By Ryozo Matsuda, College of Social Sciences, Ritsumeikan University

Japan’s statutory health insurance system provides universal coverage. It is funded primarily by taxes and individual contributions. Enrollment in either an employment-based or a residence-based health insurance plan is required. Benefits include hospital, primary, specialty, and mental health care, as well as prescription drugs. In addition to premiums, citizens pay 30 percent coinsurance for most services, and some copayments. Young children and low-income older adults have lower coinsurance rates, and there is an annual household out-of-pocket maximum for health care and long-term services based on age and income. There are also monthly out-of-pocket maximums. The national government sets the fee schedule. Japan’s prefectures develop regional delivery systems. Most residents have private health insurance, but it is used primarily as a supplement to life insurance, providing additional income in case of illness.

Sections

How does universal health coverage work?

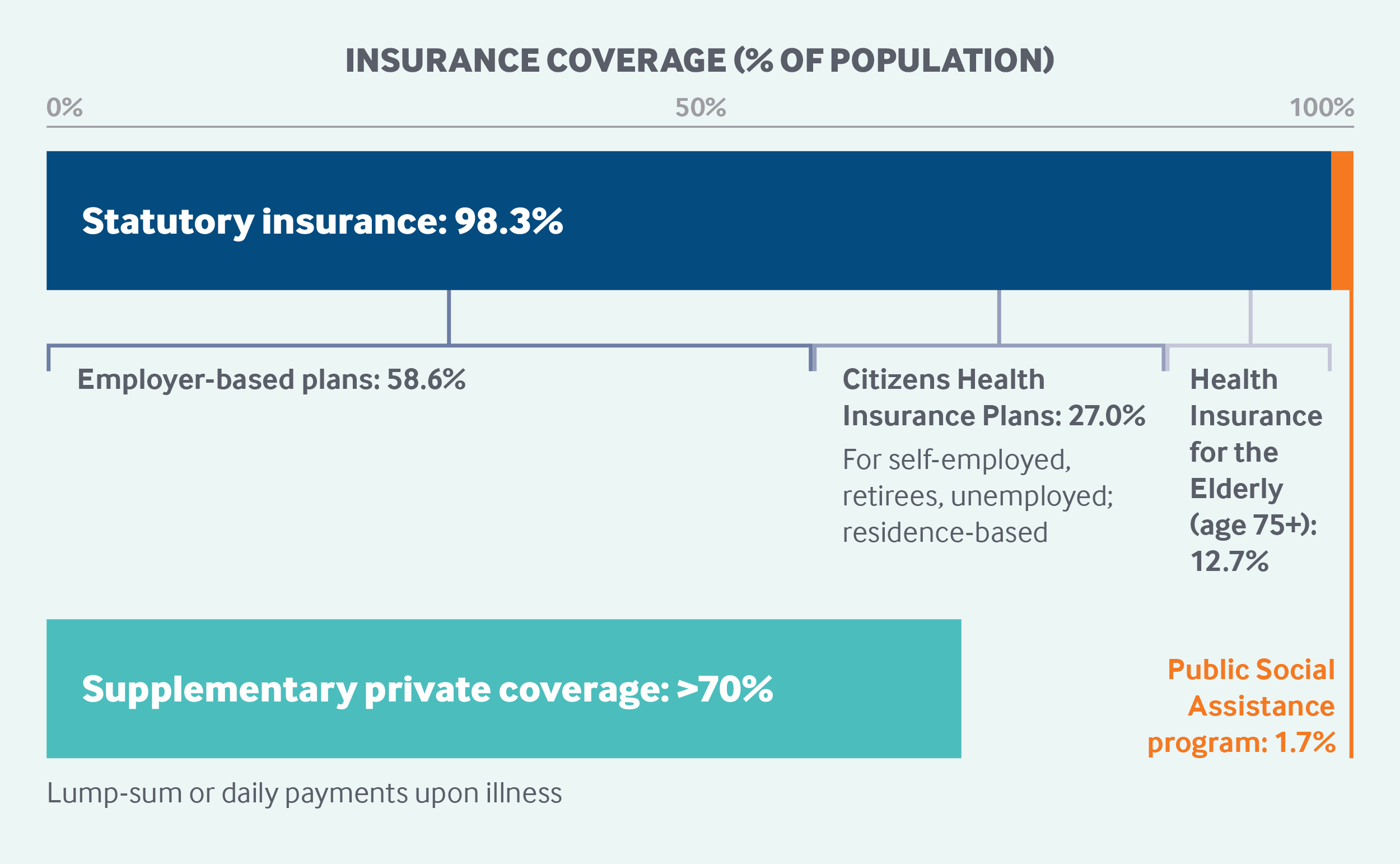

Japan’s statutory health insurance system (SHIS) covers 98.3 percent of the population, while the separate Public Social Assistance Program, for impoverished people, covers the remaining 1.7 percent.1,2 Citizens and resident noncitizens are required to enroll in an SHIS plan; undocumented immigrants and visitors are not covered.

The SHIS consists of two types of mandatory insurance:

- employment-based plans, which cover about 59 percent of the population

- residence-based insurance plans, which include Citizen Health Insurance plans for nonemployed individuals age 74 and under (27% of the population) and Health Insurance for the Elderly plans, which automatically cover all adults age 75 and older (12.7% of the population).

Each of Japan’s 47 prefectures, or regions, has its own residence-based insurance plan, and there are more than 1,400 employment-based plans.3

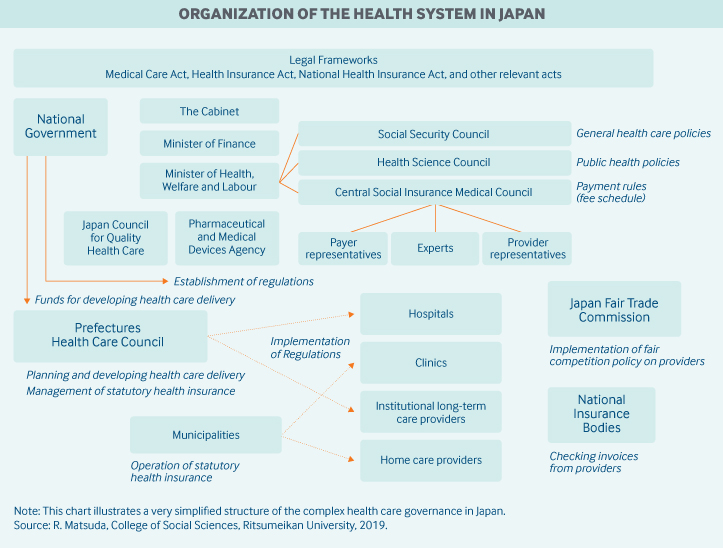

Role of government: The national and local governments are required by law to ensure a system that efficiently provides good-quality medical care. The national government regulates nearly all aspects of the SHIS. National government sets the SHIS fee schedule and gives subsidies to local governments (municipalities and prefectures), insurers, and providers. It also establishes and enforces detailed regulations for insurers and providers.

