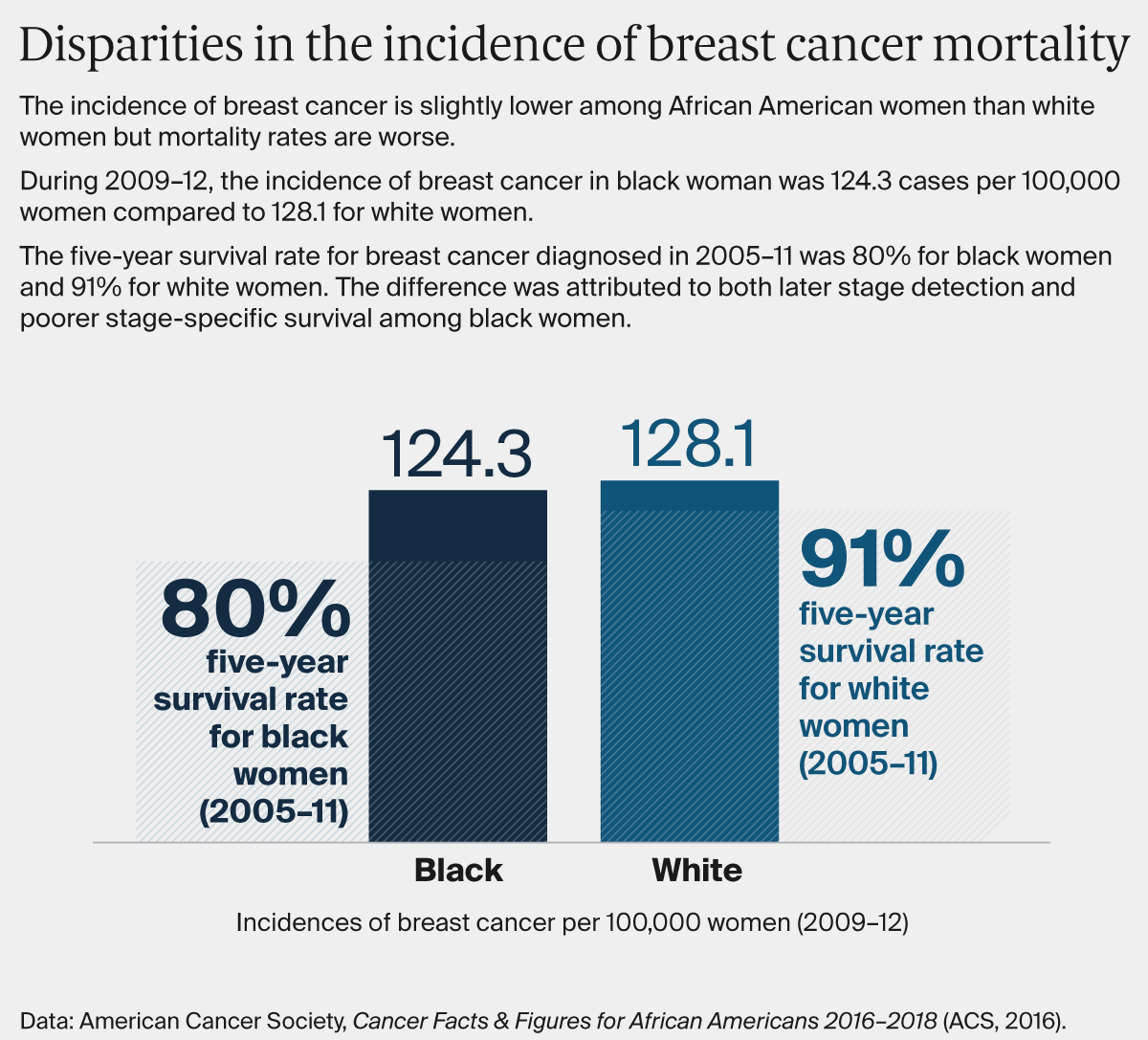

Compared with whites, members of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventive health services and often receive lower-quality care. They also have worse health outcomes for certain conditions. To combat these disparities, advocates say health care professionals must explicitly acknowledge that race and racism factor into health care. This issue of Transforming Care offers examples of health systems that are making efforts to identify implicit bias and structural racism in their organizations, and developing customized approaches to engaging and supporting patients to ameliorate their effects.

