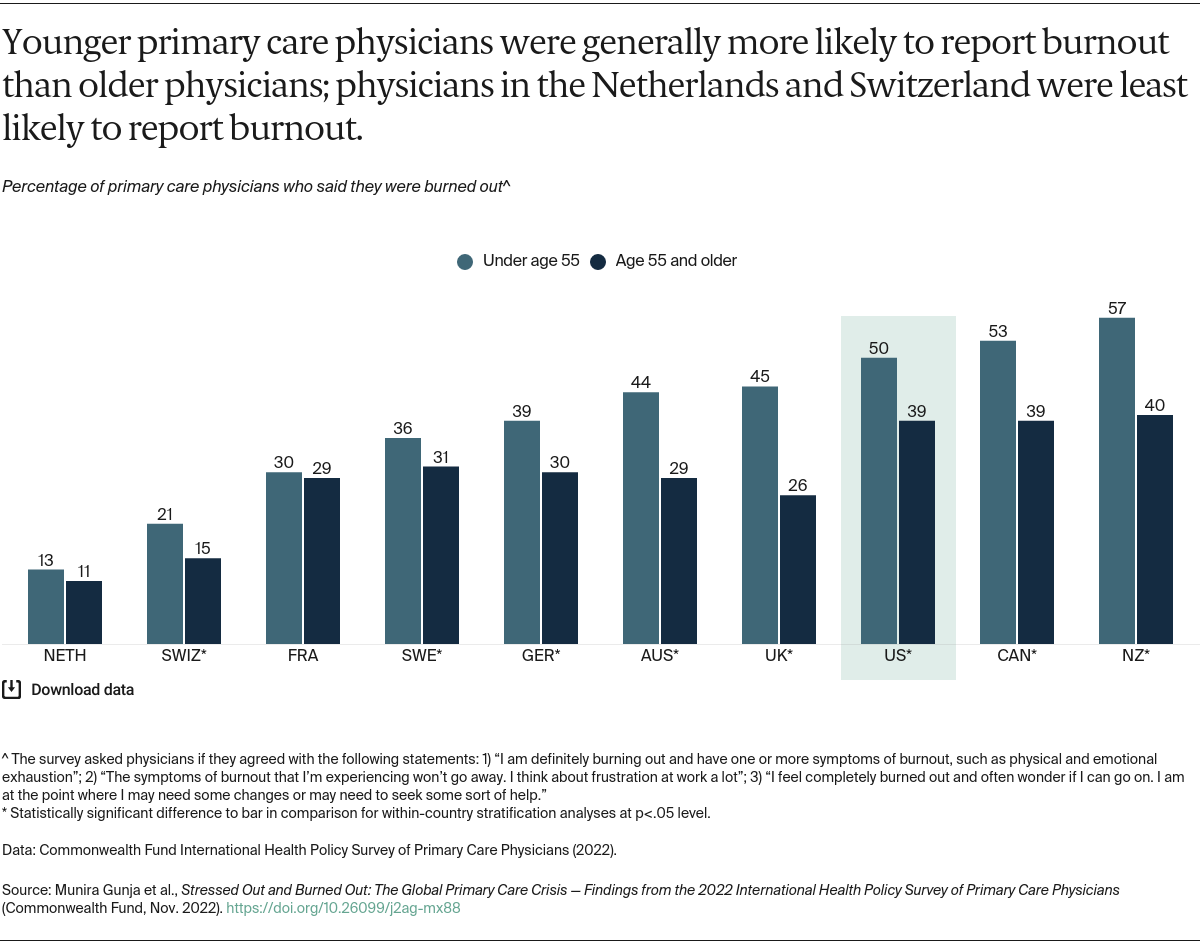

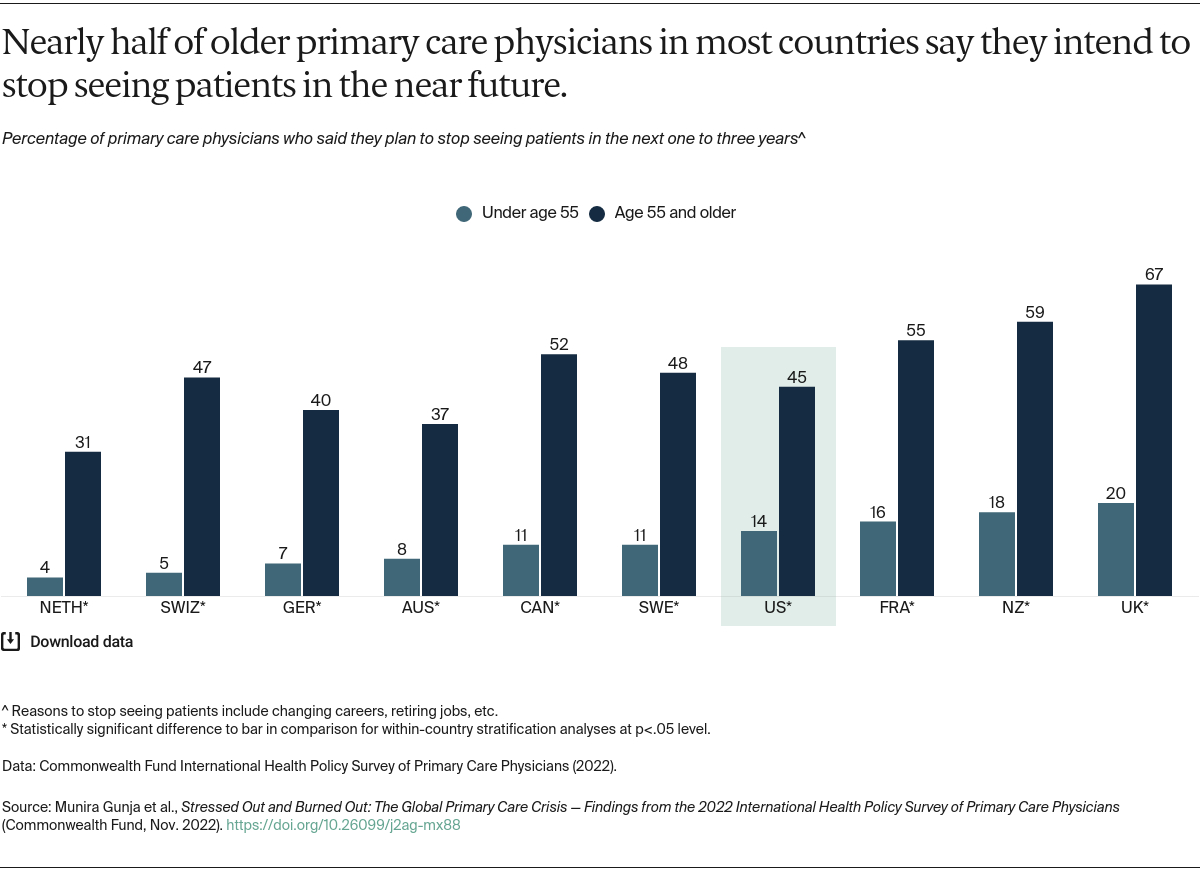

Despite their comparatively lower rates of stress, emotional distress, and burnout, older primary care physicians in all surveyed countries were significantly more likely than their younger peers to report they plan to stop seeing patients within the next three years. These rates varied: about one-third of older physicians in the Netherlands and Australia reported they will stop seeing patients, while the U.K. proportion was two-thirds.

Our findings show that with potentially a third or more of older physicians leaving the workforce in the near future, the majority of primary care physicians in all surveyed countries may soon be younger professionals burdened by stress and burnout (see the table).9