Japan’s prefectures implement national regulations, manage residence-based regional insurance (for example, by setting contributions and pool funds), and develop regional health care delivery networks with their own budgets and funds allocated by the national government. The more than 1,700 municipalities are responsible for organizing health promotion activities for their residents and assisting prefectures with the implementation of residence-based Citizen Health Insurance plans, for example, by collecting contributions and registering beneficiaries.4

Government agencies involved in health care include the following:

- the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, which drafts policy documents and makes detailed regulations and rules once general policies are authorized

- the Social Security Council, which is in charge of developing national strategies on quality, safety, and cost control, and sets guidelines for determining provider fees

- the Central Social Insurance Medical Council, which defines the benefit package and fee schedule

- the Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices Agency, which reviews pharmaceuticals and medical devices for quality, efficacy, and safety

- the Central Social Insurance Medical Council, which sets the SHIS list of covered pharmaceuticals and their prices.5

Role of public health insurance: In 2015, estimated total health expenditures amounted to approximately 11 percent of GDP, of which 84 percent was publicly financed, mainly through the SHIS.6 Funding of health expenditures is provided by taxes (42%), mandatory individual contributions (42%), and out-of-pocket charges (14%).7

In employment-based plans, employers and employees share mandatory contributions. The contribution rates are about 10 percent of both monthly salaries and bonuses and are determined by an employee's income. Contribution rates are capped. In Tokyo, the maximum monthly salary contribution in 2018 was JPY 137,000 (USD 1,370) and the maximum contribution taken from bonuses was JPY 5,730,000 (USD 57,300).8,9,10 These contributions are tax-deductible, and vary between types of insurance funds and prefectures. For residence-based insurance plans, the national government funds a proportion of individuals’ mandatory contributions, as do prefectures and municipalities. The Japan Health Insurance Association, which insures employers and employees of small and medium-sized companies, and health insurance associations that insure large companies also contribute to Health Insurance for the Elderly plans. Finally, there are complex cross-subsidies among and within the different SHIP plans.11

The Public Social Assistance Program, separate from the SHIS, is paid through national and local budgets.

