Abstract

- Issue: One proposal to reduce high out-of-pocket costs in plans sold through the Affordable Care Act marketplaces is to change the plan category used as the benchmark for determining the tax credit. A switch in the benchmark plan from silver to gold would mean a greater share of enrollees’ health costs would be covered.

- Goal: To analyze how changing the benchmark plan to gold would potentially affect deductibles and out-of-pocket limits and to compare new potential costs to those in employer-sponsored plans.

- Methods: Analysis of the 2022 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation HIX Compare dataset and the 2021 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Insurance Component.

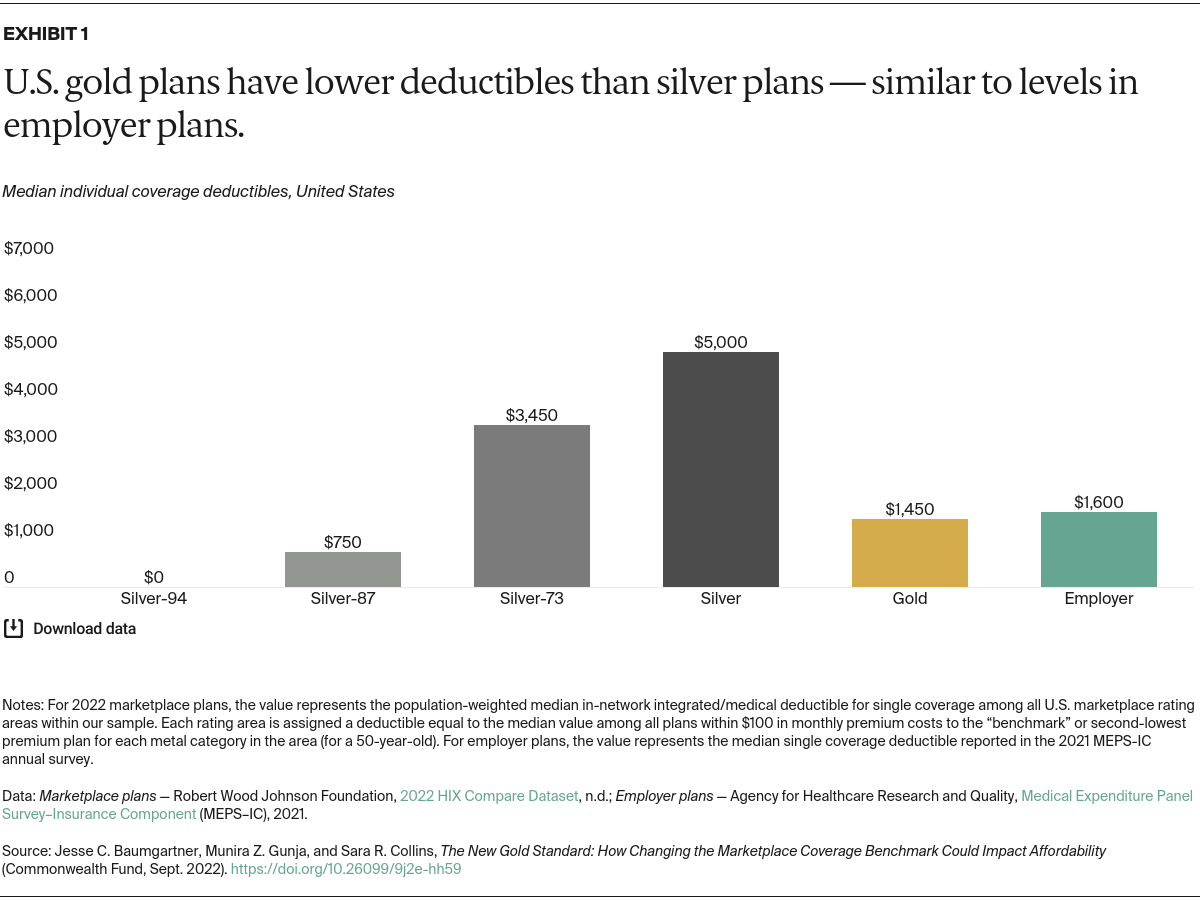

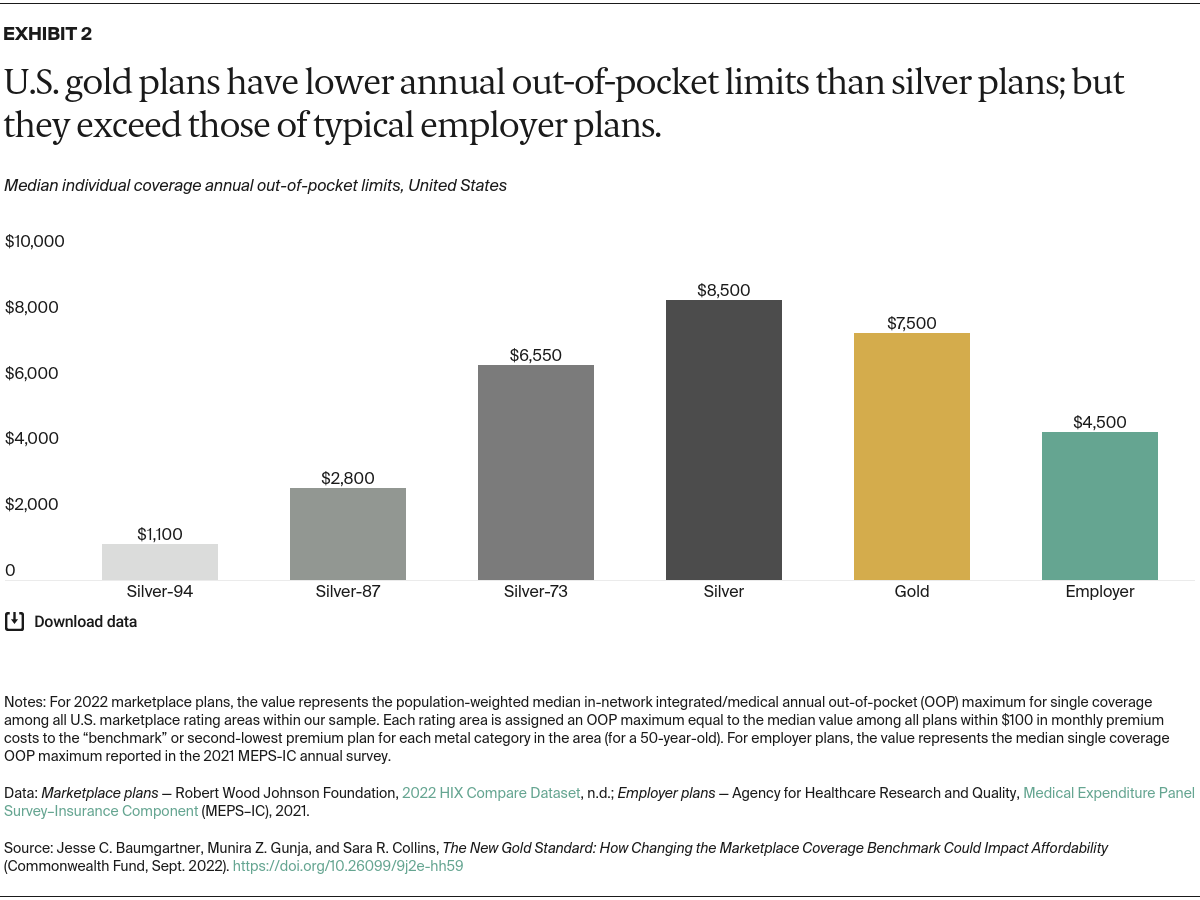

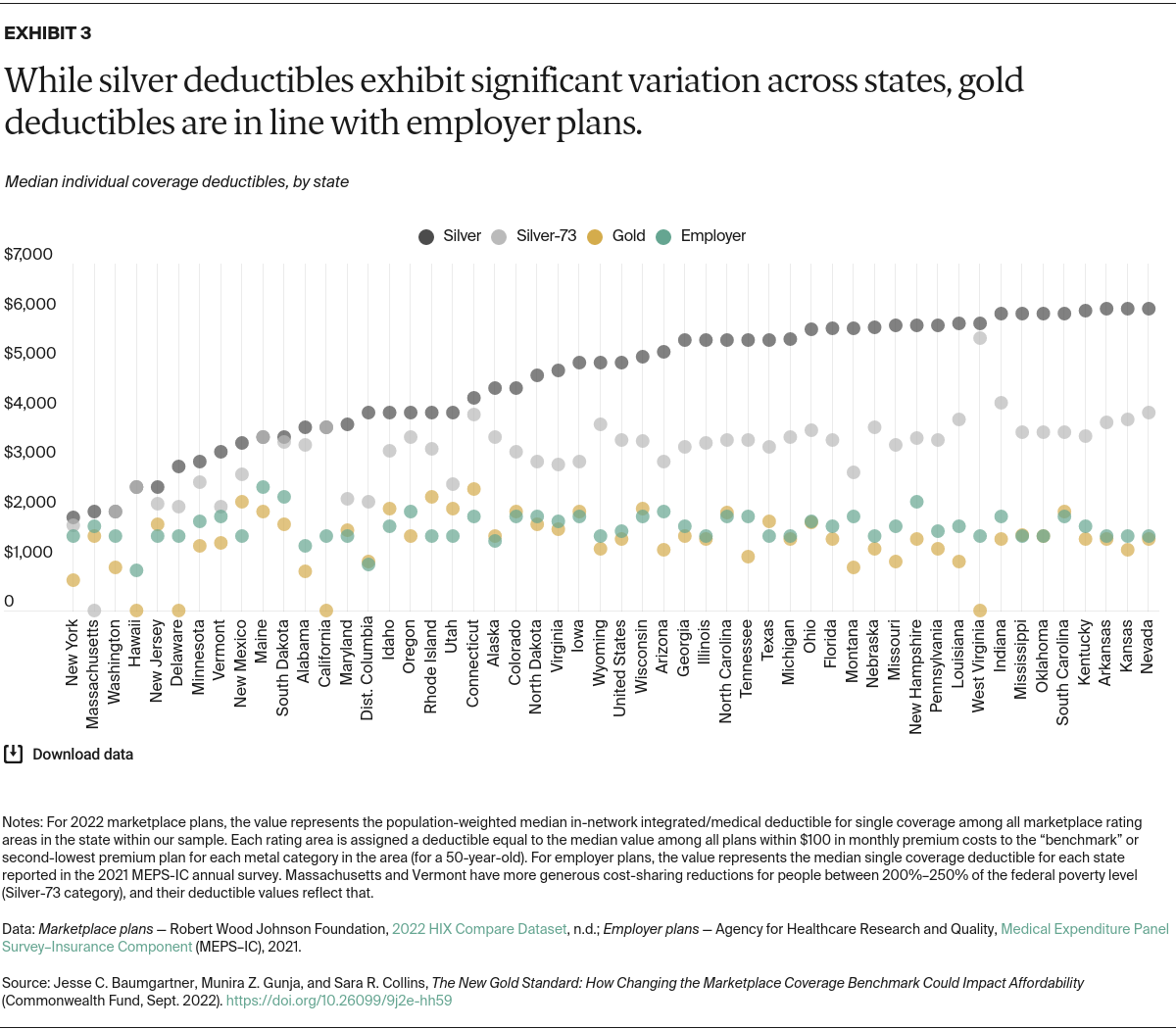

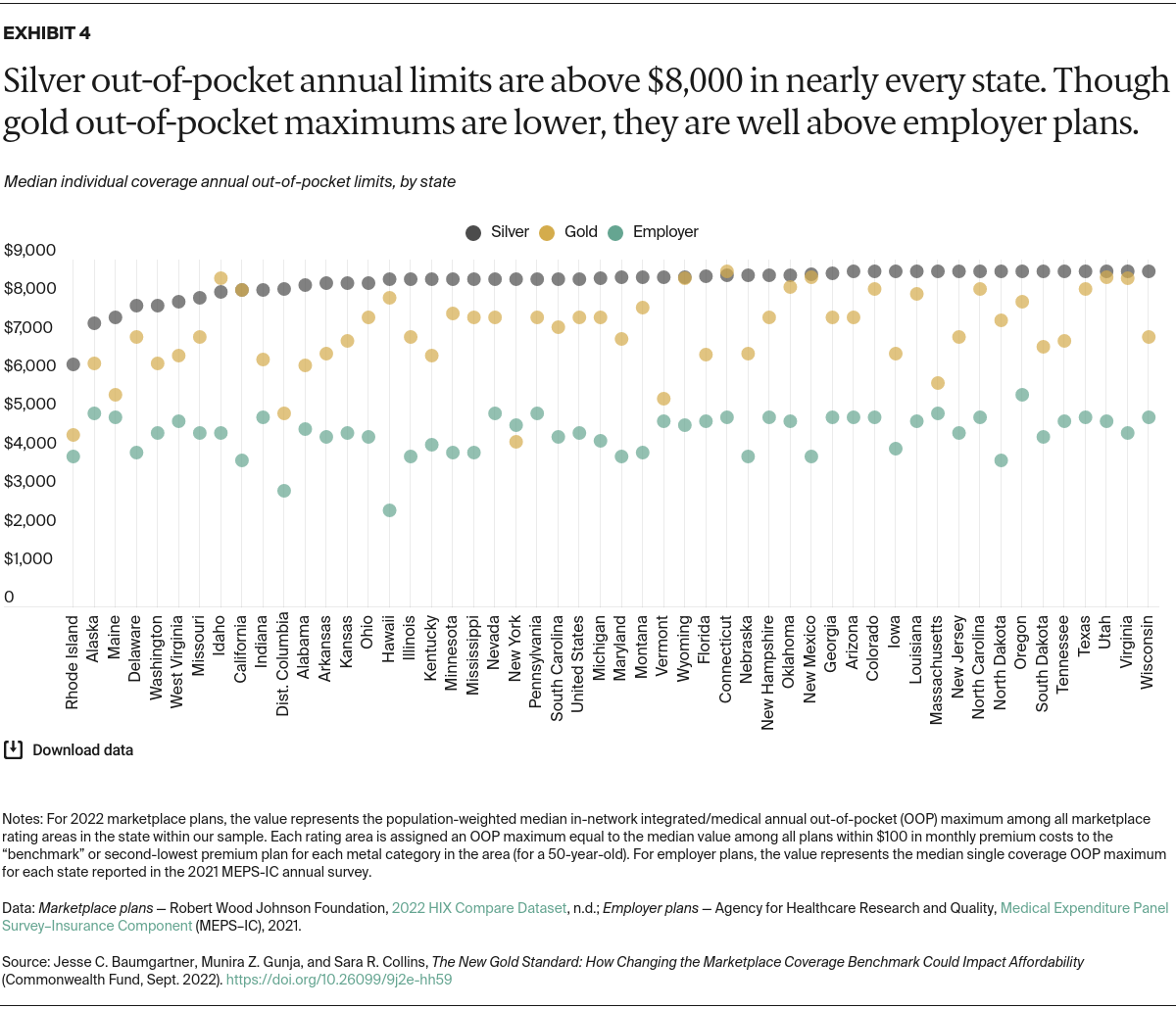

- Key Findings and Conclusions: Changing the benchmark to gold would lower the national median deductible for individual coverage from $5,000 to $1,450, based on 2022 marketplace data. This latter amount is similar to the median deductible in employer plans. The national median out-of-pocket maximum in lower-cost gold plans, $7,500, is lower than silver plans but still much higher than employer plans. Enabling more consumers to afford a gold plan could ease the burden of high deductibles and reduce out-of-pocket spending for lower- and middle-income households in exchange for a moderate increase in federal spending.

Introduction

The affordability of health care is a pressing concern for many people with commercial health insurance plans, both those obtained through employers and through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) temporarily increased subsidies for marketplace plan premiums, making coverage more affordable and helping to drive record plan enrollment during 2021 and 2022.1 The Inflation Reduction Act extended those subsidies through 2025.2