It’s been 15 years since the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s Unequal Treatment report, which synthesized a wide body of research demonstrating that U.S. racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive preventive medical treatments than whites and often receive lower-quality care. Most startling, the analysis found that even after taking into account income, neighborhood, comorbid illnesses, and health insurance type — factors typically invoked to explain racial disparities — health outcomes among blacks, in particular, were still worse than whites.

This research prompted the Institute of Medicine to add equity to a list of aims for the U.S. health care system, but efforts to ensure all Americans have equal opportunity to live long and healthy lives have been given less attention than have efforts to improve health care quality or reduce costs. A recent Institute for Healthcare Improvement white paper called equity “the forgotten aim,” noting as did the 2010 Institute of Medicine report, How Far Have We Come in Reducing Health Disparities?, how little progress has been made.

To reduce racial and ethnic health disparities, advocates say health care professionals must explicitly acknowledge that race and racism factor into health care. Less directed efforts to improve health outcomes, ones for instance that fail to consider the particular factors that may lead to worse outcomes for blacks, Hispanics, or other patients of color, may not lead to equal gains across groups — and in some cases may exacerbate racial health disparities.

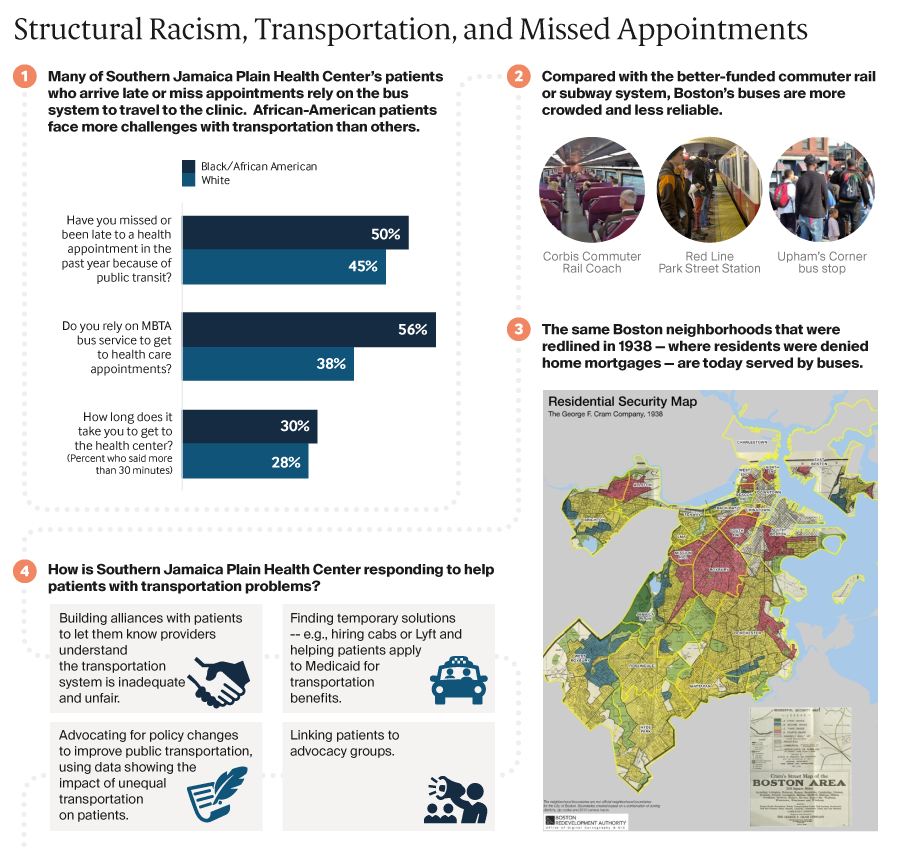

Addressing social factors like unstable housing that can lead to poor health is important, but it’s also necessary to acknowledge past and present policies — redlining, eviction procedures, and disinvestment in low-income communities for example — that fuel housing instability. “As health care organizations, payers, and others focus on social determinants and population health, we have a responsibility to ask: To what degree are our approaches grounded in a framework that addresses structural racism and equity?” says Rishi Manchanda, M.D., president and CEO of Health Begins, a nonprofit that helps health care and community organizations address social determinants of health.1 “If we can’t answer that question with rigor and candor, even our most innovative solutions might perpetuate inequity and illness, not prevent it.”