Role of private health insurance: Although the majority (more than 70%) of the population holds some form of secondary, voluntary private health insurance,12 private plans play only a supplementary or complementary role. Historically, private insurance developed as a supplement to life insurance. It provides additional income in case of sickness, usually as a lump sum or in daily payments over a defined period, to sick or hospitalized insured persons.

The number of supplementary medical insurance policies in force has gradually increased, from 23.8 million in 2010 to 36.8 million in 2017.13 The provision of privately funded health care has been limited to services such as orthodontics. Both for-profit and nonprofit organizations operate private health insurance.

Part of an individual’s life insurance premium and medical and long-term care insurance contributions can be deducted from taxable income.14 Employers may have collective contracts with insurance companies, lowering costs to employees.

Services covered: All SHIS plans provide the same benefits package, which is determined by the national government:

- hospital visits

- primary and specialty care

- mental health care

- approved prescription drugs

- home care services provided by medical institutions

- hospice care

- physical therapy

- most dental care.

The SHIS does not cover corrective lenses unless they’re prescribed by physicians for children up to age 9. Optometry services provided by nonphysicians also are not covered.

Although maternity care is generally not covered, the SHIS provides medical institutions with a lump-sum payment for childbirth services. In addition, local governments subsidize medical checkups for pregnant women.

Home care services provided by nonmedical institutions are covered by long-term care insurance (LTCI) (see “Long-term care and social supports” below).

Durable medical equipment prescribed by physicians (such as oxygen therapy equipment) is covered by SHIS plans. People with disabilities who need other equipment like hearing aids or wheelchairs receive government subsidies to help cover the cost.

Select preventive services, including some screenings and health education, are covered by SHIS plans, while cancer screenings are delivered by municipalities.

