Abstract

In addition to expanding eligibility for Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act reformed the program’s enrollment process, with the health insurance marketplaces playing a central role in the reforms. State-based marketplaces determine Medicaid eligibility, but federal regulations give states using the federal marketplace a choice either to allow the marketplace to make Medicaid eligibility determinations or to limit its role to assessing and referring applicants to the state Medicaid agency. This issue brief examines Medicaid enrollment data and finds that states that establish their own marketplaces realize higher Medicaid enrollment. In states that use the federal marketplace, Medicaid enrollment is higher when states have the marketplace determine eligibility. These findings underscore the importance of states’ marketplace decisions regarding Medicaid enrollment.

INTRODUCTION

In addition to expanding eligibility for the Medicaid program, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) changed the way in which people enroll in the program and renew coverage. During the development and passage of the law, it was assumed that the health insurance marketplaces would play a role in ensuring prompt and continuous coverage, which is associated with more appropriate use of health care.

This issue brief uses state Medicaid enrollment data to determine the impact of state policy choices about the marketplace. It aims to answer the following questions: 1) What difference, if any, does a state-based marketplace make to Medicaid enrollment? 2) What is the impact of a state’s decision to allow the federally facilitated marketplace to determine—rather than simply assess—Medicaid eligibility?

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT’S MEDICAID ENROLLMENT REFORMS

Historically, Medicaid enrollment was a paper-based process, partly because of the documentation needed to apply for welfare benefits and partly because states did not have the technology to permit the use of electronic documentation. States typically required applicants to physically present application forms and verification documentation. Between 1984 and 2009, a series of Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) reforms sought to streamline and simplify enrollment and retention using various strategies: enrollment assistance in community locations such as hospitals and community health centers, continuous enrollment, elimination of face-to-face interviews, simplified verification procedures, temporary eligibility, and “express lane” eligibility that used the results of one eligibility determination process (e.g., for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) to determine eligibility for other programs.1 These reforms were powered by advances in information technology, which have enabled online application and renewal along with electronic information transfer from a wide array of sources.

The ACA built on this history and adapted Medicaid enrollment to a new environment—the health insurance marketplace. Millions of people use the marketplace to seek financial assistance with the cost of health insurance from three closely aligned funding sources: subsidized private plans; Medicaid; and CHIP. Because the marketplace is technology-enabled,2 Medicaid was amended to support changes in technology that would enable the marketplace to communicate rapidly with state Medicaid programs. These changes helped to ensure that people applying for assistance over the course of a year—at the initial application stage, at renewal time, or during the year as their financial or other circumstances changed—could get efficient, one-stop help.3 This “no wrong door” policy applies to all states, regardless of whether they have opted for the Medicaid expansion.4 The ACA assumed that the marketplace would continuously determine eligibility and enroll people in appropriate subsidy programs.

Under the ACA, Medicaid’s enrollment reforms are designed to move toward a streamlined, electronic enrollment process (Exhibit 1). The enrollment reforms affect both application and renewal and are aimed at children and adults eligible for Medicaid because of poverty rather than disability (which remains subject to a more complex eligibility determination process). The ACA provides significantly enhanced federal funding to support an upgrade to enrollment technology, raising the federal matching rate from 50 percent to 90 percent, which has been permanently extended for systems that comply with certain criteria.5

Exhibit 1. The Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid Enrollment Reforms

|

Source: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, §2201.

