Abstract

The latest Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey finds the share of uninsured working-age adults was 13 percent in March–May 2015, compared with 20 percent just before the major coverage expansions went into effect. More than half of adults who currently have coverage either through the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) marketplace plans or Medicaid expansion were uninsured prior to gaining coverage. Of those, more than 60 percent lacked coverage for one year or longer. More than six of 10 adults who used their new plans to obtain care reported they could not have afforded or accessed it previously. Majorities of people with ACA coverage who have used their plans express satisfaction with the doctors covered in their networks and are able to find physicians with relative ease. Wait times to get appointments with physicians in marketplace plans and Medicaid are comparable to those reported by other working-age adults.

Background

After the end of the Affordable Care Act’s second open enrollment period this spring, about 22 million people had enrolled in plans through the health insurance marketplaces or had newly enrolled in Medicaid.1 To examine the effect of this enrollment on uninsured rates and on people’s ability to access health care, the Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey interviewed a nationally representative sample of 19-to-64-year-old adults, including a sample of adults who either have marketplace or Medicaid coverage or might be eligible for it. The survey firm SSRS interviewed 4,881 adults by landline and cellphone from March 9 to May 3, 2015. These results are compared with two earlier waves of the survey conducted by SSRS. One was fielded in April to June 2014 at the end of the first open enrollment period and the other was conducted in July to September 2013, just before the first open enrollment period and the implementation of the law’s major coverage reforms.

Survey Findings

Thirteen Percent of U.S. Working-Age Adults Were Uninsured, March–May 2015

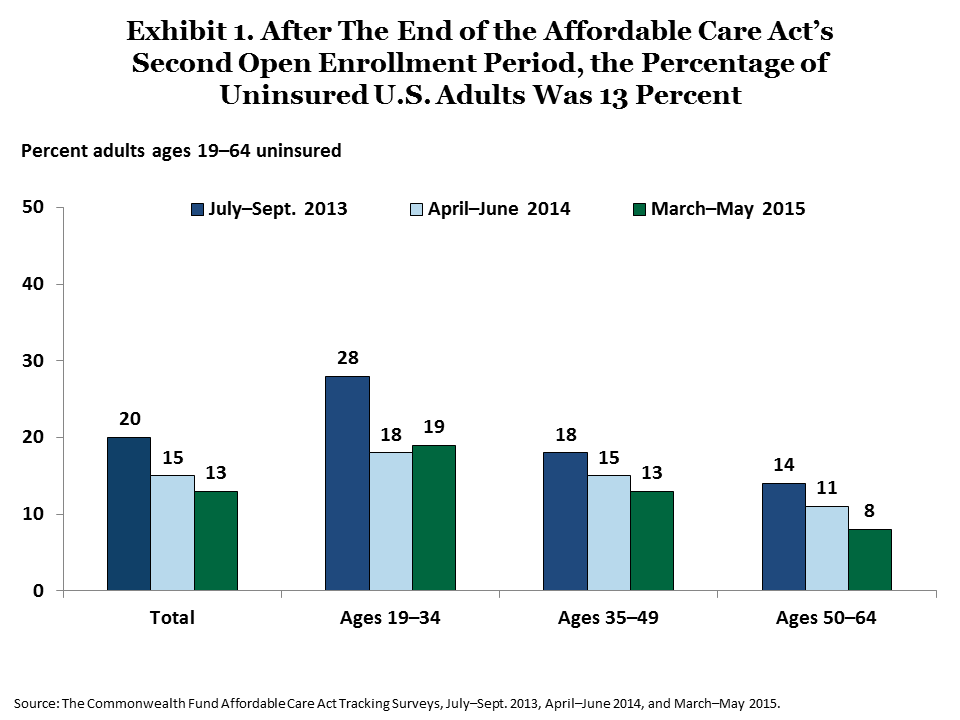

The survey finds that the number of adults who are uninsured is significantly below levels just prior to the major coverage reforms taking effect, but that gains were less in 2015.2 The percentage of adults ages 19 to 64 who are uninsured was 13 percent in March–May 2015, compared with 15 percent in April–June 2014, and 20 percent in July–September 2013, though the decline between 2014 and 2015 was not statistically significant (Exhibit 1).3 This represents an estimated decline of 12.1 million uninsured adults since the coverage expansions took effect.4 These changes are in the range of estimates reported by other recent surveys (Appendix).

There were differences in coverage gains in 2015 across age groups. While older adults continued to gain insurance in 2015, there were no significant changes in uninsured rates among adults under age 50 from the prior year. In March–May 2015, the share of adults ages 50 to 64 who lacked coverage declined to 8 percent from 11 percent in 2014. About 19 percent of young adults ages 19 to 34 and 13 percent of those ages 35 to 49 were uninsured in 2015, which are significantly below 2013 levels, but unchanged from 2014.

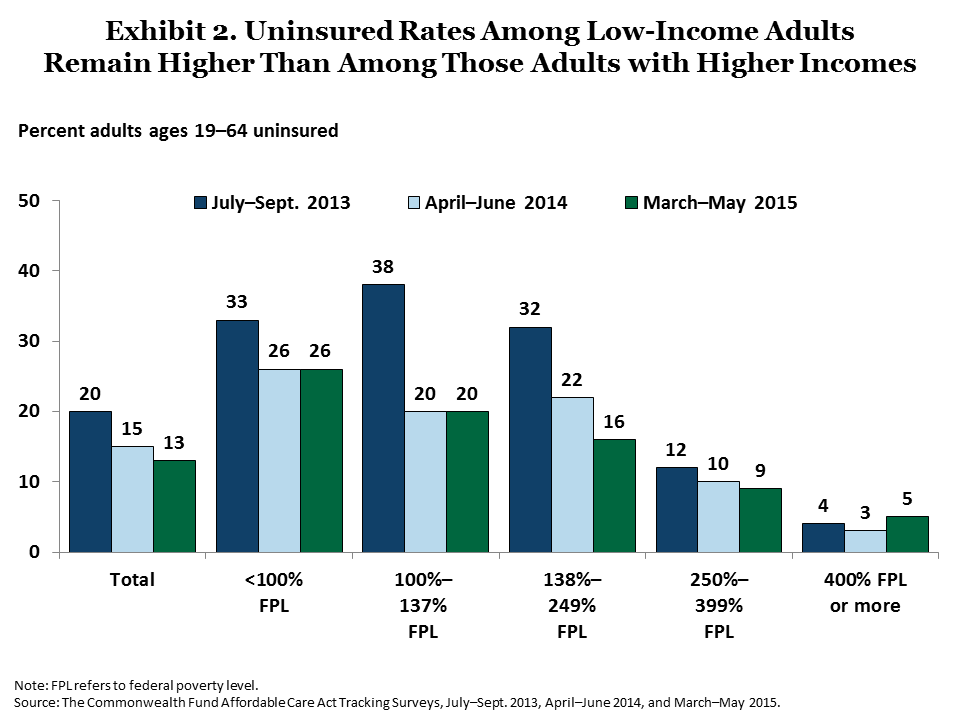

The coverage expansions are particularly targeted to help people with low and moderate incomes. These groups have made significant gains in coverage since the major expansions took effect (Exhibit 2). In the most recent survey, uninsured rates continued to fall among adults with incomes between 138 percent and 249 percent of poverty ($16,105 to $29,175 for an individual and $32,913 to $59,625 for a family of four). In contrast, the survey findings indicate no further declines in uninsured rates among people with incomes under 138 percent of poverty in 2015.