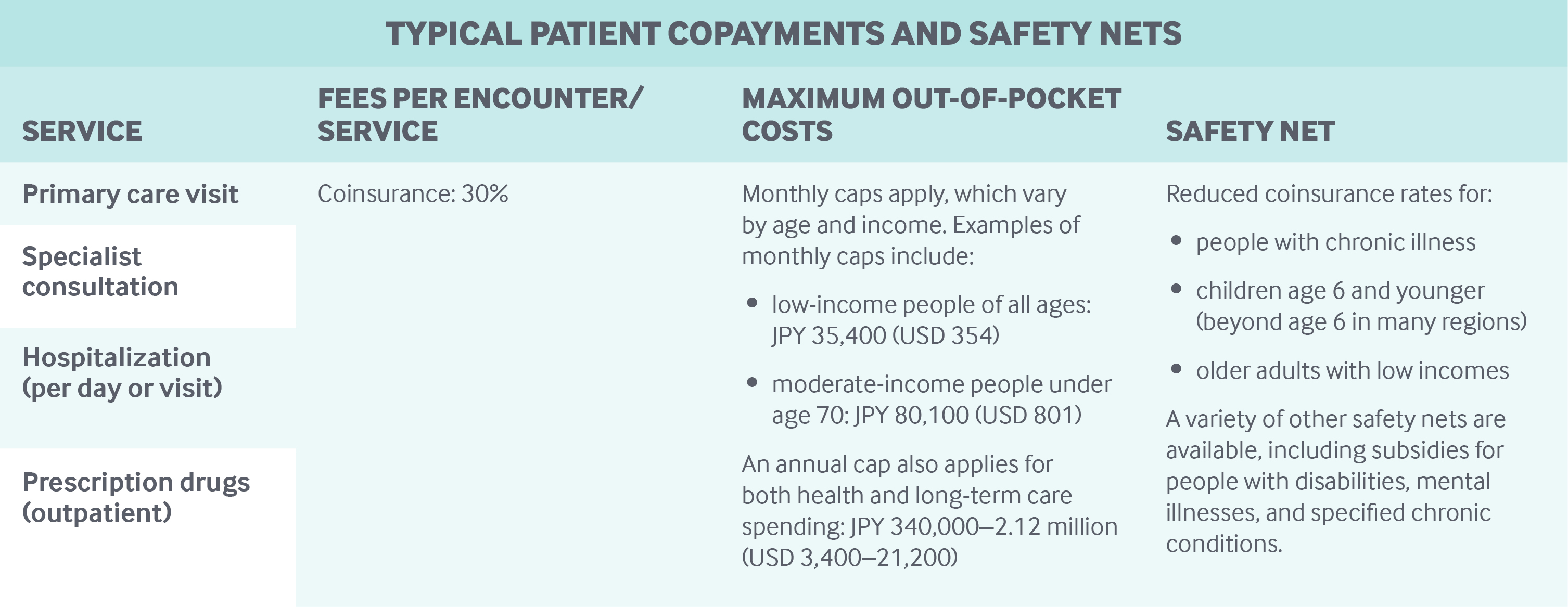

Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending: In 2015, out-of-pocket payments accounted for 14 percent of current health expenditures. There are no deductibles, but SHIS enrollees pay coinsurance and copayments.

SHIS enrollees have to pay 30 percent coinsurance for all health services and pharmaceuticals; young children and adults age 70 and older with lower incomes are exempt from coinsurance.

Small copayments are charged for primary care and specialty visits (see table). Residents also pay user charges for preventive services, such as cancer screenings, delivered by municipalities.

Providers are prohibited from balance billing or charging fees above the national fee schedule, except for some services specified by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, including experimental treatments, outpatient services of large multispecialty hospitals, after-hours services, and hospitalizations of 180 days or more.

Safety nets: In the SHIS, catastrophic coverage stipulates a monthly out-of-pocket threshold, which varies according to enrollee age and income. For example, the monthly maximum for people under age 70 with modest incomes is JPY 80,100 (USD 801); above this threshold, a 1 percent coinsurance rate applies. Low-income people do not pay more than JPY 35,400 (USD 354) a month.

Subsidies (mostly restricted to low-income households) further reduce the burden of cost-sharing for people with disabilities, mental illnesses, and specified chronic conditions.

In addition, there is an annual household health and long-term care out-of-pocket ceiling, which varies between JPY 340,000 (USD 3,400) and JPY 2.12 million (USD 21,200) per enrollee, according to income and age. Above this ceiling, all payments can be fully reimbursed.

People can deduct annual expenditures on health services and goods between JPY 100,000 (USD 1,000) and JPY 2 million (USD 20,000) from taxable income. In addition, expenditures for copayments, balance billing, and over-the-counter drugs are allowable as tax deductions.

Other safety nets for SHIS enrollees include the following:

- Enrollees in employment-based plans who are on parental leave are exempt from paying monthly mandatory salary contributions.

- Enrollees in Citizen Health Insurance plans who have relatively lower incomes (such as the unemployed, the self-employed, and retirees) and those with moderate incomes who face sharp, unexpected income reductions are eligible for reduced mandatory contributions.

- Reduced coinsurance rates apply to patients with one of the 306 designated long-term diseases if they use designated health care providers. The reduced rates vary by income.

- Approved providers are allowed to reduce coinsurance for low-income people through the Free/Lower Medical Care Program.

Low-income people in the Public Social Assistance Program do not incur any user charges.15

How is the delivery system organized and how are providers paid?

Physician education and workforce: The number of people enrolling in medical school and the number of basic medical residency positions are regulated nationally. The number of residency positions in each region is also regulated.

Approximately two-thirds of medical students study at public medical schools, while the remaining one-third are enrolled at private schools. Total tuition fees for a public six-year medical education program are around JPY 3.5 million (USD 35,000). Total private school tuition is JPY 20 million–45 million (USD 200,000–450,000).16

Since the mid-1950s, the government has been working to increase health care access in remote areas. Recent measures include subsidies for local governments in those areas to establish and maintain health facilities and develop student-loan forgiveness programs for medical professionals who work in their jurisprudence. Most of these measures are implemented by prefectures.17

Primary care: Historically, there has been no institutional or financial distinction between primary care and specialty care in Japan. The idea of “general practice” has only recently developed.

