Abstract

This brief analyzes experts’ reviews of evidence about care models designed to improve outcomes and reduce costs for patients with complex needs. It finds that successful models have several common attributes: targeting patients likely to benefit from the intervention; comprehensively assessing patients’ risks and needs; relying on evidence-based care planning and patient monitoring; promoting patient and family engagement in self-care; coordinating care and communication among patients and providers; facilitating transitions from the hospital and referrals to community resources; and providing appropriate care in accordance with patients’ preferences. Overall, the evidence of impact is modest and few of these models have been widely adopted in practice because of barriers, such as a lack of supportive financial incentives under fee-for-service reimbursement arrangements. Overcoming these challenges will be essential to achieving a higher-performing health care system for this patient population.

INTRODUCTION

Patients who have complex health needs account for a disproportionate share of health care spending or may be at risk of incurring high spending in the near future.1 These individuals typically suffer from multiple chronic health conditions and/or functional limitations.2 Moreover, their health care needs may be exacerbated by unmet social needs.3 They are often poorly served by current health care delivery and financing arrangements that fail to adequately coordinate care across different service providers and care settings.4

This brief describes research about clinical care models or care management programs implemented by health care provider organizations to improve outcomes and reduce costs for high-need, high-cost patients (see About This Study). Based on a review of literature that assesses the evidence on the impact and features of such care models or care management programs, this brief identifies common attributes of effective models and programs, as well as barriers to their uptake, to identify opportunities for improving health system performance. This literature synthesis is the first in a series of publications that will address this topic in more detail.

FINDINGS

Assessing the Evidence on the Value of Care Models

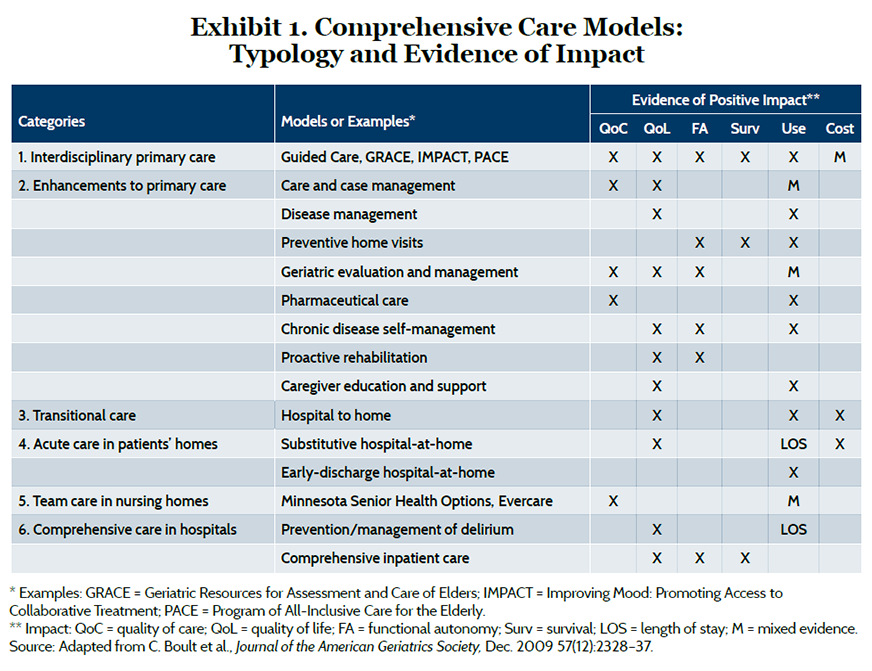

In a review conducted for the Institute of Medicine, Chad Boult and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins University identified 15 models of comprehensive care for older adults with chronic illness, which fit into six broad categories related to care settings.5 Exhibit 1 summarizes evidence of positive impact, which was most frequently observed in quality of care or patient’s quality of life. Most models reduced hospital use or length of stay, although the evidence was mixed in some cases. Three models—interdisciplinary primary care for heart failure patients, transitional care from hospital to home, and “hospital-at-home” programs that substitute care in the patient’s home in lieu of a hospital stay—showed some evidence of lower cost, although this was not directly measured in all studies.

