Abstract

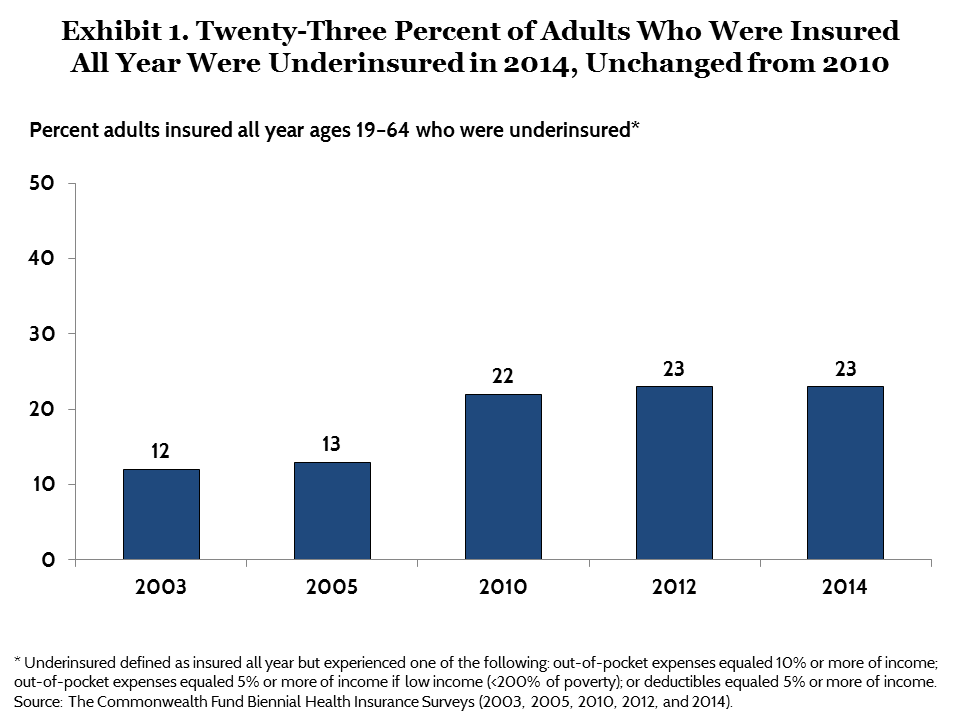

New estimates from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2014, indicate that 23 percent of 19-to-64-year-old adults who were insured all year—or 31 million people—had such high out-of-pocket costs or deductibles relative to their incomes that they were underinsured. These estimates are statistically unchanged from 2010 and 2012, but nearly double those found in 2003 when the measure was first introduced in the survey. The share of continuously insured adults with high deductibles has tripled, rising from 3 percent in 2003 to 11 percent in 2014. Half (51%) of underinsured adults reported problems with medical bills or debt and more than two of five (44%) reported not getting needed care because of cost. Among adults who were paying off medical bills, half of underinsured adults and 41 percent of privately insured adults with high deductibles had debt loads of $4,000 or more.

BACKGROUND

The Affordable Care Act has transformed the health insurance options available to Americans who lack health benefits through a job. Numerous surveys have indicated that the law’s coverage expansions and protections have reduced the number of uninsured adults by as many as 17 million people.1

But Congress intended the Affordable Care Act to do more than expand access to insurance; it intended for the new coverage to allow people to get needed health care at an affordable cost. Accordingly, for marketplace plans, the law includes requirements like an essential health benefit package, cost-sharing subsidies for lower-income families, and out-of-pocket cost limits.2 For people covered by Medicaid, there is little or no cost-sharing in most states.

But most Americans—more than 150 million people—get their health insurance through employers.3 Prior to the Affordable Care Act, employer coverage was generally far more comprehensive than individual market coverage.4 However, premium cost pressures over the past decade have led companies to share increasing amounts of their health costs with workers, particularly in the form of higher deductibles.5

In this issue brief, we use a measure of “underinsurance” from the Commonwealth Fund’s Biennial Health Insurance Survey to examine trends from 2003 to 2014, focusing on how well health insurance protects people from medical costs. Adults in the survey are defined as underinsured if they had health insurance continuously for the proceeding 12 months but still had out-of-pocket costs or deductibles that were high relative to their incomes (see Box #1). The survey was fielded between July and December 2014. This means that we could not separately assess the effects of the Affordable Care Act on underinsurance because people who were insured all year in the survey had insurance that began before the law’s major coverage expansions and reforms went into effect. People who had new marketplace or Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act would not have had that coverage for a full 12 months, as it would have begun in January 2014 at the earliest. Similarly, people with individual market coverage who were insured all year would have spent all or part of the period in plans that did not yet reflect the consumer protections in the law.6

| BOX #1. WHO IS UNDERINSURED?