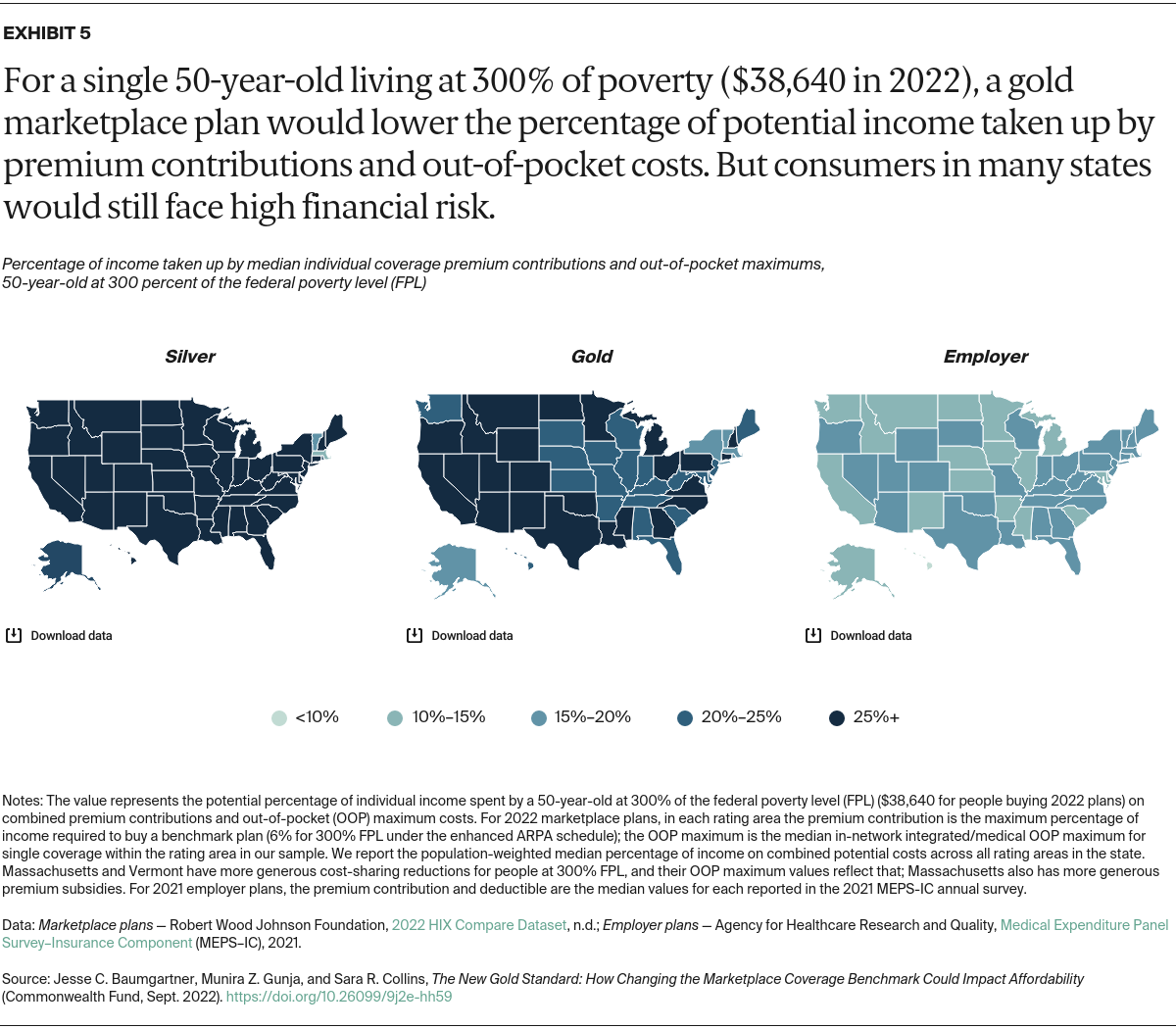

Although premium costs are important, people accessing care also face financial risk from deductibles and other cost-sharing features, like the annual out-of-pocket maximum. Marketplace plans protect people with very low incomes from high out-of-pocket costs through additional subsidies. But people with slightly higher incomes can face high cost sharing within the marketplace’s silver “benchmark” plans, which determine the size of the premium tax credit.3 In many states, the typical single-person deductible can exceed $5,000.4

In recent years, cost sharing in employer-based health plans, long viewed as the top tier of private coverage, also has increased.5 Research shows that people with high deductibles are more likely to skip needed care, delay filling prescriptions, and have problems paying medical bills.6

A bill introduced by Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D–N.H.), S. 499, attempts to address these concerns in the individual market by resetting the marketplace benchmark plan (both single-person and family coverage) from silver to the more comprehensive gold level, among other provisions.7 Funded by the federal government, this policy change would reduce the exposure to out-of-pocket costs that consumers with marketplace plans face by lowering deductibles, copayments, coinsurance, and annual spending limits. Insurers have discretion over which of these levers they choose to adjust in most states.

This analysis explores the cost-sharing effects of turning to a gold-plan benchmark for single-person coverage in the marketplaces and compares this improvement to costs in employer-based coverage.

We use the 2022 HIX Compare dataset curated by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which provides premiums and benefit details of plans sold in the federal and state-based marketplaces, to compare the deductibles and annual out-of-pocket maximum limits of gold and silver plans near the benchmark. We also compare gold and silver plans to single-coverage employer plans using the 2021 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey–Insurance Component (MEPS–IC).

Finally, we examine the potential implications of a policy similar to S. 499 that would provide all marketplace enrollees with incomes above 200 percent of the federal poverty level with access to benchmark plans with the “gold standard” of cost protection.