients), and devote resources to infrastructure enhancements (such as information technology systems) that improve coordination with other providers.

However, most providers across the country have limited experience in managing care to a budget and limited capacity to coordinate care with other providers. Hence, many are not ready to take on the extra financial risk. For providers equipped to test more advanced payment models and stringent quality thresholds, CMS has launched the much smaller Pioneer ACO program, which is administered by the newly created Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Known as the CMS Innovation Center, this agency has the authority to test and nationally expand new models that are proven to reduce health care costs while maintaining or improving quality of care. The idea is that lessons learned from the Pioneer ACOs can be incorporated into the Shared Savings Program.

In the second year, 11 of 23 Pioneer ACO participants earned financial bonuses totaling $68 million, while three ACOs faced penalties of roughly $7 million. The Pioneer ACO that generated the most savings was Montefiore Medical Center, a safety-net system located in The Bronx, New York (read more about Montefiore’s experience here). Although Pioneer participants are considered among the most advanced ACOs, some have had difficulty meeting financial targets, and 13 have dropped out of the program as of March 2015, with most switching to the Shared Savings model.

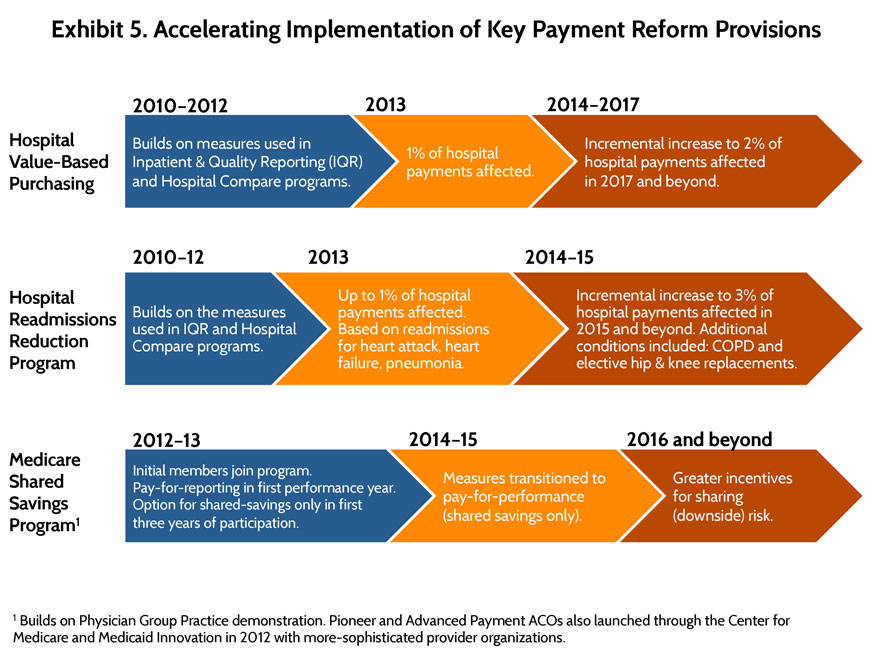

In recognition of the challenges providers face to be successful Medicare ACOs, CMS is allowing providers to take it slow by adopting the one-sided risk model for at least three years and by getting credit for simply reporting on quality measures in the first year. (See Exhibit 5 on page 8.) In addition, low-cost loans are being made available to help spread the model to smaller provider organizations and those in rural areas with limited start-up capital; in fact, one rural organization, Rio Grande Valley ACO, had achieved one of the highest levels of savings as of 2014. ACOs that have proved successful from the start tend to make investments in information technology systems, data analytic tools, and the necessary staff to identify high-risk patients and closely monitor their care.

Medicare’s ACO programs are likely to evolve with the accumulation of experience. An important marker of impact to watch will be whether ACOs’ investments improve outcomes for patient populations beyond Medicare.

Primary Care Transformation Through Implementation of Medical Homes

Although primary care is fundamental to a well-functioning health system, the U.S. has undervalued and underinvested in it for decades. The neglect of primary care is largely a byproduct of the prevailing fee-for-service reimbursement approach: providers have inherent financial incentives to favor higher-priced procedures over care management and other cost-saving services. As a result, the care U.S. patients receive is often poorly coordinated and expensive.