In this analysis, we use a measure of underinsurance that takes into account an insured adult’s reported out-of-pocket costs over the course of a year, not including premiums, and the health plan deductible. The measure was developed by Cathy Schoen and first used in The Commonwealth Fund’s 2003 Biennial Health Insurance Survey. These actual expenditures and the potential risk of expenditures, as represented by the deductible, are then compared with household income. Specifically, someone who is insured all year is underinsured if:

The out-of-pocket cost component of the measure is only triggered if a person uses his or her plan. The deductible component provides an indicator of the financial protection the plan offers and the risk of incurring costs even before a person uses the plan. The definition does not include people who are at risk of incurring high costs because of other design elements, such as exclusion of certain covered benefits and copayments. It therefore provides a conservative measure of underinsurance in the United States. |

SURVEY FINDINGS

An Estimated 31 Million Adults Are Underinsured, Unchanged from 2010

As of July 2014 through December 2014, 23 percent of U.S. adults ages 19 to 64 who were insured all year, or an estimated 31 million people, were underinsured (Exhibit 1, Table 1). This is nearly double the number of underinsured adults in 2003 when the measure was first introduced in the survey, but it is statistically unchanged compared with 2010 and 2012.7

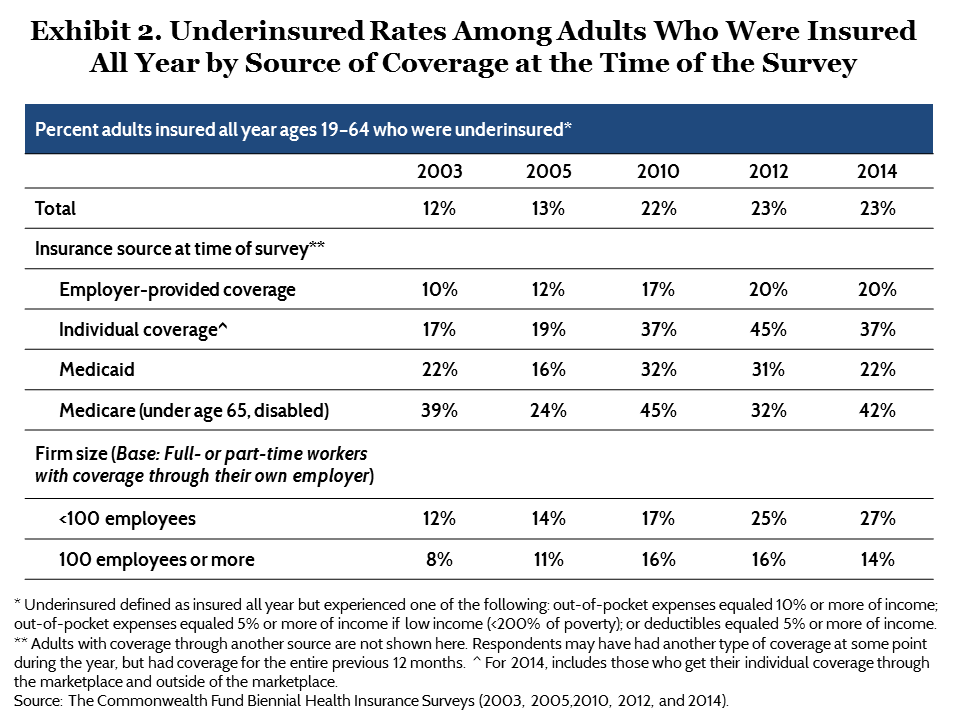

Underinsured rates by source of coverage. The national underinsured estimates are dominated by people in employer plans: 59 percent of underinsured adults had coverage through employers at the time of the survey (Table 2).8 Because of the timing of the survey, people with marketplace plans who were insured all year would have had a different source of insurance for part of that time.9 In addition, sample sizes were small. For these reasons, we grouped adults with marketplace plans and adults with individual market plans together.

The share of adults who were underinsured climbed over time in each coverage group but increases leveled off after 2012. Among adults who were insured all year and had employer-based coverage at the time of the survey, the percentage underinsured climbed from 10 percent in 2003 to 20 percent in 2012, but remained at 20 percent in 2014 (Exhibit 2). Rates were highest among adults working in small firms. Among adults with health benefits through their own employer who were working part-time or full-time in companies with fewer than 100 workers, 27 percent were underinsured in 2014 compared with 14 percent of those working in companies with 100 or more employees.

The percentage of adults with individual market policies at the time of the survey who were underinsured rose from 17 percent in 2003 to 45 percent in 2012, and then declined slightly to 37 percent in 2014. The decline in 2014 was not statistically significant.

About one of five (22%) adults with Medicaid coverage were underinsured in 2014, down from 31 percent in 2012. Adults in this group are the poorest in the survey. Medicaid requires little cost-sharing, but because people eligible for the program have very low incomes, minor out-of-pocket costs can comprise a large share of income.

Underinsured rates were highest among adults under age 65 with Medicare. This is by far the sickest group of covered adults in the survey—91 percent are disabled or in fair or poor health—and the second-poorest after Medicaid enrollees (data not shown).10 Many have very high health expenditures and low incomes. Consequently, more than two of five (42%) adults in this group were underinsured in 2014.