Coverage Expansions Are Ending Long Bouts of Uninsurance for Many Adults

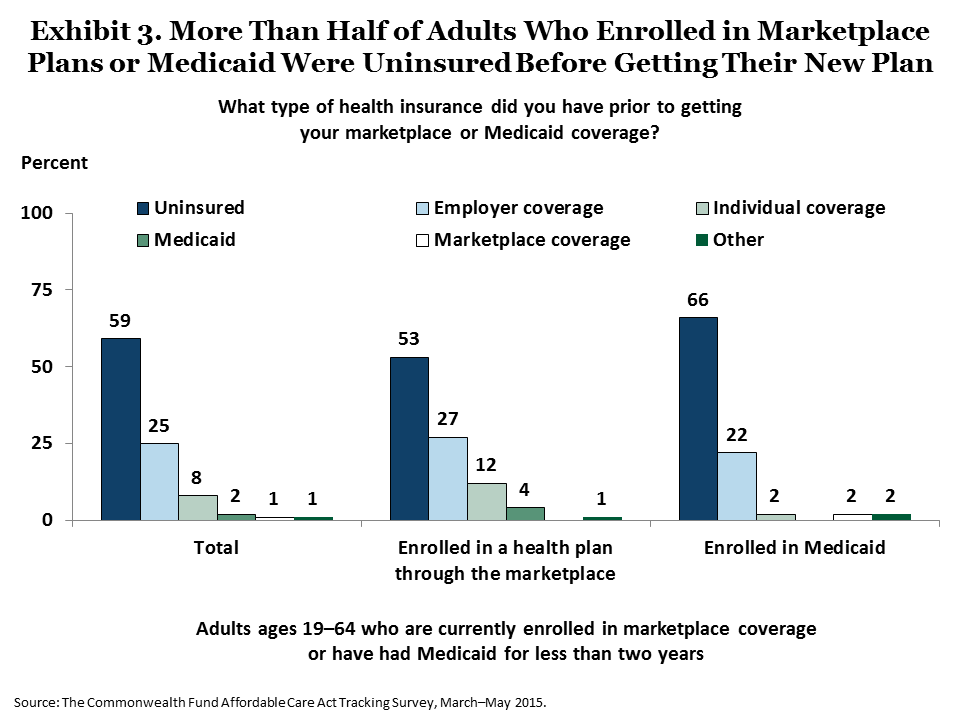

The survey finds that the law is fulfilling one of its main goals: helping uninsured people gain coverage. More than half (53%) of adults currently enrolled in marketplace plans and 66 percent enrolled in Medicaid were uninsured prior to gaining their new insurance (Exhibit 3).5

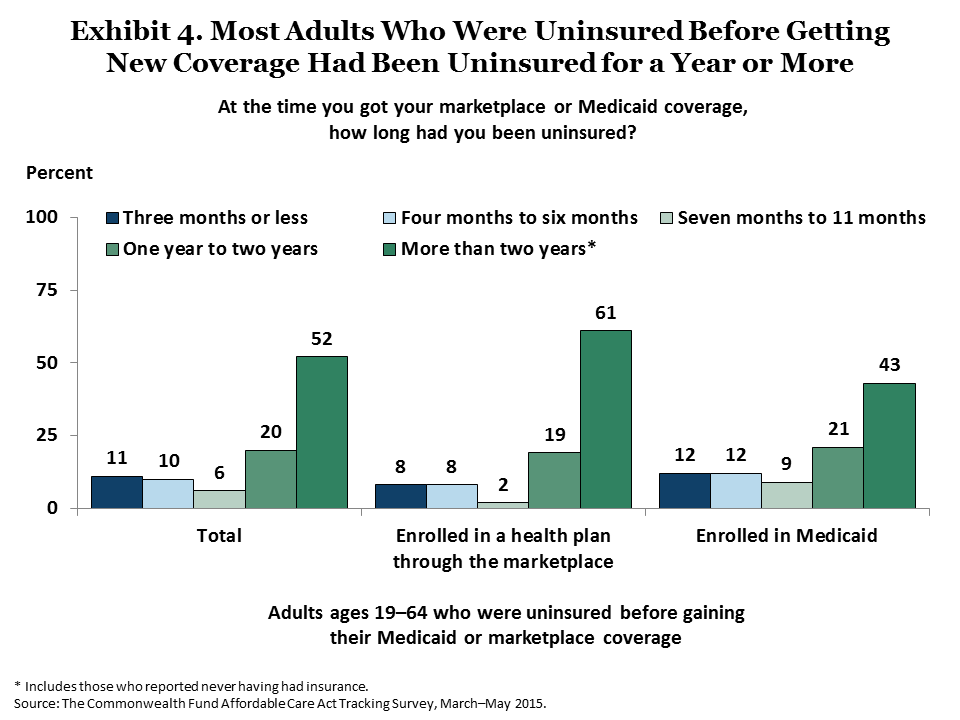

For many people, this new coverage ended lengthy periods without health insurance. Among adults who had been uninsured prior to gaining coverage, 80 percent of those enrolled in marketplace plans and 64 percent of those with Medicaid coverage had gone without insurance for a year or longer (Exhibit 4).

Coverage Expansions Are Improving People’s Access to Health Care

Earlier Commonwealth Fund surveys and other research have consistently found that people who lack health insurance are much less likely than those who have coverage to get the health care they need to stay healthy, manage their chronic conditions, or get well when they become sick or injured.6 Research also has found that people who are continuously insured but who have inadequate coverage face similar barriers to care.7 Thus, a key measure of the Affordable Care Act’s success is whether its new insurance options and reforms are improving Americans’ ability to get timely health care.

