Transformation of the maternity care system will require new models of health care delivery developed with input from community stakeholders and designed to reduce racial health inequities.3 Such models are being examined not only for their overall effectiveness and cost-savings potential but specifically for their likelihood to improve maternity care for people of color and those with low income. The need for new approaches has perhaps never been greater: as the coronavirus pandemic continues to rage in the U.S., evidence shows that Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous women are being disproportionately affected by COVID-19 during pregnancy.4

In this issue brief, we review the evidence for new maternity care models and discuss how policymakers, payers, providers, and health care systems can help to advance them.

INCORPORATING DIVERSE GROUPS OF HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS

Community-based doulas and nurse-midwifery care are rooted in the centuries-old practice of women receiving help from other women during childbirth, and a growing demand from women to have greater agency during their own birth process.5

Community-Based Doulas

What They Are and What They Do: Community-based doulas are trusted individuals, often from local communities, who are trained to provide psychosocial, emotional, and educational support during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period.6 They are particularly critical in labor and delivery, serving as patient advocates, and providing comfort and coaching. Community-based doula programs build on the strong relationship doulas establish with mothers throughout pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period to promote ongoing care and support.7

Evidence of Effectiveness: Doulas can improve perinatal and postpartum outcomes while being cost-effective, particularly for those facing inequities in birth outcomes.8 For example, those at high risk for adverse birth outcomes receiving care from doulas, compared with those not receiving care from doulas, are:

- Two times less likely to experience a birth complication

- Four times less likely to have a low birthweight baby

- More likely to breastfeed

- More likely to be satisfied with their care.9

Capacity to Advance Equity: The evidence suggests doulas are beneficial particularly for women of color, low-income women, and other marginalized communities. For example, a study of Medicaid beneficiaries receiving doula support found lower rates of C-sections and preterm births, compared with other pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid.10 Similar findings were reported for a community-based doula program serving predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods in New York City.11 Additionally, a recent study in California found that doulas have the potential to provide a “buffer” against racism in health care for pregnant women of color by providing patient-centered, tailored, and culturally appropriate care.12

To enable community-based doulas to provide care for Medicaid beneficiaries, fair compensation for doula work is critical. At least five states (Indiana, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon) have passed legislation implementing third-party reimbursement for doula services through Medicaid.13 Unfortunately, during the COVID 19 pandemic, certain states have had to pull back their focus on these programs. Low reimbursement rates as well as expensive, time-consuming licensure processes may also need to be addressed, as they create barriers to entry into community-based doula work.

Midwives

What They Are and What They Do: Midwives provide reproductive health care and attend births in multiple settings including at home, in a birth center, or in the hospital. They oversee the spectrum of maternity care, helping birthing people to identify their labor preferences and the appropriate site of delivery. Many individuals prefer working with midwives over M.D.s.14

Evidence of Effectiveness: The positive impact of midwifery on maternity care outcomes is well documented. An extensive literature review shows midwife-led maternity care results in substantially higher rates of vaginal delivery and lower rates of C-sections, as well as significantly lower rates of preterm births and low-birthweight infants compared with other maternity models.15

Although integration of midwives into health systems is demonstrated to be a key determinant of optimal maternal–newborn outcomes, only 8 percent of births nationally are delivered by certified nurse midwives.16 Rates vary significantly by states, in part because of differences in scope of practice laws that may limit what services midwives are permitted to provide independently.

Capacity to Advance Equity: There is less evidence on the success of midwifery at reducing racial inequities, perhaps because of the shifting demographic makeup of midwives themselves.17 In 2019, 49 percent of births in the U.S. were to people of color, but the nurse midwifery workforce remained 90 percent white.18 This reflects the historical exclusion and denigration of the long tradition of Black midwifery in the U.S. Prior to the early 20th century, the majority of U.S. births were attended by Black or immigrant lay midwives.19

For nurse midwifery to effectively address racial disparities in birth outcomes, one policy option is intentional investment in pipelines to train a racially and culturally diverse midwifery workforce. This may be especially valuable, as evidence suggests that racial concordance between provider and patient can improve satisfaction and quality of care.20