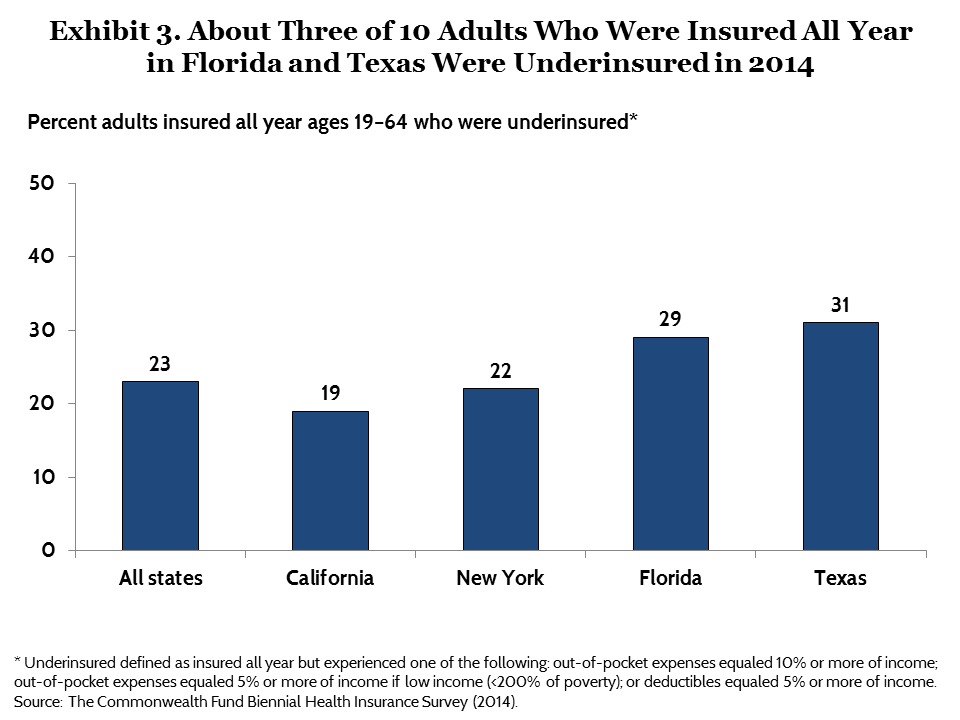

Underinsured rates in the four largest states. The survey drew additional samples of people in the nation’s four largest states to enable analysis of people’s experiences in those states.11 Adults in Florida and Texas were underinsured at higher rates than those in California and New York. Among adults who were insured all year, 29 percent of Floridians and 31 percent of Texans were undersinsured compared with 19 percent of Californians and 22 percent of New Yorkers (Exhibit 3, Table 3).

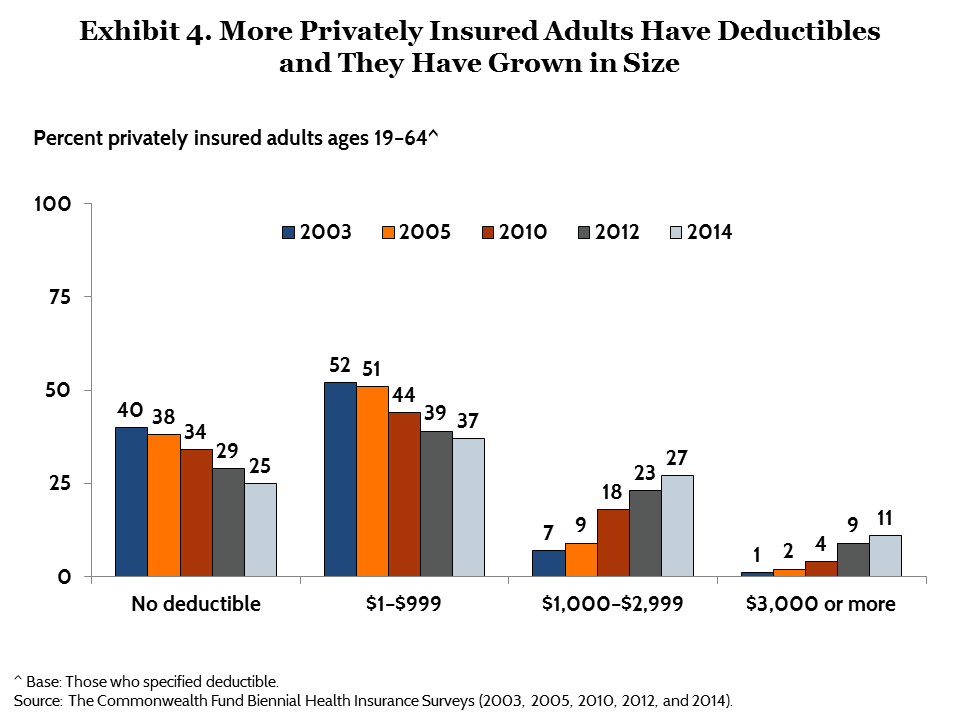

Deductibles Are a Growing Cause of Underinsurance

Between 2003 and 2014, deductibles were increasingly a factor in underinsurance because more insured people than ever before have health plans with deductibles and more people have deductibles that are high relative to their incomes. The share of privately insured adults who had a health plan without a deductible fell from 40 percent in 2003 to 25 percent in 2014 (Exhibit 4, Table 4). At the same time, deductibles grew in size. By 2014, more than one of 10 (11%) adults enrolled in a private plan had a deductible of $3,000 or more, up from just 1 percent in 2003.

