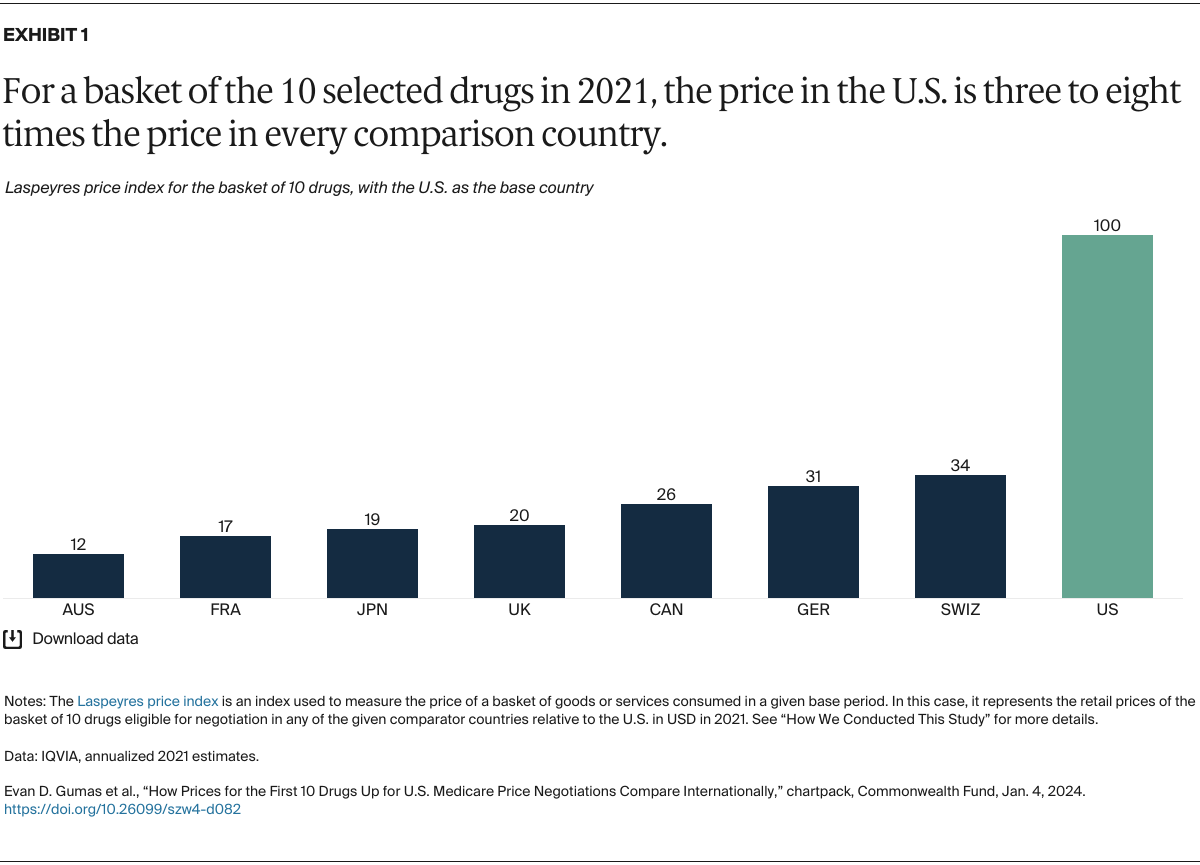

Americans pay more for brand-name prescription medications than do residents of most other countries, with per capita spending on pharmaceuticals nearly three times the average of other member nations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).1 In 2022, high costs forced one of five U.S. adults age 65 and older to skip or delay filling a prescription, miss or reduce doses, or use someone else’s medication.2 More than half of patients resort to cost-coping strategies like coupons or free samples so they can get the medications they need but cannot afford.3 Such stopgap measures can have particularly serious consequences for older people who rely on medications to control chronic health conditions.4

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has empowered the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), for the first time, to negotiate prices on behalf of Medicare for a small group of prescription drugs. Negotiations for the first 10 drugs will begin in February 2024, with price changes taking effect in 2026. This will increase to 15 additional Medicare Part D drugs in 2027, up to 15 Parts B and D drugs in 2028, and up to 20 drugs in subsequent years.5 These price negotiations are projected to save the government $100 billion through 2031, savings that will go in part toward funding an important but costly provision of the IRA that caps Medicare beneficiary spending for Part D drugs at $2,000 per year, starting in 2025.6