OFFERING NON-HOSPITAL-BASED CARE

Freestanding Birth Centers

What They Are and What They Do: Birth centers are stand-alone facilities that provide prenatal and labor and delivery care. They emphasize relationship-building between providers and pregnant people, and patient-centered birth planning and labor. Unlike costly hospital-based labor and delivery, birth centers are midwifery-led and typically do not employ anesthesiologists, obstetricians, and pediatricians. Because of this, birth centers are only recommended for low-risk labors.21

Evidence of Effectiveness: Birth centers reduce the number of interventions used in the course of labor and delivery while improving patient experience and lowering costs — saving more than $1,000 per birth.22 A review of 32 studies of birth centers found positive health outcomes for women, including lower rates of C-sections compared with women delivering in hospitals.23 Few severe maternal outcomes and no maternal deaths were reported in any of these studies, and overall, women were satisfied with the comprehensive, personalized care that they received. Another recent study of more than 15,000 birth center labors found only 6 percent resulted in C-sections with no maternal deaths.24 Although less consistent, some research also suggests improved infant outcomes.25

Hospital-affiliated birth centers may be particularly effective because they ensure higher levels of care are available in an emergency.26 For example, birth centers may be colocated with hospitals, with midwives maintaining admitting privileges. Some states also are leveraging the birth center model during the COVID-19 pandemic as a safe alternative to overcrowded hospitals and to prevent infection for birthing parents.27

Capacity to Advance Equity: Black-owned, culturally sensitive birth centers are a promising means of reducing racial disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality.28 However, while there are more than 384 birth centers in the United States, it is estimated that only about 20 are led by people of color.29 Limited access to capital and resources is a significant barrier to people of color starting and owning birth centers. Another obstacle to the growth of birth centers is Medicaid’s limited, or sometimes lack of, reimbursement for the services they provide.

EXPLORING INNOVATIVE MODELS OF MATERNITY CARE

Group Prenatal Care

What It Is and What It Does: Group prenatal care has been widely tested as an alternative to traditional, individualized care. Under the model, providers offer the same physical health care services for individual patients, who also convene as a group for facilitated discussions on topics ranging from preparations for parenthood and stress management to breastfeeding and nutrition.30

Evidence of Effectiveness: Preliminary, observational studies on the impact of group prenatal care demonstrate reduced rates of preterm birth (upwards of 41%), neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admissions, low birthweight, and emergency department use during pregnancy, as well as increases in breastfeeding, patient and physician satisfaction, and parental knowledge of childbirth and child-rearing.31 A study of a group prenatal care program for pregnant Medicaid beneficiaries in South Carolina found the model was cost-effective; by preventing premature births, group prenatal care resulted in cost savings of $2.3 million for the state. However, some studies, particularly randomized clinical trials, found no differences in health outcomes like preterm births between women in group versus individual prenatal care.32 Whether group prenatal care programs were able to successfully move online during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the impact of that transition, remains an open question.

Capacity to Advance Equity: There is evidence that group prenatal care is particularly helpful for improving health outcomes among Black people with low income, suggesting the model could help reduce racial disparities in maternal and infant mortality.33 Despite the promising evidence, the use of this model is not widespread.34 Some have been piloting diverse, culturally centric models to increasing awareness and interest. One group program, EMBRACE, was developed to provide prenatal care integrated with intentional racial consciousness to Black mothers and Black pregnant people.35 Group prenatal care models can be culturally responsive and aware and have diverse staff and leadership that represent the community served.

Pregnancy Medical Homes

What They Are and What They Do: The pregnancy medical home (PMH) provides comprehensive perinatal health care. PMHs provide early prenatal care in the first trimester, expand patient access through increased office hours, and engage patients in shared decision-making.36 Teams are financially incentivized for achieving specific milestones toward these goals and for meeting program requirements, such as screening for risk, collaborating with a care coordinator, and using data and analytics to monitor their own performance.