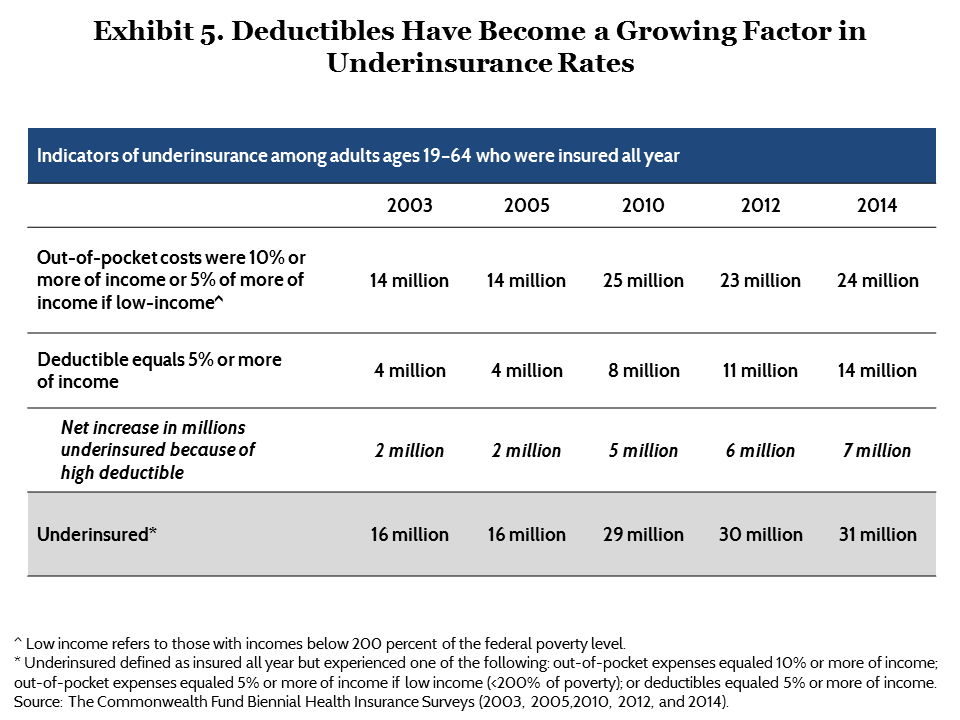

Deductibles are outpacing growth in many families’ incomes, and thus representing a greater share of that income.12 In 2014, 11 percent of adults with insurance coverage all year, or 14 million people, had a deductible that was high relative to their their income, up from 3 percent, or 4 million people, in 2003 (Exhibit 5, Table 1).

The effect of these trends on the underinsured rate has been substantial. In 2014, an estimated 7 million people were underinsured because of their deductible alone. This is an increase from 2 million in 2003.

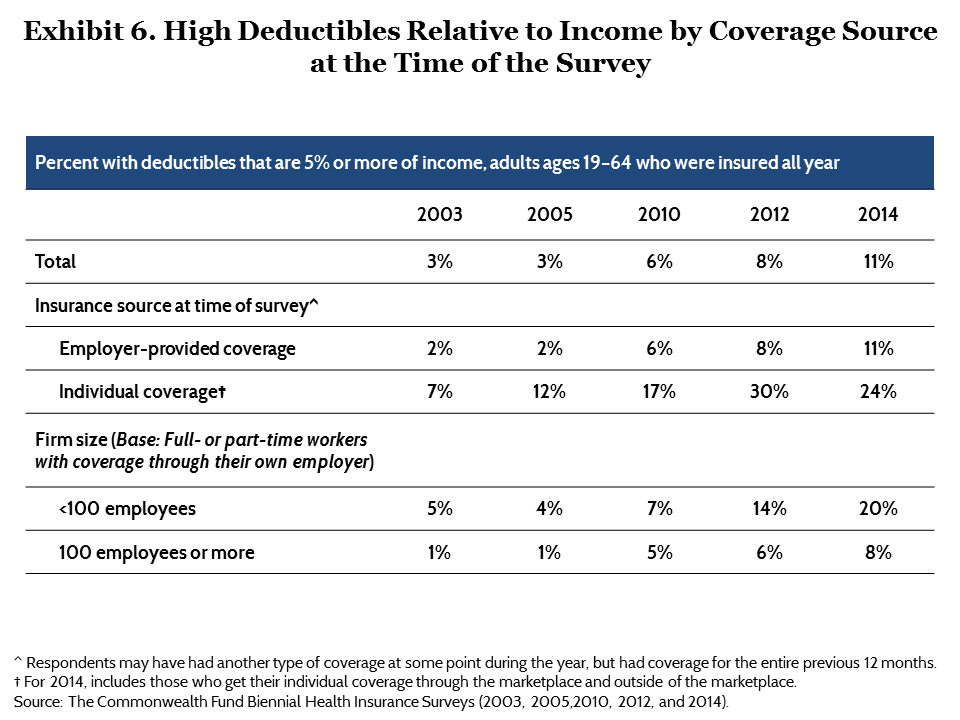

High deductibles by coverage source. Among people who had health insurance all year and employer coverage at the time of the survey, the share with a deductible that was high relative to income grew from 2 percent in 2003 to 11 percent in 2014 (Exhibit 6). Rates were highest among workers in small firms. Among adults with health benefits through their own employer who were working part-time or full-time in companies with fewer than 100 workers, 20 percent had high deductibles relative to income compared with 8 percent of those working in companies of 100 or more employees.

The percentage of adults with individual market policies at the time of the survey who had high deductibles as a share of income rose from 7 percent in 2003 to 30 percent in 2012, and declined slightly to 24 percent in 2014. The decline in 2014 was not statistically significant.