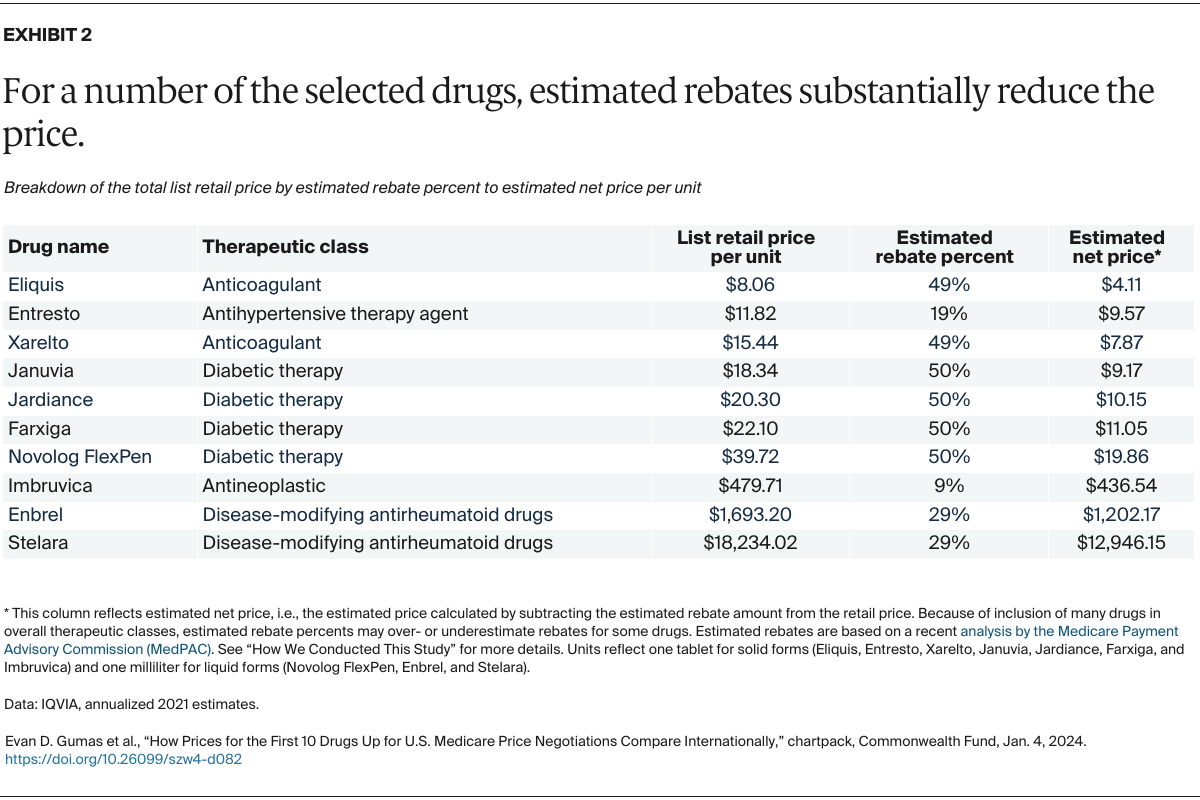

The first 10 drugs to be negotiated by Medicare — used to treat conditions like blood clots, diabetes, and autoimmune disorders — were selected because they account for a significant portion of Medicare Part D spending.7 They meet key criteria set by the IRA for negotiable drugs: 1) no generic versions available, and 2) they are either small-molecule drugs that have been on the market for at least seven years or biologics that have been on the market for at least 11 years.

