Abstract

- Issue: The number of uninsured Americans remains stubbornly high, and many Americans do not obtain the coverage for which they are eligible — even when insurance is free.

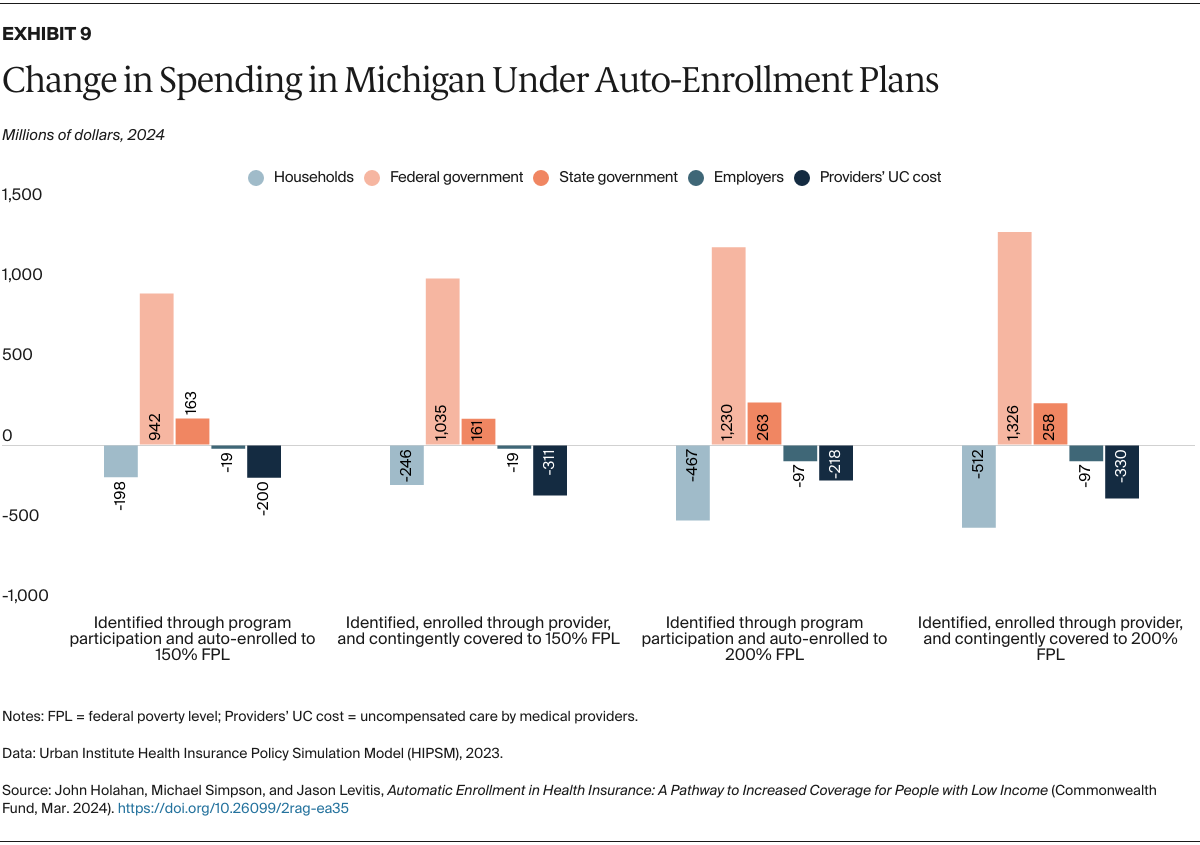

- Goal: To outline a system for automatically enrolling people with low incomes in health coverage and then model the impact on coverage and spending at the federal and state levels.

- Methods: The Urban Institute’s Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model was used to analyze alternative auto-enrollment approaches. These include identifying uninsured individuals who are tax filers or recipients of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), unemployment insurance, or Social Security and enrolling people who are eligible for free coverage.