Conclusion

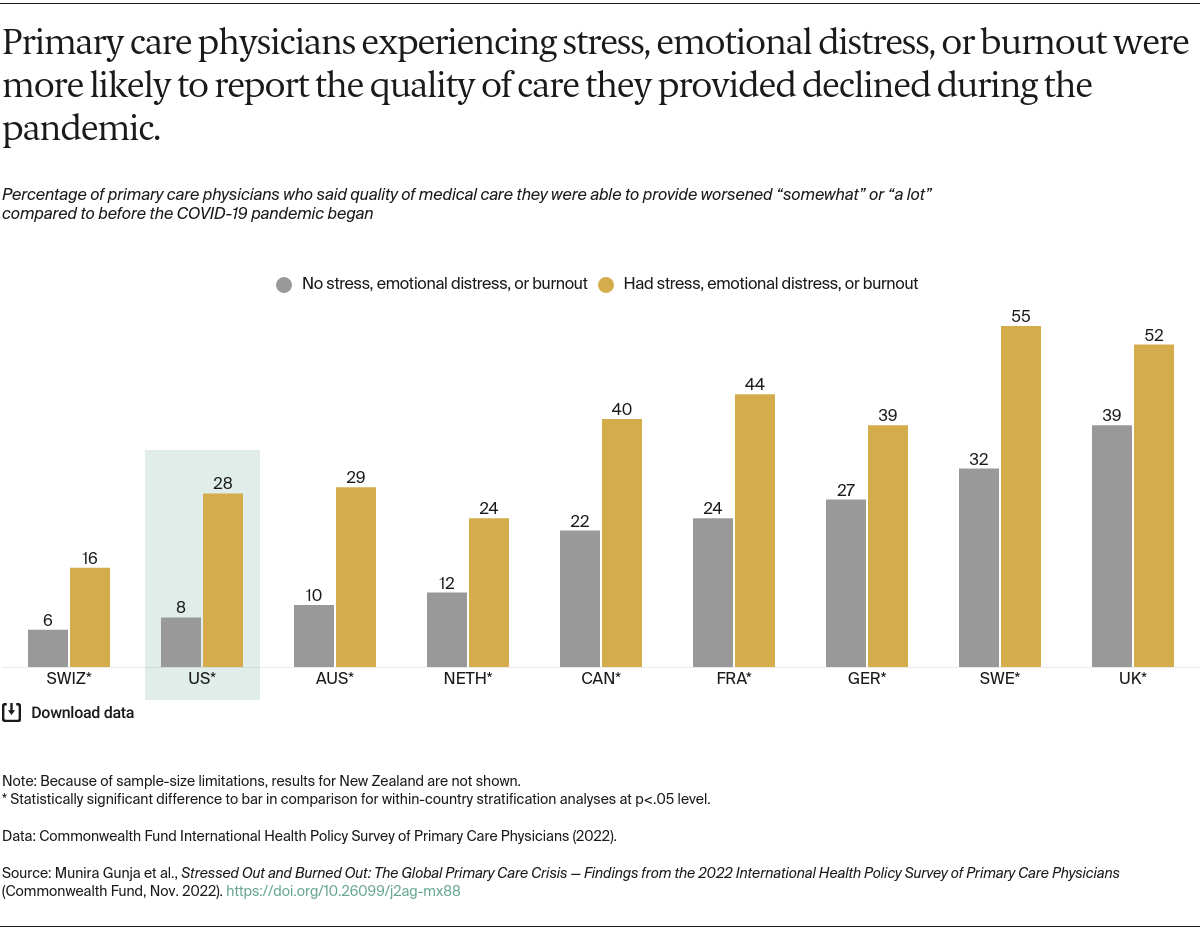

Primary care is the backbone of a high-performing health care system. But the Commonwealth Fund survey results show that health systems across the world are facing a primary care crisis of potentially declining quality of care as well as physically and mentally overburdened physicians.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, it was projected that health systems globally would be facing a shortage of physicians in the coming years.10 Our survey results show that the high rates of physician burnout, stress, and emotional distress during the pandemic may very well accelerate this problem in most of the high-income countries we surveyed, where more than half of older primary care physicians in most countries said they would stop seeing patients within three years. In certain countries, such as New Zealand and the United Kingdom, even many younger physicians say they intend to stop practicing. In the United States, meanwhile, the percentage of medical students choosing to work in primary care continues to decline, with students opting instead for specialty fields.11 It remains to be seen if the pandemic’s impact on the health workforce will have long-term consequences.

What Can We Do?