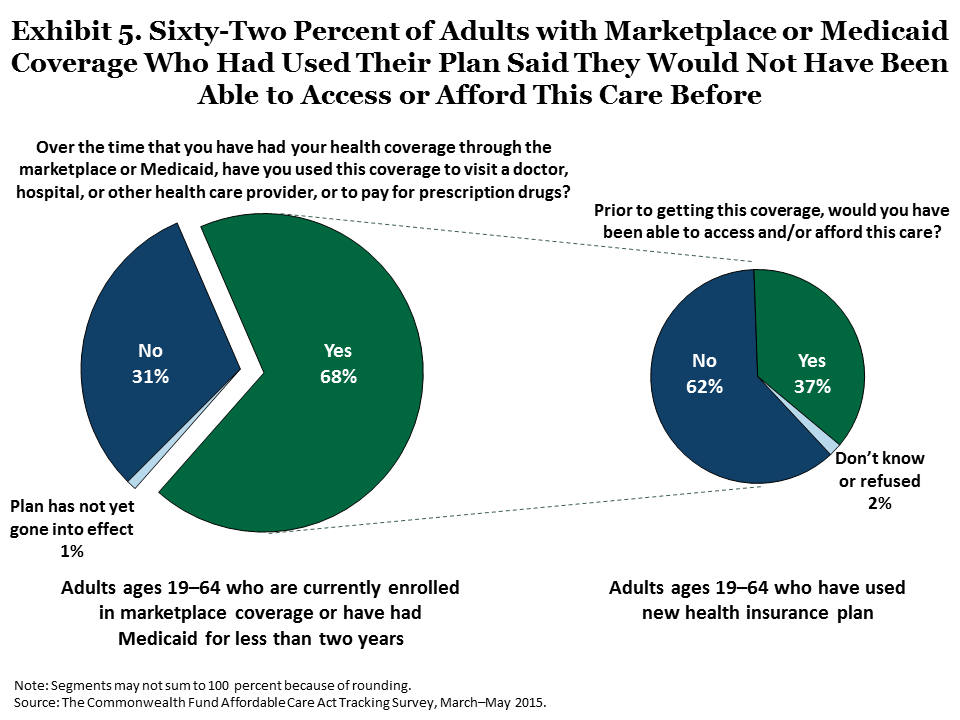

Survey evidence suggests ACA coverage is improving access. About 68 percent of adults currently enrolled in a marketplace plan or Medicaid sought care from a doctor or hospital or filled a prescription (Exhibit 5). Of those, 62 percent said they would not have been able to access or afford this care prior to getting their new insurance. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of people who were previously uninsured and had obtained care said they would not have been able to get this care prior to gaining insurance (Table 1).

The new coverage options have also improved access to care among those who previously had health insurance. Nearly half (47%) of adults who had insurance before enrolling in their plans and have since obtained care said they would not have been able to access or afford this care prior to getting their new plan.

Adults with New Coverage Are Finding Doctors and Getting Appointments

Since the ACA’s major coverage expansions went into effect, there has been concern about difficulty new enrollees might have finding doctors, getting timely appointments, and whether they would be satisfied with their choice of doctors.

