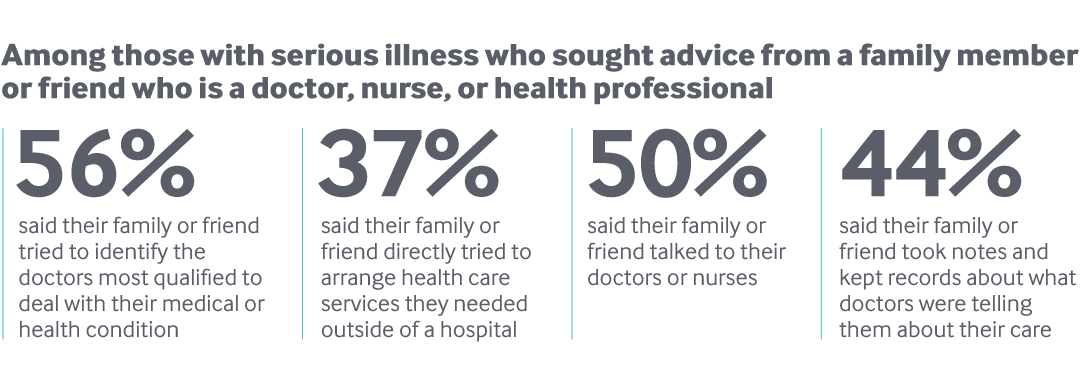

The luckiest among us have family and friends to lean on when times get tough. For those who develop a serious illness — an often painful and tumultuous experience — family and friends offer crucial emotional support and help with day-to-day activities. A recent survey of the sickest adults in America, conducted by the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, the New York Times, and the Commonwealth Fund, found that seriously ill adults also rely on their family and friends to organize their health care, helping them navigate an often complex, confusing, and inefficient system.

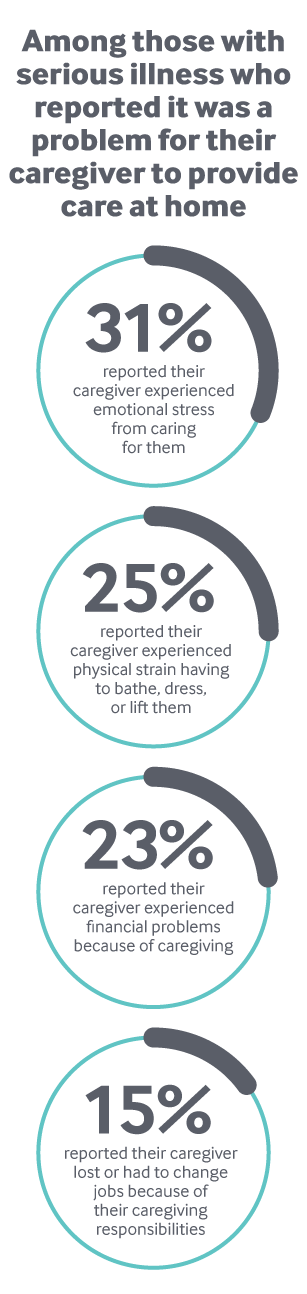

Focus groups and in-depth interviews conducted by the Commonwealth Fund since 2016 revealed that while taking care of a seriously ill family member or friend can bring meaning and satisfaction to caregivers, it also can become a complex and serious responsibility that burdens them.

Below we describe the many functions caregivers — defined as family and friends who provide care to the seriously ill — serve, as well as the financial, physical, and emotional challenges they face. We offer policy solutions, such as financial protections, employment flexibility, and training to prepare an “invisible workforce” for this deeply meaningful but sometimes overwhelming role.

Any one of us could find ourselves in the role of caregiver if we haven’t already. And our country and economy are likely to benefit when we help ensure caregivers are able to maintain their mental and physical health and stay in the workforce.