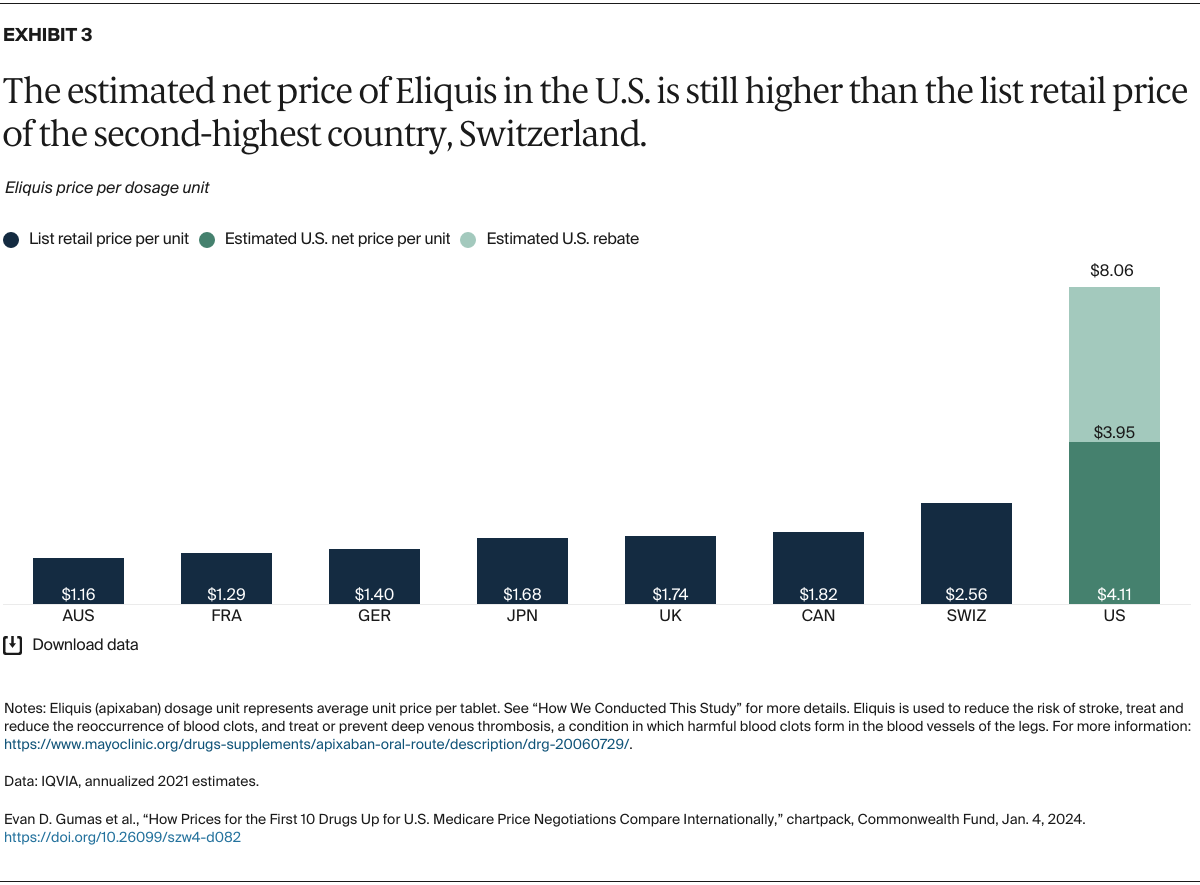

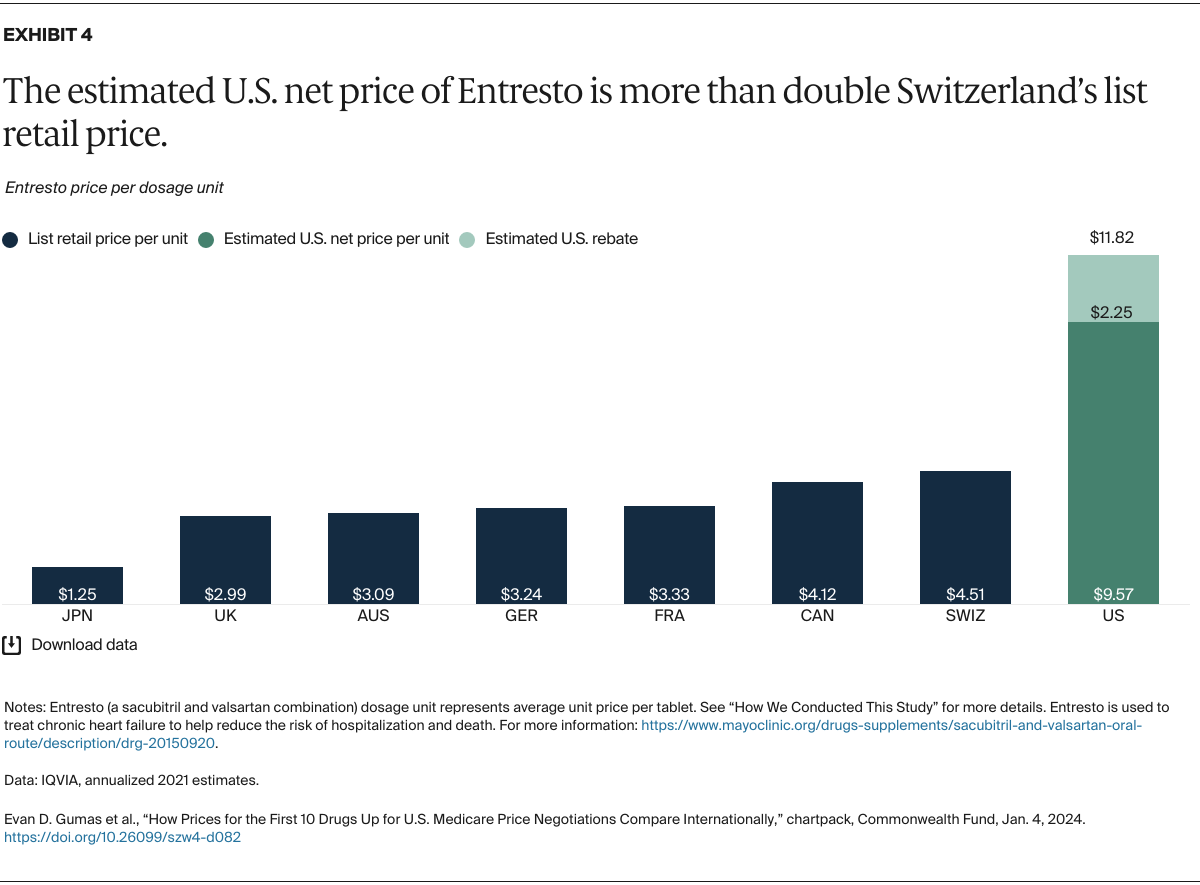

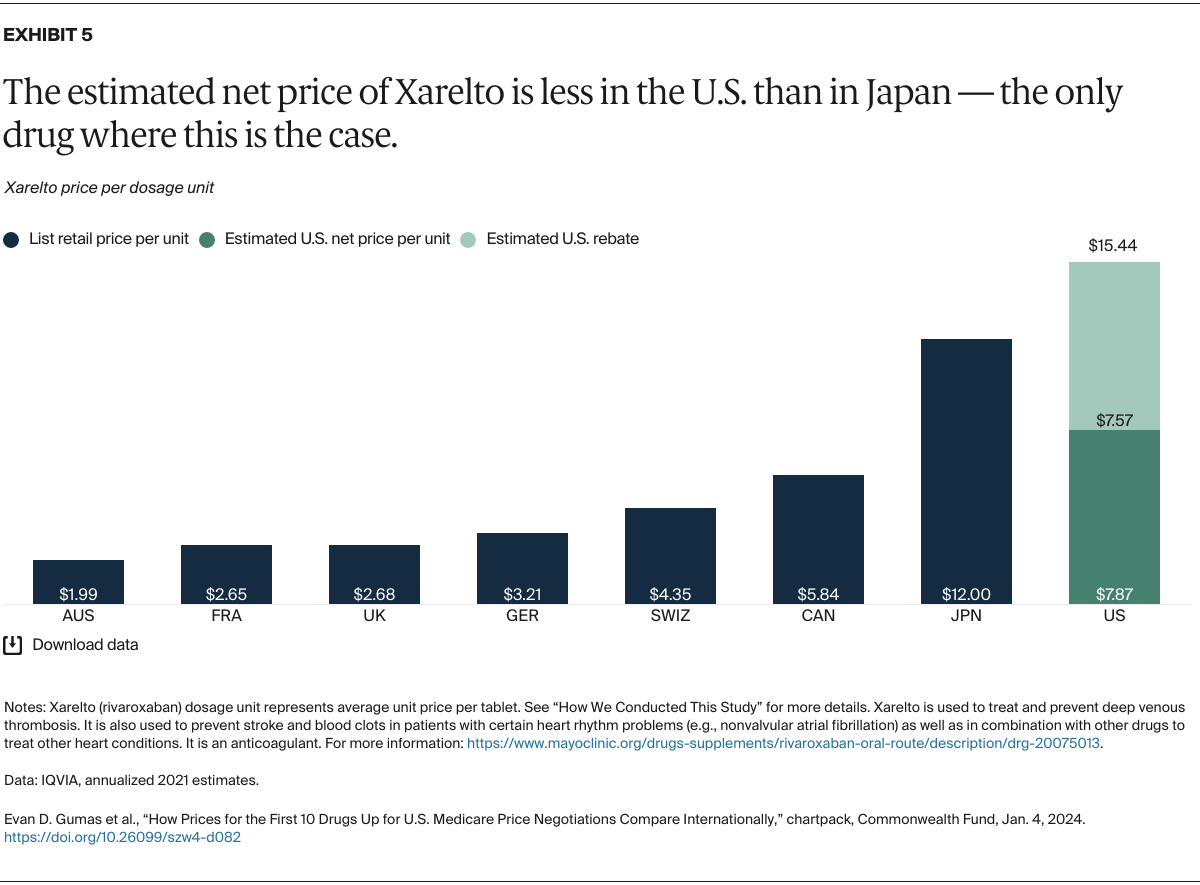

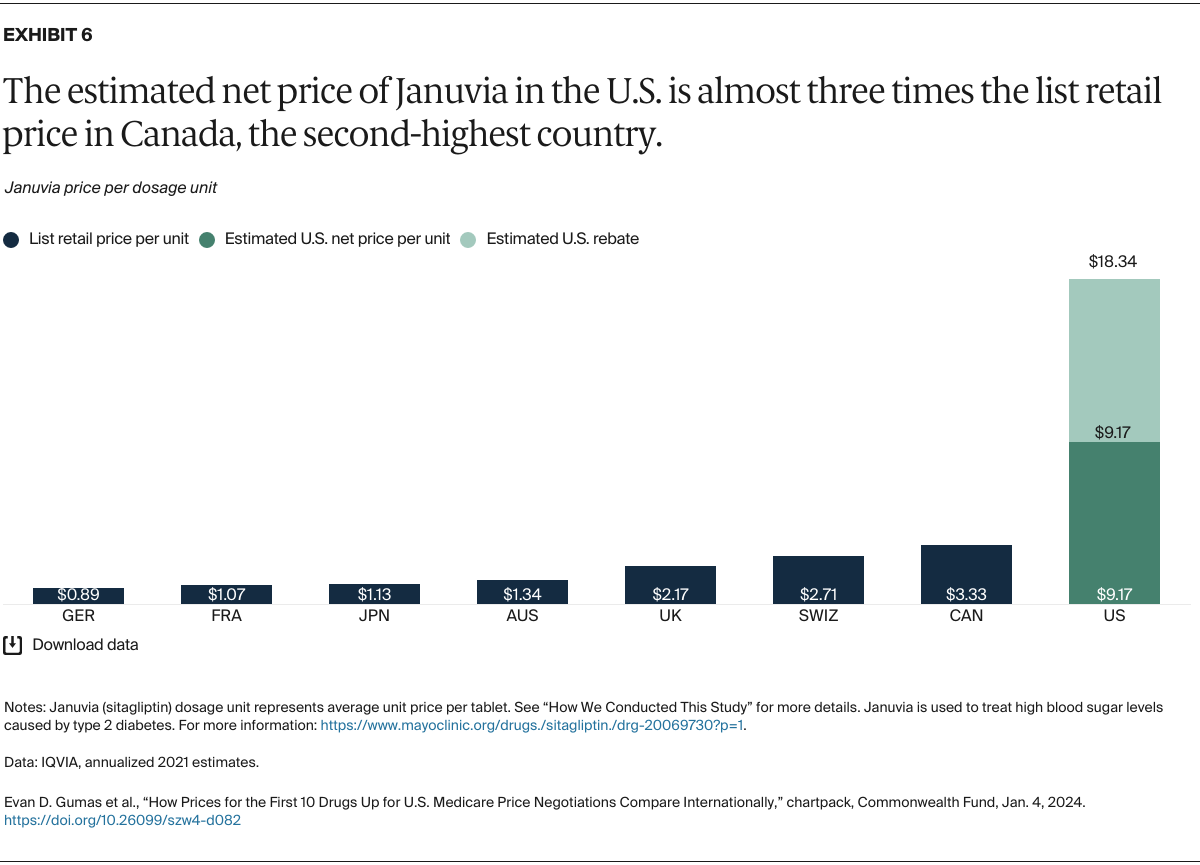

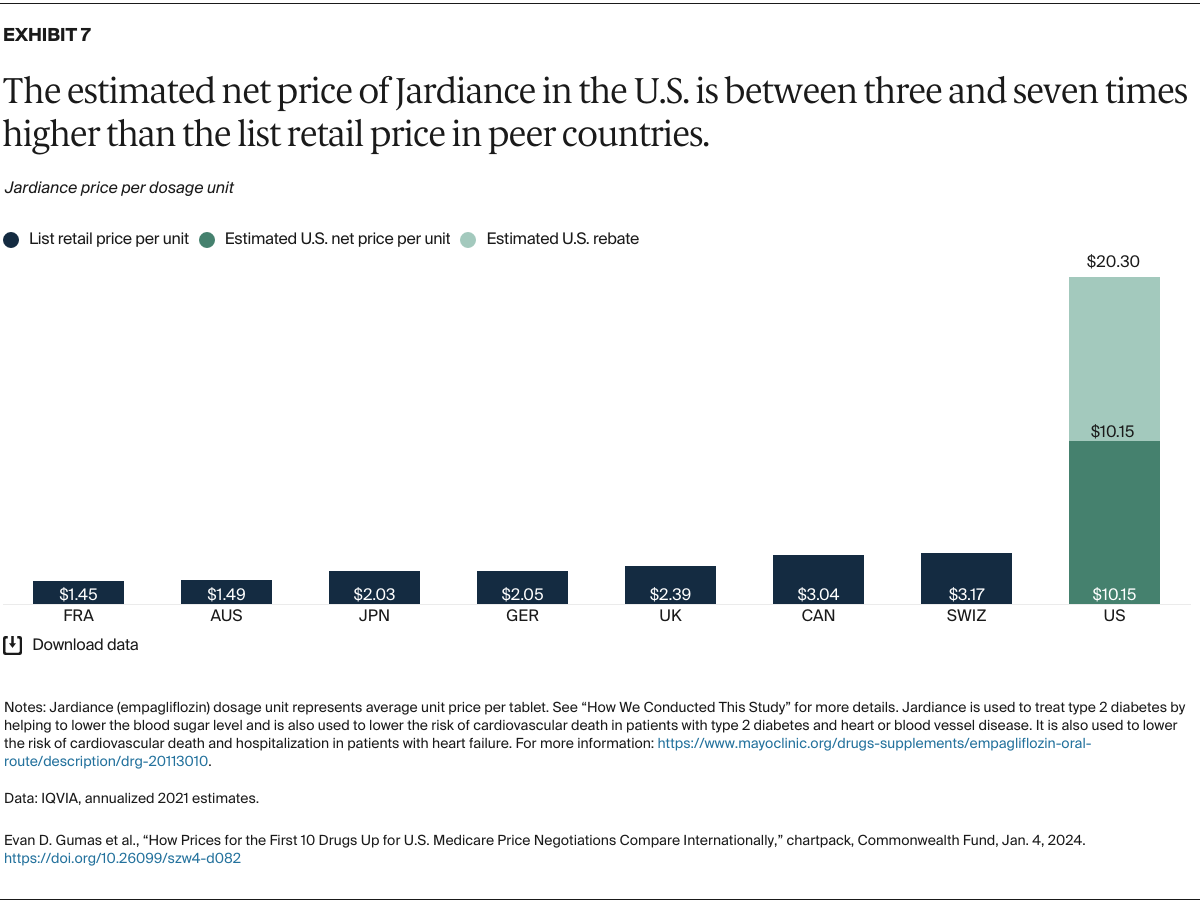

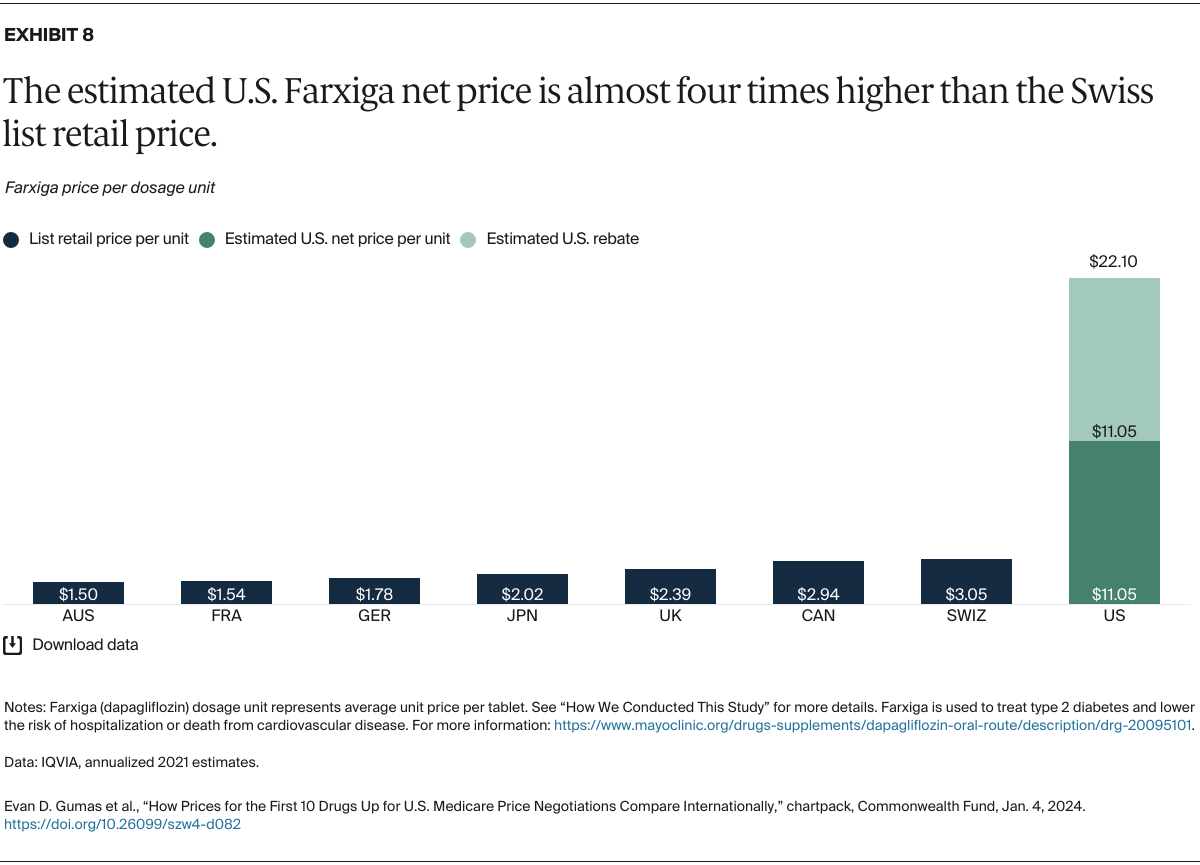

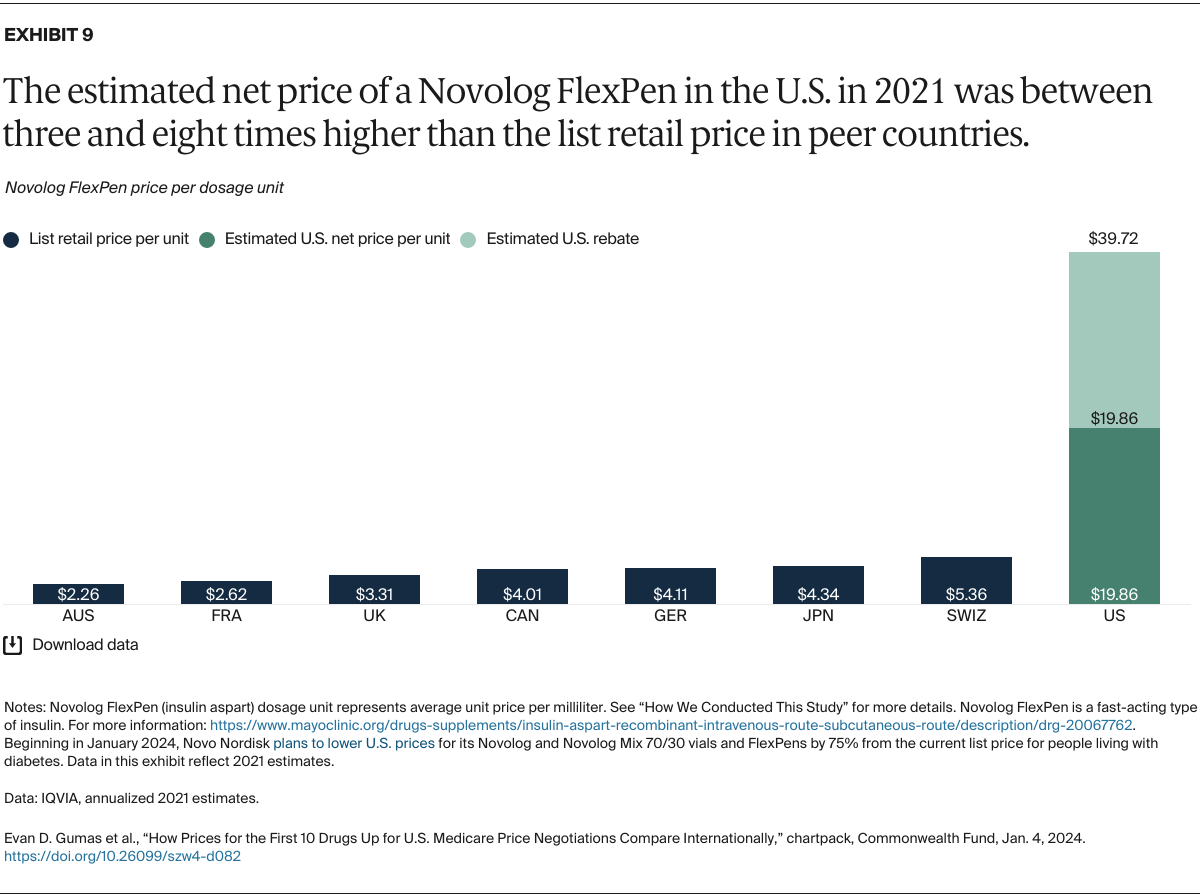

