Nearly 20 years after the landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences study linked traumatic childhood experiences to the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the U.S., some primary care practices have begun screening for exposure to trauma and are adopting the principles of “trauma-informed care” to engage patients whose childhood and adult experiences may be affecting their health and willingness to seek care.

As health systems adopt hot-spotter programs and other initiatives to identify and direct resources to high-need, high-cost patients, some are discovering that the patients who may benefit the most—including those whose physical problems are exacerbated by mental illness, substance abuse, poverty, homelessness, and other social ills—can be the hardest to engage. In clinics, these patients are often labeled as “difficult” or “non-compliant” because they don’t show up for appointments or disregard medical advice. But experts who’ve spent years working with high-need patients say that for many, experiences of trauma—including emotional and physical abuse, rape, combat, and other violence—make it difficult for them to seek medical care or trust their providers.1

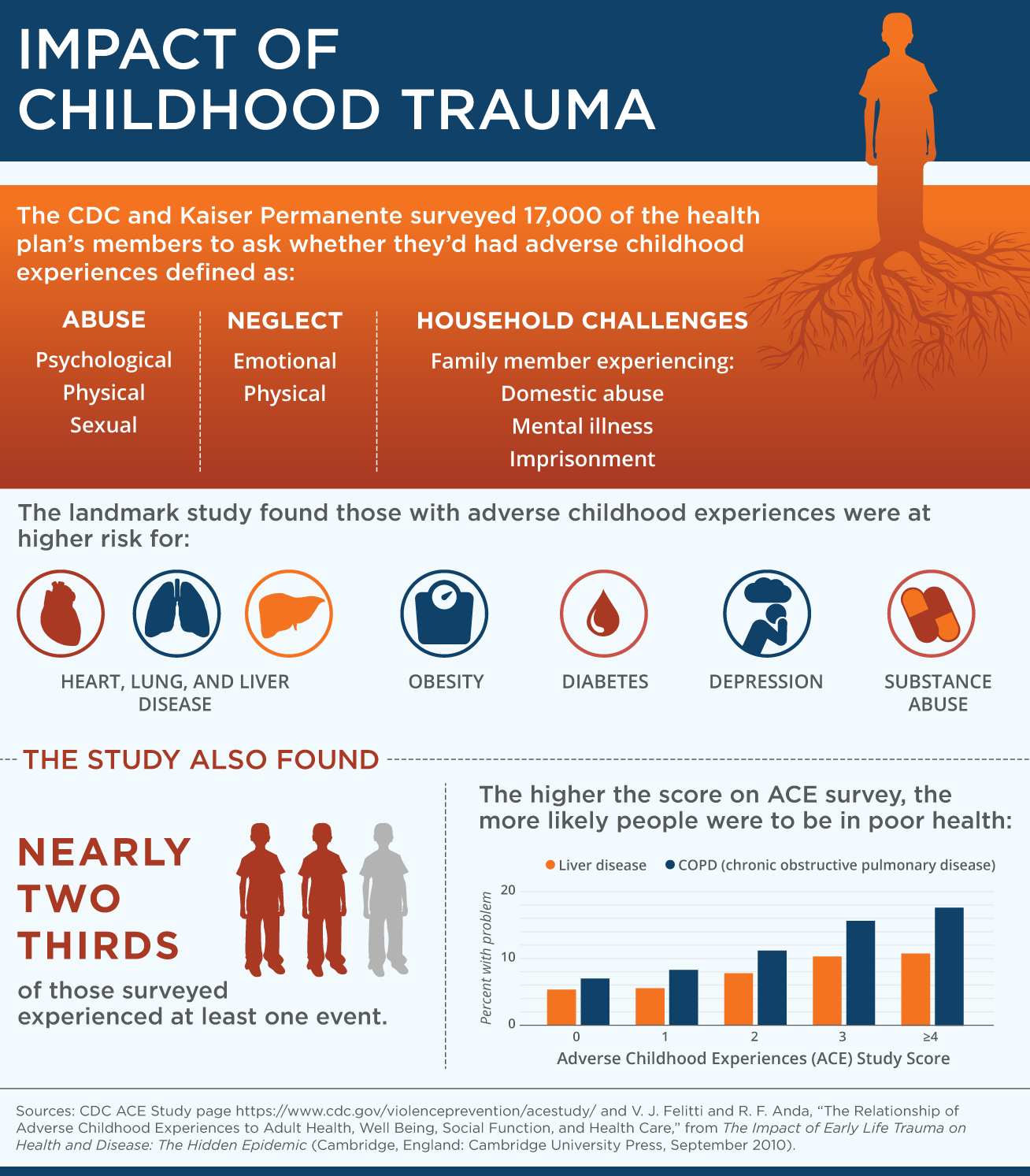

This is a problem given growing evidence of the link between traumatic experiences and poor health. Much of that evidence comes from the landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study, which nearly 20 years ago established the association between traumatic childhood experiences and the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. In that study, researchers from Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found a direct relationship between instances of trauma (defined in the study as sexual, emotional, or physical abuse as well as being raised in neglectful or dangerous households) and rates of chronic obstructive lung disease, lung cancer, heart disease, and liver disease as well as depression, substance abuse, suicide, and risky behaviors.2

Since the ACE study, scientists have begun to identify the mechanisms by which traumatic experiences—among both children and adults—can have long-term impacts on brain development, physiology, and behavior.3 These include changes that affect the way brains perceive pleasure and rewards (implicated in substance abuse), changes to the brain and hormonal systems that react to perceived threats (the “fight-or-flight” response), and even changes to genes that can affect the immune system (making people more vulnerable to some diseases).4

