Abstract

- Issue: Health care costs are highly concentrated among people with multiple chronic conditions, behavioral health problems, and those with physical limitations or disabilities. With a better understanding of these patients’ challenges, health care systems and providers can address patients’ complex social, behavioral, and medical needs more effectively and efficiently.

- Goal: To investigate how the challenges faced by this population affect their experiences with the health care system and examine potential opportunities for improvement.

- Methods: Analysis of the 2016 Commonwealth Fund Survey of High-Need Patients, June–September 2016.

- Key findings and Conclusions: The health care system is currently failing to meet the complex needs of these patients. High-need patients have greater unmet behavioral health and social issues than do other adults and require greater support to help manage their complex medical and nonmedical requirements. Results indicate that with better access to care and good patient–provider communication, high-need patients are less likely to delay essential care and less likely to go to the emergency department for nonurgent care, and thus less likely to accrue avoidable costs. For health systems to improve outcomes and lower costs, they must assess patients’ comprehensive needs, increase access to care, and improve how they communicate with patients.

BACKGROUND

In the United States, patients with clinically complex conditions, cognitive or physical limitations, or behavioral health problems use a disproportionate amount of health care services.1 In any given year, 10 percent of patients account for 65 percent of the nation’s health care expenditures.2 Moreover, many patients with high needs—that is, people with two or more major chronic conditions like diabetes or heart failure—also have unmet social needs that may exacerbate their medical conditions.3

With a better understanding of this patient population, health care providers would be more equipped to develop strategies for addressing behavioral health problems and unmet social needs. These, in turn, could lead to improved medical outcomes and potentially lower health care costs.