A review conducted for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation by Thomas Bodenheimer and Rachel Berry-Millett, at the University of California, San Francisco, analyzed evidence on the effects of care management programs for patients with complex health care needs. They defined care management as “a set of activities designed to assist patients and their support systems in managing medical conditions and related psychosocial problems more effectively, with the aim of improving patients’ health status and reducing the need for medical services.”6 The strength of the evidence varied by site or modality of care (Exhibit 2). Studies of hospital-to-home transitions for patients with complex conditions exhibited the most consistently positive findings. Several studies offered convincing evidence that care management improved quality in primary care settings, but hospital use was reduced in only a few studies.

Exhibit 2. Summary of Evidence for Complex Care Management by Site and Modality of Care

| Site of Care Management | Impact on Quality | Impact on Hospital Use and/or Costs |

| Primary care | Improved (7 of 9 studies) | Some reduced use (3 of 8 studies) |

| Via telephone (vendor supported) | Some improvement | Inconclusive evidence |

| Integrated multispecialty group | Improved (2 of 3 studies) | Some reduced cost (1 of 3 studies) |

| Hospital-to-home transition | Improved (many studies) | Reduced use and cost (many studies) |

| Home-based | No clear evidence | No evidence |

Source: Adapted from T. Bodenheimer and R. Berry-Millett, Care Management of Patients with Complex Health Care Needs, Research Synthesis Report No. 19 (Princeton, N.J.: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dec. 2009).

A Congressional Budget Office report, authored by Lyle Nelson, reviewed evaluations of 34 disease management and care coordination programs for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries and found that only one-third reduced hospital use by 6 percent or more.7 Although the programs were developed under six different demonstrations (Appendix A), they shared a common feature: the use of nurses as care managers “to educate patients about their chronic illnesses, encourage them to follow self-care regimens, monitor their health, and track whether they received recommended tests and treatments.”8 The programs increased teaching about self-care, but had little effect on patients’ adherence to self-care and no systematic effects on care quality. Medicare realized net savings for only two programs: a care management program operated by Massachusetts General Hospital and its affiliated physicians and a telemedicine program operated by the Health Buddy Consortium (Appendix B).

Finally, Randall Brown at Mathematica Policy Research and colleagues9 at the University of Illinois, Chicago, found the following types of care models had the strongest evidence for reducing hospital use and costs of care for high need, high cost patients: select interdisciplinary primary care models (e.g., Care Management Plus developed at Intermountain Healthcare and Oregon Health and Science University); care coordination programs focused on high-risk patients (e.g., the Medicare Care Coordination Demonstration program implemented at Washington University); chronic disease self-management programs (e.g., the model developed at Stanford University); and transitional care interventions (e.g., Naylor Transitional Care Model developed at the University of Pennsylvania). (For more information on the specific programs cited, see Appendix B; for an example of how the Medicare Care Coordination Demonstration program was implemented at one site, see the box.)

Case Example: Washington University’s Care Coordination ProgramA natural experiment at Washington University, an academic medical center in St. Louis that participated in the Medicare Care Coordination Demonstration, illustrates the importance of program design. An evaluation found that the site had increased costs when relying on remote telephone care management of most of its enrollees during the first four years of participation in the demonstration. The site achieved net savings for Medicare after reconfiguring its program to focus on higher-risk patients through better assessment of health risks and more in-person contacts by local care managers, which in turn supported stronger transitional care. In addition, the supervised use of care manager assistants for patients at lower-risk levels helped nurse care managers focus greater attention on higher-risk patients. The redesign also improved comprehensive medication management and streamlined and standardized care planning, which promoted efficiency. Source: D. Peikes, G. Peterson, R. S. Brown et al., “How Changes in Washington University’s Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Pilot Ultimately Achieved Savings,” Health Affairs, June 2012 31(6):1216–26. |

Identifying Common Attributes of Successful Care Models

Interdisciplinary primary care models have demonstrated a range of positive outcomes and are of particular interest because they may have broad potential application in current practice. Chad Boult and Darryl Wieland, at Johns Hopkins University, distilled four features associated with more effective and efficient primary care for older adults with chronic illnesses.10 They are:

- comprehensive assessment of the patient’s health conditions, treatments, behaviors, risks, supports, resources, values, and preferences;

- evidence-based care planning and monitoring to meet the patient’s health-related needs and preferences;

- promotion of patients’ and family caregivers’ active engagement in care;

- and coordination and communication among all the professionals engaged in a patient’s care, especially during transitions from the hospital.