The effects appear to be worse if traumatic experiences occur repeatedly over time. In extreme cases—say prolonged abuse at the hands of a parent or repeated battlefield deployments—some people develop symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, which may include difficulty regulating emotion, impulsivity, and/or persistent anxiety. To cope, they may drink or take drugs, overeat, or adopt other risky and unhealthy behaviors.

"Until people begin to work to address the trauma, they stay stuck in the same cycle,” says Kristine Buffington, M.S.W., a Toledo, Ohio–based clinical social worker who provides training on trauma-informed care to behavioral health providers, child welfare providers, schools, and others."

The ACE study made it clear that traumatic experiences are widespread, including among the largely middle-class, educated, and insured population surveyed. But certain groups of vulnerable patients including the poor may be more likely to experience severe and persistent trauma. The Medicaid health plan CareOregon, for example, has found that more than half of its high utilizers have experienced trauma and a third suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Similarly, more than half of women living with HIV have experienced domestic violence and nearly one-third have PTSD (see Q&A with Edward Machtinger, M.D., director of UCSF’s Women’s HIV Program.)

This issue of Transforming Care focuses on early and evolving efforts to change the way primary care providers screen for and respond to the effects of trauma and describes particular steps practices can take to become what’s been described as “trauma-informed.” Many include elements commonly associated with patient-centered models of care, including encouraging shared decision making, but go a step further by:5

- creating clinical environments that are less likely to trigger traumatized patients—for instance by offering quiet waiting areas and attending to potential triggers during medical exams;

- introducing screening approaches that help patients understand the link between traumatic experiences, unhealthy behavior, and health outcomes; and

- increasing access to treatment in part by streamlining referral pathways to specialty care and/or embedding behavioral health providers in primary care settings.

A New Framework

Many of the early adopters of trauma-informed approaches are health care providers who work with high-risk patients (e.g., veterans, women with HIV, or the homeless) and have struggled to get them to change risky behaviors or manage their conditions. Trauma-informed care offers these providers a new lens through which to view their “difficult” patients. For example, they might come to see certain behaviors—say taking drugs—as traumatized patients’ way of self-medicating, and understand it may take more than just offers of advice or referrals to promote change.