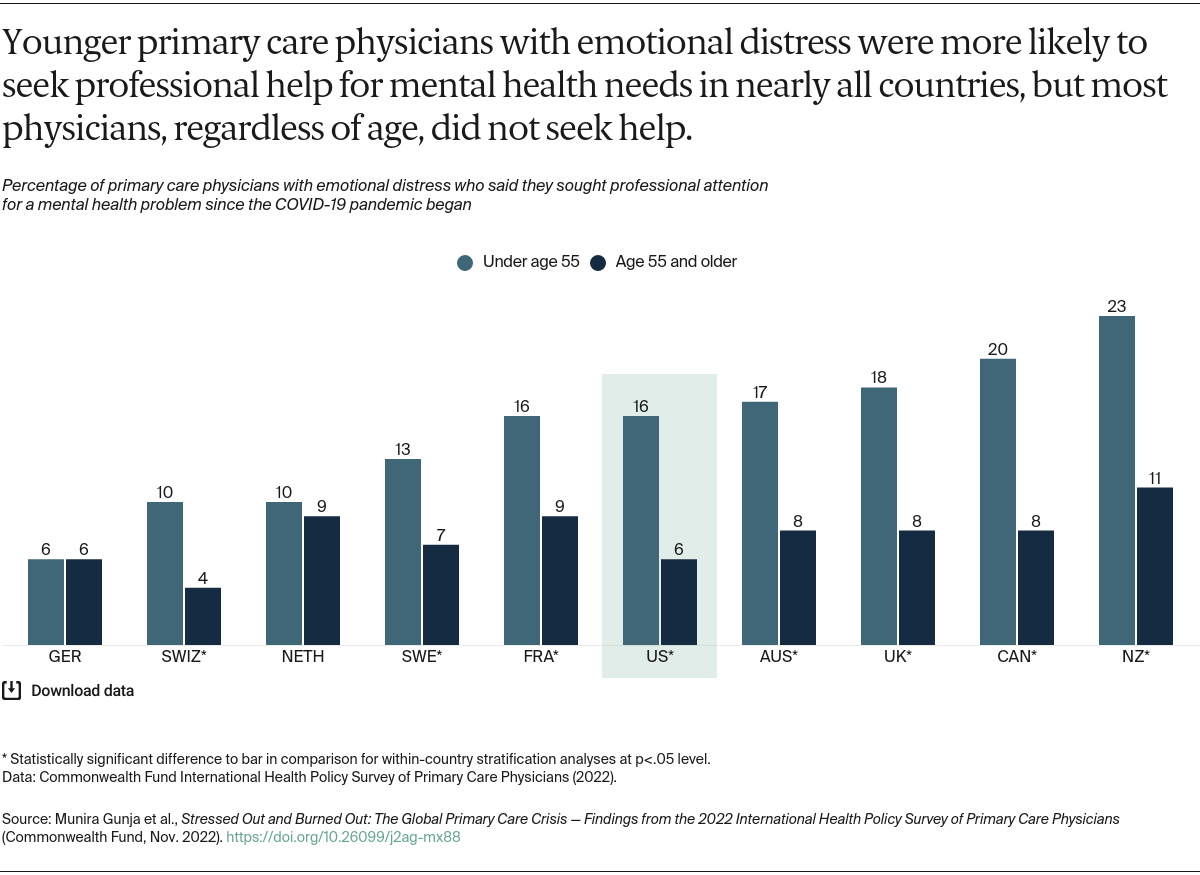

Especially in the wake of COVID-19, policymakers and health system leaders need to take steps to ensure that physicians practice in healthy work environments that are conducive to delivering quality patient care. To start, ensuring that all primary care physicians have access to, and take advantage of, mental health services is critical. The United States has made some initial progress on this front. For example, the National Academy of Medicine’s “national plan” will build on the U.S. Surgeon General’s advisory, as well as related bipartisan policy efforts, to support the mental and behavioral well-being of health workers, including through the recruitment of additional mental health professionals dedicated to serving the health workforce.12

Additional government investment in primary care is likely also part of the solution. In the United States, increasing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement for primary care services could help draw more medical school graduates into the field, as could loan forgiveness programs.13 A number of countries are planning their own investments in primary care. Australia, which has committed $750 million toward improving primary care, recently established its Strengthening Medicare Taskforce to provide recommendations for growing its primary care workforce by the end of the year.14 The United Kingdom pledged in 2019 to expand the number of general practitioners through several broad initiatives, including enhanced recruitment efforts among junior physicians, international recruitment, and deployment of multidisciplinary teams, although this major push has so far achieved limited success.15

In all likelihood, it will require targeted efforts on multiple fronts to increase the supply of primary care physicians, allow physicians to see a more manageable number of patients, and ensure that everyone receives the quality care they expect.16 International comparisons allow the public, policymakers, and health care leaders to see alternative approaches to addressing common problems, including the primary care crisis. The United States has an opportunity to learn what may be working, and not working, from other countries to strengthen primary care. Our analysis demonstrates that now is the time for immediate action.