Having a usual source of care, like a regular primary care doctor, is also considered a strong indicator of health care access. Being insured makes this more likely.15

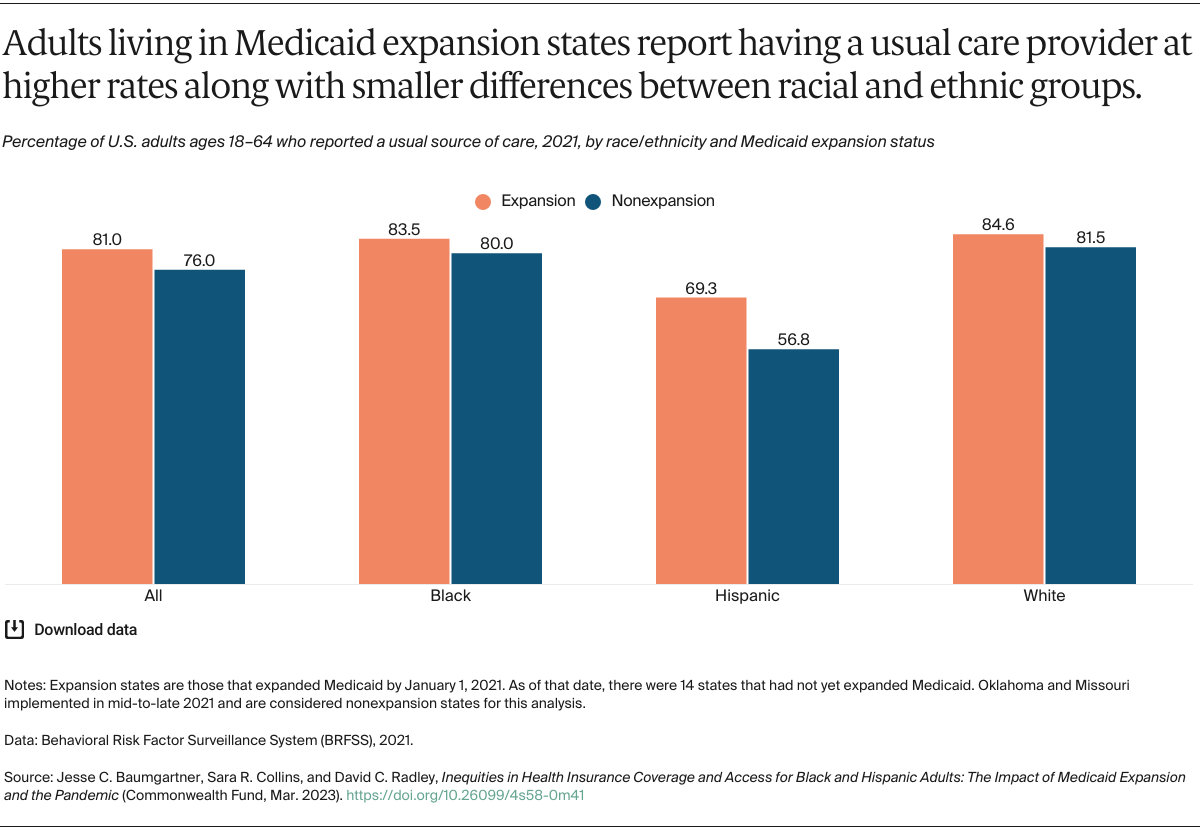

The gap between Black and white adults who reported having a usual health care provider was fewer than 2 percentage points in 2021 (82.0% vs. 83.7%).16 In contrast, just 65.7 percent of Hispanic adults, who are uninsured at higher rates, reported having a usual care provider (Table 5).