High deductibles in the four largest states. The share of insured adults in Florida and Texas with high deductibles relative to income exceeded the national average at 12 percent and 15 percent, respectively. California and New York had considerably lower shares at 6 percent (Table 3).13

Adults with Low Incomes or Health Problems Are at Greatest Risk of Underinsurance

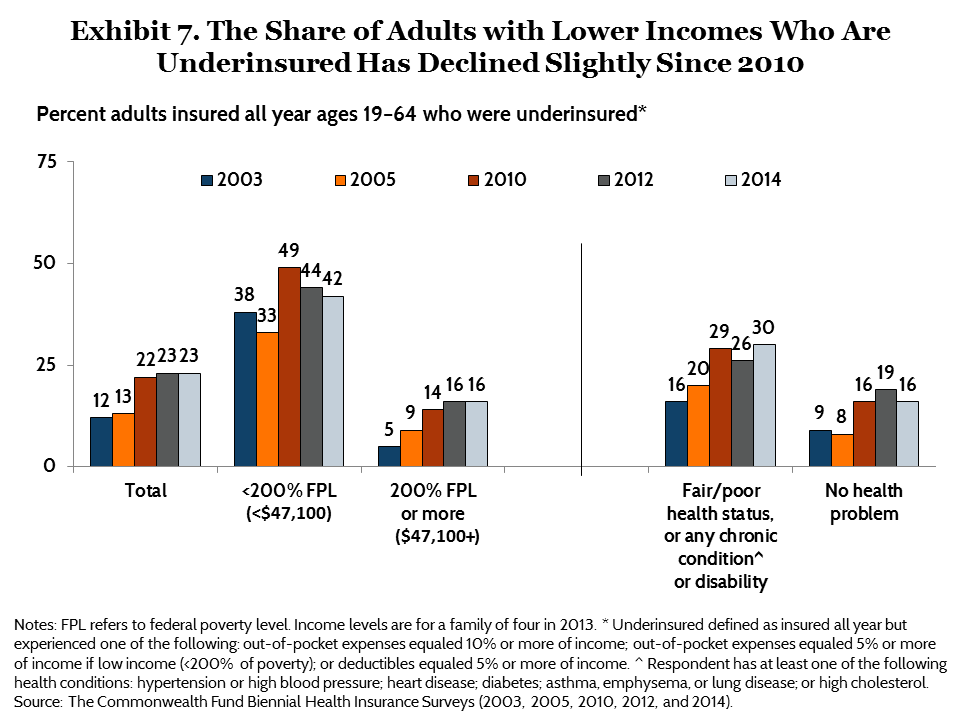

Since 2010, there has been some improvement in the share of low-income people who are underinsured. Among adults who had health insurance for the full year, 42 percent of those with incomes under 200 percent of the federal poverty level ($22,980 for an individual and $47,100 for a family of four) were underinsured in 2014, down slightly but significantly from 2010 (Exhibit 7). The decline occurred primarily among people in that income range who had coverage through Medicaid at the time of the survey (data not shown). There was no significant improvement among adults in that income range with insurance through an employer.

Despite the decline, people with lower incomes were underinsured at more than two times the rate of people with higher incomes. Indeed, people with low incomes comprise 61 percent of underinsured adults in the United States (Table 2).

People who have health problems are also at greater risk of being underinsured since they generally have higher health care costs than healthier people. Among adults who were insured all year, 30 percent of those in fair or poor health or who have a chronic health problem or disability were underinsured compared with 16 percent of those who were healthier.

Adults Who Are Underinsured Have High Rates of Medical Bill Problems

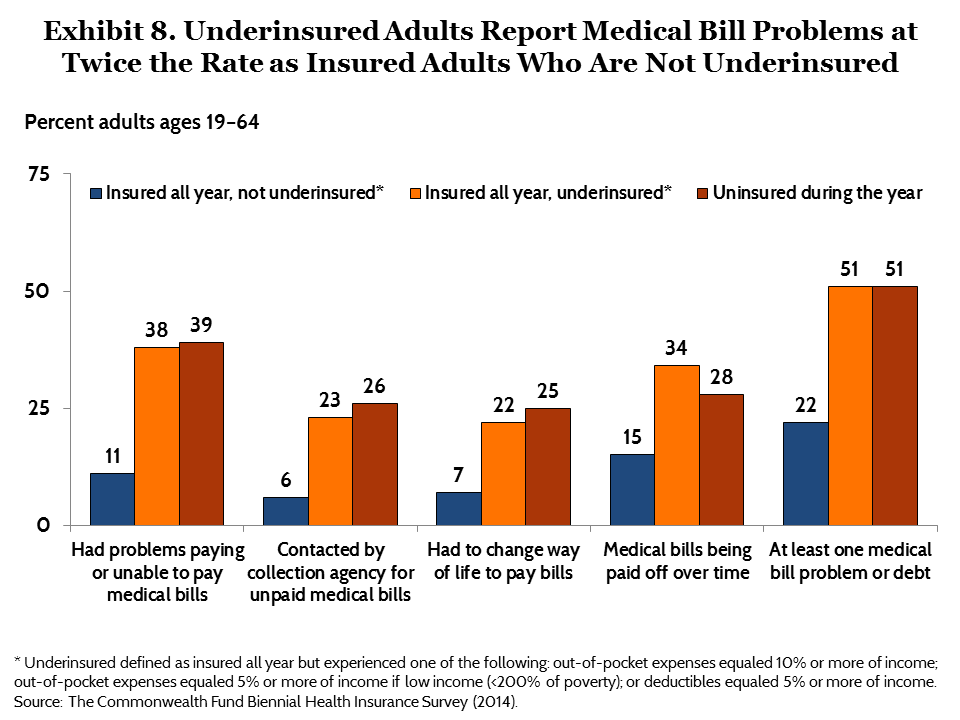

Greater cost exposure is leaving Americans burdened with medical debt. Half (51%) of underinsured adults reported problems paying their medical bills or said they were paying off medical debt. This is the same rate as adults who were uninsured during the year and more than twice the rate reported by insured adults who were not underinsured (22%) (Exhibit 8, Table 5).