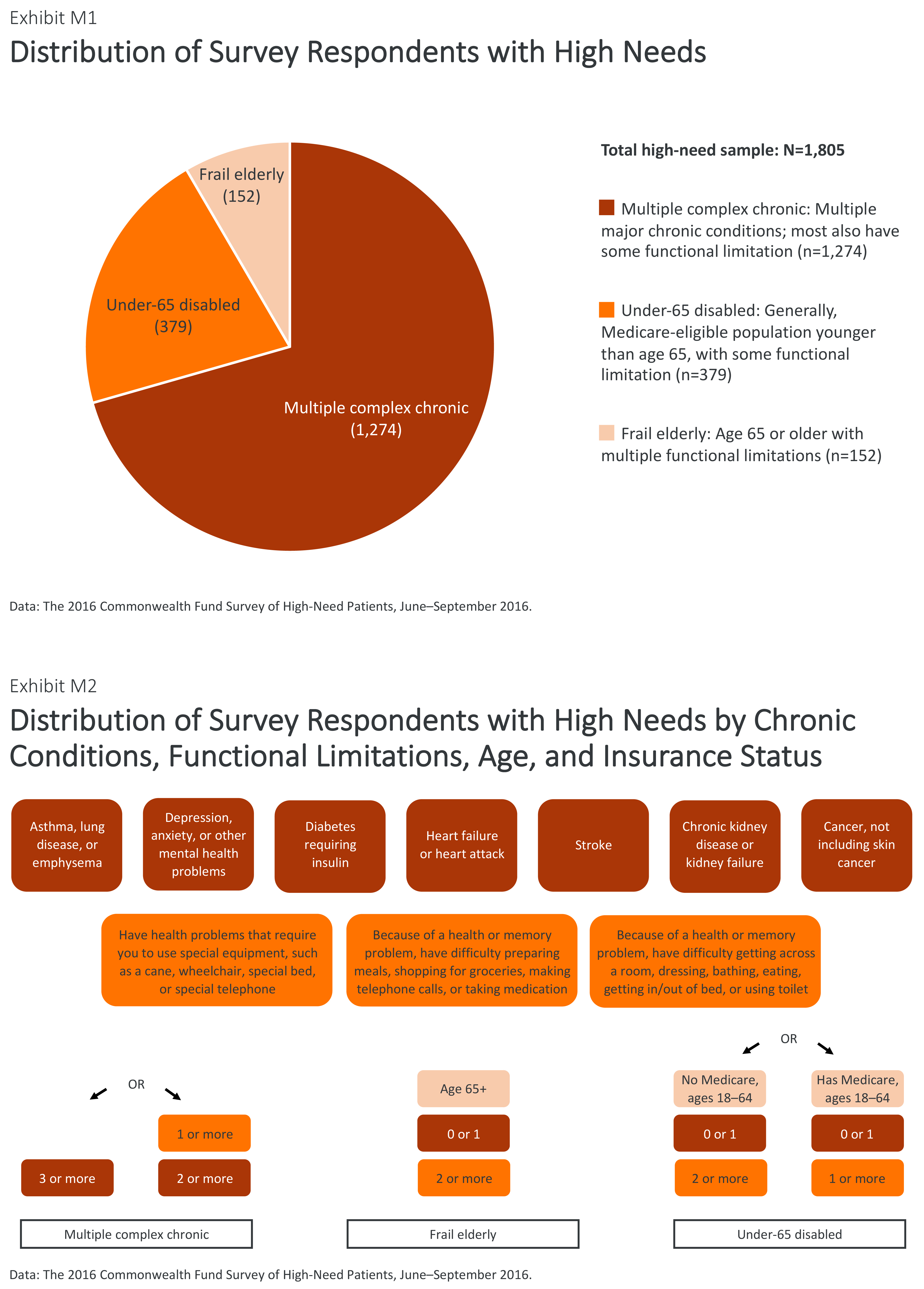

Previous studies by The Commonwealth Fund have examined this population’s demographics and their high use of health care services, but we require additional information about their medical and nonmedical needs, as well as recommendations that could assist health systems to improve outcomes and curb costs.4 The 2016 Commonwealth Fund Survey of High-Need Patients sampled 3,009 U.S. adults, including 1,805 high-need adults and 1,204 other adults without high needs, to investigate how the challenges faced by this patient population affect their experiences with the health care system and where there might be opportunities for improvement. For additional information on the sampling strategy and population breakdown, see How We Conducted This Study.

FINDINGS

This survey confirms prior studies that examined the demographic characteristics of the high-need population.5 Compared with the general population, the high-need population is older, has lower levels of education and income, and includes more women and African Americans (Table 1). High-need patients use more health care services than other adults, as has been reported in previous analyses (Table 2).6 Nearly half (48%) of high-need respondents were hospitalized overnight in the past two years; a similar percentage (47%) went to the emergency department multiple times in the past two years. Approximately one of five (19%) used the emergency department for a condition that could have been treated in a doctor’s office or a clinic.

Many High-Need Patients Report Social Isolation and Other Unmet Social Needs

Adults with high medical needs often have unmet emotional and social needs. The survey results indicate that this group is more likely than the general population to report experiencing emotional distress that was difficult to cope with on their own in the past two years. Nearly four of 10 (37%) high-need respondents reported often feeling socially isolated, including lacking companionship, feeling left out, or feeling lonely or isolated from others, compared with 15 percent of other adults (Exhibit 1). Almost two-thirds (62%) of high-need respondents report stress or worry about material hardships, such as being unable to pay for housing, utilities, or nutritious meals, compared to only one-third of other adults (32%). Furthermore, six of 10 (59%) high-need adults report being somewhat or very concerned about being a burden to family or friends (Table 3).

Nearly Half of High-Need Patients Delay Care and Report Access Problems

High-need patients report problems with access to care (Exhibit 2). More than two-fifths (44%) reported delaying care in the past year because of an access problem such as lack of transportation to the doctor’s office, limited office hours, or an inability to get an appointment quickly enough. Nearly one-quarter (22%) of high-need respondents specifically reported a lack of transportation as a reason for delaying care, compared with only 4 percent of other adults. Three of 10 (29%) high-need respondents reported delaying care specifically as a result of not being able to get an appointment soon enough with their regular provider.

Nearly all high-need respondents (95%) reported having a regular doctor or place of care (Exhibit 3). Yet, only two-thirds of adults (65% of high-need and 68% of other adults) report being able to get an answer the same day when they contact their doctor’s office with a medical question, in line with similar analyses.7 In particular, high-need respondents report difficulty being able to get after-hours medical care on weekends, evenings, or holidays. Only one-third (35%) of high-need respondents reported it was somewhat or very easy to get medical care after-hours without going to the emergency room, compared with more than half (53%) of other adults.

Less Than Half of High-Need Adults Receive Assistance in Managing Conditions

High-need patients are somewhat less likely than others to report receiving care that is accessible, efficient, and high quality. They are also unlikely to have convenient and timely access to key services or supports that can help them manage their conditions outside hospitals or emergency departments.

- Half of high-need respondents reported experiencing emotional distress that they found difficult to cope with alone. Of these, fewer than four of 10 (39%) could get counseling as soon as they wanted (Exhibit 4).

- Of the 53 percent of high-need respondents who reported seeing multiple doctors or using multiple health care services in the past year, less than half (43%) reported having an informed and up-to-date care coordinator (Exhibit 5).