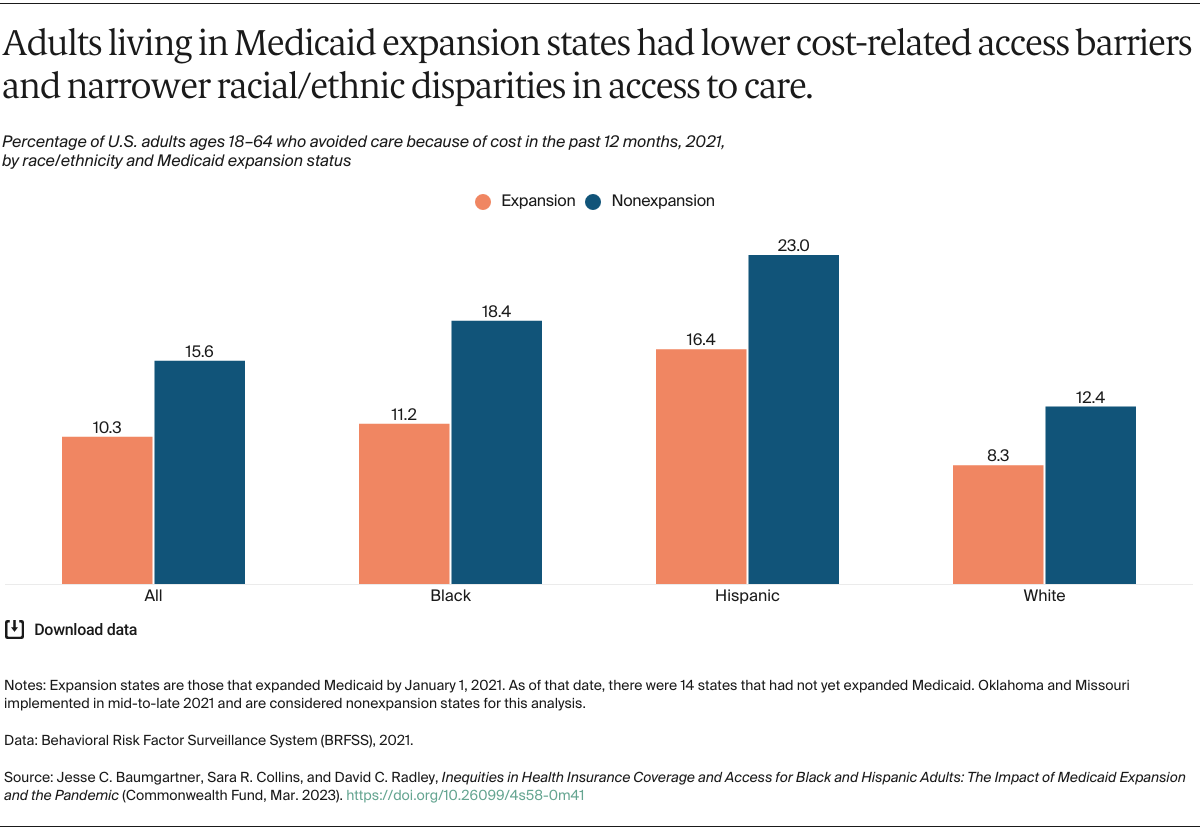

Across each of these three groups, larger shares of adults living in Medicaid expansion states compared to nonexpansion states reported having a usual source of care (Table 5).