Bodenheimer and Berry-Millett identified several characteristics of more successful care management programs:

- selecting patients with complex needs but not those with illness so severe that palliative or hospice care would be more appropriate than care management;

- using specially trained care managers on multidisciplinary teams that include physicians; emphasizing person-to-person encounters, including home visits;

- coaching patients and families to engage in self-care and recognize problems early to avoid emergency visits and hospitalizations;

- and relying on informal caregivers in the home to support patients.

Nelson’s analysis of program design in the Medicare demonstrations found that the nature of interactions between care managers and patients and physicians was the strongest predictor of success in reducing hospital use. These interactions occurred in a variety of ways, such as by meeting patients in the hospital or occasionally accompanying patients on visits with their physician. In primary care practices affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital, care managers were embedded in the practices so that they had access to patient information and worked closely with physicians.11 When care-managed patients of these practices visited the emergency departments or were admitted to the hospitals, care teams received real-time notifications, which allowed them to intervene in a timely way. An analysis of the Medicare Care Coordination Demonstration (one of the six Medicare demonstrations examined by Nelson) by Randall Brown and colleagues at Mathematica Policy Research found that four different programs were more successful than others in reducing hospital use (by 11% on average) among a subset of enrollees at high risk of near-term hospitalization (Appendix A).

As a group, the four programs reduced Medicare spending by 5.7 percent for high-risk enrollees, although they were cost-neutral after accounting for administrative fees.12 These findings point to the importance of targeting those most likely to benefit, rather than all patients, and keeping intervention costs low to generate savings. The evaluators identified six practices that care coordinators performed in at least three of the four more-successful programs targeting high-risk beneficiaries:

- supplementing telephone calls to patients with frequent in-person meetings;

- occasional in-person meetings with providers; acting as a communications hub for providers;

- educating patients; helping patients manage medications;

- and providing timely and comprehensive transitional care after hospitalizations.

Although transitional care is receiving attention for its role in reducing hospital readmissions, it is only one of several interventions needed to improve outcomes for high-need, high-cost patients. Successful transitional care consists of several interrelated elements,13 which might be considered together as one feature in a broader care model.

Implementing Care Models Successfully: Context Matters

Some interventions with seemingly similar features achieve disparate results.14 Their relative success or failure may be attributed to how an intervention is executed, including social and technical aspects.15 Organizations that develop care management programs are not necessarily seeking to design broadly applicable models but an approach that works in a specific setting. For example, evaluators found the success of high-cost care management at Massachusetts General Hospital stemmed from an institutional commitment to developing a program tailored and fully integrated into its health care system.16

To this point, a recent examination of 18 primary care-integrated complex care management programs by Hong and colleagues17 identified common managerial and operational approaches:

- customizing the approach to the local context and caseload;

- using a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to identify patients;

- focusing on building trusting relationships with patients and their primary care providers;

- matching team composition and interventions to patient needs;

- offering specialized training for team members;

- using technology to bolster care management efforts.