Some of these efforts are supported by The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and led by the Center for Health Care Strategies, which launched a multi-site demonstration to test whether use of trauma-informed practice improves patient engagement, enhances outcomes, and reduces costs. One of its grantees, Bronx, N.Y.–based Montefiore Medical Group, is training all staff at its 22 ambulatory care clinics in approaches to trauma-informed care. The clinics already have behavioral health specialists working side by side with primary care clinicians, helping to serve residents of the nation’s poorest congressional district. Rahil Briggs, Psy.D., director of Montefiore’s pediatric behavioral health services, who is co-leading the effort, notes that while trauma “doesn’t discriminate based on age or sex or socioeconomic status,” many residents of poor neighborhoods are traumatized by community-level violence and the stresses of poverty as well as from direct traumatic experiences.

In addition to offering learning collaboratives on the nature and effects of trauma for clinic leaders, Montefiore will train all staff—from receptionists and schedulers to patient service representatives and providers—in ways to be attuned to how trauma may affect people’s behavior. It then plans to study whether this training influences the diagnosis of trauma and use of behavioral health services, as well as patient satisfaction rates and the incidence of staff burnout (see sidebar on secondary traumatic stress among the health care workforce).

Building Safe Environments

Once primary care staff understand trauma’s pernicious effects, they can work to reduce instances in which a health care visit itself may prove traumatizing. Many practices seek to create more welcoming and soothing physical environments—introducing private waiting areas or in the case of UCSF a therapy dog—since those who’ve experienced trauma may be acutely sensitive to things like chaotic waiting rooms.

Edward Machtinger, M.D., director of UCSF’s Women’s HIV Program says having Pepper, a therapy dog, in the waiting area has had a calming effect on patients who’ve experienced trauma and on staff. From left to right: Cassandra Steptoe, patient; Beth Chiarelli, L.C.S.W., lead clinic social worker; and Vicki Blake, patient.

Practices may also try to anticipate how certain parts of medical exams—undressing and being touched by strangers, for example—may trigger anxiety or fear. Traumatic events are often crimes of power and control,” says Alissa Mallow, D.S.W., director of social work services and interim director of adult behavioral health at Montefiore Medical Group. One way of addressing this it to have providers inform patients of what’s going to happen during each step of a procedure to give them a sense of control and even opt out if something makes them uncomfortable.

While such efforts may sound like the treatment every patient would expect to get, providers may have to “bend over backwards” to build trusting relationships with traumatized patients, says Jennifer Perlman, Psy.D., a psychologist and coordinator of trauma-informed care for the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless. Nearly all of the clinic’s homeless patients have experienced the “trifecta” of trauma, poverty, and addiction, she notes, and they are highly attuned to perceptions of mistreatment. “They often feel like they would rather die before they’ll be further humiliated,” she says.

To make patients feel more comfortable, the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless has used soothing paint colors and offers private spaces to wait. They also make ample use wood and plants. “I often think that’s why some homeless patients who’ve experienced trauma stay outside. Nature is oftentimes more comfortable,” says Jennifer Perlman, Psy.D., the coalition's coordinator of trauma-informed care.

Identifying Trauma

Given the prevalence of traumatic exposure in the U.S. population, advocates advise health care providers to assume that any one of their patients may have experienced trauma, an approach known as universal precaution. And most (but not all) advocates also encourage primary care providers to screen for trauma, using formal tools that ask patients whether they’ve experienced traumatic events without requiring them to elaborate. Others avoid the direct approach by instead seeking to identify trauma through its common consequences—depression, suicidal thoughts, substance abuse, or chronic pain, or even less tangible behaviors such as being quick to anger or zoning out. Noticing such signs is “a good time for a primary care provider to take a step back and wonder what’s happened to this person,” says Glenda Wrenn, M.D., M.S.H.P., a psychiatrist at the Morehouse School of Medicine who works with primary care providers to help patients see the link between unresolved trauma and poor health.