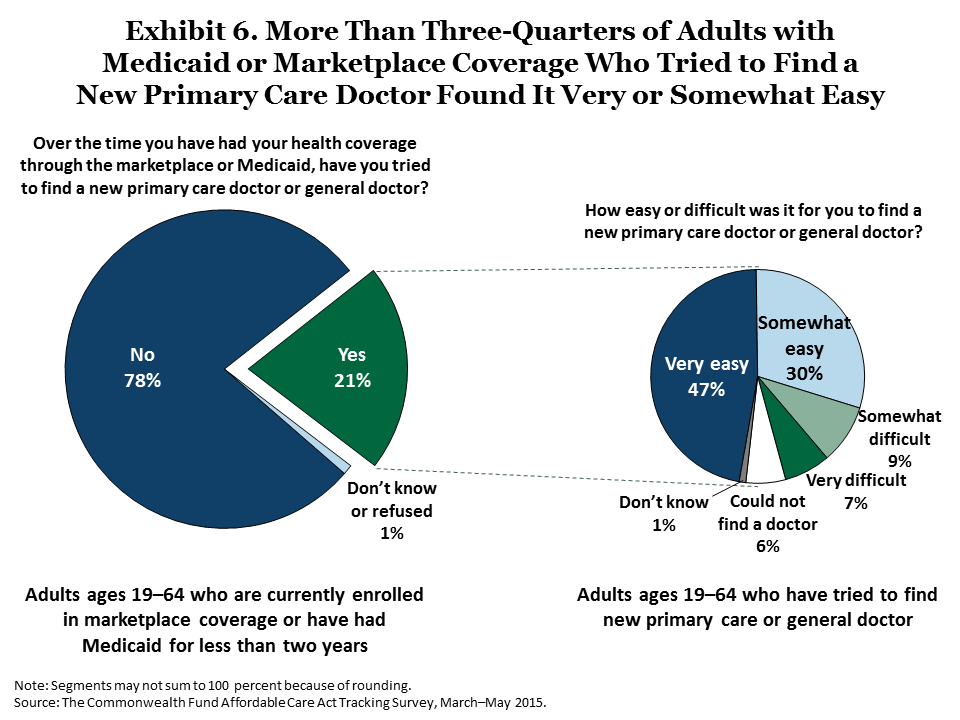

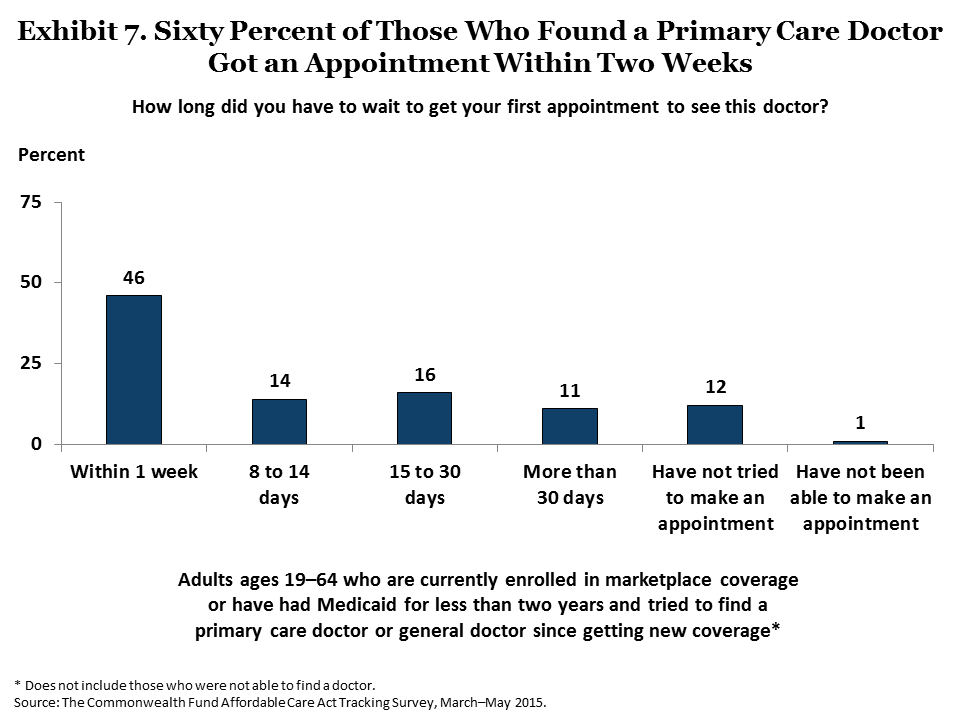

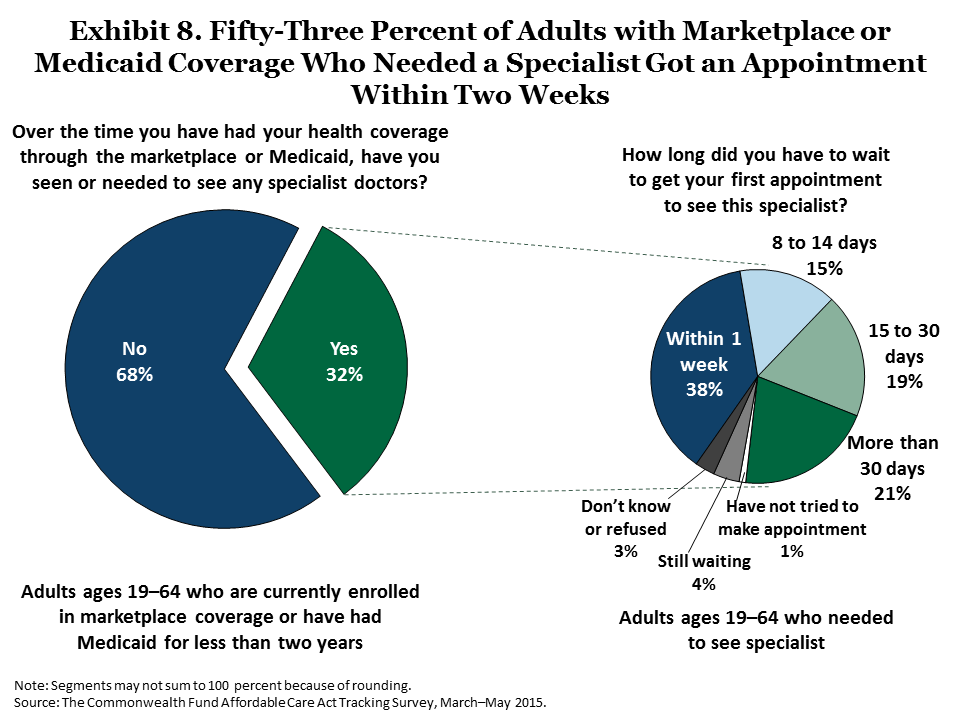

In the survey, a majority of respondents with either marketplace or Medicaid coverage who looked for new primary care doctors reported they found providers relatively easily and were able to secure appointments within a reasonable time frame (Exhibits 6 and 7).8 Sixty percent of those who found a new primary care doctor were able to get an appointment within two weeks, including 46 percent who got an appointment within one week. Similarly, among people who have needed to see a specialist, 53 percent were able to get their first appointment within two weeks, including 38 percent who were able to get an appointment within one week (Exhibit 8).

Some adults waited longer. About one of five (19%) adults who needed to see a specialist waited two weeks to one month; another 21 percent waited longer than one month. These wait times are similar to those reported in the 2014 ACA Tracking Survey9 and on average, are comparable to those that many Americans currently experience, as confirmed by other recent surveys of adults.10

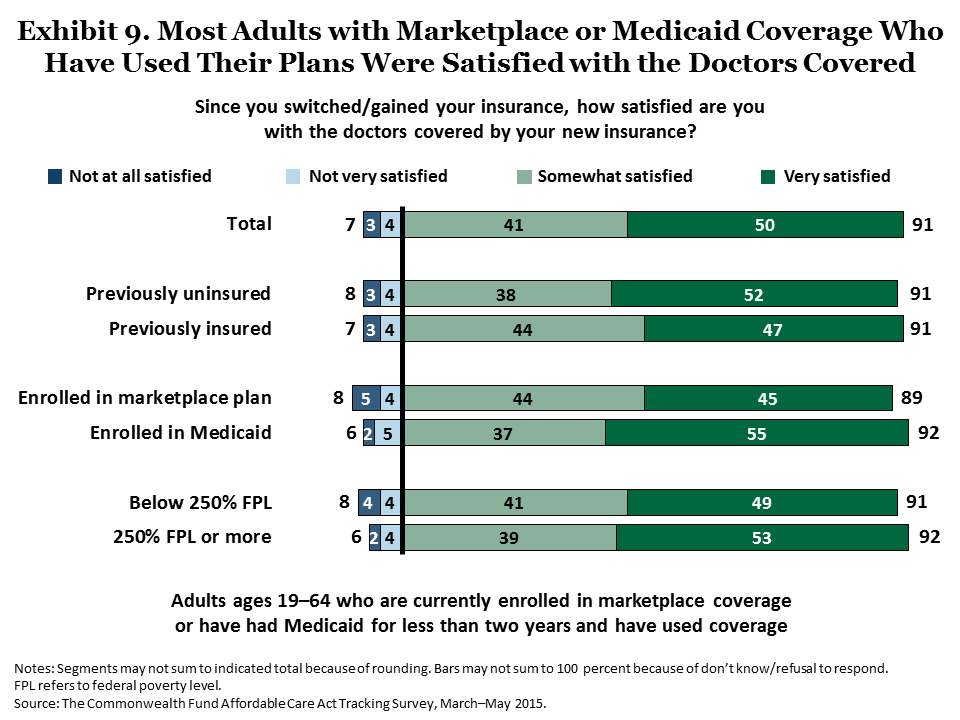

The survey also finds that majorities of people with new ACA coverage who have used their plans express satisfaction with the doctors covered in their networks. Among adults currently enrolled in marketplace or Medicaid plans who obtained health care, 91 percent were very or somewhat satisfied with their plan doctors (Exhibit 9).