On the flip side, there is considerable evidence that comprehensive, coordinated, and well-targeted primary care can improve outcomes and reduce per-patient costs. These characteristics are embodied in the patient-centered medical home, a model of care that emphasizes more comprehensive care coordination, care teams, patient engagement, and population health management.

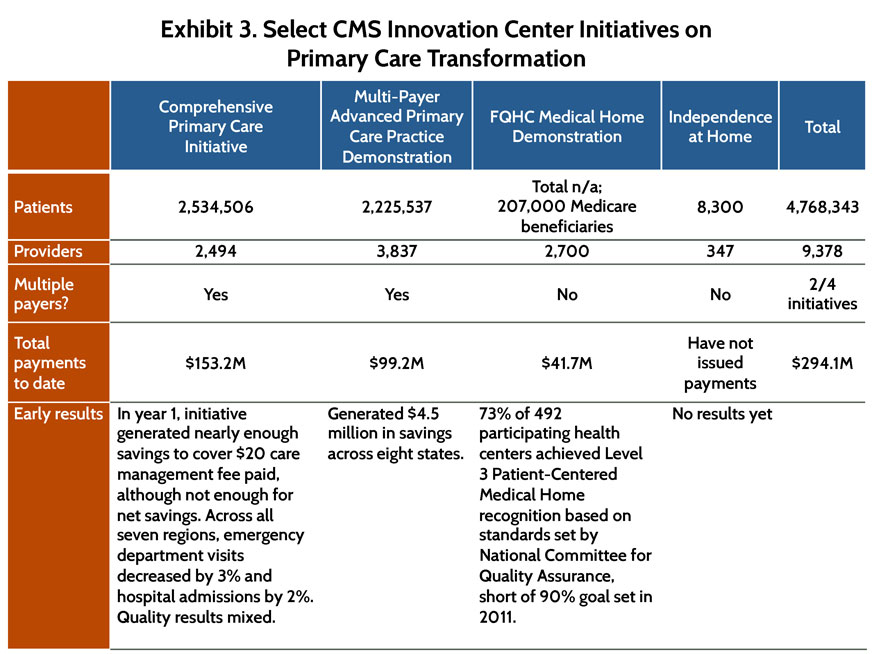

A number of the ACA’s reforms seek to transform primary care by way of the medical home model, through programs and initiatives involving private physician practices, community health centers, and even home-based care providers. The ACA also is helping health systems and states to experiment with ways to improve the quality of primary care, spread promising models, and integrate primary care more seamlessly with other health care services, such as behavioral health and long-term care services (see appendix for a summary of several primary care–related provisions in the law). Below we present recent findings from two of the CMS Innovation Center’s large-scale, multipayer primary care initiatives that seek to change the face of primary care in the U.S. (Exhibit 3).

Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative. This national initiative involving 29 payers (excluding CMS), nearly 500 providers, and some 2.5 million patients is testing a new way to deliver and pay for care that is designed to improve access, coordination, and chronic disease management while engaging patients and their caregivers. The program offers participating physician practices enhanced payment, technical assistance, and ongoing feedback on performance. Evaluation results show that in the initiative’s first year, spanning October 2012 to September 2013, the practices generated enough savings to cover most of the $20 per-member, per-month care management fee paid on average by CMS (although not enough to produce net savings overall). While there was considerable variation in performance among the seven participating U.S. regions, across all markets emergency department visits decreased by 3 percent and hospital admissions by 2 percent after year 1. Significant effects on quality were few.2

Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration. Medicare has joined eight state-sponsored pilot programs involving Medicaid and private insurers to test the impact of per-member, per-month fees paid to primary care sites for providing medical home services.3 In the demonstration’s first full year of operation, 2012, more than 3,800 providers in 700 practices serving 2.2 million patients participated. Recent evaluation results estimate $4.5 million in savings generated in year 1, translating to a return on investment of $1.35 for every $1 Medicare paid out. In Vermont and Michigan, growth in Medicare fee-for-service health care spending significantly slowed as hospital inpatient care expenditures fell. There is less evidence, however, that the state initiatives were able to reduce hospitalizations, readmissions, and emergency department visits.4

A major theme emerging from these efforts to transform primary care is the critical role of technical and financial support in building the capacity of physician practices to function as medical homes. Each of the ACA-supported transformation initiatives includes some level of support for practices to address common challenges. These include: collecting, reporting, and using data in a timely fashion for care management and quality improvement; changing the practice culture to enable effective teamwork; and obtaining information about patients from settings outside the practice.