Among adults with private coverage who had been insured all year, those with high deductibles were more likely to report problems with medical bills than those with low or no deductibles. More than two of five (41%) adults with a deductible of $3,000 or more said they had difficulty paying their medical bills or had accumulated medical debt compared with 13 percent of those who did not have a deductible (Table 5).

Among adults who were paying off medical bills over time, those who were underinsured or had high deductibles were carrying the largest debt loads. Half of underinsured adults and 41 percent of privately insured adults with deductibles of $1,000 or higher were paying off accumulated medical bills of $4,000 or more (Table 5).

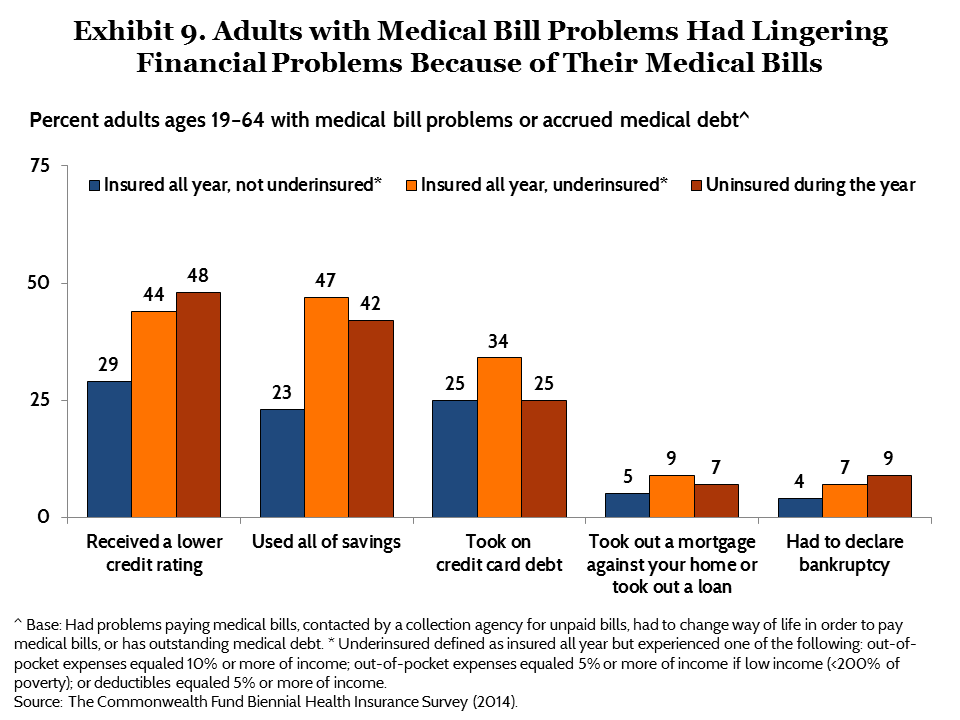

Medical Bill and Debt Problems Have Long-Term Financial Consequences

Many adults who have struggled to pay their medical bills report lingering financial problems as a result. People who are underinsured and those who are uninsured have the highest rates of such problems: both groups had higher debt loads and lower incomes than adults who were insured but not underinsured (data not shown). Nearly half (47%) of underinsured adults who had problems paying medical bills or had medical debt said they had used up all their savings to pay their bills and 44 percent said they had received a lower credit rating because of their bills (Exhibit 9, Table 5). One-third (34%) of underinsured adults with medical bill problems said they had taken on credit card debt to pay bills. About 7 percent of underinsured adults reported that they had to declare bankruptcy because of medical bills.