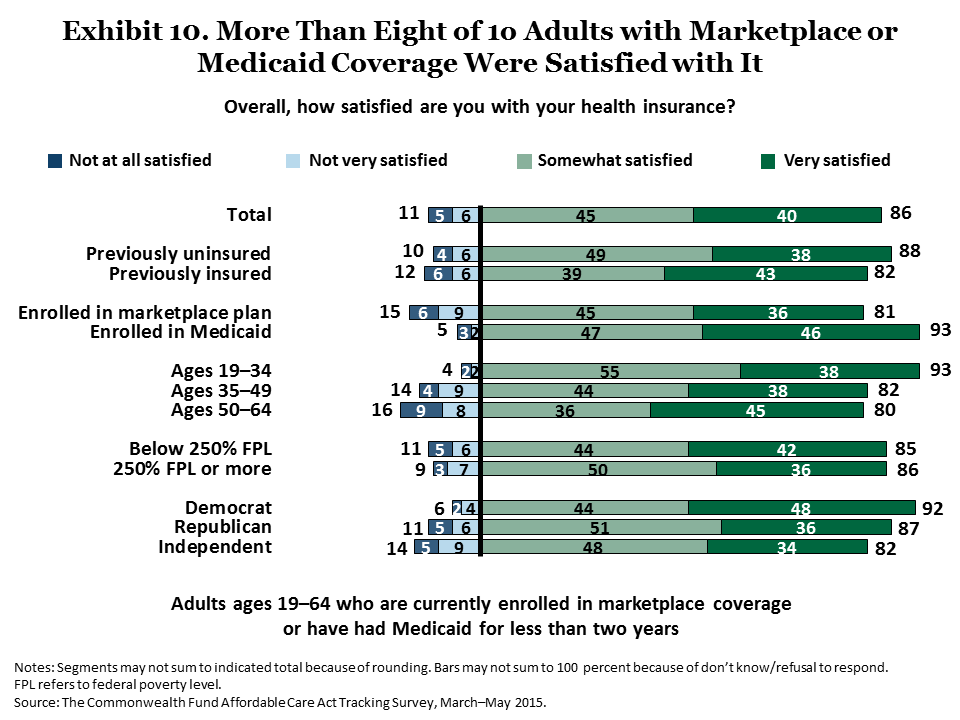

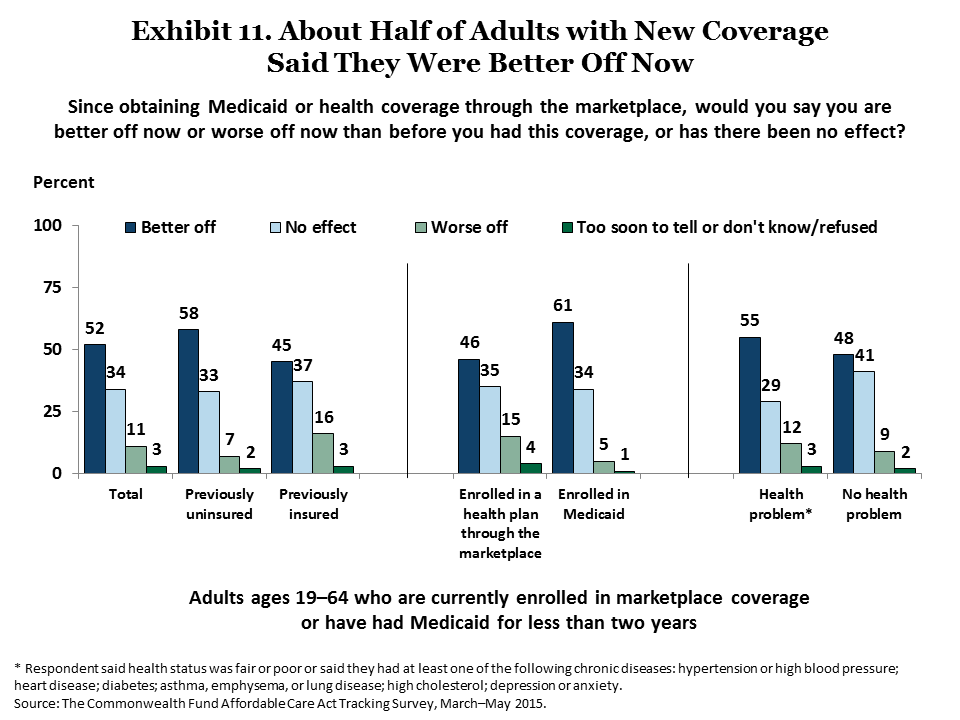

Satisfaction with the new ACA insurance coverage overall is also high. More than eight of 10 (86%) adults were very or somewhat satisfied with their health plans. This was true regardless of respondents’ age, insurance type, income level, or political affiliation (Exhibit 10). Slightly more than half (52%) of ACA-covered adults consider themselves to be better off now than they were before (Exhibit 11). Adults with Medicaid coverage were somewhat more likely to say they were better off now than those with marketplace coverage.

Challenges Ahead: Many Adults Remain Uninsured

According to the survey, an estimated 25 million working-age adults remained uninsured as of March–May 2015. Though this is a significant improvement from 2013 when the survey found an estimated 37.1 million adults uninsured, it suggests that more work is needed by state and federal governments to help people enroll. We use the survey data to examine the demographics of the remaining uninsured and to explore the potential factors that may have contributed to the slowdown in coverage gains, particularly among younger adults and low-income adults noted earlier.

Compared with the overall adult population, those who remain uninsured are disproportionately younger, poorer, and Latino (Table 2). One factor behind these higher rates of uninsurance in these groups may be the decision by 22 states not to expand eligibility for Medicaid: adults in these states comprise 41 percent of the overall population but 57 percent of the remaining uninsured.11 People living in states that have not expanded Medicaid are eligible for subsidized insurance through the marketplaces if their incomes are 100 percent of poverty or higher ($11,670 for an individual and $23,850 for a family of four). Others with incomes below that fall into the so-called “coverage gap”—their incomes are not high enough to qualify for subsidies and too high to qualify for their state’s existing Medicaid program, which in most states includes only children and very-low-income parents.

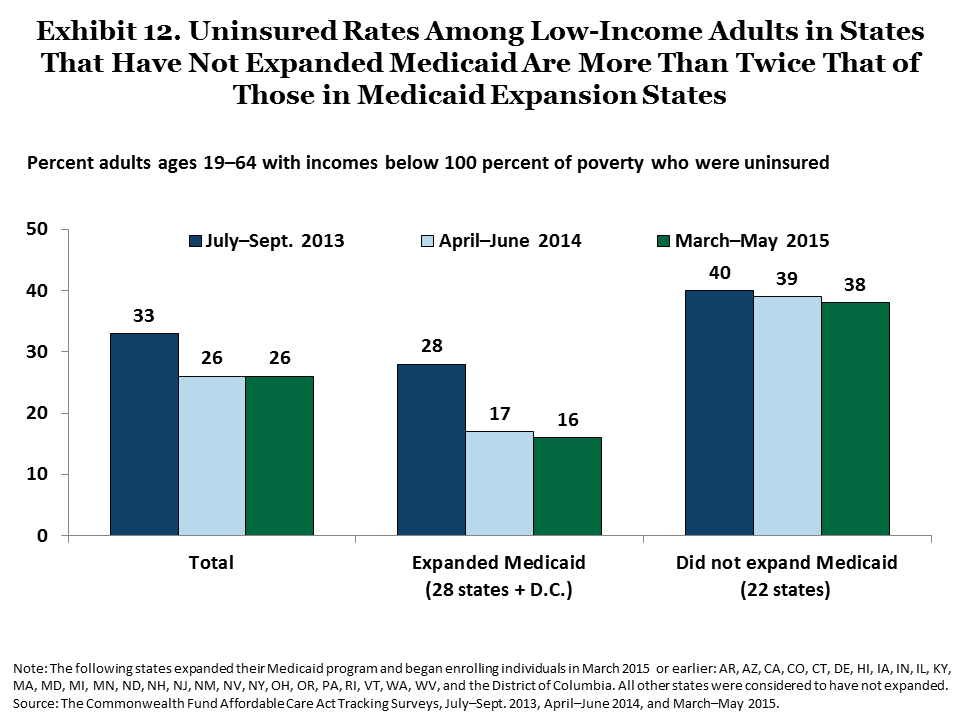

In the 22 states that have not expanded Medicaid, nearly two of five (38%) adults with incomes under 100 percent of poverty are uninsured, more than double the rate (16%) of those living in states that have expanded eligibility (Exhibit 12). Of the total number of remaining uninsured adults with incomes under 100 percent of poverty, 64 percent are living in states that have yet to expand Medicaid (data not shown). Among currently uninsured young adults, 28 percent have incomes under 100 percent of poverty and are living in states that have yet to expand their Medicaid programs (data not shown).