In this issue of Transforming Care, we consider the roles of implicit bias and structural racism in creating and perpetuating racial health disparities. Implicit bias refers to learned stereotypes and prejudices that operate automatically and unconsciously, while structural racism takes into account the many ways societies foster racial discrimination through housing, education, employment, media, health care, criminal justice, and other systems. We focus on these factors more than interpersonal racism, or negative feelings or prejudices that play out between individuals, because while the latter is important the former are more likely to be undetected or unacknowledged factors. We offer examples of health systems that are making deliberate efforts to identify how implicit bias and structural racism play a role in their work, and developing customized approaches to engaging and supporting patients to ameliorate their effects. Many are taking part in the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Pursuing Equity Initiative or have been recognized by the American Hospital Association’s Equity of Care Awards. Most of our examples relate to health disparities among black patients; we’ll delve into health disparities among Hispanics in a future issue.

Addressing Racial Disparities in Cancer Treatment

Greensboro, N.C., is remembered as the site of one of the first “sit-ins” of the Civil Rights movement. In 1960, a group of black college students refused to leave a whites-only Woolworth’s lunch counter, coming back day after day. The incident garnered widespread attention and prompted similar protests across the South. The city’s role in desegregating health care is less well known. In 1962, George Simkins, Jr., a Greensboro dentist, and other black dentists, physicians, and patients filed a lawsuit claiming that federal support for the Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and Wesley Long Hospital, local institutions that served only white patients, was unconstitutional. (One of Simkins’ patients had an abscessed tooth and needed surgery; Greensboro’s black hospital didn’t have space for him and the whites-only hospitals refused to treat him.) While the plaintiffs initially lost, they appealed, resulting in the Supreme Court decision, Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Hospital, that set in motion the desegregation of hospitals throughout the South.

In 2003, a group of Greensboro community organizers invited researchers from the University of North Carolina School of Public Health to form the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative, an effort to understand and address the lingering effects of segregation. One of the group’s first activities was to conduct focus groups among black and white members about their health care experiences. Many said they had experienced discrimination in a health care setting, with several stories relating to women’s experiences with breast cancer treatment.

The group then conducted a study exploring how widespread such experiences were, and whether they affected breast cancer treatment outcomes. Community members helped develop the research questions, conduct interviews, and analyze the results. “This was an important piece of the collaborative,” says Christina Yongue, M.P.H., coordinator of the Greensboro Cancer Care and Racial Equity study. “We made sure the community had full participation in every step of the research process. This was because of historical distrust among black Greensboro residents for Cone hospital, and because of more general distrust of clinical research going back to Tuskegee.”

After this initial research, the collaborative sought to test whether customized supports could improve the experiences of black women undergoing treatment for early-stage breast cancer. They also examined the experiences of black men or women with early-stage lung cancer, in part to see whether black women’s experiences with breast cancer treatment were related to their gender as much as race. The Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative partnered with Cone Health’s Wesley Long Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s Hillman Cancer Center in a project known as ACCURE (Accountability for Cancer Care Through Undoing Racism and Equity). Patients were randomly selected and invited to join the ACCURE study and then randomized into intervention and control groups. They found that at both cancer centers, black men and women with early-stage breast or lung cancer were less likely to complete treatment than white patients (81% of black patients completed treatment, compared with 87% of white patients), even after taking into account patients’ age, comorbid illnesses, health insurance, income, and marital status.

As a first step in addressing these disparities, all staff members at the two cancer centers were offered training from the Racial Equity Institute, which included sessions on racial disparities documented in the national cancer registry and the roles of racial bias and gatekeeping in health care. Staff and members of the collaborative also mapped out the steps of cancer treatment, from diagnosis through treatment and recovery, and then interviewed patients to understand points of breakdown. Several black women who had survived breast cancer said they had experienced poor treatment, including instances when physicians didn’t take time to explain their diagnoses and options, front-desk staff who treated them with disrespect, and lack of support in dealing with complications. A real-time patient registry, including data stratified by patients’ race, was created to track missed appointments and treatment milestones, and a physician champion shared clinical outcomes with his colleagues.