When asking directly about trauma, providers should explain their reasons for doing so, Wrenn says. A physician might tell her obese and potentially diabetic patient with a history of childhood sexual abuse that “the goal is to give you all the resources you need to achieve your optimal health, you have a traumatic background, and we know these experiences can have lasting impacts on your health,” she says. “To do this, you have to feel comfortable talking about the neurobiology of PTSD and how avoidance makes it worse,” she says.

Just broaching the topic can be a challenge for providers. “I think providers are nervous about asking and concerned about their ability to do it well. Fear often gets in the way,” says C. Vaile Wright, Ph.D., director of research and special projects for the American Psychological Association.

Responding Appropriately

Their fear is not misplaced. If patients do reveal a traumatic event, how providers respond makes a difference, Wrenn says: “In those first conversations, you are either going to build on that person’s underlying fear or instill hope.” Providers should acknowledge patients’ courage in being willing to discuss their trauma history and model calm and compassionate responses. “We need to help them start managing and adapting rather than avoiding—teaching them how to calm down their body and pay attention to what’s really happening rather than being caught in a flight-or-fight response,” says Laurie Lockert, L.P.C., an independent consultant who helped set up and run CareOregon’s health resilience program for high-needs patients, described below (see a profile of one health resilience specialist).

Providers should also be ready to help patients find counseling, a support group, or other services, though getting treatment may not be an easy sell. In talking to patients who’ve reported trauma in primary care settings, Wrenn frequently hears things like “I am just messed up because I was raped” or, in many cases, “I brought this on myself.” To engage them, she underscores that the goal of treatment is to improve on their strengths and promote resilience. The initial conversations might focus on areas where patients are functioning well—they’re raising a child, for example, or they’ve gotten themselves to a medical appointment. Emphasizing choice is also important, Perlman says, because lack of control is often one of the defining features of past trauma. “It has to be in your mind at all times that you are trying to empower the person. I always say here are some options.”

Recruiting Allies

Some practices also rely on peer counselors to work with patients who’ve been through traumatic events. In other cases on-site behavioral health staff can join primary care visits to introduce themselves and offer help. CareOregon has a team of 32 social workers, known as health resilience specialists, who are embedded in 24 primary care clinics and serve as intermediaries between primary care providers and patients who are high utilizers of health care services, many of whom suffer from trauma. The health resilience specialists work to improve communication between patients and providers. In one case, a specialist worked with a patient with a history of drug abuse whose doctor assumed was drug seeking when he complained about an injured back. In getting to know the patient, the specialist learned about his trauma history, recognized he felt disrespected by the physician, and helped persuade a new provider that the patient’s solution—a daily dispense program—was worth pursuing. “The specialists are not taking sides,” Lockert says. “They help both patients and providers move forward in a collaborative way.”

The Veterans Health Administration, which screens all patients for PTSD, embeds behavioral health clinicians in primary care practices because many patients are reluctant to seek mental health services. It has also established a free consultation service that allows any clinician treating a U.S. veteran for PTSD to get advice from experienced clinicians about medications, diagnoses, and treatment, and provides educational materials for patients and providers via its website.

Implications

Efforts by primary care providers to become “trauma-informed” will require more than just training, experts say. For the approach to spread, the field likely needs to establish evidence of the impact of such interventions on patient outcomes and utilization rates and to more specifically define trauma-informed care. “I worry about how you determine whether you are a trauma-informed system. Is it what patients think? Is it a self-assessment and if so, what are you using? Without more parameters I think we run the risk of diluting the importance of this,” Briggs says.