Evidence of Effectiveness: A medical home pilot in Texas resulted in better outcomes, fewer emergency department visits, and fewer C-sections, while pilots in Wisconsin and Texas increased likelihood of attending a postpartum visit.37 North Carolina formed a PMH model in which teams of maternity care providers aim to prevent preterm births and reduce C-sections for individuals enrolled in Medicaid. The program resulted in a nearly 7 percent decrease in the low-birthweight rate among the state’s Medicaid population.38

Several states that have implemented PMHs have realized savings from decreased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.39 However, some evidence suggests PMH models are not as effective as other models like group prenatal care at preventing maternal and child mortality and morbidity, and reducing overall health care costs.40

Capacity to Advance Equity: There is promising evidence that the PMH model, with its integrated care teams that address behavioral health and social needs, could play a role in reducing racial disparities in maternity outcomes. For example, North Carolina had the second-lowest rate of maternal mortality of all 25 reporting states, according to 2018 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The state’s success in part may be the result of its PMH model, which was implemented among 95 percent of prenatal care providers who accept Medicaid payment.41

ROLE OF PAYMENT AND DELIVERY SYSTEM REFORM

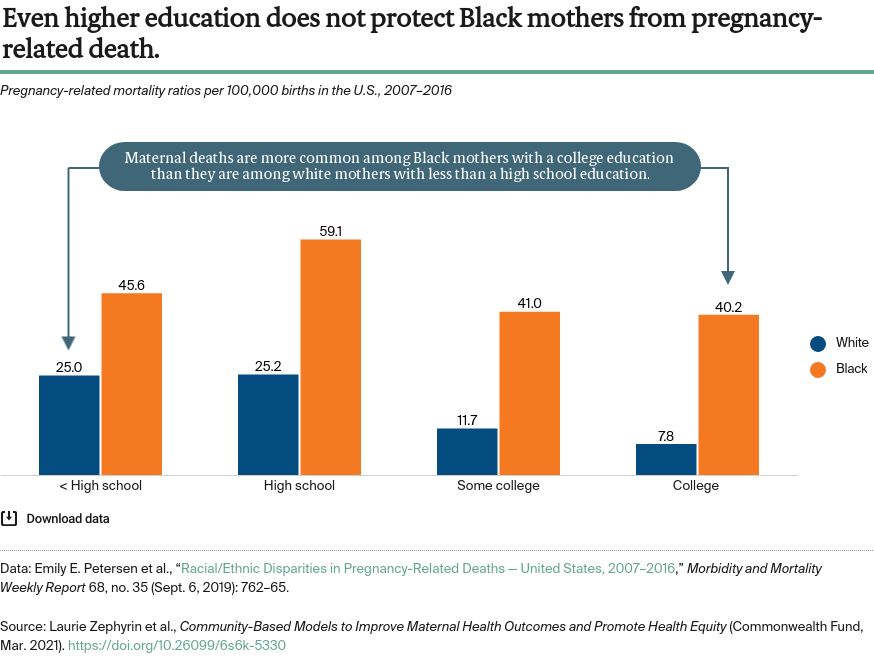

Equity-centered approaches to maternity care may help curb the rising rate of maternal mortality in the United States, particularly among women of color. Several approaches to maternity care have demonstrated that they can improve maternal and infant health outcomes — and, in some cases, reduce costs. To scale and spread these models, payment and delivery system reforms could focus on the following three areas:

- Expanding and improving reimbursement for the provider types that have helped reduce negative maternal and infant health outcomes, including doulas and midwives. States have a key role in defining scope of practice and allowing these providers to deliver services within their training and ability without physician supervision. The federal government also could financially support accreditation programs and create and expand loan forgiveness and training programs for these provider types to increase access to racially and culturally diverse maternity care providers.

- Improving access to services. The largest insurer of pregnant people, Medicaid, ends coverage for women 60 days postpartum, which leaves them without critical follow-up care. To reduce the racial inequities in maternal and infant morbidity and mortality, Medicaid coverage could be extended to at least one year postpartum. Additionally, Medicaid and other delivery system models could include more services addressing medical, behavioral, and social health needs.

- Incentivizing health systems and providers to adopt evidence-based models of care, like pregnancy medical homes, birth centers, and group prenatal care. Additionally, using value-based payments to incentivize use of equity-centered models could promote a more diverse set of providers and services. Creating accountability and incentives would help ensure that these policies and programs are equity-centered and create the desired outcomes.

CONCLUSION

A large and growing body of research suggests that a wide range of approaches could improve maternal health outcomes and the patient experience, while potentially reducing costs. This is especially true for those most at risk for negative outcomes, including people of color and those with low income.

As policymakers, providers, payers, and health system leaders rethink care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic, they may consider how these evidence-based models can be modified, leveraged, and expanded to ensure access to high-quality maternity care now and in the future.