Primary care is provided mainly at clinics, with some provided in hospital outpatient departments. Most clinics (83% in 2015) are privately owned and managed by physicians or by medical corporations (health care management entities usually controlled by physicians). A smaller proportion are owned by local governments, public agencies, and not-for-profit organizations.

Primary care practices typically include teams with a physician and a few employed nurses. In 2014, the average clinic had 6.8 full-time-equivalent workers, including 1.3 physicians, 2.0 nurses, and 1.8 clerks.18 Nurses and other staff are usually salaried employees. In some places, nurses serve as case managers and coordinate care for complex patients, but duties vary by setting.

Clinics can dispense medication, which doctors can provide directly to patients. Use of pharmacists, however, has been growing; 73 percent of prescriptions were filled at pharmacies in 2017.19

Patients are not required to register with a practice, and there is no strict gatekeeping. However, the government encourages patients to choose their preferred doctors, and there are also patient disincentives for self-referral, including extra charges for initial consultations at large hospitals.

Payments for primary care are based on a complex national fee-for-service schedule, which includes financial incentives for coordinating the care of patients with chronic diseases (known as Continuous Care Fees) and for team-based ambulatory and home care. The schedule, set by the government, includes both primary and specialist services, which have common prices for defined services, such as consultations, examinations, laboratory tests, imaging tests, and defined chronic disease management. In some cases, providers can choose to be paid on a per-case basis or on a monthly basis. Bundled payments are not used. Providers are usually prohibited from balance billing, but can charge for some services (see “Cost-sharing and out-of-pocket spending” above).

Outpatient specialist care: Most outpatient specialist care is provided in hospital outpatient departments, but some is also available at clinics, where patients can visit without referral.

Fees are determined by the same schedule that applies to primary care (see above).

At hospitals, specialists are usually salaried, with additional payments for extra assignments, like night-duty allowances. Those working at public hospitals can work at other health care institutions and privately with the approval of their employers; however, even in such cases, they usually provide services covered by the SHIS.

The employment status of specialists at clinics is similar to that of primary care physicians. Physicians working at medium-sized and large hospitals, in both inpatient and outpatient settings, earned on average JPY 1,514,000 (USD 15,140) a month in 2017.20

Administrative mechanisms for direct patient payments to providers: Clinics and hospitals send insurance claims, mostly online, to financing bodies (intermediaries) in the SHIS, which pay a major part of the fees directly to the providers. Patients pay cost-sharing at the point of service.

After-hours care: After-hours care is provided by hospital outpatient departments, where on-call physicians are available, and by some medical clinics and after-hours care clinics owned by local governments and staffed by physicians and nurses.

The national government gives subsidies to local governments for these clinics. Hospitals and clinics are paid additional fees for after-hours care, including fees for telephone consultations.

Patients can walk in at most hospitals and clinics for after-hours care. Patient information from after-hours clinics is provided to family physicians, if necessary. Such information is often handed to patients to show to family physicians.

There is a national pediatric medical advice telephone line available after hours. In some regions and metropolitan areas, fire and emergency departments organize telephone emergency consultation with nurses and trained staff, supported by physicians.21

Hospitals: As of 2016, 15 percent of hospitals are owned by national or local governments or closely related agencies. The rest are private and nonprofit, some of which receive subsidies because they’ve been designated public interest medical institutions.22,23 The private sector has not been allowed to manage hospitals, except in the case of hospitals established by for-profit companies for their own employees.

Acute-care hospitals, both public and private, choose whether to be paid strictly under traditional fee-for-service or under a diagnosis-procedure combination (DPC) payment approach, which is a case-mix classification similar to diagnosis-related groups.24 The DPC payment consists of a per-diem payment for basic hospital services and less-expensive treatments and a fee-for-service payment for specified expensive services, such as surgical procedures or radiation therapy.25 Most acute-care hospitals choose the DPC approach. Episode-based payments involving both inpatient and outpatient care are not used.

Mental health care: Mental health care is provided in outpatient, inpatient, and home care settings, with patients charged the standard 30 percent coinsurance, reduced to 10 percent for individuals with chronic mental health conditions. Covered services include psychological tests and therapies, pharmaceuticals, and rehabilitative activities. Specialized mental health clinics and hospitals exist, but services for depression, dementia, and other common conditions are also provided by primary care.