Specially trained ACCURE nurse navigators worked with patients to ensure they understood their treatment options and had financial and social supports. When a patient missed an appointment or treatment milestone (e.g., their first chemotherapy infusion), the navigator received an alert and reached out to investigate the reason and offer help with common problems, including financial concerns related to insurance approvals, juggling family schedules, or handling pain and other symptoms. Prior to this intervention, navigators would offer patients a notebook of resources, but typically not follow up unless patients made a request. “Someone would have to have a lot of health literacy to understand all of the things in the notebook and feel empowered enough to reach out,” says Yongue. “The model did not make it easy for a patient going through a traumatic experience.” The navigators worked with patients for up to three years, from diagnosis through treatment and recovery.

In some cases, the ACCURE navigator worked to overcome patients’ distrust, says Beth Smith, R.N., who serves as Cone Health Cancer Center’s patient navigation program manager. “I had a patient tell me that she heard there is a cure for cancer and they are keeping it from patients,” Smith says. “I talked with her about how her care team did not want to see her or any patient suffer and we’re here to do whatever is needed to care for her.”

After the ACCURE study, treatment completion rates increased among all patients, but they increased more among the intervention group, with 91 percent of black patients and 89 percent of white patients finishing their cancer treatment.

Promoting Cancer Screening Among Racial and Ethnic Minorities

Cone Health and other cancer care providers also have worked to address racial disparities in cancer outcomes by encouraging patients of color to obtain regular screenings. Minneapolis-based HealthPartners, which has been stratifying data on its patients’ experiences and outcomes by race and ethnicity for more than a dozen years, found that rates of screening for colorectal cancer among minority patients lagged rates among white patients (in 2009, 43% of patients of color who were candidates for screening completed it vs. 69.2% of white patients).

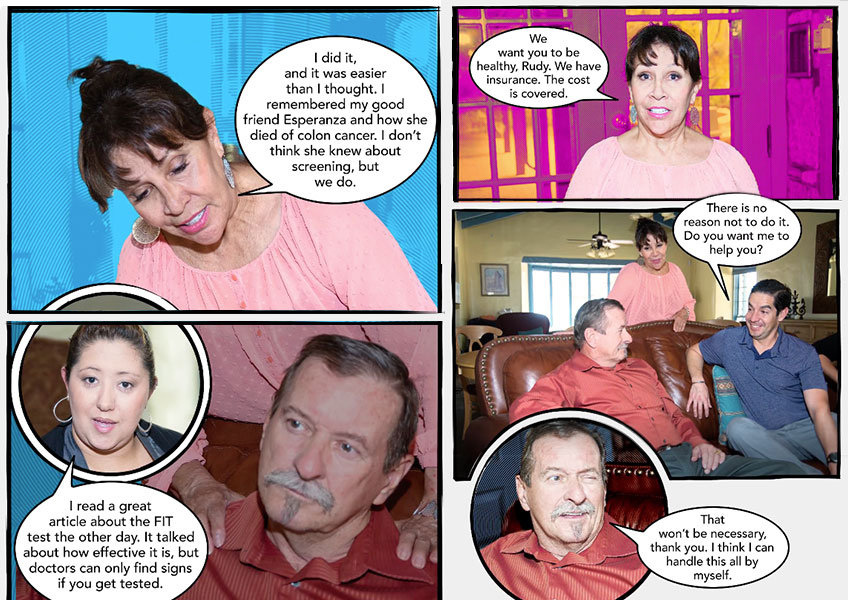

Focus group research uncovered concerns among many minority patients about the invasiveness and inconvenience of the traditional colonoscopy. Over the years, HealthPartners has leveraged several different tools to try to decrease the gap, including adding decision support and proactively reaching out to patients. In August 2017, the health system sent a home colon cancer screen, known as FIT (fecal immunochemical test), to more than 3,000 patients of color.2 They also encouraged physicians to avoid describing the traditional colonoscopy as the “gold standard” of screening because it implied FIT was inferior when the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force made no distinction. By the end of 2017, three months after this intervention began, an additional 757 more patients of color had been screened. Altogether, the gap in screening rates between white patients and patients of color narrowed significantly, from 77.7 percent for white patients to 70.1 percent for patients of color. HealthPartners hopes to continue building on this momentum and has plans for continued FIT mailings.