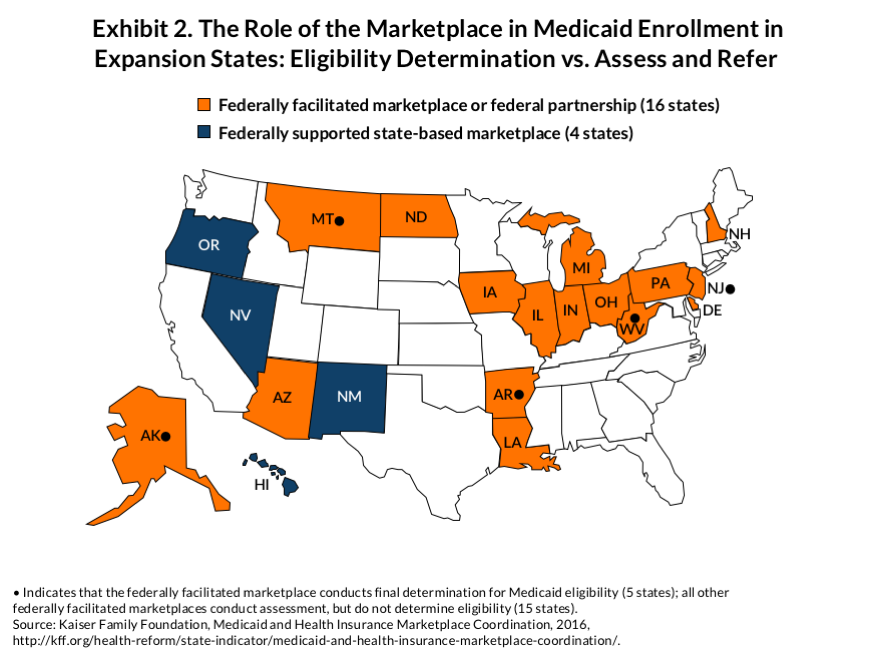

Regulations proposed in 20116 specified that the marketplace makes the final Medicaid eligibility determination in all states—those that built their own marketplaces and those using the federal marketplace. However, because states had concerns that marketplace decisions would increase Medicaid enrollment and because the federal marketplace was not finished, CMS modified its policy.7 Final rules issued in 20128 require that states using a state-based marketplace enable their marketplace to make final Medicaid determinations. But the rules give states that use the federal marketplace a choice: either the federal marketplace or their own Medicaid agencies make the final determination. States that choose to have their Medicaid agencies make the final eligibility determination limit the federal marketplace to an assessment and referral role.9 Of 20 Medicaid expansion states that either use the federal marketplace exclusively or as the technology platform for a state-based marketplace, 15 have selected the assessment and referral option (Exhibit 2). Among all 38 states that rely on the federal marketplace (including those that have expanded Medicaid and those that have not), 30 have taken the assessment option. Thus, while a fully integrated approach to Medicaid enrollment is a feature of state-based marketplaces, the common approach in states using the federal marketplace is to limit marketplace functions to assessment and referral.