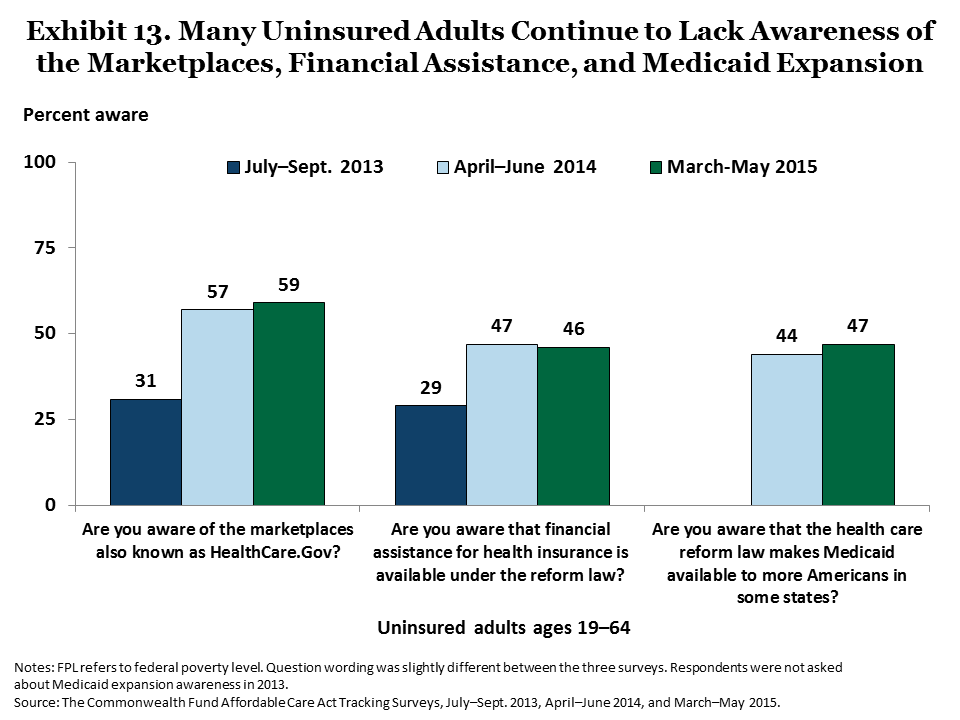

Another factor that is likely slowing improvement in coverage rates is lack of awareness of the insurance options available. Awareness of the marketplaces and the financial assistance available to help pay for health insurance rose significantly among uninsured adults from 2013 to 2014, but did not change between 2014 and 2015 (Exhibit 13). Less than half (47%) of uninsured adults are aware of expanded eligibility for Medicaid.

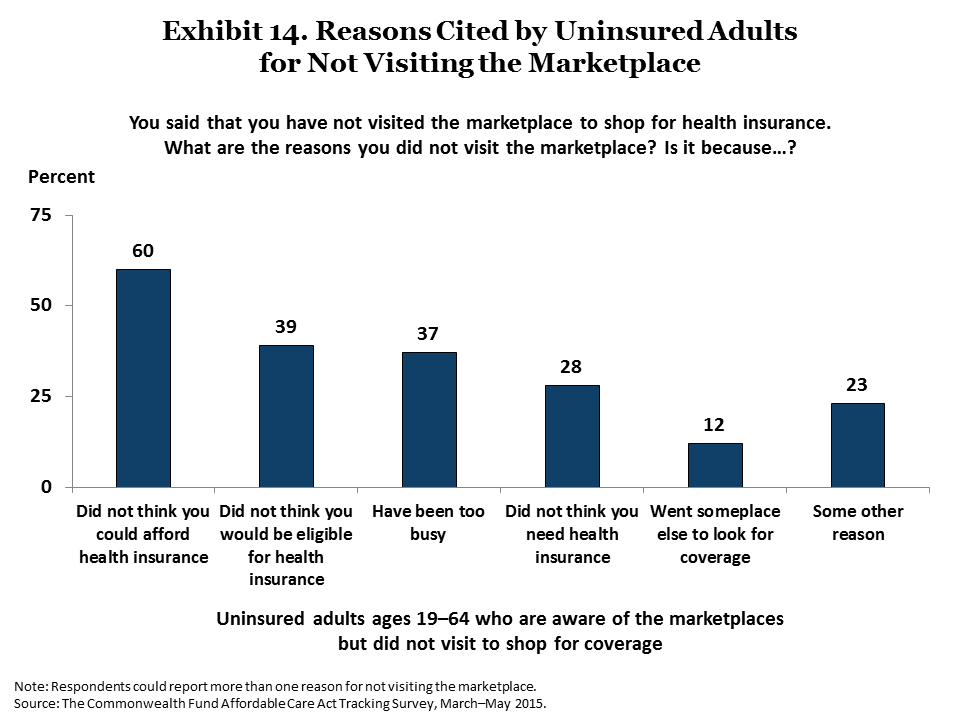

Among uninsured adults who are aware of the marketplaces, there is some skepticism about affordability as well as some reluctance to explore options. We asked uninsured adults who were aware of the marketplaces why they had not visited one to shop for coverage. Three of five (60%) said they had not gone to the marketplace to get health insurance because they did not think they would be able to afford coverage, 39 percent said they did not think they would be eligible, 37 percent had been too busy, and 28 percent said they did not think they needed it (Exhibit 14).

As written, the Affordable Care Act will ultimately stop short of achieving universal coverage since people who are not legal residents of the U.S. are barred from Medicaid or marketplace coverage. Some uninsured adults who said they didn’t think they would be eligible for coverage may fall into this category. It is also likely a significant factor contributing to the large number of Latinos who remain uninsured.

Conclusion

The Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey finds that the number of U.S. uninsured adults has fallen by an estimated 12.1 million since the major coverage expansions went into effect, but that gains slowed in 2015. The findings suggest that further gains in coverage among those most at risk of being uninsured will be stymied by states’ decisions not to expand eligibility for Medicaid. In addition, many uninsured adults are either unaware of the coverage options available to them or have reasons for not exploring their insurance options. Another looming risk to further improvements in coverage is the pending Supreme Court decision in the King v. Burwell case. If the Court decides against the government, coverage gains made among adults in the 34 states with federally run marketplaces will almost certainly be reduced—if not erased.12 To realize the potential of the Affordable Care Act to achieve near-universal coverage, federal and state policymakers and those eligible for coverage will need to fully utilize the resources and tools made available to them under the law.

Table 1. Among Adults Who Have Used Their Plans to Get Care, 62 Percent Said They Would Not Have Been Able to Access or Afford This Care Before

Adults ages 19–64 who are currently enrolled in marketplace coverage or have had Medicaid for less than two years and have used their new coverage

| Prior to getting this coverage, would you have been able to access and/or afford this care? | No (%) |

| Total | 62 |

| Poverty | |

| <250% federal poverty level | 69 |

| 250% federal poverty level or more | 34 |

| Prior insurance status | |

| Previously uninsured | 73 |

| Previously insured | 47 |

| Current coverage type | |

| Enrolled in a health plan through the marketplace | 48 |

| Enrolled in Medicaid | 78 |

| Marketplace type | |

| State-based marketplace | 62 |

| Federally facilitated marketplace | 61 |

Source: The Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey, March–May 2015.