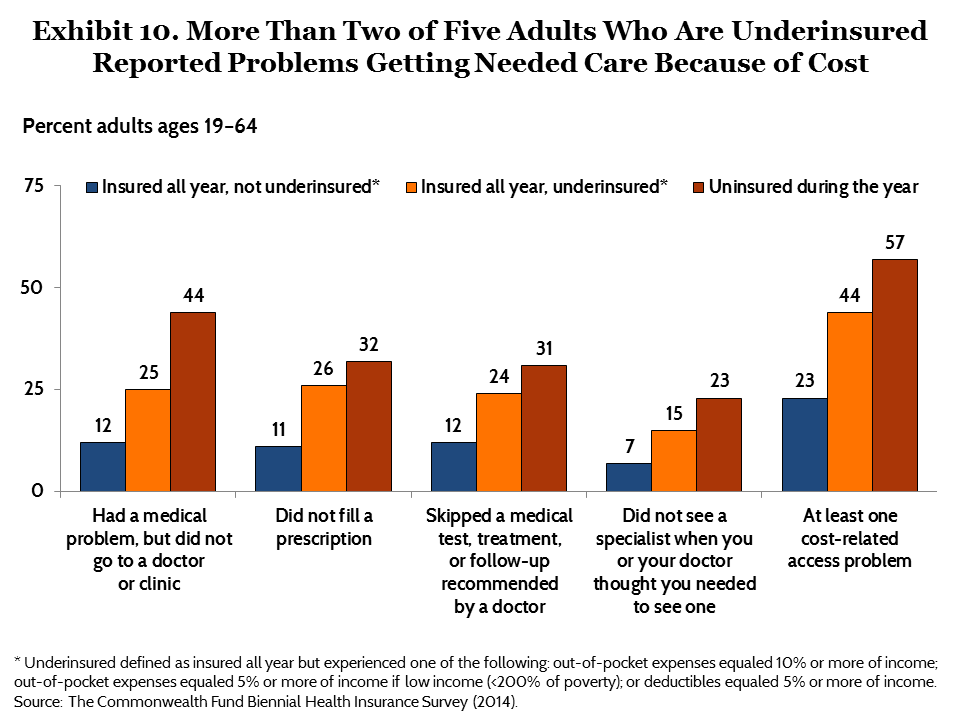

Underinsured Adults Report Not Getting Needed Care Because of Cost

Underinsured adults are more likely to skip needed health care because of cost than adults with more cost-protective insurance. More than two of five (44%) underinsured adults reported not getting needed care because of cost in the past year, including not going to the doctor when sick, not filling a prescription, skipping a test or treatment recommended by a doctor, or not seeing a specialist (Exhibit 10, Table 6). This is almost twice the rate of continuously insured adults who were not underinsured (23%). But people who had been uninsured during the year reported avoiding needed care because of cost at the highest rates (57%).

Privately insured adults with coverage all year who had health plans with high deductibles were more likely than those with low or no deductibles to report cost-related problems getting health care. More than two of five (44%) privately insured adults with a deductible of $3,000 or more reported not getting needed care because of cost compared with 16 percent of adults who did not have a deductible (Table 6).

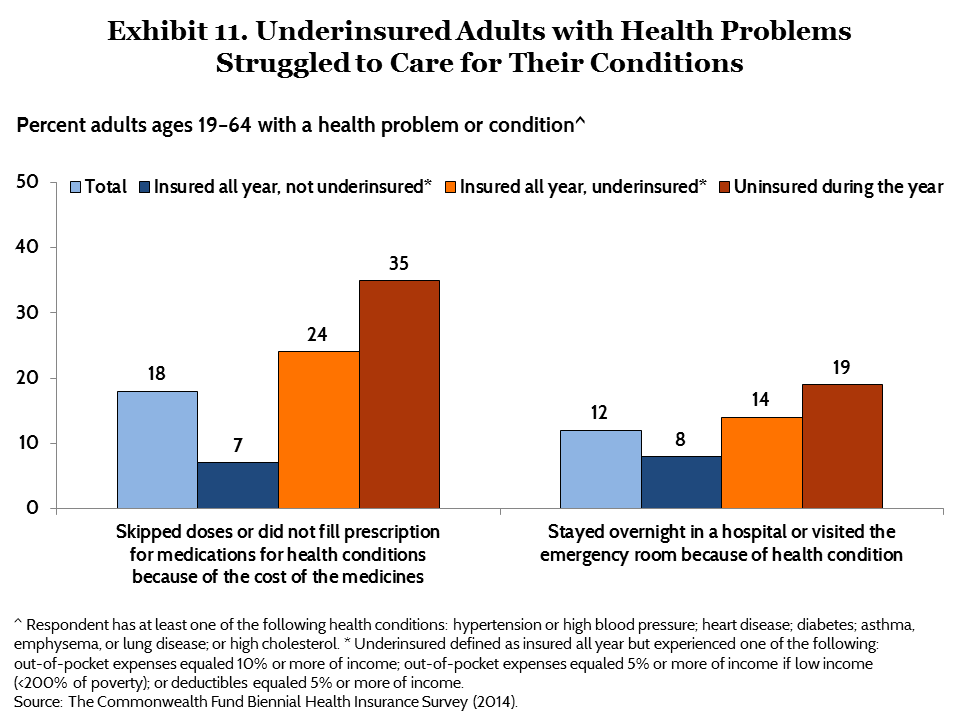

Many underinsured adults with health problems reported difficulty caring for their conditions. Among adults with at least one chronic health condition, a quarter (24%) of those who were underinsured said they had not filled a prescription for their condition or had skipped a dose of their medication because of cost, compared with 7 percent of those insured all year and not underinsured (Exhibit 11).14 Similarly, underinsured adults with chronic health conditions were more likely to say they had gone to the emergency room or stayed overnight in the hospital for their condition than were insured adults with health problems who were not underinsured.

CONCLUSION

The rate of growth in medical costs and insurance premiums has slowed in recent years. However, millions of consumers continue to be saddled with high out-of-pocket health care costs. While the number of underinsured people in the United States held constant in 2014, the steady growth in the proliferation and size of deductibles threatens to increase underinsurance in the years ahead.

The Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansions and protections have greatly improved the quality of insurance coverage available to people who lack job-based health benefits. In addition, cost-sharing subsidies significantly reduce deductibles for people with low incomes who buy plans in the marketplaces. But those subsidies phase out quickly, leaving families with deductibles that may be high relative to their incomes. In addition, the law has only limited ability to improve the cost protection of employer plans, which is the source of most American’s health insurance.

Reforms and new approaches are needed to improve the cost protection of health plans. These could include innovations in benefit design that slow growth in deductibles and emphasize incentives that encourage people to utilize, rather than delay, timely health care. In addition, policymakers should identify and address holes in health plans—like out-of-network physicians in in-network hospitals—which are surprising many families with unexpected costs. Finally, systemwide efforts to lower the underlying rate of medical cost growth and share those savings with consumers will be critical.