Best practices may need to be customized to accommodate different populations’ needs and changes in technology. For example, a care manager’s role of serving as a “communications hub” may evolve as digital health technologies facilitate new ways of engaging patients and convening a virtual care team.18 Likewise, electronic teaching aids may help teach self-care to patients with low health literacy, while also lessening care managers’ workloads.19

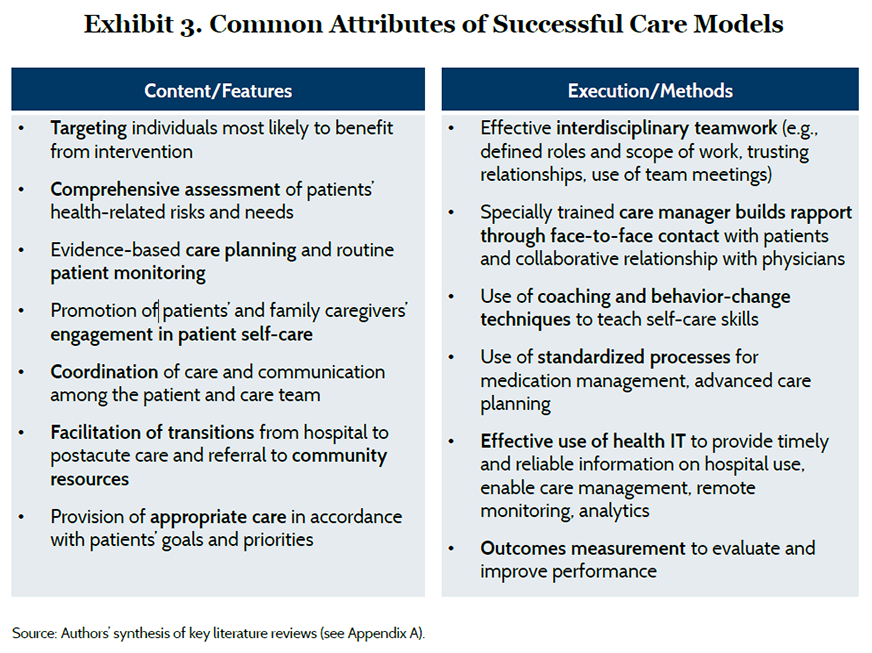

Putting the Pieces Together: Content and Execution

Our synthesis of the common attributes of successful care models, identified across multiple reviews, distinguishes between features that describe the general content of an intervention (i.e., what it does) and those related to the execution of that content (i.e., how it’s done) (Exhibit 3).

IMPLICATIONS

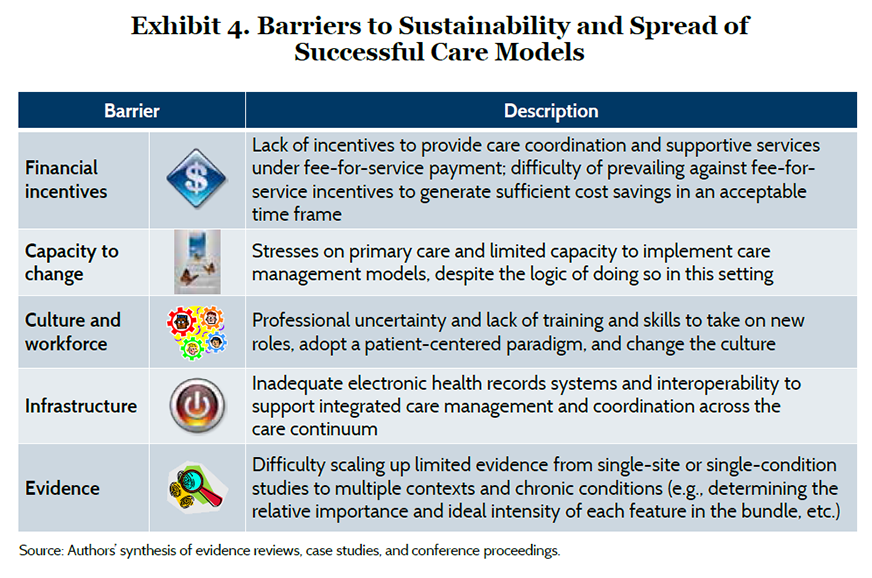

Overcoming Barriers to Sustainability and Spread

We identified five kinds of barriers or challenges to sustaining and spreading new care models (Exhibit 4), which help to explain why few of these models have been widely adopted in practice.20 Simply identifying barriers and enabling factors does not produce change. To advance the field, practitioners can use evidence-based implementation and dissemination frameworks, which have shown promise in helping to guide the adaptive design and spread of programs.21 Packaging tools, training, and technical assistance together with supportive financial incentives may increase the likelihood that local champions can develop capacity to take up effective programs and practices.22