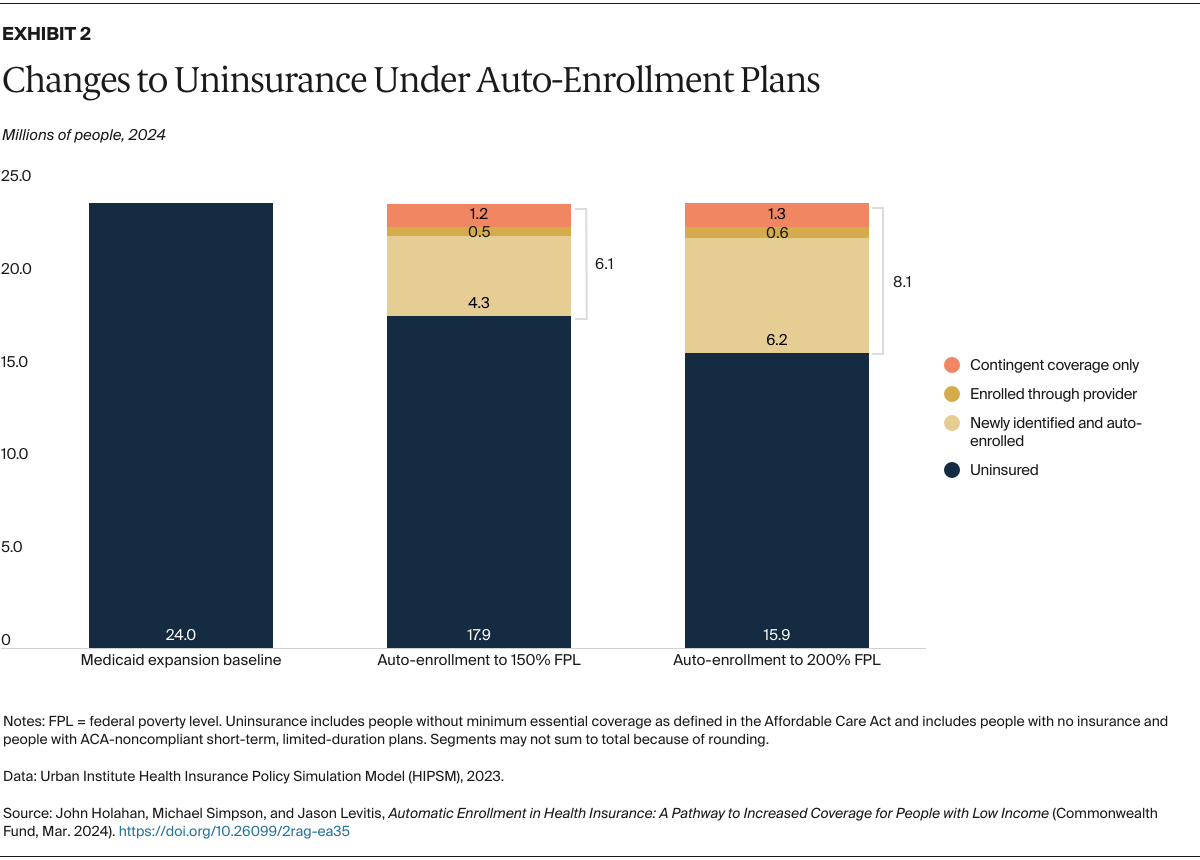

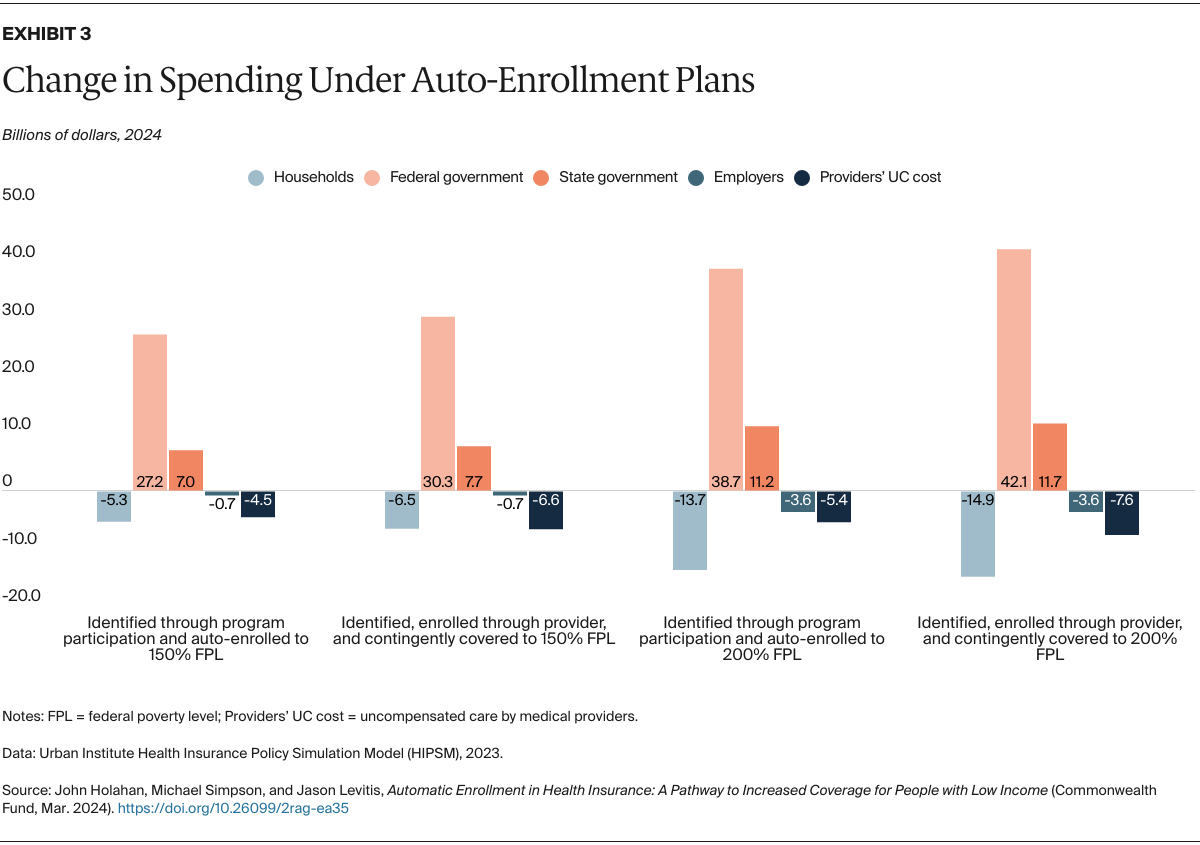

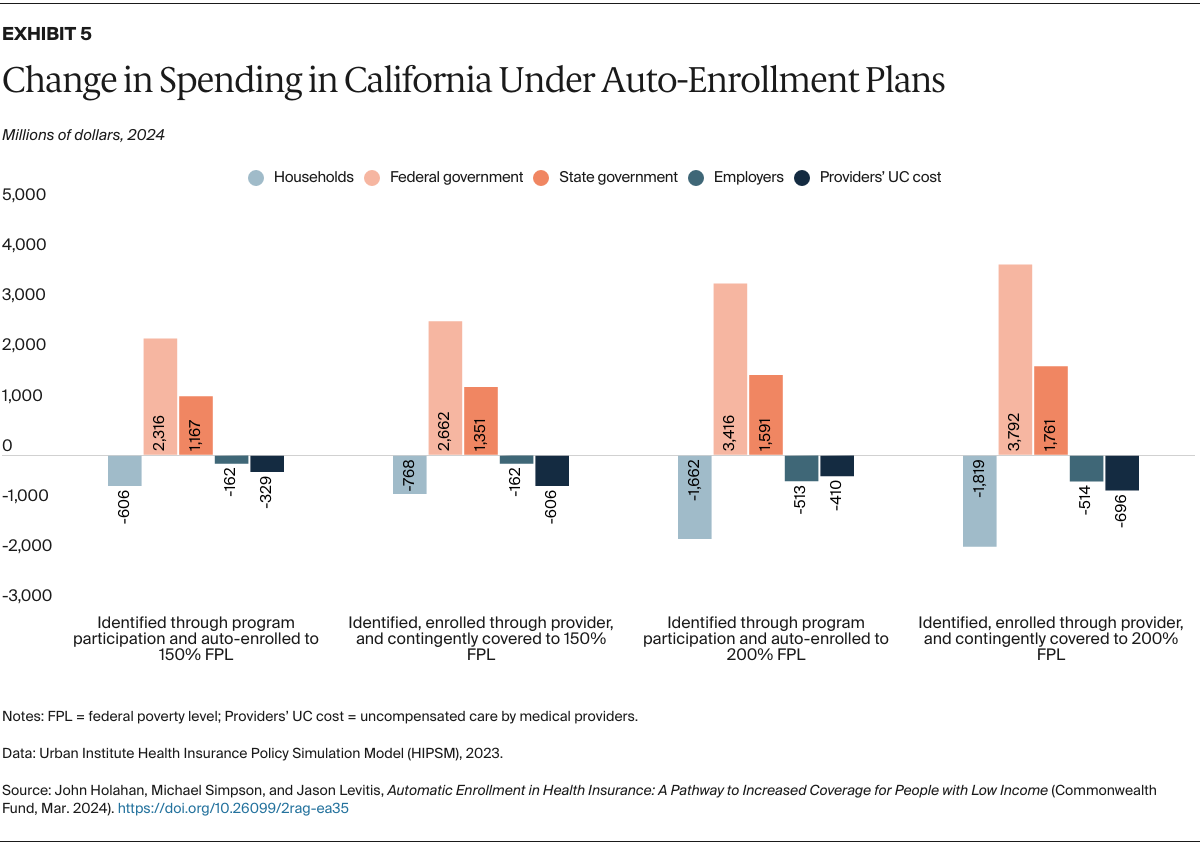

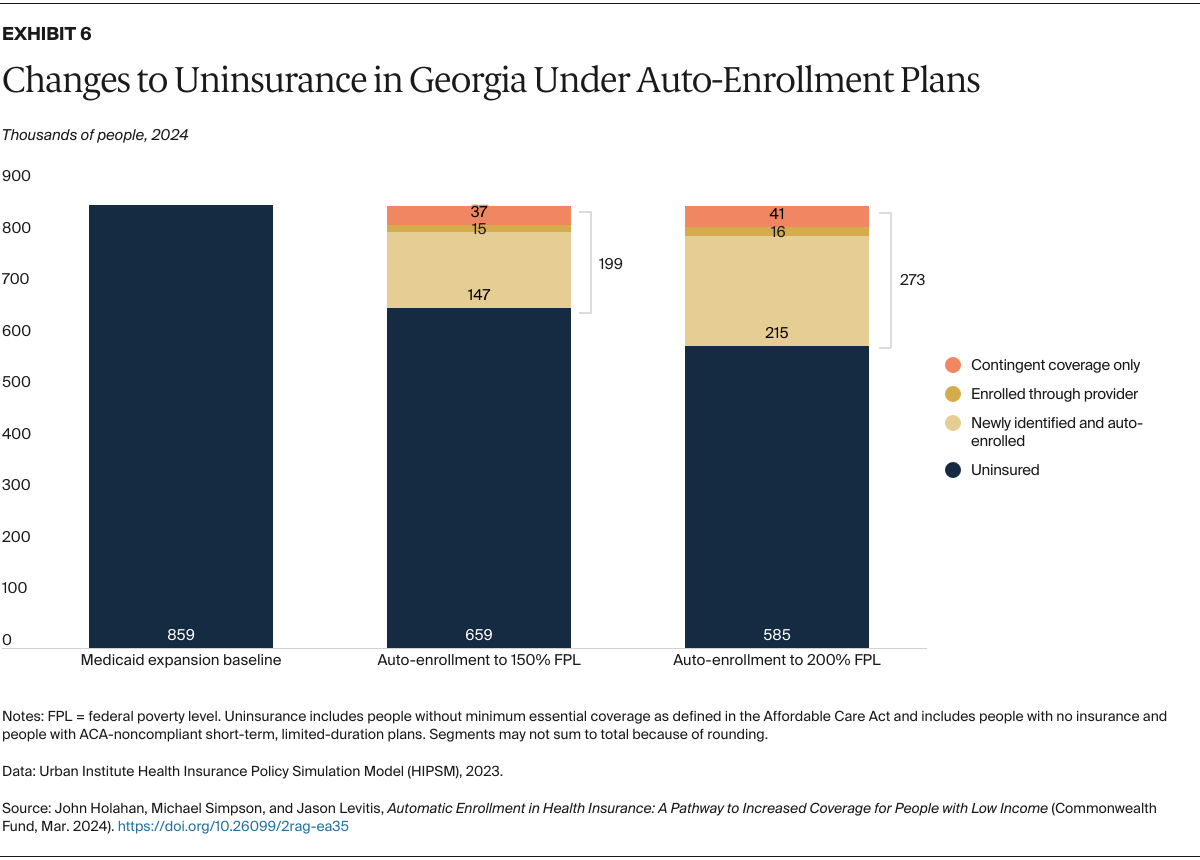

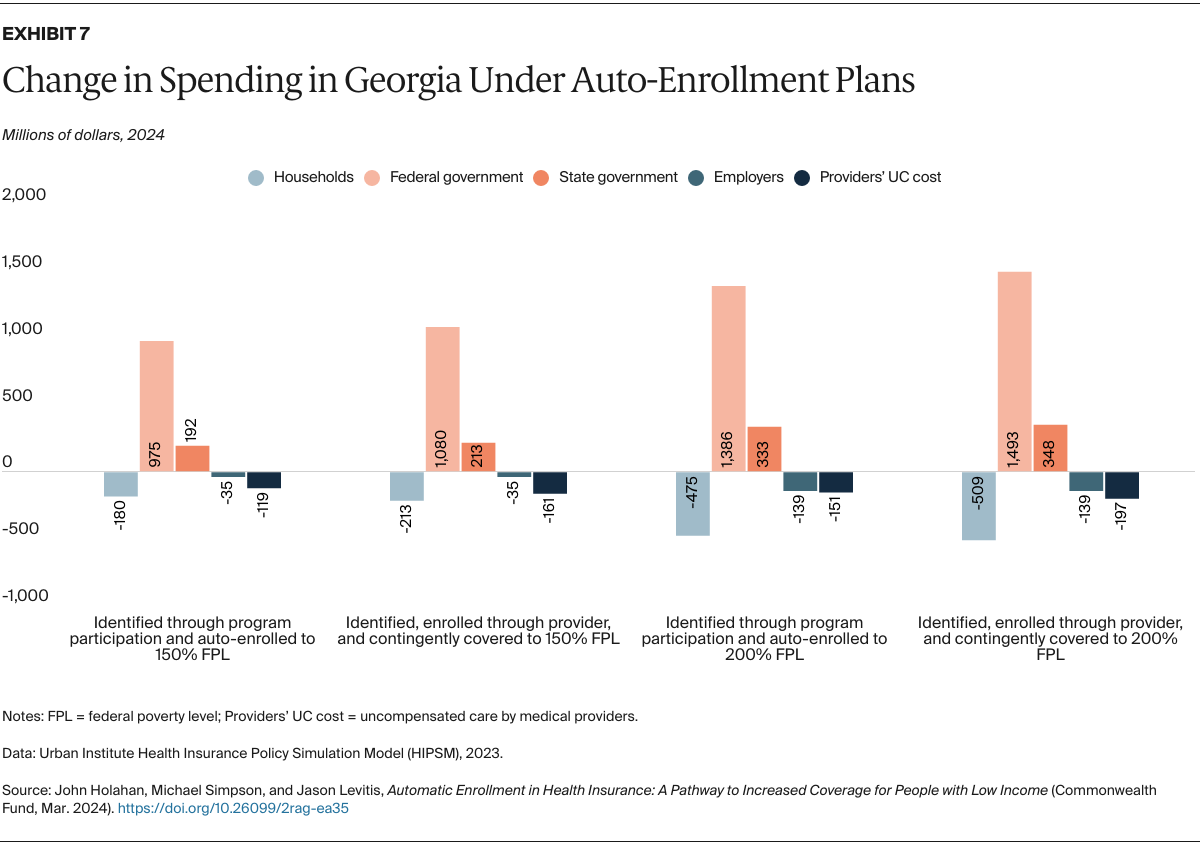

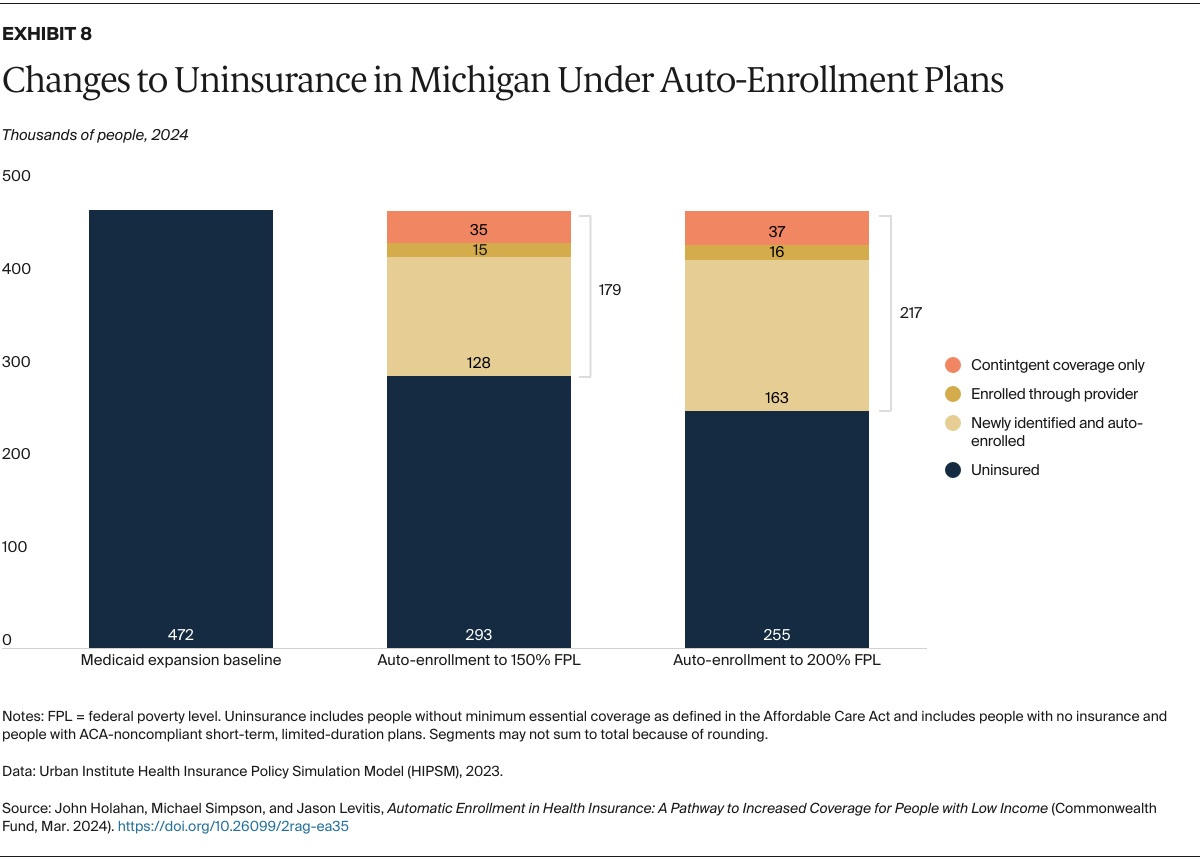

- Key Findings and Conclusions: We show results for the nation and for three states (California, Georgia, and Michigan). If all states adopted an auto-enrollment policy for those with incomes at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty level, 4.3 million uninsured people would be identified and enrolled. An additional 1.8 million would be “deemed” covered, either auto-enrolled through provider contact or contingently covered and thus protected from huge medical bills. Provider spending on uncompensated care would fall 32 percent, while federal spending would increase by $30.3 billion and state spending would increase by $7.7 billion per year.

Introduction

Of the over 26 million uninsured people in the United States, more than half (52%) are eligible for subsidized coverage through Medicaid or the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) marketplaces but do not enroll. Low-income individuals