The process of changing clinical culture can also take years and it’s a big ask of primary care clinicians, who already have too little time and too many responsibilities. Still, understanding trauma can go a long way toward helping patients whose behaviors may have seemed intractable, advocates say. “I think it’s gaining traction because more people are practicing it and seeing the benefit,” Lockert says. “One of my dreams is to see this being taught in all health care training programs. It is so valuable and can be leveraged to build a trusting relationship so much more quickly.”

Secondary Traumatic Stress Among the Health Care Workforce

| Symptoms of Secondary Traumatic Stress |

Source: National Traumatic Stress Network |

Understanding how trauma can affect the mind and body is critical to ensuring the well being of the health care workforce, experts say. Not only have many health care professionals experienced trauma themselves—in some cases because they come from the same violent, chaotic communities as their patients—they also run the risk of experiencing “secondary traumatic stress” when they learn about or witness disturbing experiences. The risk appears to be greater among individuals who are empathetic by nature or have unresolved personal trauma themselves.6

“Knowing secondary trauma exists is important,” says Karen Johnson, M.S.W., director of trauma-informed services for the National Council of Behavioral Health, an association of community-based mental health and addiction treatment organizations. Many of its symptoms mimic post-traumatic stress disorder, but they can also take the form of compassion fatigue and burnout.

The problem can be acute for staff working with victims of domestic violence as well as with abused children, says Laurie Lockert, L.P.C., an independent consultant who helped set up and run CareOregon’s health resilience program for high-need, high cost patients, many of whom have trauma in their backgrounds. “It’s hard to watch someone being put repeatedly at risk,” she says.

Kristine Buffington, M.S.W., a Toledo, Ohio–based social worker who helps organizations adopt trauma-informed practices, recalls escorting a suicidal woman to a hospital emergency department only to watch her be re-traumatized by security staff, who insisted she be patted down and strip searched. Buffington had tried to explain the woman’s resistance by telling them she’d been raped as a child and as an adult and was staying in a shelter for abused woman, but staff persisted in trying to restrain the woman. “It was one of the worst experiences I’ve ever had,” Buffington says. “It felt so defeating to bring someone to get help and see them actually being hurt more by the experience. I felt I’d let her down.”

Not acknowledging the emotional drain can make it worse, says Jeffrey Ring, former director of behavioral sciences at the Family Medicine Residency Program at White Memorial Medical Center in East Los Angeles and now a principal at HMA. In a videotaped interview designed to help providers understand their reactions, one medical student described having to go to a closet to cry after witnessing a pregnant woman die in the emergency department. “Everyone took care of the clinical encounter and then went back to work. There was no conversation, no processing, no recognition of it—that response happens often in health care,” he says. “We have to train clinicians to be aware of when the work is taking a toll and make sure they take of themselves,” he says.

Organizations implementing trauma-informed care models say supervision is key to recognizing when staff are overwhelmed and may need a break or reassignment. Setting up peer support or buddy programs that allow staff to work through the emotions that arise during difficult cases may also help, as can self-care strategies, including sleep, good nutrition, and exercise.7 Other useful tools include the Secondary Trauma Stress Scale, a 17-item survey designed to measure symptoms associated with indirect exposure to traumatic events.

1 See CDC site, http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/about.html.

2 E. L. Machtinger, Y. P. Cuca, N. Khanna et al., “From Treatment to Healing: The Promise of Trauma-Informed Primary Care,” Women’s Health Issues, May/June 2015 25(3):193–7.

3 Ibid. and R. Oliver, “Traumatic Experiences Weaken Immune-System Gene,” PsychCentral.

4 We do not report on efforts to address trauma among children. For more on this subject, see the TED talk by Nadine Burke Harris, M.D., on the effects of childhood trauma.

5 National Traumatic Stress Network, Secondary Traumatic Stress: A Fact Sheet for Child-Serving Professionals.

6 C. S. Melvin, “Historical Review in Understanding Burnout, Professional Compassion Fatigue, and Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder from a Hospice and Palliative Care Perspective,” Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, Feb. 2015 17(1):66–72.