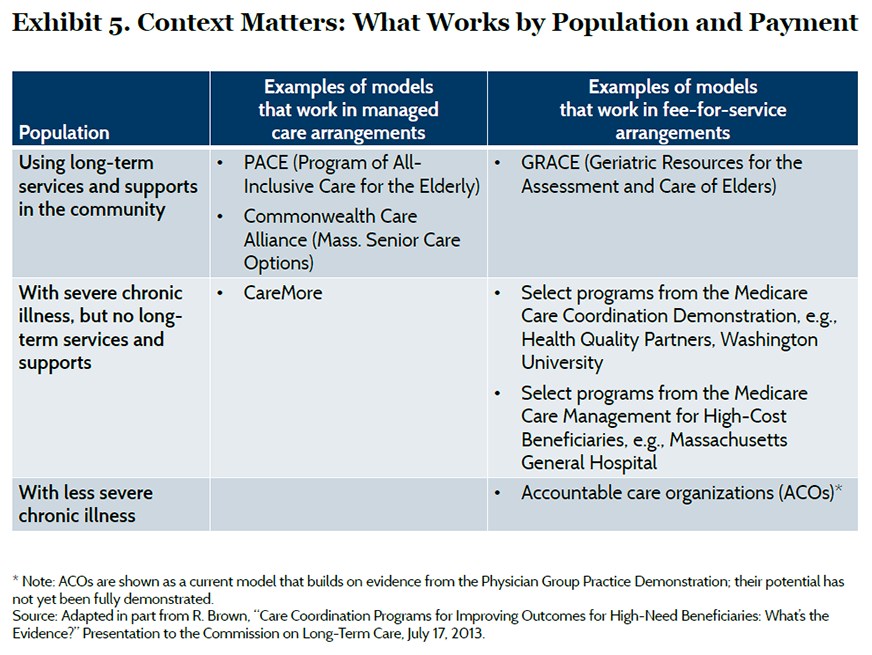

Applying the Evidence to Design Effective Programs for Particular Subpopulations

Care models are typically designed to meet the needs of particular population segments under different payment arrangements and organizational settings (Exhibit 5).23 For example, frail elderly patients with functional limitations who need long-term services and supports may benefit from a care model such as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), which offers a comprehensive set of services to support independent living by pooling funding from the Medicare and Medicaid programs. On the other hand, Medicare beneficiaries with serious chronic illnesses who do not need such long-term services and supports may benefit from a care model such as the Washington University care coordination program, which builds on existing provider relationships and fee-for-service payment. Assessing and monitoring high-risk patients can determine when their needs change and require an alternative care model. However, transitions between programs must be made seamlessly or will risk interrupting continuity of care. Some managed care organizations, such as the Visiting Nurse Service of New York, have developed a portfolio of programs based on common care management principles tailored to serve different segments of the population; this approach offers the opportunity to realize economies but also requires depth of expertise.24 Our synthesis is limited by a relative paucity of high-quality evidence on some care models, such as those that integrate long-term services and social supports into primary care. Much of the evidence reviewed comes from trials in single sites or programs that target patients with specific conditions, which raises questions about broader application. The findings of this brief will need to be augmented by new evidence from other approaches that are currently being tested.25

CONCLUSION

Care models for high-need, high-cost patients offer the potential to achieve the “triple aim” by reducing costs while simultaneously improving patients’ health and care experiences. Few of the care models examined in this brief have demonstrated net cost savings, which suggests that our expectations should be modest when adding care management to an already fragmented fee-for-service care system. The incentives created by accountable care and other value-based purchasing initiatives may strengthen the business case for adopting carefully designed and well-executed models.26 Public and private purchasers must consider the adequacy of payment methods and performance measurements to ensure that savings ultimately accrue to society or consumers while also attracting sufficient participation among providers and improving outcomes for patients.27

| About This Study We synthesized findings from six expert reviews and secondary analyses of evidence on the impact and features of clinical care models or care management programs that target high-need, high-cost patients—often defined as patients with complex health care needs. (Appendix A describes sources and definitions in detail; Appendix B describes characteristics of select care models.)