account for a large share of these uninsured. Under current law, people with income below 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) make up 43 percent of the uninsured, and those below 200 percent of FPL make up 56 percent (for a single person in 2024, these income levels translate to $21,870 and $29,160, respectively). Enrolling people who are eligible for zero-premium coverage through Medicaid or the ACA marketplaces could reduce the number of uninsured substantially. In principle, many of these individuals not facing premiums could be auto-enrolled. Auto-enrollment could be enacted nationwide through federal law or by individual states, either with or without federal changes facilitating state action.

In previous work, we looked at the design and impacts of policies that would extend auto-enrollment for the entire U.S. population.1 As a second option, we looked at expanding auto-enrollment to those who participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. Auto-enrollment for the entire population would be a huge and complex policy initiative. In this report, we focus on auto-enrollment only of people eligible for zero-premium coverage through Medicaid or the ACA marketplace. We do not anticipate this proposal would apply to those excluded from program eligibility for immigration reasons, but it could be if eligibility restrictions were eased.

How Auto-Enrollment Might Work

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 eliminated marketplace premiums for eligible people with incomes below 150 percent of FPL. As a result, all individuals at that income level who live in states that have expanded Medicaid can now receive zero-premium coverage, unless they have an “affordable” offer from an employer or are excluded because of immigration status.2 If the remaining 10 states expanded Medicaid, or if eligible people with incomes below 100 percent of FPL in nonexpansion states were permitted to have subsidized coverage in the marketplace, then most legal residents with incomes below 150 percent of FPL could be covered with no premiums.3 Zero-premium coverage could also be extended to higher incomes, either through further enhancement of federal premium tax credits or by states adopting a Basic Health Program or adding state premium subsidies.4