Table 2. Demographics of Overall Sample, Uninsured Adults, and Marketplace and Medicaid Enrollees

| Total adults (19–64) |

Uninsured adults |

Total current marketplace and Medicaid enrollees* |

Enrolled in a health plan through the marketplace |

Enrolled in Medicaid |

|

| Unweighted n | 4,881 | 702 | 811 | 458 | 344 |

| Prior coverage status | |||||

| Uninsured | — | — | 59 | 53 | 66 |

| Insured | — | — | 41 | 47 | 33 |

| Age | |||||

| 19–34 | 32 | 47 | 38 | 31 | 46 |

| 35–49 | 32 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 32 |

| 50–64 | 34 | 21 | 30 | 36 | 22 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 62 | 42 | 51 | 51 | 50 |

| Black | 13 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Latino | 17 | 33 | 28 | 26 | 31 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 1 |

| Other/Mixed | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Poverty status | |||||

| Below 138% poverty | 30 | 55 | 44 | 27 | 63 |

| 138%–249% poverty | 19 | 23 | 30 | 37 | 23 |

| 250%–399% poverty | 14 | 9 | 11 | 14 | 6 |

| 400% poverty or more | 36 | 13 | 15 | 21 | 8 |

| Health status | |||||

| Fair/Poor health status, or any chronic condition or disability^ |

53 | 54 | 56 | 52 | 61 |

| No health problem | 47 | 46 | 44 | 48 | 39 |

| Political affiliation | |||||

| Democrat | 31 | 24 | 33 | 37 | 29 |

| Republican | 18 | 11 | 12 | 14 | 9 |

| Independent | 24 | 26 | 28 | 24 | 32 |

| Something else | 18 | 22 | 18 | 17 | 19 |

| State Medicaid expansion decision** |

|||||

| Expanded Medicaid | 58 | 43 | 62 | 54 | 73 |

| Did not expand Medicaid | 41 | 57 | 37 | 45 | 27 |

| Marketplace type*** | |||||

| State-based marketplace |

36 | 30 | 37 | 35 | 39 |

| Federally facilitated marketplace |

64 | 70 | 63 | 64 | 61 |

| Adult work status | |||||

| Full-time | 51 | 39 | 35 | 48 | 18 |

| Part-time | 14 | 14 | 23 | 21 | 27 |

| Not working | 35 | 46 | 42 | 31 | 55 |

| Employer size^^ | |||||

| 1–24 employees | 27 | 52 | 47 | 54 | 35 |

| 25–99 employees | 12 | 19 | 18 | 13 | 28 |

| 100–499 employees | 14 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 13 |

| 500 or more employees | 44 | 14 | 20 | 20 | 21 |

* Includes those currently enrolled in marketplace coverage, those who signed up for Medicaid through the marketplace, those who signed up for coverage through the marketplace but are not sure if it is Medicaid or private coverage, and those who have been enrolled in Medicaid for less than two years.

** The following states expanded their Medicaid program and began enrolling individuals in March 2015 or earlier: AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, HI, IA, IN, IL, KY, MA, MD, MI, MN, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, WV, and the District of Columbia. All other states were considered to have not expanded.

*** The following states have state-based marketplaces: CA, CO, CT, HI, ID, KY, MA, MD, MN, NM, NV, NY, OR, RI, VT, WA, and the District of Columbia. All other states were considered to have federally facilitated marketplaces.

^ At least one of the following chronic conditions: hypertension or high blood pressure; heart disease; diabetes; asthma, emphysema, or lung disease; high cholesterol; or depression or anxiety.

^^ Base: full- and part-time employed adults ages 19–64.

— Not applicable.

Source: The Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey, March–May 2015.

Appendix. Comparison of Uninsured Estimates from Recent Surveys

Several health policy research organizations have conducted surveys to capture the change in coverage since implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Each of these surveys uses slightly different methods, but they all were conducted over similar time periods with a baseline survey measuring the uninsured rate prior to the implementation of the health reform law’s major coverage provisions and follow-up surveys after implementation began. Although the surveys have produced slightly different estimates, they are directionally the same, showing a significant decline in the rate and number of uninsured adults in the United States. The surveys’ estimates of the changes in millions of adults who are uninsured are all within the confidence intervals of each other.

Survey Estimates of Changes in U.S. Uninsured Rates Since 2013

| Survey | Pre- implementation uninsured rate (%) [95% CI] |

Post- implementation uninsured rate (%) [95% CI] |

Change in millions uninsured [95% CI] |

| The Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey |

20% [18.5% — 21.4%] |

13% [12.0% — 14.7%] |

— 12.1 million [— 6.6 million to — 17.6 million] |

| ASPE Analysis of Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Indexa |

20.3% | 13.2% | — 14.1 million |

| Urban Institute Health Reform Monitoring Surveyb |

17.6% | 10.1% | — 15.0 million [— 11.9 million to — 18.1 million] |

| RAND Health Reform Opinion Surveyc |

— | — | — 16.9 million [— 11.1 million to — 22.7 million] |

Notes: Confidence intervals are shown where they were reported out by the organization. Urban Institute reported a 95% confidence interval of [5.9 — 9.1] surrounding its 7.5 percentage-point decrease in the uninsured rate.

— Percent estimates were not reported.

a Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, "Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act" (Washington, D.C.: ASPE, May 5, 2015).

b S. K. Long, M. Karpman, G. M. Kenney et al., “Taking Stock: Gains in Health Insurance Coverage Under the ACA as of March 2015” (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Health Policy Center), April 16, 2015.

c K. G. Carman, C. Eibner, and S. M. Paddock, “Trends in Health Insurance Enrollment, 2013–15,” Health Affairs Web First, published online May 2015.

Methodological Differences Between Private Surveys

| Survey | Population | Time frame | Sample frame | Response rate |

| The Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey |

U.S. adults ages 19 to 64 |

July–Sept. 2013 to March–May 2015 |

Dual-frame, RDD telephone survey |

2013: 20.1% 2015: 12.8% |

| ASPE Analysis of Gallup-Healthways Well-Being Indexa |

U.S. adults ages 18 to 64 |

Oct. 2013 to March 2015 |

Dual-frame, RDD telephone survey |

7% |

| Urban Institute Health Reform Monitoring Surveyb |

U.S. adults ages 18 to 64 |

Sept. 2013 to March 2015 |

KnowledgePanel— probability-based internet panel of 55,000 households |

Approximately 5% each quarter |

| RAND Health Reform Opinion Surveyc |

U.S. adults ages 18 to 64 |

Sept. 2013 to February 2015 |

American Life Panel— internet panel of 5,500 adults |

9% |

Notes: Information for this table was gathered from recent survey data releases and from an Urban Institute report comparing surveys, which can be found at: M. Karpman, S. K. Long, and M. Huntress, “Nonfederal Surveys Fill a Gap in Data on ACA” (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute, March 13, 2015).

a Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, "Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act" (Washington, D.C.: ASPE, May 5, 2015).

b S. K. Long, M. Karpman, G. M. Kenney et al., “Taking Stock: Gains in Health Insurance Coverage Under the ACA as of March 2015” (Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute Health Policy Center), April 16, 2015.

c K. G. Carman, C. Eibner, and S. M. Paddock, “Trends in Health Insurance Enrollment, 2013–15,” Health Affairs Web First, published online May 2015.