Most psychiatric beds are in private hospitals owned by medical corporations.

Long-term care and social supports: National compulsory long-term care insurance (LTCI), administered by municipalities under the guidance of the national government, covers those age 65 and older, and people ages 40 to 64 who have select disabilities. LTCI covers:

- home care

- respite care

- services at long-term care facilities

- disability equipment

- assistive devices

- home modification.

End-of-life care is covered by the SHIS and LTCI. The SHIS covers hospice care (both at home and in facilities), palliative care in hospitals, and home medical services for patients at the end of life. Either the SHIS or LTCI covers home nursing services, depending on patients’ needs. Home help services are covered by LTCI.

Taxes provide roughly half of LTCI funding, with national taxes providing one-fourth of this funding and taxes in prefectures and municipalities providing another one-fourth.

The remaining LTCI funding comes from individual mandatory contributions set by municipalities; these are based on income (including pensions) as well as estimated long-term care expenditures in the resident’s local jurisdiction. Citizens age 40 and over pay income-related contributions in addition to SHIS contributions. Employers and employees split their contributions evenly.

A 20 percent coinsurance rate applies to all covered LTCI services, up to an income-related ceiling. For low-income people age 65 and older, the coinsurance rate is reduced to 10 percent. There is an additional copayment for bed and board in institutional care, but it is waived or reduced for low-income individuals. All costs for beneficiaries of the Public Social Assistance Program are paid from local and national tax revenue.26

The majority of LTCI home care providers are private. In 2016, 66 percent of home help providers, 47 percent of home nursing providers, and 47 percent of elderly day care service providers were for-profit, while most of the rest were nonprofit.27 Meanwhile, most LTCI nursing homes, whose services are nearly fully covered, are managed by nonprofit social welfare corporations.

Family care leave benefits (part of employment insurance) are paid for up to 93 days when employees take leave to care for family members with long-term care needs. A portion of long-term care expenses can be deducted from taxable income.

What are the major strategies to ensure quality of care?

By law, prefectures are responsible for making health care delivery “visions,” which include detailed service plans for treating cancer, stroke, acute myocardial infarction, diabetes mellitus, and psychiatric disease. These delivery visions also include plans for developing pediatric care, home care, emergency care, prenatal care, rural care, and disaster medicine. Structural, process, and outcome indicators are identified, as well as strategies for effective and high-quality delivery. Prefectures promote collaboration among providers to achieve these plans, with or without subsidies as financial incentives.

Prefectures are in charge of the annual inspection of hospitals. Penalties include reduced reimbursement rates if staffing per bed falls below a certain ratio. Hospital accreditation is voluntary. As of 2016, 26 percent of hospitals were accredited by the Japan Council for Quality Health Care, a nonprofit organization.28 The names of hospitals that fail the accreditation process are not disclosed.

Public reporting on the performance of hospitals and nursing homes is not obligatory, but the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare organizes and financially promotes a voluntary benchmarking project in which hospitals report quality indicators on their websites. National and local government facilitate mandatory third-party evaluations of welfare institutions, including nursing homes and group homes for people with dementia, to improve care.

To practice, physicians are required to obtain a license by passing a national exam. Although physicians are not subject to revalidation, specialist societies have introduced revalidation for qualified specialists. Some physician fees are paid on the condition that physicians have completed continuing medical education credits. Public reporting on physician performance is voluntary.

Every prefecture has a Medical Safety Support Center for handling complaints and promoting safety. Since 2004, advanced treatment hospitals have been required to report adverse events to the Japan Council for Quality Health Care. The council works to improve quality throughout the health system and develops clinical guidelines, although it does not have any regulatory power to penalize poorly performing providers.

The Japanese Medical Specialty Board, a physician-led nonprofit body, established a new framework for standards and requirements of medical specialty certification; it was implemented in 2018.

The government promotes the development of disease and medical device registries, mostly for research and development.

Surveys of inpatients’ and outpatients’ experiences are conducted and publicly reported every three years. Nonprofit organizations work toward public engagement and patient advocacy, and every prefecture establishes a health care council to discuss the local health care plan. Under the Medical Care Law, these councils must have members representing patients.

What is being done to reduce disparities?