In general, federal investments have stimulated unprecedented collaboration and dialogue among payers, both private and public, and providers on how to reorganize primary care at the local level to achieve the aims of reform. Still, Medicare, despite collaborating more actively with primary care providers and other payers since the ACA’s passage, needs to identify ways to share data more quickly with local partners and communicate programmatic changes clearly.

Reforming Provider Payment

The Affordable Care Act included many payment reform provisions aimed at promoting the development and spread of innovative payment methods to facilitate the adoption of effective care delivery models. The earliest of the ACA’s provisions related to provider reimbursement have slowed growth in fee-for-service payment levels. The intention was to provide some budget relief, particularly for the Medicare Trust Fund, and to send a clear signal to providers that they will need to adapt quickly to incentives that reward appropriate, high-quality care and good patient outcomes.

For example, reflecting the anticipated reduction in uncompensated care from increased insurance coverage, the ACA lowered annual increases in Medicare payment rates for hospitals and other facilities and explicitly set an expectation for providers to become more efficient over time. The law also reduced overpayments to private plans administering Medicare benefits through the Medicare Advantage program, bringing these payments more in line with traditional Medicare costs, and linked, as of 2012, plan payments to performance ratings and made the results public.5 Today, even with these lower payments, increasing numbers of beneficiaries are enrolling in private plans, with many choosing higher-performing plans.6