Policy Implications

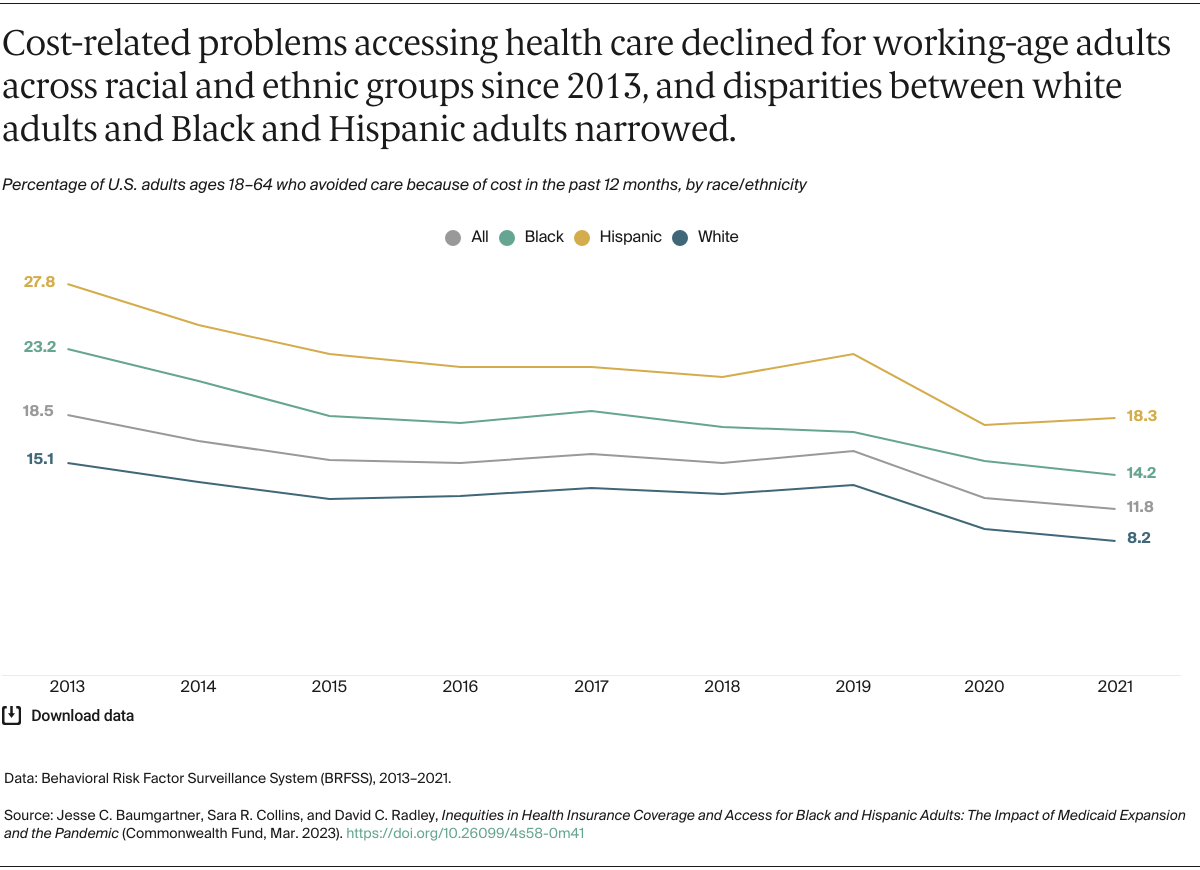

The Affordable Care Act has been a powerful force for racial equity in health and health care over the past decade. The expansion in access to affordable coverage has served as the backbone for this progress, helping to remove financial barriers and increase access to primary care clinics and other providers where people can get the care they need to stay healthy.17 This access has become even more critical during the COVID-19 pandemic.