We also reviewed a best-practice framework for advanced illness care published by the Coalition to Transform Advanced Care. Although there was some overlap in the research studies included in the reviews, no single review encompassed all the evidence. Exclusions: Our primary focus was on care models sponsored by health care delivery organizations. Therefore, we did not select reviews focused on the effectiveness of capitated managed care plans or state-sponsored programs for Medicaid beneficiaries.28 (Some care models targeting these populations were included in the general reviews.) While care models often included behavioral health in comprehensive care, we did not include reviews focused specifically on interventions that integrate behavioral health in primary care, which may serve a broader population.29 Limitations: Individual research studies included in the reviews may not have been strictly comparable because of differences in intensity and scope of interventions, in populations served, and in duration of study periods. We did not ascertain whether the programs cited in the literature are still in existence. Many studies used reductions in hospitalizations to indicate the potential for reduced health care spending; however, this outcome depends on whether cost savings from reduced utilization exceed the costs of care enhancements and program administration, which was often not measured. |

Notes

1 J. A. Schoenman, The Concentration of Health Care Spending, NIHCM Foundation Data Brief (Washington, D.C.: National Institute for Health Care Management Research and Educational Foundation, July 2012).

2 L. Alecxih, S. Shen, I. Chan et al., Individuals Living in the Community with Chronic Conditions and Functional Limitations: A Closer Look (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Jan. 2010).

3 D. Bachrach, H. Pfister, K. Wallis et al., Addressing Patients’ Social Needs: An Emerging Business Case for Provider Investment (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, May 2014).

4 C. Schoen, R. Osborn, D. Squires, M. M. Doty, R. Pierson, and S. Applebaum, “New 2011 Survey of Patients with Complex Care Needs in Eleven Countries Finds That Care Is Often Poorly Coordinated,” Health Affairs Web First, published online Nov. 9, 2011; and S. M. Asch, E. A. Kerr, J. Keesey et al., “Who Is at Greatest Risk for Receiving Poor-Quality Health Care?” New England Journal of Medicine, March 16, 2006 354(11):1147–56.

5 C. Boult, A. F. Green, L. B. Boult et al., “Successful Models of Comprehensive Care for Older Adults with Chronic Conditions: Evidence for the Institute of Medicine’s ‘Retooling for an Aging America’ Report,” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Dec. 2009 57(12):2328–37.

6 T. Bodenheimer and R. Berry-Millett, Care Management of Patients with Complex Health Care Needs, Research Synthesis Report No. 19 (Princeton, N.J.: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Dec. 2009).

7 L. Nelson, Lessons from Medicare’s Demonstration Projects on Disease Management and Care Coordination, Working Paper 2012-01 (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Jan. 2012).

8 L. Nelson, Lessons from Medicare’s Demonstration Projects on Disease Management, Care Coordination, and Value-Based Payment, Issue Brief (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office, Jan. 2012).

9 R. S. Brown, A. Ghosh, C. Schraeder et al., “Promising Practices in Acute/Primary Care,” In: C. Schraeder and P. Shelton, eds., Comprehensive Care Coordination for Chronically III Adults (New York: Wiley, 2011).

10 C. Boult and G. D. Wieland, “Comprehensive Primary Care for Older Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Nov. 3, 2010 304(17):1936–43.

11 N. McCall, J. Cromwell, and C. Urato, Evaluation of Medicare Care Management for High Cost Beneficiaries (CMHCB) Demonstration: Massachusetts General Hospital and Massachusetts General Physicians Organization, Final Report (Washington, D.C.: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Sept. 2010).

12 R. S. Brown, D. Peikes, G. Peterson et al., “Six Features of Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Programs That Cut Hospital Admissions of High-Risk Patients,” Health Affairs, June 2012 31(6):1156–66.