- Of the 57 percent of high-need respondents who have trouble with activities of daily living, fewer than four of 10 (38%) usually or always have someone to help them (Exhibit 6). Among respondents who received help, about three-quarters said it came from family members or relatives (data not shown).

Some high-need respondents are more adversely affected by access issues than others. Among high-need respondents, those who were socially isolated or had low incomes were less likely than respondents without these issues to report having support to manage their conditions, such as easy access to counseling for emotional distress, an informed care coordinator, access to after-hours care, or adequate help for functional limitations (Table 4). Another important factor was their insurance status. High-need adults with employer-sponsored insurance reported a greater likelihood of having these aforementioned resources to help manage their care, while those who are uninsured are less likely to have these resources. Additionally, high-need Medicare and dual Medicare–Medicaid beneficiaries typically had greater access to these resources than the uninsured. While 87 percent of uninsured high-need patients reported having a regular doctor or place of care, less than half reported having an informed care coordinator, adequate help with their functional limitations, patient–centered communication with their regular provider, easy access to emotional counseling, or easy access to after-hours care.

Good Patient–Provider Communication Is Critical for High-Need Population

Patient-centered communication—when patients report that their health care provider listens carefully and involves them in decisions as much as they would like—is critical to high-quality care, especially for high-need patients.8 More high-need patients (60%) than other adults (52%) have doctors or providers who fully engage in patient-centered communication (Exhibit 7). However, high-need adults are less likely to report that their providers specifically involve them in treatment decisions (82% of high-need adults vs. 90% of others) or listen carefully to them (85% of high-need adults vs. 91% of others).

With Good Access and Communication, High-Need Patients Are Less Likely to Delay Care and Visit the Emergency Department

Survey findings suggest tangible strategies to reduce nonurgent emergency department use and to help high-need adults avoid delaying care (Table 2). For high-need patients, having accessible after-hours care, being able to get a same-day answer to a medical question, and having a good relationship with their regular health care provider through patient-centered communication are associated with lower rates of nonurgent emergency department visits for conditions that could have been handled by a regular doctor if one had been available (Exhibit 8). Additionally, having accessible after-hours care is associated with less frequent total emergency department use (both urgent and nonurgent) among high-need patients. While the analysis suggests a relationship between access and communication and a reduction in emergency department visits, there was no similar association with inpatient hospitalizations (Table 5).

For high-need adults, having good communication with their regular provider and good access to care are associated with lower rates of delaying care because of the following reasons: not having transportation, the office not being open when the patient could get there, and not being able to get an appointment soon enough (Exhibit 9). Being able to access care and information in a timely manner are also associated with decreased emotional distress among high-need adults.

IMPLICATIONS

By examining the unique challenges and needs of this patient population, we can identify and develop innovative interventions to meet their needs. In doing this, we should consider the following:

Understand patients’ social and behavioral needs in addition to their medical conditions

The survey findings show the range of social and behavioral health challenges facing these patients in addition to their complex medical conditions. Social isolation and material hardship, for example, have been shown to aggravate medical conditions.9 For health systems, payers, and programs to improve outcomes for high-need adults, providers must consider multiple factors—individuals may have multiple chronic diseases, functional limitations, behavioral health conditions, and material hardships.10 To help people who most need resources, the interventions must be more comprehensive and creative than just a standard set of doctor visits.11 Health care providers should build relationships and collaborate with social service agencies, community-based organizations, and behavioral health providers to deliver better outcomes and avoid high-cost care for this population.

Ensure patients obtain much-needed assistance to manage their health

The results suggest that the health care system is largely failing to meet the complex needs of these patients. Although high-need adults report they are more likely to have—and enjoy good communication with—a regular doctor or place of care, these patients do not receive the services and supports they need. In particular, high-need patients report limited access to known effective supports and services, such as transportation services, emotional counseling, assistance in managing functional limitations, and care coordinators.12 Of patients who have high needs and functional limitations, as well as financial stress, those who had an informed care coordinator or had patient-centered communication with their provider were less likely to use the emergency department for a nonurgent condition (data not shown).

Improve outcomes while potentially lowering costs of care

Health systems are increasingly focused on targeting high utilizers of care as a way to simultaneously improve outcomes and save money. Our analysis suggests two key strategies for improving patient care while potentially curbing costs: increasing patient-centered communication and enabling easier access to appropriate care and information, both of which would support patients in managing their conditions.13 Having timely access to care—by phone, or in person after hours—and good provider–patient communication could potentially reduce nonurgent emergency department visits and help patients avoid delays in needed care.14 Increasing the health care system’s responsiveness to patients in this way could help avoid unnecessary care that drives up the nation’s health care costs.