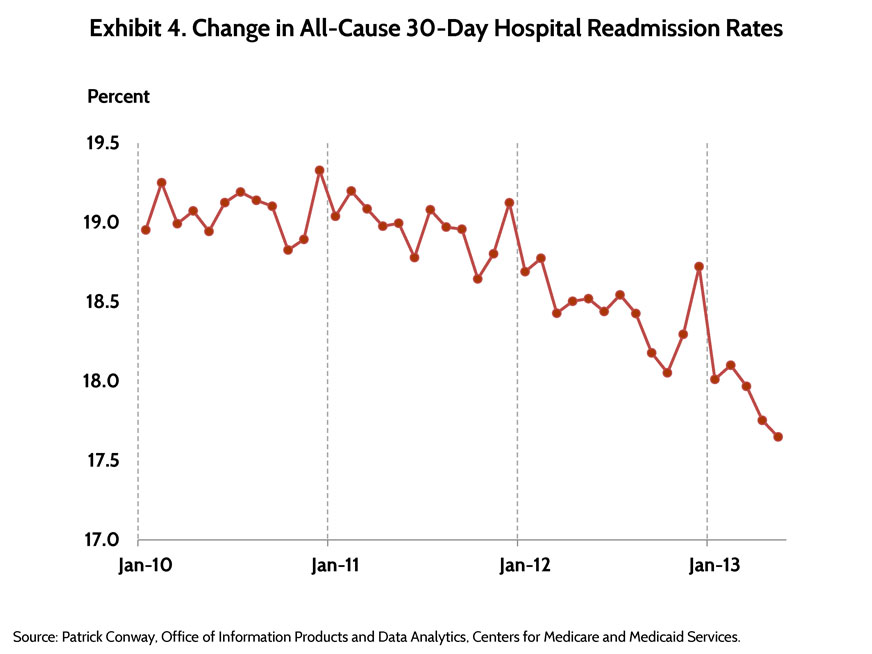

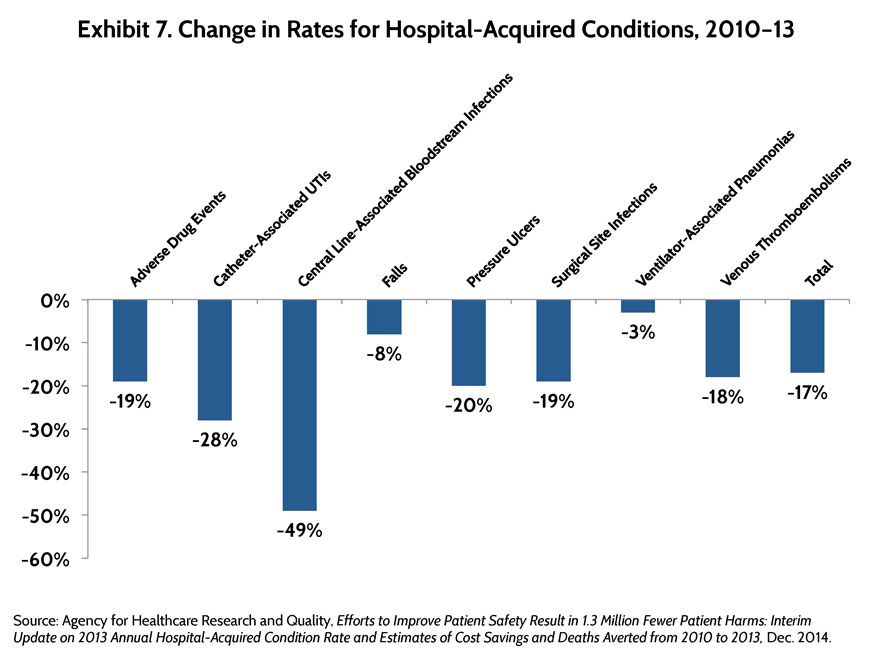

Other ACA provisions target quality problems that lead to inefficiencies and jeopardize patient health. For example, the law imposes financial penalties on hospitals with high rates of hospital-acquired conditions and readmissions, an effort that has likely contributed to the recent reduction in associated adverse medical events (Exhibit 4). The new value-based purchasing program for hospitals, meanwhile, fosters greater accountability for performance by dispensing bonuses and penalties tied to publicly reported quality measures; similar programs for physicians are being implemented in phases, starting in 2015, with a full rollout to all fee-for-service providers in 2017.

The ACA provisions also seek longer-term, systemic change in how health care is organized and delivered. In addition to the accountable care programs and medical home initiatives discussed above, the ACO is also testing a payment approach known as bundled payment, a single reimbursement for all the services required for a given medical condition or procedure. This means that physician, hospital, or postacute services can all be covered under a single payment, which should incentivize the various providers involved in a given patient’s care to work better together. Nearly 7,000 postacute care providers, hospitals, and physician organizations have signed up to participate in bundled-payment demonstrations, which represent a further step away from payment for individual services and toward shared accountability for quality and costs.

Most of the new payment models are still in their early phases, and evidence of their impact is far from definitive. Many initiatives have adopted an incremental approach to financial accountability, often starting with pay-for-reporting or bonus-only options (Exhibit 5). The gradual approach recognizes that the type of structural change required to be successful under risk-based payment systems takes time, a concern repeatedly voiced by providers.

The pace of change is about to pick up, however. Earlier this year, the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced a goal to have at least 90 percent of traditional Medicare payments linked to some form of ACO, medical home, bundled payment, or other value-related approach by 2018.7 A private-sector consortium has set a similar goal for its member businesses.8 In fact, an important effect of the ACA is how it has opened up new channels of communication between providers and CMS about the design and implementation of new payment and delivery models. The CMMI Innovation Awards program, for example, encourages health care organizations to propose new care delivery and payment initiatives for piloting. And provider involvement in the design of the law’s ACO and bundled-payment provisions enabled CMS to create programs that have attracted large numbers of participants. CMS and providers are now sharing much more data to monitor and gauge program performance. While implementation of these new programs has not been without delays and hiccups, the culture change occurring across the health care sector may soon make greater strides possible.

Resources for Systemwide Improvement

The Affordable Care Act created a number of new resources to establish a foundation for accelerated public- and private-sector innovation in health care delivery. These institutes and agencies, described briefly below, appear to be contributing to growing momentum in the U.S. to reconfigure how care is delivered and paid for. (See Appendix A. Selected Health Care Payment and Delivery System Reform Provisions of the Affordable Care Act.)