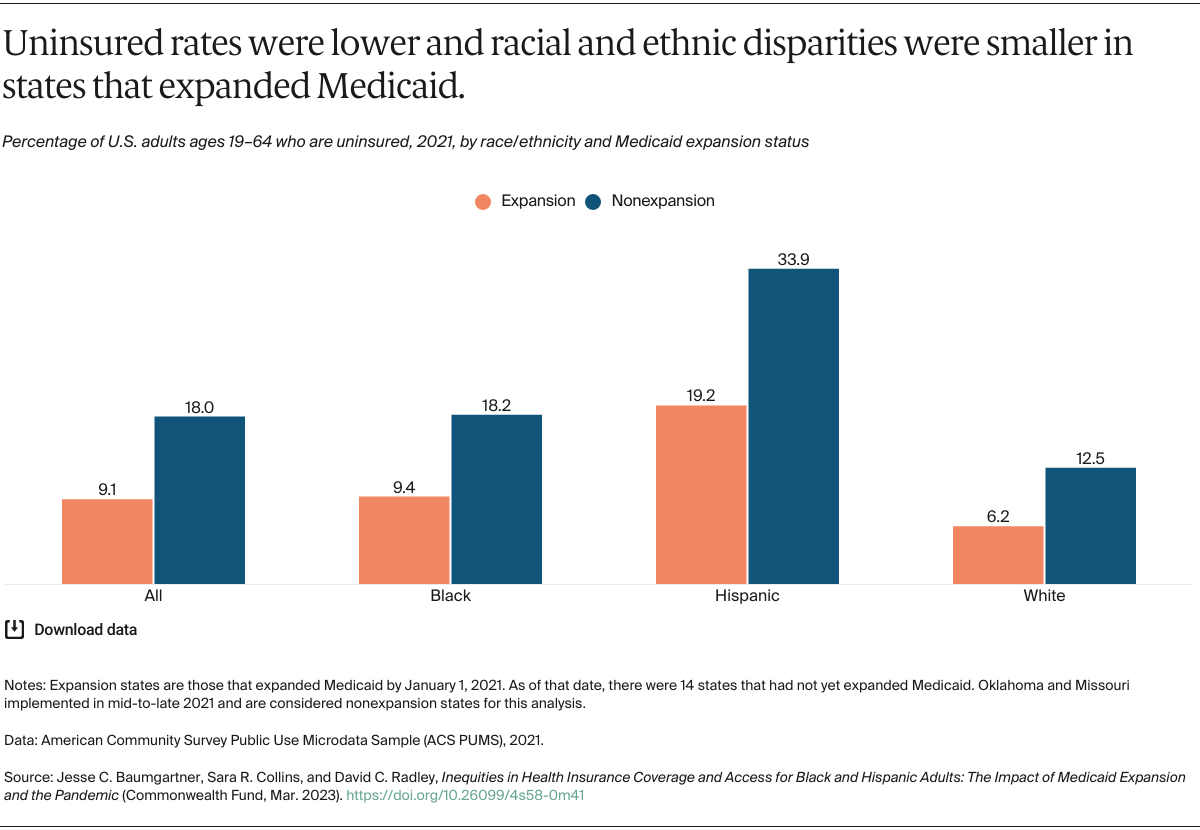

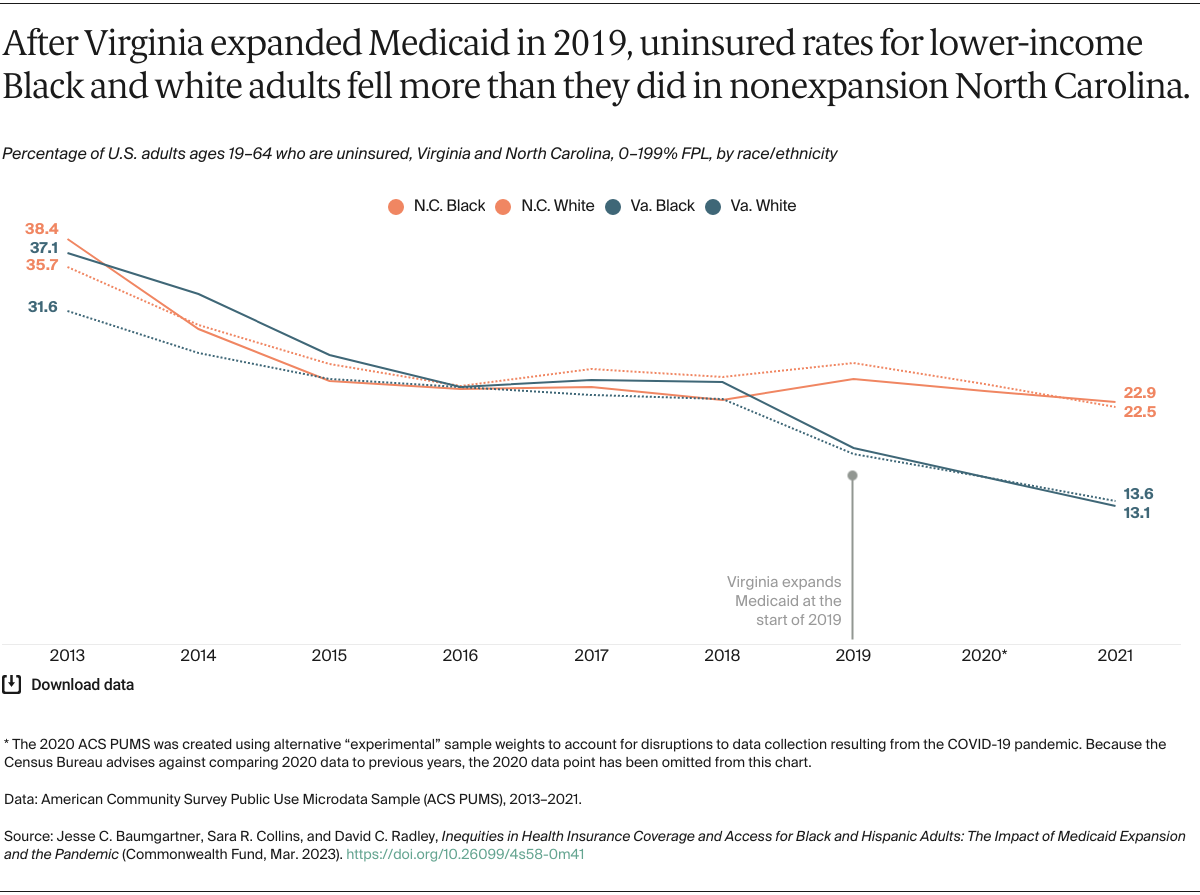

An important part of these improvements is the law’s Medicaid eligibility expansion. As we’ve shown here, Medicaid expansion continues to be associated with greater coverage gains, better access, and narrower racial/ethnic disparities across states. A growing body of research also points to a wide array of improved clinical outcomes, including mortality.18

Seven new states have expanded their Medicaid programs since 2019 (Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Utah, and Virginia). South Dakota recently passed a ballot initiative to expand Medicaid, while several other states, including North Carolina, Wyoming, and Kansas, are considering legislative action or a ballot initiative.19