In our model, individuals would be auto-enrolled in Medicaid or the ACA marketplaces depending on their eligibility. A designated administrative agency would identify and enroll individuals after confirming their income and citizenship eligibility using available third-party data. A state’s health insurance marketplace could take on this responsibility since these entities already can determine eligibility for both marketplace coverage and Medicaid. Or a state Medicaid agency or a new agency could oversee this process.

We estimate the impact of two auto-enrollment pathways:

- Enrolling individuals identified as uninsured and eligible for zero-premium coverage based on information from other interactions with government agencies. For this analysis we consider interactions like tax filing and receipt of SNAP, Social Security, and unemployment insurance benefits, which provide key information needed for eligibility determinations and enrollment like name and other identifying data, address and other contact information, family members, and income. Individuals must also typically provide immigration status to qualify for Medicaid and marketplace coverage. The designated administrative agency could verify these eligibility criteria using the Federal Data Services Hub and other third-party data sources. The agency would then confirm coverage status, enroll eligible individuals, and give them an opportunity to opt out or switch plans.

- “Deeming” individuals below designated income levels to be covered even if they did not enroll. If a low-income person went to a hospital or other provider for care, the provider could, following a basic initial screen for immigration and income eligibility, contact the designated administrative agency to enroll the patient, and would then be paid for the services provided. The designated agency would verify eligibility (based on income, citizenship, and other criteria) using third-party data sources like the Federal Data Services Hub and then enroll the patient in Medicaid or a low-cost marketplace plan. Also, at any point in the year, an eligible individual could contact the agency to enroll. Either way, the coverage would reimburse services back to the start of the year, like an enhanced version of Medicaid retroactive coverage. Those who are deemed eligible but do not seek care would be contingently covered and thus protected from the financial risk of uninsurance.