Kaiser Permanente has taken a similar approach to encouraging more patients of color to get screened for colorectal cancer; in 2009, screening rates among Latino members, in particular, lagged white members by 5 percentage points. After doing ethnographic research that suggested some racial and ethnic minorities were concerned about taking time off work for a colonoscopy and were more likely to respond to a message about treating cancer rather than finding it, Kaiser Permanente created photo novellas (animated comics using photographs) depicting Latino family members trying to convince their loved one to use FIT. This and other initiatives led to an increase in colorectal cancer screening among Latino patients from 65.7 percent in 2009 to 77.3 percent in 2018 (compared to 80% among whites).

Improving Control of Chronic Conditions

Kaiser Permanente also has sought to improve control of chronic conditions among minority patients, which required a different approach, according to Winston Wong, M.D., the health system’s medical director of community benefit and director of disparities improvement and quality initiatives. While something like cancer screening happens once every few years, chronic care management “requires a continuous care relationship that builds around issues of trust,” he says.

Kaiser Permanente also has focused on disparities that have a high cost in terms of illness and death. For example, it has reduced the gap between white and black patients with controlled hypertension. “That was really important to us because it represents real morbidity, real mortality — people dying of strokes and heart attacks that could have been prevented if their blood pressure were controlled,” Wong says.

As part of the effort, which spanned eight regions, Kaiser Permanente’s clinicians sought to counter misconceptions reported by some black patients that dying from high blood pressure is “natural” by encouraging clinicians to be clear about the risks and dogged in their efforts to encourage patients to come in for treatment. It also has partnered with the American Heart Association on the national Check. Change. Control. campaign, which seeks to reduce disparities in blood pressure control by empowering people to monitor their own blood pressure and encouraging others in their networks to do so. In San Diego, for example, parishioners in 20 predominantly black churches were trained in how to monitor their blood pressure and coach others.

Between 2009 and 2017, Kaiser increased the percentage of African Americans whose hypertension was controlled from 75.3 percent to 89.6 percent, bringing the rate within 2.2 percentage points of the rate among white members.