How This Survey Was ConductedThe Commonwealth Fund Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey, March–May 2015, was conducted by SSRS from March 9, 2015, to May 3, 2015. The survey consisted of 16-minute telephone interviews in English or Spanish and was conducted among a random, nationally representative sample of 4,881 adults, ages 19 to 64, living in the United States. Overall, 2,203 interviews were conducted on landline telephones and 2,678 interviews on cellular phones, including 1,729 with respondents who lived in households with no landline telephone access. For a list of survey questions analyzed in this brief, please click here. This survey is the third in a series of Commonwealth Fund surveys to track the implementation and effects of the Affordable Care Act. The first was conducted by SSRS from July 15 to September 8, 2013, by telephone among a random, nationally representative U.S. sample of 6,132 adults ages 19 to 64. The survey had an overall margin of sampling error of +/– 1.8 percent at the 95 percent confidence level. The second survey in the series was conducted by SSRS from April 9 to June 2, 2014, by telephone among a random, nationally representative U.S. sample of 4,425 adults ages 19 to 64. The survey had an overall margin of sampling error of +/– 2.1 percent at the 95 percent confidence level. The sample for the April–June 2014 survey was designed to increase the likelihood of surveying respondents who were most likely eligible for new coverage options under the ACA. As such, respondents in the July–September 2013 survey who said they were uninsured or had individual coverage were asked if they could be recontacted for the April–June 2014 survey. SSRS also included prescreened sample of households reached through their omnibus survey where interviews were completed with respondents ages 19 to 64 who were uninsured or had individual coverage prior to the first open enrollment period for 2014 marketplace coverage. The March–May 2015 sample was also designed to increase the likelihood of surveying respondents who had gained coverage under the ACA. SSRS included a prescreened sample of households reached through their omnibus survey of adults (between November 5, 2014, and February 1, 2015) with respondents who were uninsured, had individual coverage, had a marketplace plan, or had public insurance. As in all waves of the survey, the main sample was stratified to maximize the number of interviews with persons reporting incomes 250 percent of the poverty level or lower to further increase the likelihood of surveying respondents eligible for the coverage options as well as allow separate analyses of responses of low-income households. The data are weighted to correct for the stratified sample design, the use of recontacted respondents from the omnibus survey, the overlapping landline and cellular phone sample frames, and disproportionate nonresponse that might bias results. The data are weighted to the U.S. 19-to-64 adult population by age by state (for seven state breaks: California, Texas, New York, Florida, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and all other states), gender by state, race/ethnicity by state, education by state, household size, geographic division, and population density using the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013 American Community Survey. Data are weighted to household telephone use parameters using the CDC’s 2014 National Health Interview Survey. The resulting weighted sample is representative of the approximately 187.8 million U.S. adults ages 19 to 64. Data for income, and subsequently for federal poverty level, were imputed for cases with missing data, utilizing a standard regression imputation procedure. The survey has an overall margin of sampling error of +/– 2.1 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level. The landline portion of the main-sample survey achieved a 16.9 percent response rate and the cellular phone main-sample component achieved a 13.3 percent response rate. The response rate for the prescreened sample is 4 percent. The final response rate for the full study takes into account the response rates provided for the main-sample survey, the prescreened sample, and the average response rate of the original SSRS omnibus survey from which prescreened sample was obtained. The overall response rate was 12.8 percent. |

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Robyn Rapoport, Arina Goyle, and Matt Anderson of SSRS; and David Blumenthal, Don Moulds, Deb Lorber, Chris Hollander, Paul Frame, Jen Wilson, David Squires, and Sarah Berk of The Commonwealth Fund.

Notes

1Medicaid and CHIP: March 2015 Monthly Applications, Eligibility Determinations and Enrollment Report, CMS Report (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 4, 2015); March 31, 2015 Effectuated Enrollment Snapshot (Washington, D.C.: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services).

2 All reported differences are statistically significant at the p<=0.05 level or better, unless otherwise noted.

3 The July–September 2013 uninsured estimate has a 95% confidence interval of [18.5% – 21.4%]. The April–June 2014 uninsured estimate has a 95% confidence interval of [13.5% – 16.2%]. The March–May 2015 uninsured estimate has a 95% confidence interval of [12.0% – 14.7%].

4 The 95% confidence interval for the estimated decline in millions of adults who were uninsured is [6.6 million – 17.6 million].

5 The overall group of adults enrolled in marketplace plans or Medicaid includes respondents who said they were currently enrolled in a marketplace plan, currently enrolled in Medicaid and had had it for less than two years, chose a plan or enrolled in Medicaid through the marketplace, or were currently enrolled in coverage they got through the marketplace but were unsure if it was marketplace or Medicaid. When we look at marketplace and Medicaid enrollees separately, those who were unsure of their coverage type are excluded.

6 S. R. Collins, P. W. Rasmussen, M. M. Doty, and S. Beutel, The Rise in Health Care Coverage and Affordability Since Health Reform Took Effect (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Jan. 2015); S. R. Collins, C. Schoen, K. Davis, A. K. Gauthier, and S. C. Schoenbaum, A Roadmap to Health Insurance for All: Principles for Reform (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 2007); Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Consequences of Uninsurance, Care Without Coverage: Too Little, Too Late (Washington D.C.: National Academies Press, 2002).

7 S. R. Collins, P. W. Rasmussen, S. Beutel, and M. M. Doty, The Problem of Underinsurance and How Rising Deductibles Will Make It Worse—Findings from the Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, May 2015).

8 We note that the sample sizes are small on these questions. 159 people with marketplace or Medicaid coverage had looked for a new primary care physician, 151 found a physician. 308 people needed to see a specialist. These are similar in size to sample sizes in 2014 on these questions, which found largely similar responses. See the supplemental document for question wording.

9 S. R. Collins, P. W. Rasmussen, and M. M. Doty, Gaining Ground: Americans’ Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care After the Affordable Care Act’s First Open Enrollment Period (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, July 2014).

10 A 2011 Commonwealth Fund survey of 19-to-64-year-old adults found that among those insured all year who had tried to find a primary care physician in the past three years (either respondent or spouse/partner), 57 percent got an appointment within two weeks including 35 percent who got an appointment within one week and 22 percent within one to two weeks. See S. R. Collins, R. Robertson, T. Garber, and M. M. Doty, The Income Divide in Health Care: How the Affordable Care Act Will Help Restore Fairness to the U.S. Health System (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Feb. 2012). In the Commonwealth Fund 2013 International Survey, among adults age 18 and older, including those 65 and older as well as uninsured adults, 76 percent of adults who needed to see a specialist in the U.S. were able to get an appointment within four weeks. C. Schoen, R. Osborn, D. Squires, and M. M. Doty, “Access, Affordability, and Insurance Complexity Are Often Worse in the United States Compared to 10 Other Countries,” Health Affairs Web First, published online Nov. 14, 2013.

11 The following 28 states had expanded their Medicaid program and began enrolling individuals before this survey went into the field in March 2015: AR, AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, HI, IA, IL, IN, KY, MA, MO, MI, MN, ND, NH, NJ, NM, NV, NY, OH, OR, PA, RI, VT, WA, and WV, as well as the District of Columbia. All other states were considered to have not expanded their program. For more information, please see: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/interactives-and-data/maps-and-data/medicaid-expansion-map.

12 J. Ario, M. Kolber, and D. Bachrach, “King v. Burwell: What a Subsidy Shutdown Could Mean for Consumers,” The Commonwealth Fund Blog, Feb. 24, 2015.