MEDICAID ENROLLMENT PATTERNS IN MEDICAID EXPANSION STATES

Medicaid Enrollment Growth Concentrated in Expansion States

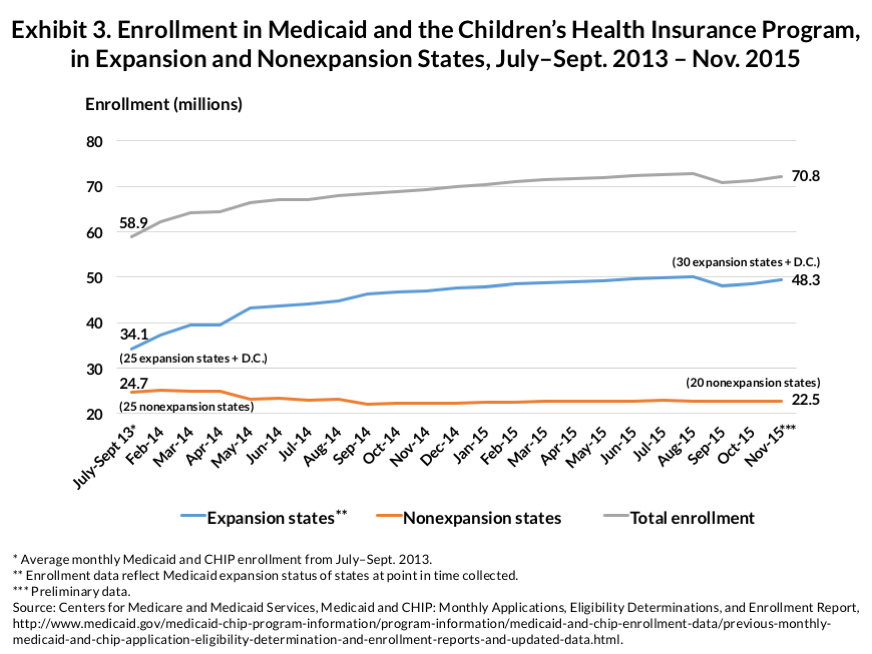

Exhibit 3, based on data reported through November 2015 by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), shows Medicaid and CHIP enrollment growth over time. (CMS includes CHIP data in its Medicaid enrollment reports.) The data indicate that the great majority of enrollment growth has occurred in states that expanded Medicaid. Over the two-year period covered by Exhibit 3, the number of nonexpansion states dropped, which helps explain the 10 percent decline in Medicaid enrollment in these states. Indeed, modest Medicaid enrollment growth has occurred in nonexpansion states, but at the same time, the CMS data show that enrollment growth is an expansion state phenomenon.

State-Based Marketplaces Spur Medicaid Enrollment Growth

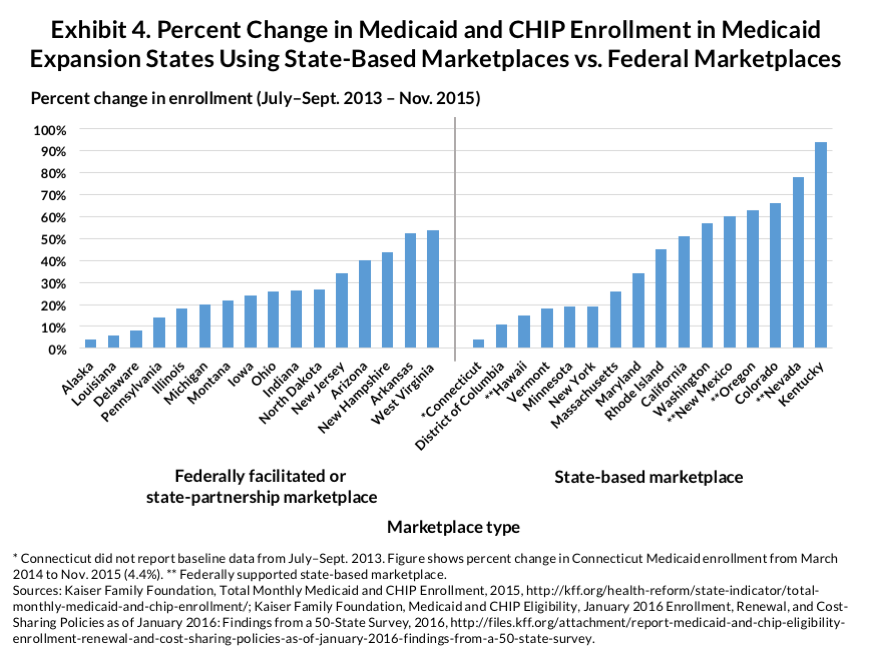

With Medicaid enrollment growth concentrated in the expansion states, the question is whether these states’ marketplace choices make a difference. Exhibit 4 shows that states that run their own marketplaces tend to achieve higher enrollment rates, possibly because these marketplaces require full integration of Medicaid enrollment into the marketplace enrollment process. Kentucky’s Kynect marketplace provides a particularly striking example.10 Kentucky achieved the highest Medicaid growth in the country, possibly because its popular Kynect system acted as a pathway into whichever program applicants qualified for. Given the poverty level among the population, the number of residents qualifying for Medicaid have far outstripped—by 554,53711 to 130,79012—the number qualifying for marketplace subsidies. These figures suggest that if Kentucky were to replace Kynect with the federal marketplace, the biggest impact may accrue to the state’s Medicaid program, especially if the state were to combine this shift with a move to an “assess-and-refer” approach to Medicaid enrollment, rather than allowing the federal marketplace to make Medicaid eligibility determinations. In other words, Medicaid enrollment in Kentucky could be adversely affected simply because once Kynect ends and the federal marketplace takes its place, the enrollment integration feature is lost. It would be likely that the impact would be felt not only by people making an initial Medicaid application but also among those trying to renew their coverage.