Targeting Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

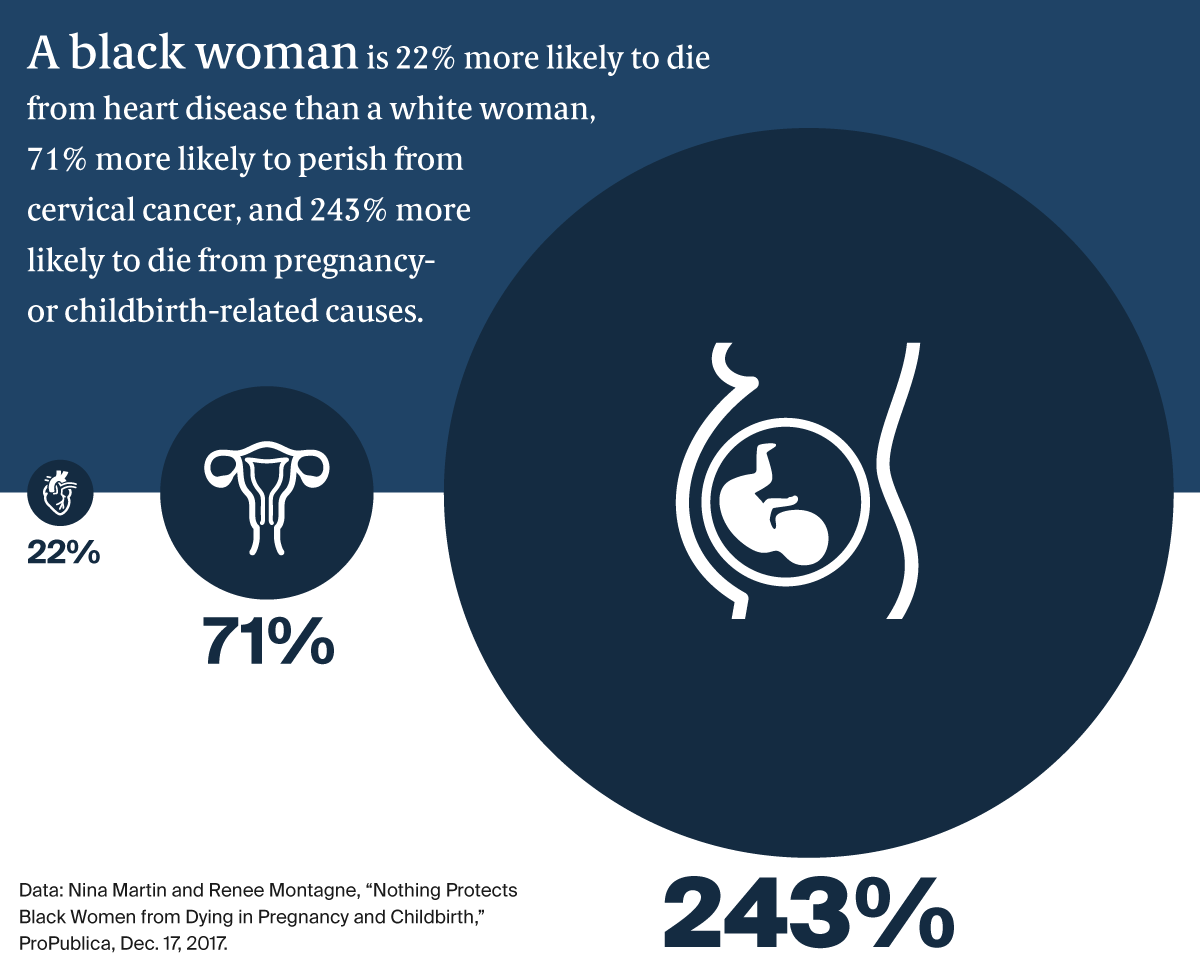

Serena Williams’s postpartum complications and the story of Shalon Irving, an epidemiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who studied racial disparities in health care and died three weeks after giving birth from complications of high blood pressure, have focused attention on racial disparities in maternal mortality and morbidity (e.g., deaths or complications related to pregnancy and childbirth). Black mothers die from pregnancy-related complications at three to four times the rate of white women. And while maternal mortality has been dropping in Sub-Saharan Africa, rates actually increased in the United States from 2000 to 2014. Socioeconomic status, education, and other factors do not appear to protect black women from this risk, while factors including smoking, drug abuse, and obesity do not explain the differences.

These findings have led some health care researchers to suggest that the experience of being a black woman in America is, itself, a risk factor — and that attention must be paid both to black women’s level of stress throughout their lives and how they are treated by health care professionals. “There’s often an assumption in the medical world that racial disparities are due to something genetic, when in fact it might be racism,” says Neel Shah, M.D., assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School. “We’re taught that racism is evil so it’s hard to recognize that in ourselves. But the studies suggest, for example, that we believe black women less when they express symptoms, and we tend to undervalue their pain.”

Some health systems and departments of health are working to address these disparities, often by offering women of color the support of doulas or more closely monitoring them after delivery, a point of vulnerability evident in a report on maternal mortality reviews in nine states that found pregnancy-related deaths occurred more commonly within 42 days of giving birth than during pregnancy.

In 2013, marriage and family therapist and midwife Aza Nedhari, M.S., founded Mamatoto Village (Mamatoto means “the connection between mother and baby” in Swahili) in Washington, D.C. Her goal was to create a custom model of support for women of color during their pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum periods. Nedhari believes that typical doula training — a matter of a few days — is insufficient to address black women’s cultural needs or their comprehensive health needs. Instead, Mamatoto has adopted the community health worker (CHW) model, recruiting mothers from the neighborhoods Mamatoto serves and offering them two years of training, mentorship, and field work. The CHWs then specialize in one of three paths: 1) helping women with social problems (e.g., domestic violence or housing instability), 2) helping them initiate and sustain breastfeeding, or 3) helping them manage their health and wellness.

So far, four managed care organizations pay for their members to receive Mamatoto’s services. Last year, among 462 women served by the organization, 74 percent gave birth vaginally (compared with 69 percent of women nationally) and there were no infant or maternal losses. Ninety-two percent of women who received labor support attended their six-week postpartum appointment, and 89 percent were able to initiate breastfeeding (compared with 79 percent of women nationally). The average weight for newborns of mothers who received prenatal and labor support was 6.98 lbs. in 2017, compared with 6.07 lbs. for newborns of mothers who entered the program after giving birth. For more information about Mamatoto Village, read our interview with Nedhari.

The first obstacle we find is that organizations don’t have a shared definition of racism, so it is hard to even talk about it. If you think that racism is merely people saying mean things to each other and I think it is a system of advantage based on race it will be impossible to co-design any solutions together.