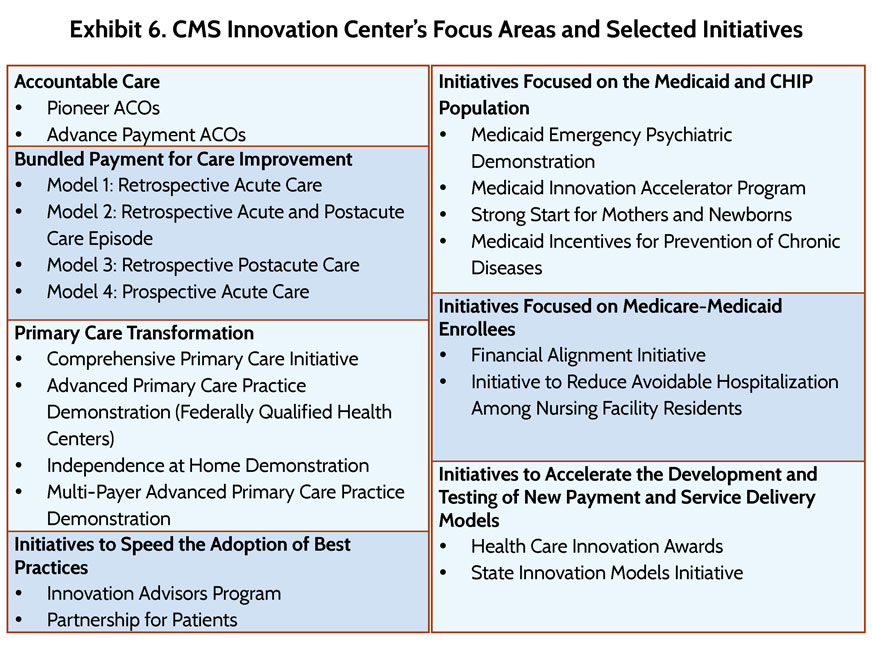

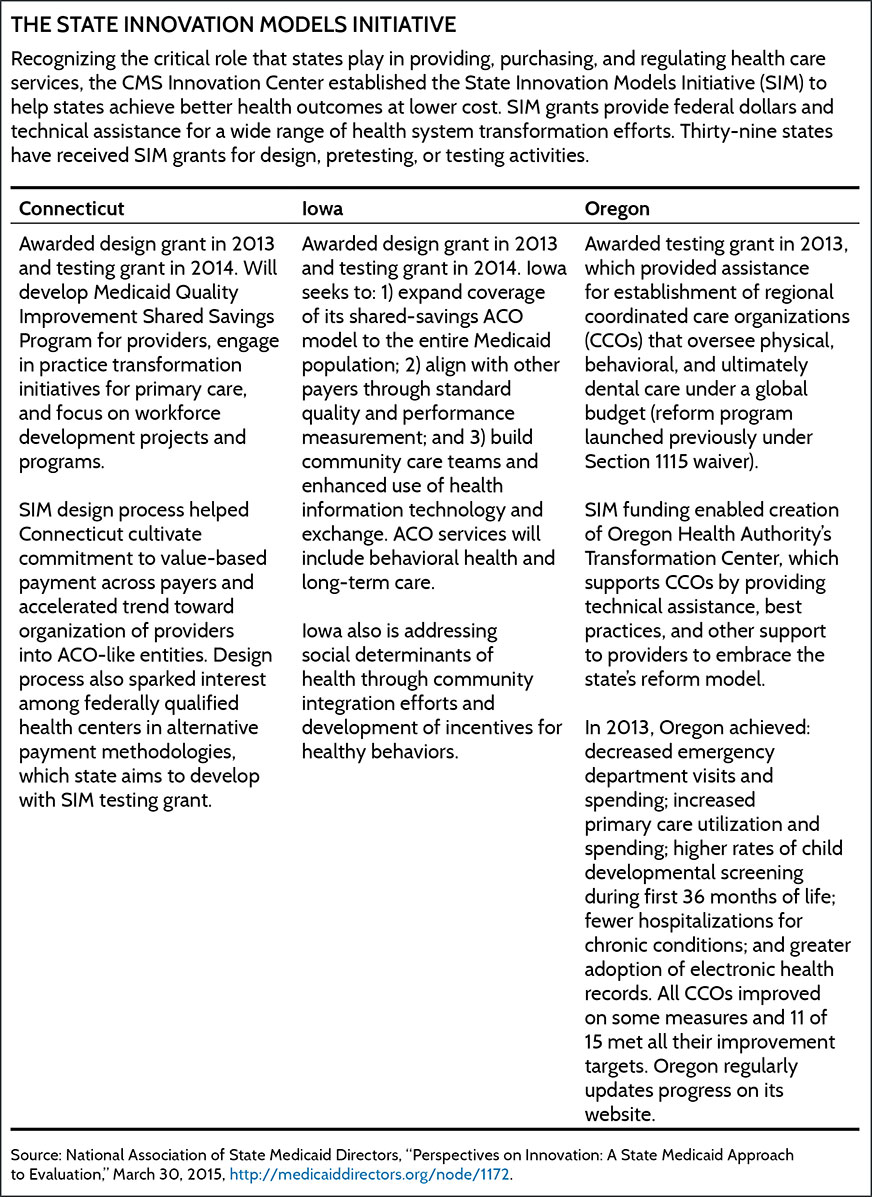

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. As mentioned earlier, CMMI, also known as the CMS Innovation Center, was established to identify, test, and spread new payment and service delivery models to reduce expenditures while maintaining or improving quality of care for beneficiaries of Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services has been granted authority to expand innovations if evidence shows actual cost reductions or improvements in outcomes. When the ACA was enacted, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the Innovation Center, with its $10 billion of direct funding over 10 years, would save $1.3 billion between 2010 and 2019. Since 2010, the center has launched an array of initiatives that together reach more than 2.5 million patients and 60,000 clinicians across the 50 states (Exhibit 6).9 (See sidebar on next page.)

Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Supported through appropriations from general fund revenues and fees assessed on Medicare, private health insurance, and self-insured plans, PCORI funds research on clinical treatments and their outcomes with respect to quality of life, daily functioning, and long-term survival.10 It also is charged with improving the quality, relevance, and translation of the evidence itself, helping to ensure that research results are useful to frontline clinicians. As of April 2015, PCORI has awarded 399 research projects in 39 states, totaling nearly $855 million across five priority areas.11 While preliminary feedback shows that the institute has engaged patients and other stakeholders in developing research questions and reviewing proposals, there are as yet no results available to document the impact of funded projects on patients or providers.