We further expect that auto-enrolled people would be rescreened as their enrollment nears an end and reenrolled if they are still eligible. Individuals could opt out, but this seems unlikely given the lack of premiums. Continuous coverage for a year, which was nationwide Medicaid policy during the COVID-19 public health emergency and continues in some states, could be one possible option.

Policy Considerations for Auto-Enrollment

Successful auto-enrollment would require implementation of at least five policies:

- Lowering the employer coverage firewall. Under the ACA, people with an offer of employer coverage deemed “affordable” are ineligible for marketplace subsidies (but not for Medicaid). These individuals lack access to zero-premium plans, so auto-enrollment would not apply to them. As a remedy, the firewall could be waived for workers with incomes low enough to qualify for zero-premium coverage.

- Creating an aggressive, ongoing, and well-funded education and enrollment assistance campaign. The policy would need to create awareness that all individuals below 150 percent (or 200 percent) of FPL are effectively insured through Medicaid or marketplace plans, and that even those who did not actively choose a plan are covered. A major administrative effort would be needed to enroll individuals, either those who seek active enrollment or those who are referred by a provider.

- Eliminating the clawback of advance premium tax credits for the population provided free coverage. Currently, recipients must agree to receive those credits in advance and to reconcile them when they file their income taxes. Reconciliation could be waived for auto-enrollees and others who are eligible based on their incomes.

- Offering a special enrollment rule for marketplace coverage. Marketplace enrollment is normally permitted only during the year-end open enrollment period and designated special enrollment periods for circumstances like loss of coverage or new eligibility for subsidies. A special enrollment rule could be established to allow people who are eligible based on their income to enroll in a plan at any time.

- If auto-enrollment were to be adopted nationwide, the Medicaid gap in nonexpansion states would need to be filled by expanding Medicaid or by providing zero-premium marketplace coverage. Currently, adults with incomes below 100 percent of FPL are largely ineligible for subsidized health care in the 10 nonexpansion states, so auto-enrollment in those states would not benefit many people without this change.

These policies could be enacted nationwide through federal law or by individual states, either with or without federal changes facilitating state action. (See box, “Federal and State Legislative Approaches to Auto-Enrollment,” for a discussion of these options.)

The availability of a public option (a government-sponsored plan intended to increase competition in the marketplace) would also make auto-enrollment easier, though it is not necessary, and we do not assume one here. Such a plan could potentially charge premiums below those of other insurers, which would lower the costs of the proposal. It could act as the default plan for auto-enrollees who are not eligible for Medicaid. Without a public option, individuals in the marketplace would have to be enrolled into one of the lowest-cost marketplace plans. There would be issues related to assignment of individuals to plans, plan capacity to serve additional enrollees, and adequacy of plans’ provider networks. These issues are solvable but could be avoided with a public option in place.

The Potential of Auto-Enrollment to Offset Costs

An auto-enrollment policy has the potential to improve the average health risk and reduce the average premium in the marketplace by bringing in people with low demand for health care services, compared to existing enrollees. By auto-enrolling people who did not sign up for coverage on their own, average costs and premiums could fall. Some of these individuals have no medical spending in a given year. For example, in 2021 more than 15 percent of the nonelderly population had no medical spending.5 By auto-enrolling at least some of these individuals, their low costs to the system could offset some of the costs of existing enrollees.

We anticipate that the number of people not actively enrolling in insurance coverage would decrease over time. Many people who are directly enrolled after use of services would actively reenroll. Personal experience, education campaigns, and knowledge disseminated through news outlets and social contacts would teach people the advantages of active early enrollment to receive no-cost coverage. These efforts could encourage individuals who would have to pay premiums to enroll as well, and fewer people might delay enrollment over time.

Four Options for Auto-Enrollment

We modeled four reform options that build off the Medicaid expansion baseline, including estimates for the 10 nonexpansion states, assuming they would expand before initiating auto-enrollment (see Appendix 1 for coverage and spending effects for those states).6 For all the options, we assume the firewall and advance premium tax credit reconciliation would be eliminated for everyone in the auto-enrollment income range, that a special enrollment rule would be provided for the same group, and a robust outreach campaign would be in place. We present national results under the assumption that all states adopt auto-enrollment and highlight results for selected states, as this policy could be an option for states seeking to reduce uninsurance. The four reform options are:

- Auto-enroll eligible uninsured people with incomes below 150 percent of FPL if they are identified through tax filings or receipt of SNAP, Social Security, or unemployment insurance benefits. This group would have zero-premium coverage, and the employer coverage firewall would be removed for people with incomes below 150 percent of FPL.

- Same as option 1 but deem all people with incomes below 150 percent of FPL and who are eligible for zero-premium coverage as insured even if they are not identified through program participation and auto-enrolled. Thus, when an individual visits a provider for services, the provider would receive payment if they refer the patient to the designated agency for enrollment. Any services received earlier in the year also would be paid. Other eligible individuals would be financially protected even if they have not actively enrolled.