MethodologyThe Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey, 2014, was conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International from July 22 to December 14, 2014. The survey consisted of 25-minute telephone interviews in either English or Spanish and was conducted among a random, nationally representative sample of 6,027 adults ages 19 and older living in the continental United States. A combination of landline and cellular phone random-digit dial samples was used to reach people. In all, 3,002 interviews were conducted with respondents on landline telephones and 3,025 interviews were conducted on cellular phones, including 1,799 with respondents who live in households with no landline telephone access. An oversample of the four largest states, California, Florida, New York, and Texas, was collected until December 27, 2014. The sample was designed to generalize to the U.S. adult population and to allow separate analyses of responses of low-income households. This report limits the analysis to respondents ages 19 to 64 (n=4,251), and much of the report focuses on adults who have been insured all year (n=3,032). Statistical results are weighted to correct for the stratified sample design, the overlapping landline and cellular phone sample frames, and disproportionate nonresponse that might bias results. The data are weighted to the U.S. adult population by age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, household size, geographic region, population density, and household telephone use, using the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. The resulting weighted sample is representative of the approximately 182.8 million U.S. adults ages 19 to 64. The survey has an overall margin of sampling error of +/– 2 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level. The landline portion of the survey achieved a 15.8 percent response rate and the cellular phone component achieved a 13.6 percent response rate. We also report estimates from the 2003, 2005, 2010, and 2012 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Surveys. These surveys were conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International using the same stratified sampling strategy that was used in 2014, except the 2003 and 2005 surveys did not include a cellular phone random-digit dial sample. In 2003, the survey was conducted from September 3, 2003, through January 4, 2004, and included 3,293 adults ages 19 to 64; in 2005, the survey was conducted from August 18, 2005, to January 5, 2006, among 3,352 adults ages 19 to 64; in 2010, the survey was conducted from July 14 to November 30, 2010, among 3,033 adults ages 19 to 64; and in 2012, the survey was conducted from April 26 to August 19, 2012, among 3,393 adults ages 19 to 64. |

Notes

1 K. G. Carman, C. Eibner and S. M. Paddock, “Trends in Health Insurance Enrollment, 2013–15,” Health Affairs, published online May 2015; S. K. Long, M. Karpman, G. M. Kenney et al., “Taking Stock: Gains in Health Insurance Coverage Under the ACA as of March 2015” (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, April 16, 2015); M. E. Martinez and R. A. Cohen, Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2014 (Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dec. 2014); S. R. Collins, P. W. Rasmussen, M. M. Doty, and S. Beutel, The Rise in Health Care Coverage and Affordability Since Health Reform Took Effect (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Jan. 2015); S. R. Collins, P. W. Rasmussen, and M. M. Doty, Gaining Ground: Americans’ Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care After the Affordable Care Act’s First Open Enrollment Period (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, July 2014); and R. Garfield and K. Young, Adults Who Remained Uninsured at the End of 2014 (Menlo Park, Calif.: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Jan. 2015).

2 With the exception of cost-sharing subsidies, these requirements also apply to health plans sold outside the marketplaces in the individual and small-group markets.

3 Congressional Budget Office, Updated Budget Projections: 2015–2025 (Washington, D.C.: CBO, March 2015).

4 The major insurance reforms in the Affordable Care Act are directed at the individual and small-group insurance markets where underwriting practices left many consumers and small businesses with poor health insurance coverage, or no coverage at all. But the law also extends some requirements to large employer-based plans, including coverage of preventive services without cost-sharing, limits on out-of-pocket costs, and bans on lifetime and annual benefit limits. Low- and moderate-income workers in health plans with high cost-sharing are eligible for subsidized coverage through the marketplaces. Those with incomes under 138 percent of poverty are eligible for Medicaid in states that have expanded eligibility for their programs.

5 C. Schoen, D. Radley, and S. R. Collins, State Trends in the Cost of Employer Health Insurance Coverage, 2003–2013 (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Jan. 2015).

6 In addition, many people with individual market coverage have been able to maintain plans that are not compliant with the law’s provisions under a policy introduced in the fall of 2013 by the Obama Administration. A consequence of a public outcry over noncompliant cancelled policies at a time that the marketplaces were not functioning well, the policy change is at the discretion of states and health plans and continues through 2017. See K. Lucia, S. Corlette, and A. Williams, "Some Health Insurers Canceling Noncompliant Policies, But Consumers Are More Informed of Coverage Options," The Commonwealth Fund Blog, Feb. 2, 2015.

7 All reported differences are statistically significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level or better unless otherwise noted.

8 This reflects the fact that most Americans have health insurance through an employer (see Table 2).

9 The survey asked people about how long they had their current health plan. More than eight of 10 adults (84%) with employer-based plans and about half (52%) of those with individual market plans had had the same health plan for more than one year (data not shown).

10 People under age 65 may become eligible for Medicare if they are disabled and are receiving Social Security Disability Insurance, or have been diagnosed with end stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

11 P. W. Rasmussen, S. R. Collins, M. M. Doty, and S. Beutel, Health Care Coverage and Access in the Nation’s Four Largest States (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, April 2015).

12 Schoen, Radley, and Collins, State Trends, 2003–2013, 2015.

13 An analysis of 2013 employer-based insurance found that average single-person deductibles were $1,194 in California, $1,112 in New York, $1,346 in Florida, and $1,543 in Texas, representing 3.8%, 3.4%, 4.5%, and 5.1% respectively as a share of median income in each state. See Schoen, Radley, and Collins, State Trends, 2003–2013, 2015.

14 Respondents had at least one of the following health conditions: hypertension or high blood pressure; heart disease; diabetes; asthma, emphysema, or lung disease; or high cholesterol.