Medicare–Medicaid Coordination Office. The Duals Office, as it is commonly referred to, was created by the ACA to increase coordination between Medicare and Medicaid, which together serve the more than 10.7 million low-income individuals with disabilities who are jointly enrolled in both programs.12 This population generally has more extensive health care needs than other beneficiaries and accounts for a disproportionate share of health spending in both programs. The Duals Office has launched demonstrations to integrate care for these individuals in 18 states through two initiatives: one to reduce avoidable hospitalizations among nursing home residents, and another to test new models to better align the financing of Medicare- and Medicaid-covered services. As of July 2014, CMS had finalized memoranda of understanding with 12 states to implement 13 demonstrations to change the financing arrangements among CMS, the states, and providers serving this population. Although states have submitted plans to evaluate their respective demonstrations, data on beneficiaries’ experience with care or on cost and quality effects are not yet available.

National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care. Designed to align health care improvement efforts across federal, state, and local agencies and the private sector, NQS aims to ensure providers and government are working toward the same goal: healthier communities and lower overall health care costs. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, work undertaken in at least one NQS priority area—patient safety—has had a significant impact on hospital-based care: between 2010 and 2013, incidents of harm experienced by hospital patients nationwide decreased 17 percent, and potentially as many as 50,000 deaths were avoided, and 1.3 million fewer patients experienced harm from hospital-acquired medical conditions (Exhibit 7).13 These improvements are estimated to have saved $12 billion in health care costs.