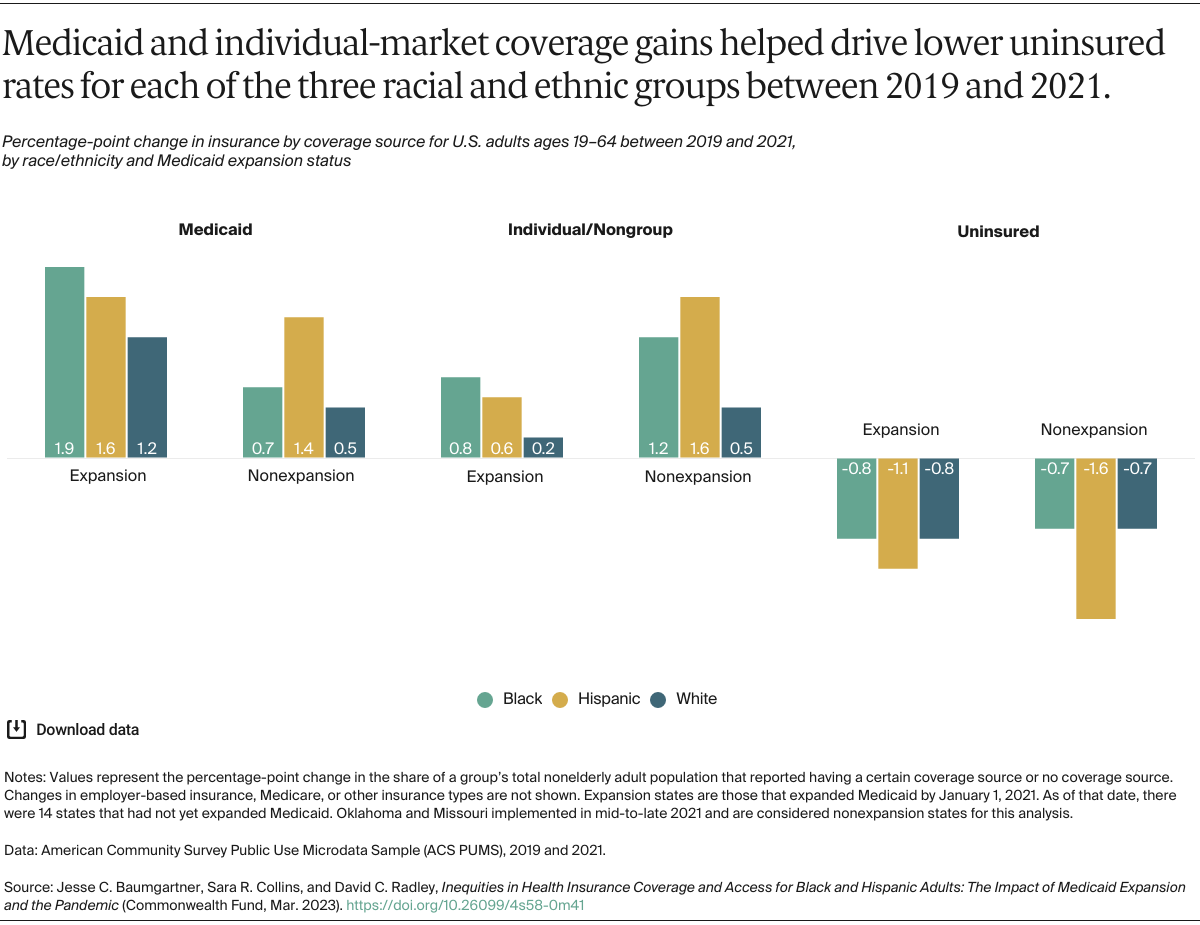

Medicaid, along with marketplace coverage, has helped maintain and improve coverage levels during the pandemic, in large part because of the continuous enrollment requirement of the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which has increased enrollment by more than 21 million people.20 In line with federal data, our analysis points to the critical role of Medicaid in recent coverage gains across both expansion and nonexpansion states, especially for Black and Hispanic adults.21

Along with enhanced premium subsidies in the ACA marketplaces (now extended through 2025) and increased federal funding for marketplace outreach and enrollment activities that lifted enrollment to a record 16 million this year, these policies have helped lower-income Americans, particularly people of color, get affordable health insurance and remain enrolled.22

Despite this progress, key health outcomes such as life expectancy and maternal mortality have worsened during the pandemic, particularly for people of color.23 Achieving full equity in insurance coverage is critical to reversing those trends, particularly since certain COVID-19 treatment and testing benefits are scheduled to sunset when the public health emergency ends in May.24 Protecting progress made and avoiding further coverage gaps will require action on the part of state and federal legislators, including:

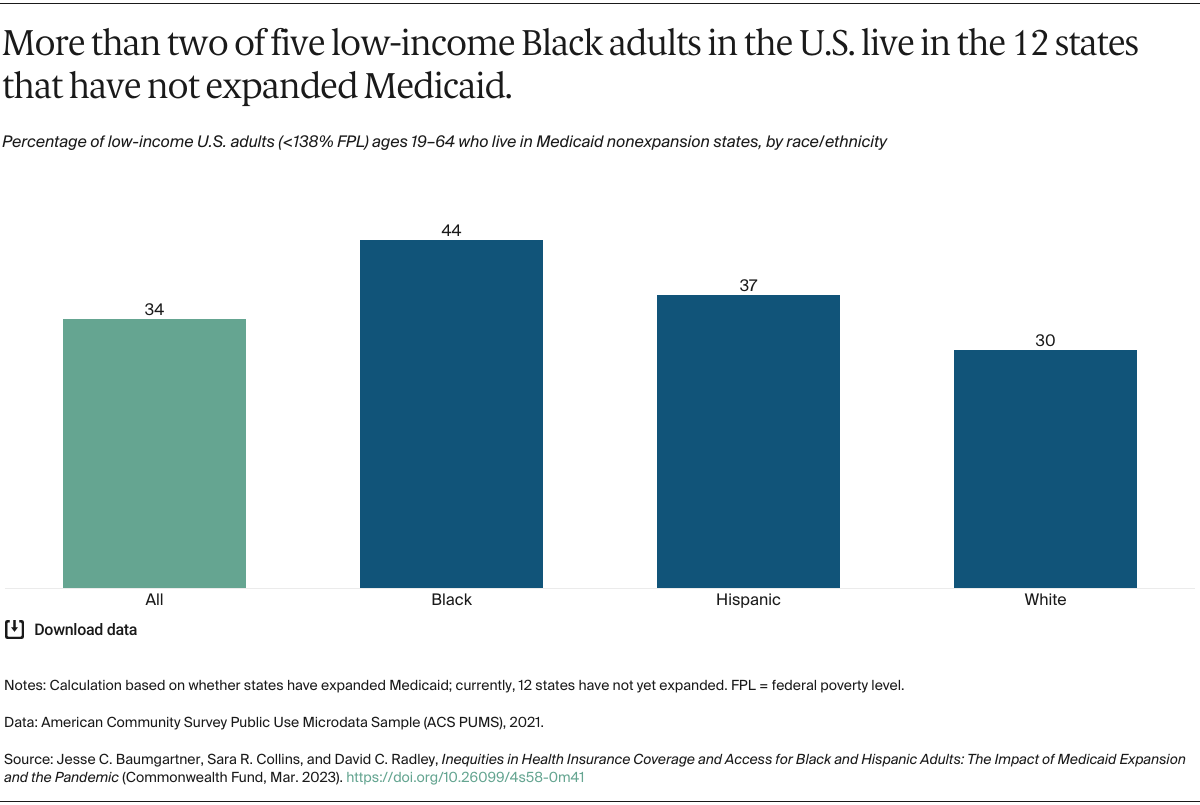

- Filling the Medicaid coverage gap. Despite increased financial incentives during the pandemic, 11 states have yet to expand Medicaid, including some of the most populous and racially/ethnically diverse states. Congress could create a federal fallback option for Medicaid-eligible people in these states.25 The Urban Institute estimates that this reform would cover nearly half a million additional Black residents and shrink the Black–white coverage disparity among nonelderly people to a single percentage point.26

- Minimizing coverage loss during Medicaid eligibility redeterminations. Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately enrolled in Medicaid and thus are especially at risk of losing coverage as states begin to redetermine eligibility on April 1, 2023.27 The Biden administration has emphasized the need for states to do this slowly, allowing them 14 months to complete the process and requiring them to use up-to-date information to ensure against disenrolling people who remain eligible. While the federal omnibus bill phases down the federal matching funds and gives the federal government leverage to stop disenrollment in states that don’t follow federal guidelines, the phase-down is rapid, ending in nine months.28 This gives states an incentive to move quickly.29 As many as 15 million people are projected to be disenrolled, nearly half of whom will likely lose coverage because of administrative churn.30

- Allowing longer continuous eligibility within Medicaid. Disruption in Medicaid coverage because of eligibility changes, administrative errors, and other factors can leave people uninsured and unable to get care. Congress could apply the lessons of the pandemic and give states the option to maintain continuous enrollment eligibility for 12 months without the need to apply for a waiver, just as they have for children in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.31

- Permanently extending enhanced marketplace premium subsidies beyond 2025. The primary reason people give for not enrolling in marketplace plans is the cost of the premium.32 A permanent extension of the enhanced marketplace subsidies is needed to keep people enrolled in plans and encourage new enrollment in the future.

- Creating an autoenrollment mechanism. Research shows that many uninsured people are eligible for Medicaid or subsidized marketplace coverage. Congress could allow people to autoenroll in comprehensive health coverage. The Urban Institute has shown that a comprehensive autoenrollment option has the potential to move the nation to near-universal coverage, and less-comprehensive reforms could still cover millions more.33