- Extend zero-premium coverage to 200 percent of FPL. As in option 1, people identified through tax filings or program participation would be auto-enrolled, and the employer coverage firewall would be removed below 200 percent of FPL.

- Same as option 3 but deem all people with incomes below 200 percent of FPL and who are eligible for zero-premium coverage as insured even if they are not identified through program participation and auto-enrolled.

Details on data used and modeling methods are presented in Appendix 2.

Eligibility for Subsidies and Auto-Enrollment

Before gauging the effects of various auto-enrollment policies, we first estimated how expanding Medicaid in every state and eliminating the employer coverage firewall would affect the number of uninsured people eligible for free coverage. With Medicaid expanded in every state, 13.4 million uninsured people would be eligible for Medicaid or ACA subsidies (Appendix Table 3.1). Of these:

- 6.0 million have incomes below 150 percent of FPL and are eligible for coverage with no premiums

- 1.3 million more have incomes between 150 percent and 200 percent of FPL and would be eligible for zero-premium coverage under reform options 3 and 4

- 6.2 million have incomes above 200 percent of FPL, so would not be eligible for zero-premium coverage or auto-enrollment under these reforms.

Eliminating the employer coverage firewall would enable 1.2 million people with incomes below 150 percent of FPL and 6.5 million people with income between 150 percent and 200 percent of FPL to become newly eligible for subsidies (Appendix Table 3.2). Most people who would gain eligibility are currently covered by employer-sponsored insurance (ESI), but some currently pay full premium for nongroup coverage, and 1.1 million are currently uninsured and could be auto-enrolled under reform. In addition, some of the 6.4 million people covered by ESI who would gain subsidy eligibility under reform options 3 and 4 would likely drop ESI for zero-premium coverage.

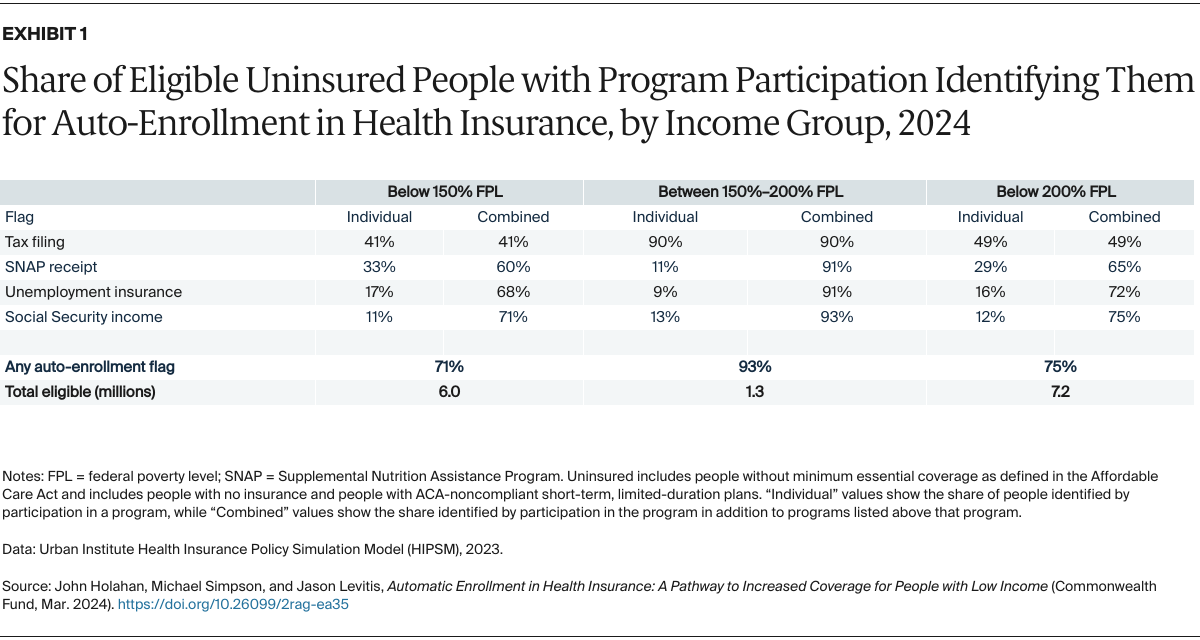

Tax filing or government program participation could help identify the eligible uninsured. Below 150 percent, tax filing reaches 41 percent of the uninsured, and other programs extend the reach to 71 percent. Tax filing reaches 90 percent of the uninsured with incomes between 150 percent and 200 percent of FPL; other programs bring the total reached to 93 percent for that group (Exhibit 1).