The states with federally supported state-based marketplaces also experienced high Medicaid enrollment growth. Three of the six states with the highest Medicaid enrollment growth (Nevada, New Mexico, and Oregon) use the HealthCare.gov platform to run their systems.13 This suggests that regardless of whether state or federal enrollment technology is used, a state-based marketplace can help ease communication between a state’s Medicaid program and the marketplace.

Greater Enrollment Linked to States That Allow the Federal Marketplace to Determine Eligibility

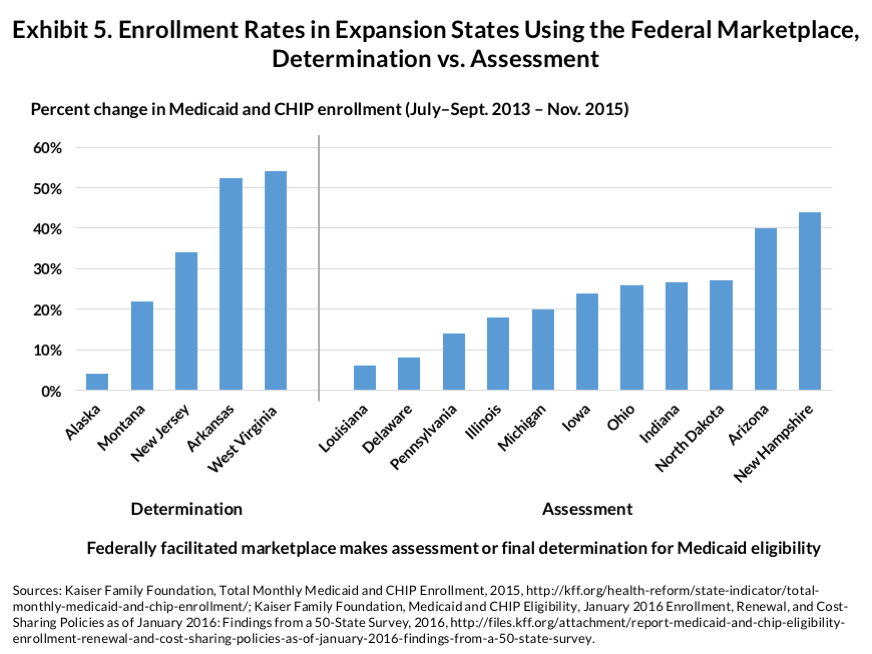

Exhibit 5 shows the impact of a state’s choice to allow the federal marketplace to determine eligibility for Medicaid rather than simply assess potential eligibility and refer applicants and application files to the state’s Medicaid program. States that use the determination model rather than assess-and-refer tend to experience higher Medicaid enrollment. This finding makes sense for two reasons. First, having to refer potentially eligible cases to a state Medicaid program adds an extra step to the process, possibly slowing down the final determination. Second, transferring electronic files between the federal marketplace and state Medicaid agencies can create technical problems and added disruptions. Even if the state agency is poised to make a rapid final determination, problems arising from file transfer can create complications.

DISCUSSION

This examination suggests that the choices states make regarding their marketplaces affect Medicaid enrollment. First, states that use a state-based marketplace have higher Medicaid enrollment, which may be attributable to greater ease of communication between two state agencies working in tandem. This trend is even observed in states that use the federal website, HealthCare.gov, for enrollment. But a key factor is likely the requirement that state-based marketplaces fully integrate the eligibility determination process. This is an important finding in the wake of Kentucky’s current decision to move away from a state marketplace toward the federal marketplace.14 Putting aside any efforts Kentucky might make to directly limit Medicaid eligibility by shifting to a §1115 expansion demonstration that uses tighter rules, simply moving to the federal marketplace can be expected to adversely affect Medicaid enrollment numbers, as applicants find it more difficult to obtain an initial eligibility determination and as the renewal process is slowed.