13 K. J. Verhaegh, J. L. MacNeil-Vroomen, S. Eslami et al., “Transitional Care Interventions Prevent Hospital Readmissions for Adults with Chronic Illnesses,” Health Affairs, Sept. 2014 33(9):1531–39.

14 For example, among PACE programs, higher self-rated interdisciplinary team performance and other program characteristics were associated with better enrollee functional health outcomes. See: D. B. Mukamel, H. Temkin-Greener, R. Delavan et al., “Team Performance and Risk-Adjusted Health Outcomes in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE),” Gerontologist, April 2006 46(2):227–37; and D. B. Mukamel, D. R. Peterson, H. Temkin-Greener et al., “Program Characteristics and Enrollees’ Outcomes in the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE),” Milbank Quarterly, 2007 85(3):499–531.

15 J. E. Mahoney, “Why Multifactorial Fall-Prevention Interventions May Not Work,” Archives of Internal Medicine, July 12, 2010 170:(13)1117–19; and F. Davidoff, “Improvement Interventions Are Social Treatments, Not Pills,” Annals of Internal Medicine, Oct. 7, 2014 161(7):526–27.

16 McCall, Cromwell, and Urato, Evaluation of Medicare Care Management, 2010.

17 C. S. Hong, A. L. Siegel, and T. G. Ferris, Caring for High-Need, High-Cost Patients: What Makes for a Successful Care Management Program? (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Aug. 2014).

18 S. Klein, M. Hostetter, and D. McCarthy, A Vision for Using Digital Health Technologies to Empower Consumers and Transform the U.S. Health Care System (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 2014).

19 T. W. Bickmore, L. M. Pfeifer, D. Byron et al., “Usability of Conversational Agents by Patients with Inadequate Health Literacy: Evidence from Two Clinical Trials,” Journal of Health Communication, 2010 15(Suppl. 2):197–210; and B. Jack and T. Bickmore, “Louise: Saving Lives, Cutting Costs in Health Care” (Boston: Boston University School of Medicine).

20 Several barriers to the adoption of new care models were identified by C. Boult in “Challenges to CaRe-Align,” Presentation to the CaRe-Align Collaboration Meeting, Dallas, Texas, April 23, 2014 (CaRe-Align is an initiative of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the John A. Hartford Foundation).

21 L. J. Damschroder, D. C. Aron, R. E. Keith et al., “Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science,” Implementation Science, Aug. 7, 2009 4:50.

22 A. Wandersman, V. H. Chien, and J. Katz, “Toward an Evidence-Based System for Innovation Support for Implementing Innovations with Quality: Tools, Training, Technical Assistance, and Quality Assurance/Quality Improvement,” American Journal of Community Psychology, Dec. 2012 50(3–4):445–59.

23 R. Brown, “Care Coordination Programs for Improving Outcomes for High-Need Beneficiaries: What’s the Evidence?” Presentation to the Commission on Long-Term Care, July 17, 2013.

24 M. Bihrle-Johnson and D. McCarthy, The Visiting Nurse Service of New York’s Choice Health Plans: Continuous Care Management for Dually Eligible Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Jan. 2013).

25 For example, see: D. O. Meltzer and G. W. Ruhnke, “Redesigning Care for Patients at Increased Hospitalization Risk: The Comprehensive Care Physician Model,” Health Affairs, May 2014 33(5):5770–77.

26 D. McCarthy, S. Klein, and A. Cohen, The Road to Accountable Care: Building Systems for Population Health Management (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, Oct. 2014).

27 For a discussion of capitation rates in Medicare Advantage plans, see: R. Brown and D. R. Mann, Best Bets for Reducing Medicare Costs for Dual Eligible Beneficiaries: Assessing the Evidence (Washington, D.C.: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Oct. 2012).

28 For example, see: A. Hamblin and S. A. Somers, Introduction to Medicaid Care Management Best Practices (Princeton, N.J.: Center for Health Care Strategies, Dec. 2011).

29 For example, see: AcademyHealth, Evidence Roadmap: Integration of Physical and Behavioral Health Services for Medicaid Enrollees (Washington, D.C.: AcademyHealth, May 2015).