Reducing health disparities between population groups has been a goal of Japan’s national health promotion strategy since 2012. The strategy sets two objectives: the reduction of disparities in healthy life expectancies between prefectures and an increase in the number of local governments organizing activities to reduce health disparities.29

Health disparities between regions are regularly reported by the national government; disparities between socioeconomic groups and in health care access have been occasionally measured and reported by researchers.

What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?

The national government prioritizes care coordination and develops financial incentives to encourage providers to coordinate care across care settings, particularly in cancer, stroke, cardiac care, and palliative care. For example, hospitals admitting stroke victims or patients with hip fractures can receive additional fees if they use post-discharge protocols and have contracts with clinic physicians to provide effective follow-up care after discharge. The clinic physicians also receive additional fees.

The government also provides subsidies to leading providers in the community to facilitate care coordination. Highly specialized, large-scale hospitals with 500 beds or more have an obligation to promote care coordination among providers in the community; meanwhile, they are obliged to charge additional fees to patients who have no referral for outpatient consultations.

There are more than 4,000 community comprehensive support centers that coordinate services, particularly for those with long-term conditions.30 Funded by LTCI, they employ care managers, social workers, and long-term care support specialists. Currently, there is no pooled funding between the SHIS and LTCI.

Regional and large-city governments are required to establish councils to promote integration of care and support for patients with 306 designated long-term diseases.

In addition, the national government has been promoting the idea of selecting preferred physicians. The Continuous Care Fees program pays physicians monthly payments for providing continuous care (including referrals to other providers, if necessary) to outpatients with chronic disease. The 2018 revision of the SHIS fee schedule ensures that physicians in this program receive a generous additional initial fee for their first consultation with a new patient.31

What is the status of electronic health records?

Electronic health record networks have been developed only as experiments in selected areas. Interoperability between providers has not been generally established. The government has been addressing technical and legal issues prior to establishing a national health care information network so that health records can be continuously shared by patients, physicians, and researchers by 2020.32 Unique patient identifiers for health care are to be developed and linked to the Social Security and Tax Number System, which holds unique identifiers for taxation.

How are costs contained?

The 30 percent coinsurance in the SHIS does not appear to work well for containing costs. By contrast, price regulation for all services and prescribed drugs seems a critical cost-containment mechanism. The fee schedule is revised every other year by the national government, following formal and informal stakeholder negotiations. The revision involves three levels of decision-making:

- the overall rate of increase or decrease in prices of all benefits covered by SHIH

- revised prices for drugs and devices

- prices of individual services.33

For medical, dental, and pharmacy services, the Central Social Insurance Medical Council revises provider service fees on an item-by-item basis to meet overall spending targets set by the cabinet. Highly profitable categories usually see larger reductions.

Price revisions for pharmaceuticals and medical devices are determined based on a market survey of actual current prices (which are usually less than the listed prices). Drug prices can be revised downward for new drugs selling in greater volume than expected and for brand-name drugs when generic equivalents hit the market. Prices of generic drugs have gradually decreased. Prices of medical devices in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Australia are also considered in the revision.

The fee schedule includes financial incentives to improve clinical decision-making. For example, if a physician prescribes more than six drugs to a patient on a regular basis, the physician receives a reduced fee for writing the prescription. Insurers’ peer-review committees monitor claims and may deny payment for services deemed inappropriate.

Prefectures regulate the number of hospital beds using national guidelines. The number of medical students is also regulated (see “Physician education and workforce” above).

The national Cost-Containment Plan for Health Care, introduced in 2008 and revised every five years, is intended to control costs by promoting healthy behaviors, shortening hospital stays through care coordination and home care development, and promoting the efficient use of pharmaceuticals. Prefectures also set health expenditure targets with planned policy measures, in accordance with national guidelines.

What major innovations and reforms have recently been introduced?

The Social Security Council set the following four objectives for the 2018 fee schedule revision:

- developing efficient and comprehensive care in the community

- developing safe, reliable, high-quality care and creating services tailored to emerging needs

- reducing the workload of health care workers

- making the health care system more efficient and sustainable.34

To proceed with these policy objectives, the government modified numerous incentives in the fee schedule. In addition to the Continuous Care Fees (see “What is being done to promote delivery system integration and care coordination?” above), hospital payments are now more differentiated, according to hospitals’ staff density, than those of the previous schedule.

The author would like to acknowledge David Squires as a contributing author to earlier versions of this profile.