Second, our findings underscore the importance of continued investment in the technology needed to ensure smooth communication between the marketplace and Medicaid, especially in states that rely on the federal marketplace. Although the ACA offers significantly enhanced funding to support the cost of technology improvements in state Medicaid programs, such improvements may be of relatively limited utility unless the federal marketplace undergoes a similar technology transformation to support effective communication around Medicaid enrollment issues. High priority should be placed on improving the ability of the marketplace, whether state or federal, to smoothly communicate with state Medicaid programs. This is especially true in light of the “churning” issue, which causes low-income people to move back and forth between Medicaid and premium subsidies on a regular basis as life circumstances and income change. For health insurance coverage to be continuous for this population, full integration of Medicaid and marketplace enrollment functions is essential.

Notes

1 A. M. Weiss, “The Evolution of Medicaid/CHIP Outreach and Enrollment,” Presentation to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) (Portland, Maine: National Academy for State Health Policy, Feb. 20, 2014), https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2014FebruarySession3a.pdf; and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Letter to State Health Officials 13-003, “Facilitating Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment and Renewal in 2014,” May 17, 2013, https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/sho-13-003.pdf.

2 PPACA § 1311; 42 U.S.C. §18031(d)(4)(F).

3 B. Sommers and S. Rosenbaum, “Issues in Health Reform: How Changes in Eligibility May Move Millions Back and Forth Between Medicaid and Insurance Exchanges,” Health Affairs, Feb. 2011 30(2):2228–36.

4 Families USA, “Fact Sheet: Enrollment Policy Provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” (Washington, D.C.: Families USA, 2010), http://familiesusa.org/sites/default/files/product_documents/Enrollment-Policy-Provisions.pdf; and http://www.govhealthit.com, 2013.

5 42 C.F.R. § 433.112.

6 Medicaid Program; Eligibility Changes Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, 78 Fed. Reg. 51148 (proposed August 17, 2011) (to be codified at 42 CFR pts. 431, 433, 435, and 457), https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-08-17/pdf/2011-20756.pdf.

7 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “State Exchange Implementation Questions and Answers,” Nov. 29, 2011, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Files/Downloads/exchange_q_and_a.pdf; and T. S. Jost, “Implementing Health Reform: Medicaid and Exchange Eligibility Determinations,” Health Affairs Blog, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2011/08/13/implementing-health-reform-medicaid-and-exchange-eligibility-determinations/.

8 Medicaid Program; Eligibility Changes Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, 77 Fed. Reg. 57, 17144 (March 23, 2012) (codified at 42 CFR pts. 431, 435, and 457).

9 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “State Exchange Implementation Questions and Answers,” Nov. 29, 2011, https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Files/Downloads/exchange_q_and_a.pdf; and T. S. Jost, “Implementing Health Reform: Medicaid and Exchange Eligibility Determinations,” Health Affairs Blog, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2011/08/13/implementing-health-reform-medicaid-and-exchange-eligibility-determinations/.

10 Editorial Board, “Kentucky’s Bizarre Attack on Health Reform,” New York Times, Jan. 21, 2016.

11 This number represents the net change in Medicaid and CHIP enrollment through a comparison of November 2015 data to July–September 2013 average enrollment. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Kentucky: Monthly Medicaid and CHIP Enrollment Data,” https://www.medicaid.gov/state-overviews/stateprofile.html?state=kentucky.

12 Number of individuals eligible for financial assistance. Kaiser Family Foundation, “State Marketplace Statistics,” Dec. 2015, http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-marketplace-statistics/.

13 Oregon also engaged in extraordinary outreach efforts aimed directly at the Medicaid population when its marketplace was experiencing major technology-related problems.

14 A. Goodnough, “With Health Care Switch, Kentucky Ventures into the Unknown,” New York Times, Jan. 13, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/14/us/affordable-care-act-kentucky-insurance-exchange.html?_r=1.