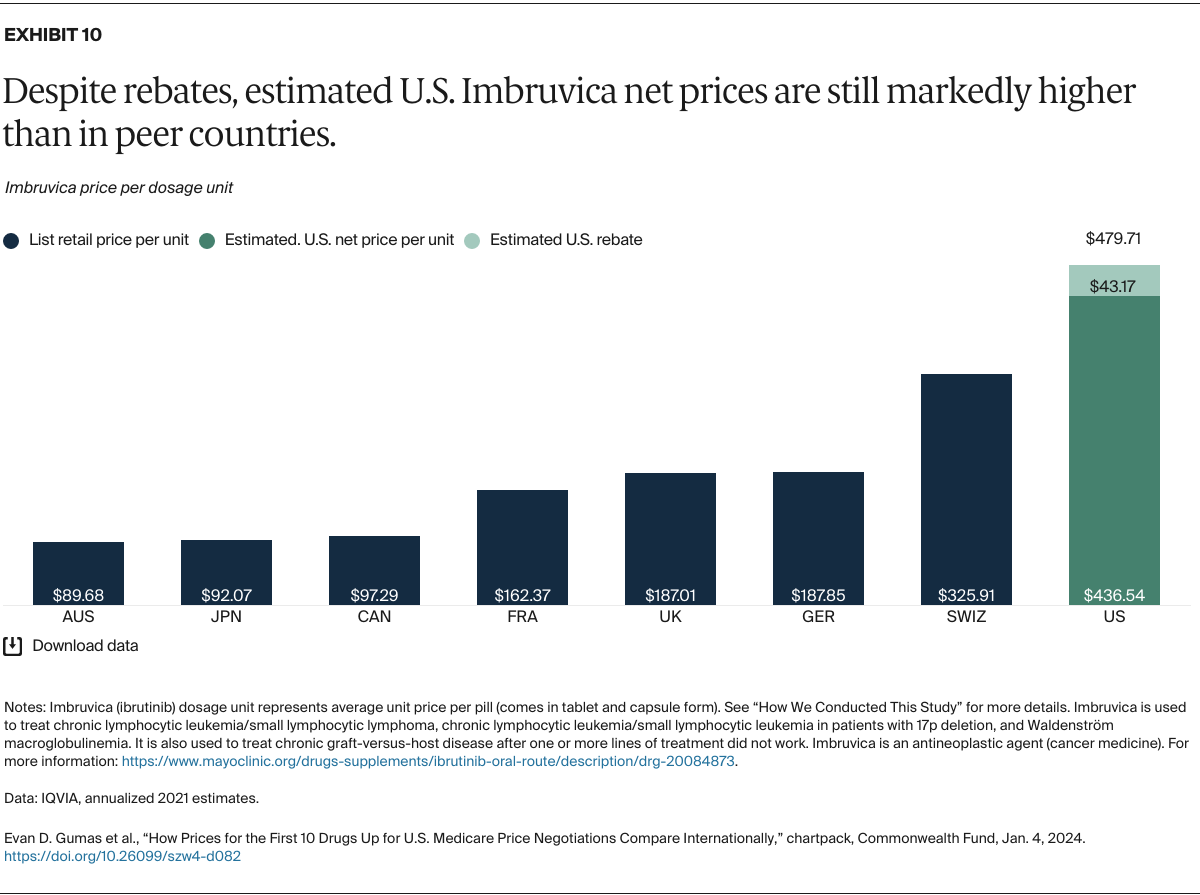

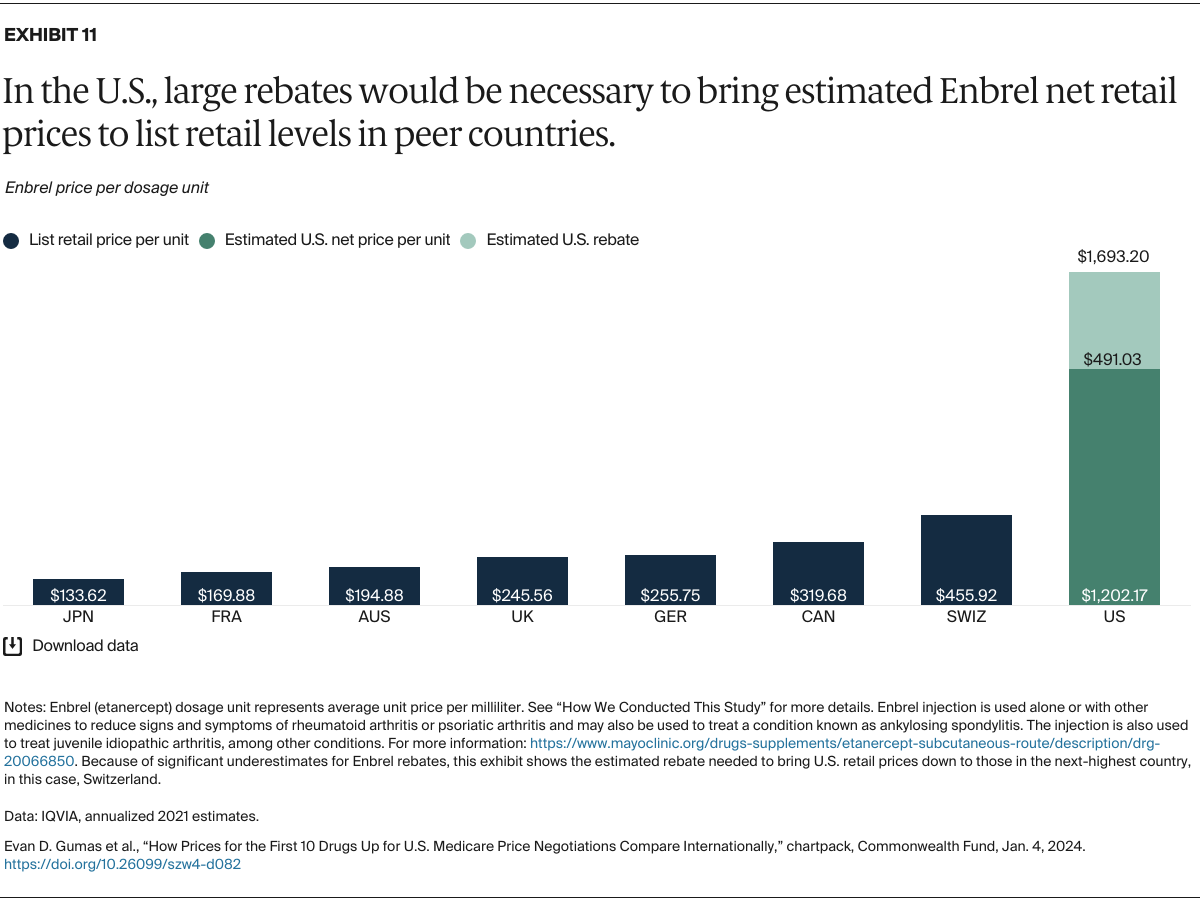

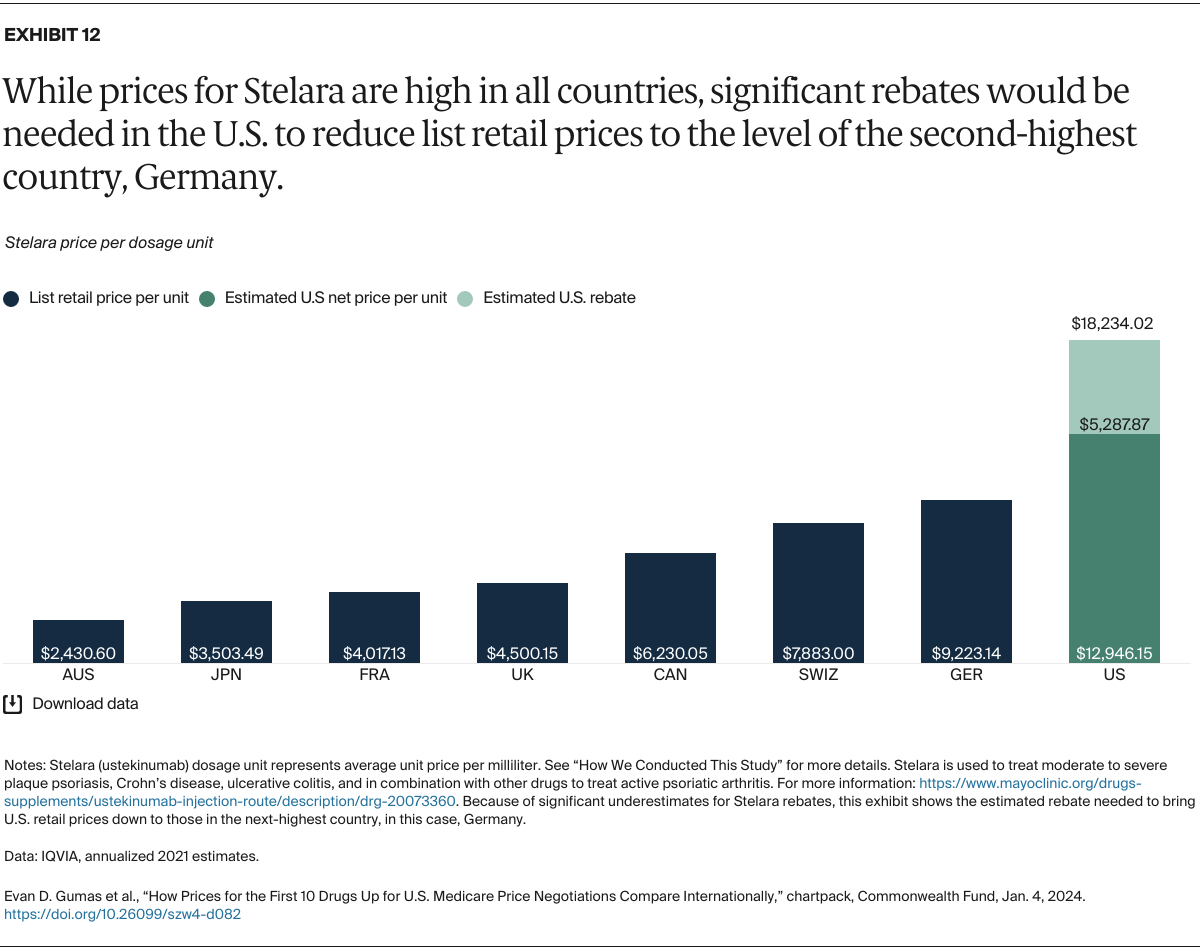

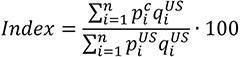

Understanding drug pricing and policy in peer countries — where drug use is similar but costs are lower — is important for benchmarking drug affordability going into the negotiation process.8 In the following charts, we look at list retail prices, which are prices charged by pharmacists to patients or insurers before any discounts, rebates, or other price reductions. List prices are a standard in international drug-pricing comparisons because of the lack of reliable data on net drug prices, which are prices that include rebates and discounts. Because of the exclusion of discounts or rebates, list prices likely overstate the prices paid by patients and insurers.9 But because list prices are set before country-specific discounts or rebates are applied, they are some of the only data points that can be systematically compared between countries. They are also the basis for discount negotiations.10 For drug prices in the United States, we also estimate net prices based on publicly available, therapeutic, classwide rebate estimates.11

The following charts draw on information made available by IQVIA, a firm that collects international comparative pharmaceutical data, and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, an independent congressional agency that advises the U.S. Congress on issues affecting the Medicare program (see “How We Conducted This Study” for more details and data methods).