The growing debate over economic inequality in the developed world, highlighted by Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, raises an interesting question that is particularly pertinent to the United States. Have escalating health care costs contributed to the huge economic gap between America’s rich and the rest? The evidence, it turns out, is suggestive, but not definitive.

From the perspective of the more than 150 million Americans who receive health insurance through their employers, health care costs may, in fact, be widening inequality. Economists generally agree that employers for the most part treat workers’ compensation in all forms—wages and benefits—as a single expense. When health insurance premiums go up, employers may reduce take-home pay to keep overall compensation in check.

Because health costs have grown so quickly over the past several decades, an increasing share of workers’ total compensation has gone toward health insurance premiums. These higher premiums partly explain why middle-class wages have stagnated, lagging productivity gains. Rising health care spending—both on premiums and out-of-pocket costs—totally erased wage gains for a typical family from 1999 to 2009.

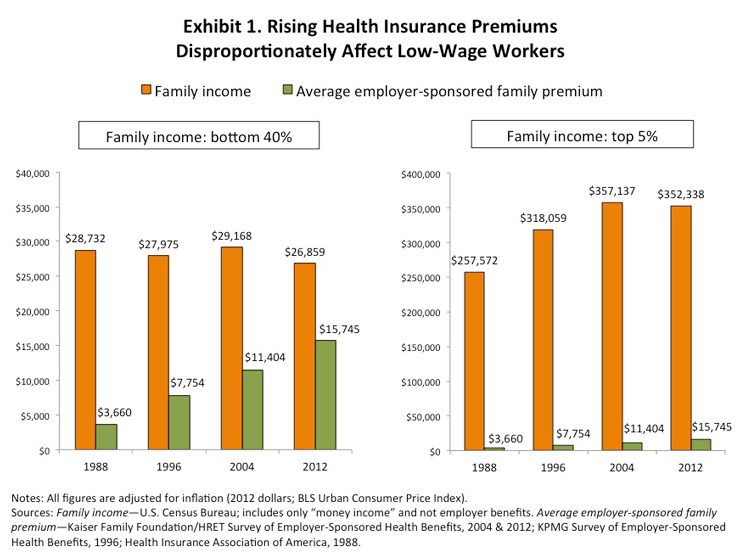

To illustrate, Exhibit 1 compares health insurance premiums relative to income for U.S. families in the bottom 40 percent of the nation’s income distribution versus the top 5 percent. From 1988 to 2012, the average employer-sponsored insurance premium rose from $3,660 to $15,745. For families in the lower-income bracket, that represents an increase from 13 percent to 60 percent of average annual income. For those in the upper-income bracket, premium increases amounted only to a rise from 1.4 percent to 4.5 percent of income—a much smaller drain on workers’ take-home pay.

Still, there are important nuances. The insurance coverage provided through employer-sponsored plans may have disproportionate value for lower-income workers. If they use more health care than their better-paid coworkers, they may gain more economic benefit from their health insurance. This could be the case for the many lower-income Americans in poor health.

However, rising deductibles and copayments have reduced the value of health insurance over time, and these out-of-pocket costs weigh more heavily on low-income workers. Also, the added benefits may not be worth the disproportionate economic burden imposed on lower-income employees. The Institute of Medicine estimates that about 30 percent of health care expenditures are wasteful. For lower-income workers, wasting 30 percent of what they pay for health care is a far greater burden than it is for higher-income employees. In other words, if the health care system were more efficient and less costly, lower-income workers might gain considerably more—as a proportion of total compensation—than higher-income workers.

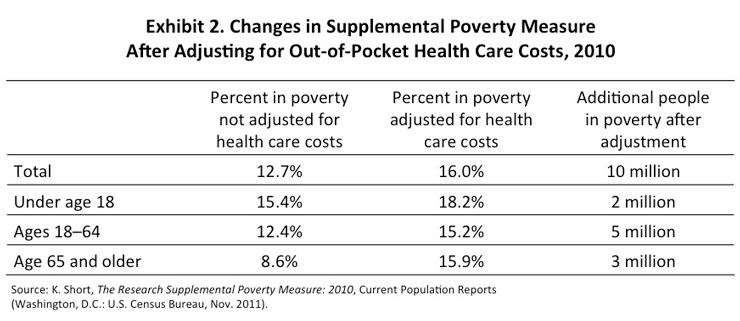

Other evidence of the inequality-increasing effects of high health care costs emerges in a 2011 blog post by The Commonwealth Fund’s Sara Collins. According to a then-new Census Bureau measure, the national poverty rate increased by 3.3 percentage points, or by about 10 million people, when family incomes were adjusted for out-of-pocket medical costs (Exhibit 2). In other words, health care costs may be directly increasing the number of Americans living in poverty. This is consistent with the observation that health care–related expenses contribute to more than half of personal bankruptcies in the United States. Most of these medical debtors worked in middle-class occupations and had health insurance.

The story, however, does not end here. As health care costs rise, the amount of money effectively transferred to low-income Americans through public health care programs like Medicaid and Medicare increases as well, reducing social inequality. Two-thirds of Medicare funds and 83 percent of Medicaid funds are spent on care for the poorest 40 percent of the population.

The many reforms included in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) also reduce inequality, largely by expanding Medicaid and subsidizing low- and moderate-income Americans’ purchase of health insurance in the marketplaces. Furthermore, the marketplace subsidies address the historical inequity between workers offered insurance through their employer (thereby benefiting from the generous tax exemption for such plans), and those forced to shop for coverage on their own. Low- and moderate-income workers are far more likely to fall into the latter group, and so were disadvantaged—economically and medically—prior to the ACA.

To complicate matters even further, the impact of health spending on inequality is felt on two ends—who pays, and who gets paid. The lion’s share of health care expenses translates into health care workers’ income. A full accounting would need to compare the distribution of health care workers’ earnings to that of the rest of the population. And while physicians are listed as one of the most common professions among those in the top 1 percent of income, nursing and other clinical roles generally offer some of the most reliable middle-class wages in America today.

There is much more that could be said about this topic. A definitive answer would probably require an analytic exercise worthy of Piketty’s 700-page treatise. But even this brief consideration of the relationship between health spending growth and widening inequality leads to one underappreciated conclusion: In America today, all macroeconomists are to some degree health economists, and vice versa. And understanding the relationship between these seemingly inexorable trends would likely prove fruitful for economists of both stripes.