Prevention and Public Health Fund. This fund provides sustained national investment in preventive care and public health. Through 2015, it has awarded more than $5 billion to local community efforts.14 Among other things, the fund supports diabetes prevention, immunization programs, tobacco use prevention, and heart disease and stroke prevention. Community Transformation Grants provide resources to state and local governmental agencies and local organizations to address chronic disease; grantees must reduce rates of obesity, tobacco-related death and disability, heart disease, or stroke by 5 percent within five years. Over $370 million has been awarded—20 percent to rural areas—benefiting nearly 130 million Americans.15

Conclusion

Five years after passage of the Affordable Care Act—and fewer years from the time many delivery system reforms got off the ground—a full measure of the law’s national impact is premature. It is clear, however, that the ACA has spurred activity in both the public and private sectors, contributing to the accelerated pace of state and local innovations across the country. There is widespread agreement that fee-for-service health care should no longer be the norm, and that fundamental shifts are needed to produce affordable, high-quality, value-based care.

The ACA has provided a platform and a commitment to testing new approaches to how health care is delivered and paid for, as well as recognition that there is no single solution. Experimentation and innovation, by definition, involve missteps, particularly in these nascent stages of transformation. Whether the payment and delivery system reforms currently being tested have the desired impact will depend on the nation’s ability to continuously test new approaches, correct course when necessary, and apply lessons learned. Seen in this light, promising and discouraging results alike should be examined critically along the way.

Acknowledgements

The Commonwealth Fund would like to acknowledge the team at KNG Health Consulting, led by Lane Koenig, and the team at L&M Policy Research, led by Julia Doherty, for their invaluable contributions to this research.

Notes

1http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/sharedsavingsprogram/News.html.

2 E. Taylor, S. Dale, D. Peikes et al., Evaluation of the Comprehensive Primary Care Initiative: First Annual Report (Princeton, N.J.: Mathematica Policy Research, Jan 2015).

3 The eight states are: Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

4 N. McCall, S. Haber, M. Van Hasselt et al., Evaluation of the Multi-Payer Advanced Primary Care Practice Demonstration: First Annual Report (Research Triangle Park, N.C.: RTI International, Jan. 2015).

5 B. Biles, G. Casillas, G. Arnold, and S. Guterman, The Impact of Health Reform on the Medicare Advantage Program: Realigning Payment with Performance (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 2012).

6 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Medicare Advantage Enrollment at All-Time High; Premiums Remain Affordable,” press release, Sept. 18, 2014, http://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2014-Press-releases-items/2014-09-18.html.

7 S. M. Burwell, “Setting Value-Based Payment Goals—HHS Efforts to Improve U.S. Health Care,” New England Journal of Medicine, published online Jan. 26, 2015, http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMp1500445.

8http://www.hcttf.org/.

9 Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, Report to Congress (Washington, D.C.: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Dec. 2014), http://innovation.cms.gov/Files/reports/RTC-12-2014.pdf.

10 An estimated $3.5 billion is expected to flow to PCORI from 2013 through 2019. PCORI announcement, Feb. 5, 2015.

11 PCORI fact sheet, http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-About-PCORI.pdf.

12 Medicare–Medicaid Coordination Office, Data Analysis Brief: Medicare–Medicaid Dual Enrollment from 2006 Through 2013 (Washington, D.C.: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Dec. 2014), http://www.cms.gov/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-and-Medicaid-Coordination/Medicare-Medicaid-Coordination-Office/Downloads/DualEnrollment20062013.pdf.

13 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Efforts to Improve Patient Safety Result in 1.3 Million Fewer Patient Harms: Interim Update on 2013 Annual Hospital-Acquired Condition Rate and Estimates of Cost Savings and Deaths Averted from 2010 to 2013 (Rockville, Md.: AHRQ, Dec. 2014).

14 The federal investment in these community-based activities through 2021 is estimated at $10.5 billion. National Association of County and City Health Officials, “Public Health and Prevention Provisions of the Affordable Care Act.”

15 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Prevention and Public Health Fund,” http://www.hhs.gov/open/prevention/index.html.